People have to pay $9 to enter Manhattan below 60th Street. What happened so far?

We’ve now had over a week of congestion pricing in New York City.

It took a while to finally get it.

The market for whether congestion pricing would happen in 2024 got as high as 87% before Governor Hochul first betrayed us. Fortunately for us, she partially caved. We finally got congestion pricing at the start of 2025.

In the end, we got a discount price of $9 in Manhattan south of 60th Street, and it only applies to those who cross the boundary into or out of the zone, but yes we finally did it. It will increase to $12 in 2028 and $15 in 2031.

As part of this push, there was an existing congestion surcharge of $2.50 for taxis and $2.75 for rideshares. Thus, ‘congestion pricing’ was already partially implemented, and doubtless already having some positive effect on traffic.

For rides that start or end within the zone, they’re adding a new charge of $0.75 more for taxis, and $1.50 more for rideshares, so an Uber will now cost an extra $4.25 for each ride, almost the full $9 if you enter and then leave the zone.

Going in, I shared an attitude, roughly like these good folks:

Sherkhan: All big cities should charge congestion fees and remove curbside parking. If people viewed cities like they viewed malls, they’d understand it would be ridiculous to park their car in the food court next to the Sbarro’s Pizza.

LoneStarTallBoi (Reddit): As someone who routinely drives box trucks into the congestion zone, let me just say that this makes zero difference for my customers, the impact on my bottom line is next to nothing, and I don’t care if every dollar collected goes to build a solid gold statue of Hochul, as long as there are a few less of you deranged, mouth breathing, soft handed idiots on the road. Take the fucking bus, take the fucking train.

Well said.

Like any other new policy, the first question is how to enforce it.

The answer is, we can all pay via E-ZPass, and if you try to go into the zone without one, we take a picture of your license plate.

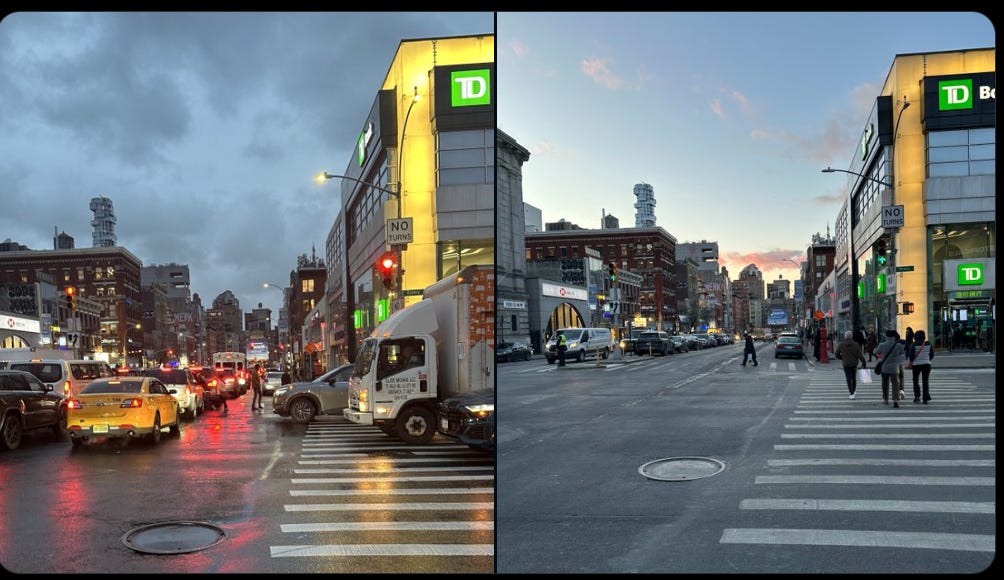

Everyone agrees it is dramatically improving on the tunnels and bridges.

Sam: this is INCREDIBLE, congestion pricing is already working wonders

traffic at 1: 30PM on the average Sunday vs today

Holland Tunnel: 27 mins ➡️ 9 mins

Lincoln Tunnel: 10 mins ➡️ 3 mins

Williamsburg Bridge: 11 mins ➡️ 6 mins

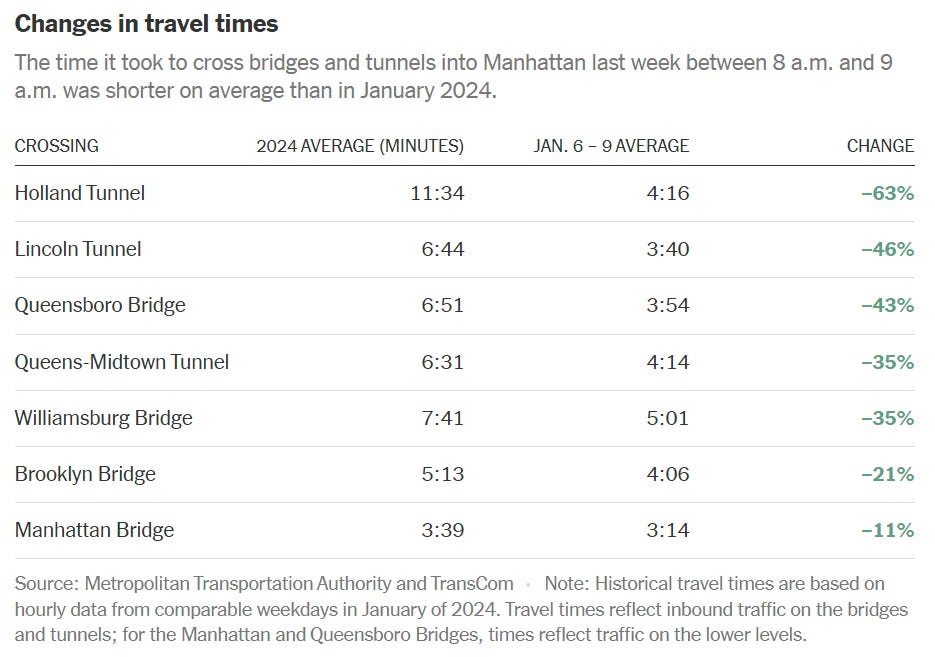

The New York Times reported this from the MTA and TransCom:

At actual zero traffic these would each take between 2 and 3 minutes to cross, so this is a 50%+ reduction in extra time due to traffic. And it is a vast underestimate of the total time saved, because when we talk about for example ‘delays at the Holland Tunnel’ most of it comes before you reach the tunnel itself.

If you want to look yourself, here is the congestion pricing tracker.

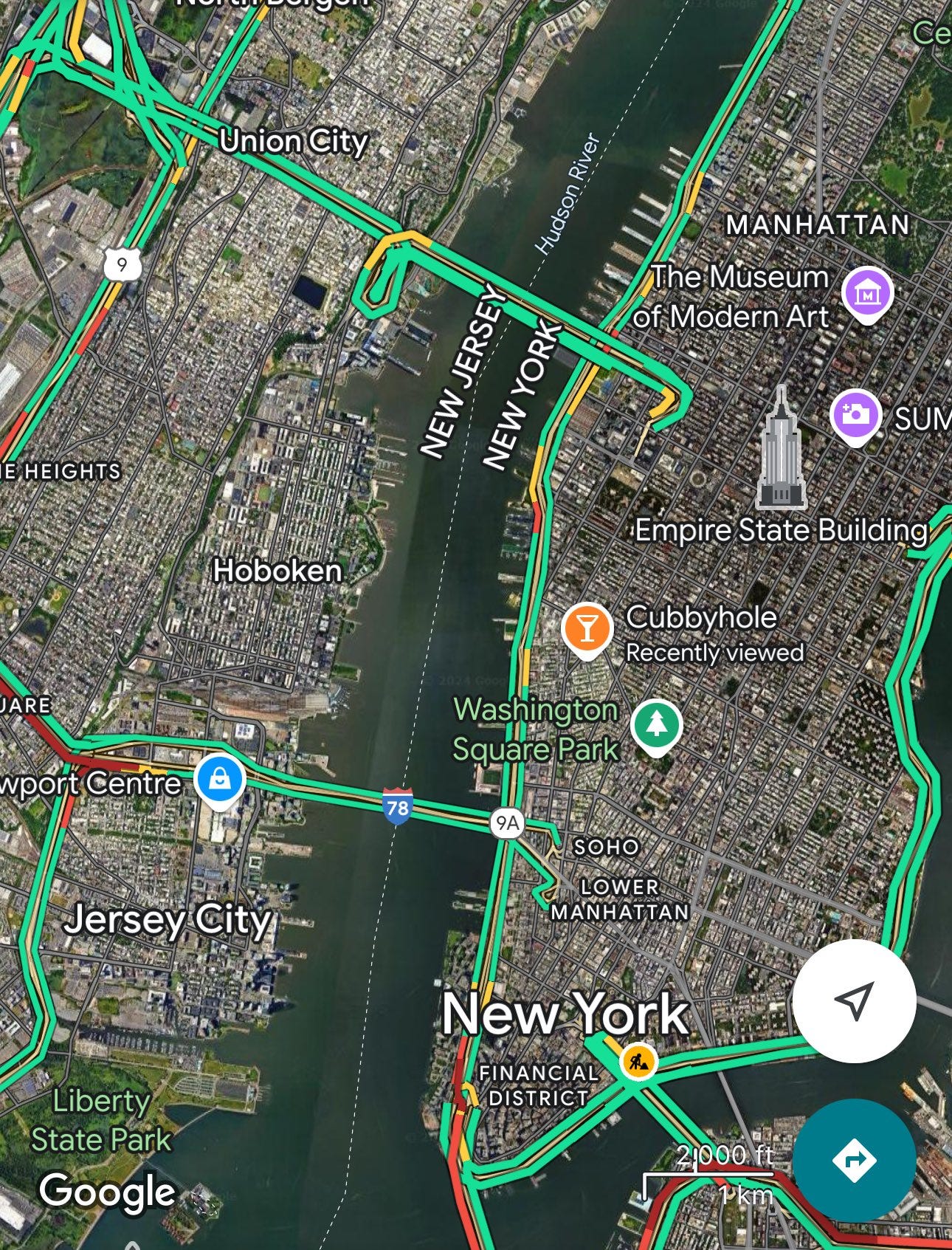

Cremieux: Congestion pricing is amazing.

The roads are clear, the trains aren’t overloaded, and “rush hour” now feels like it’s just a bad policy choice.

Jule Strainman: I was told by a guy who spent $20 on a cookie that NYC would implode with Congestion Pricing? Well it’s Monday morning and the tunnels are CLEAR!

Steven Godofsky: it’s hilarious how high the elasticity is here, my goodness

Jule: Everyone calling me slurs told me yesterday was a snow day/Monday/holiday and didn’t count…now what!

Unpopular Polls shows the roads from outside the zone being crowded.

Jule: So we should extend the congestion zone to uptown and Brooklyn? I agree!

I agree as well, at relatively lower prices of course.

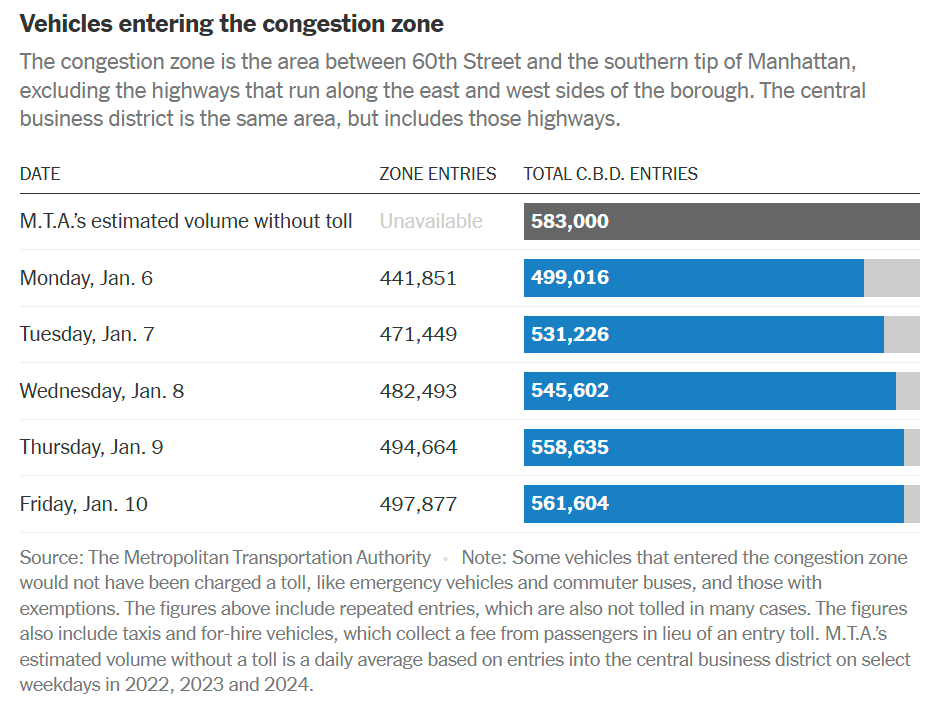

The MTA records a modest reduction in entries into the zone. When we look in absolute numbers, the elasticity looks reasonable – a $9 charge reduced total throughput by ~7.5% (although this doesn’t adjust for the low temperatures), or 43,800 fewer vehicles per day, but that marginal 7.5% can make a huge difference by shifting traffic to a new equilibrium.

Ana Ley, Winnie Hu and Keith Collins (New York Times): “There’s so much evidence that people are experiencing a much less traffic-congested environment,” said Janno Lieber, the chairman and chief executive of the M.T.A., which is overseeing the program. “They’re seeing streets that are moving more efficiently, and they’re hearing less noise, and they’re feeling a less tense environment around tunnels and bridges.”

…

Traffic improved along some streets within the congestion zone, but remained snarled in other areas like the length of West 42nd Street and Ninth Avenue between West 60th and 14th Streets.

…

Of the 1.5 million people who work in the tolling zone, about 85 percent take mass transit, according to the M.T.A. Only 11 percent drive — about 143,000 drivers before congestion pricing was implemented.

Within the city, there are three positions one can take.

-

Traffic is not improving within the city.

-

Traffic is improving within the city, and that’s awesome.

-

Traffic is improving within the city, and that’s… terrible?

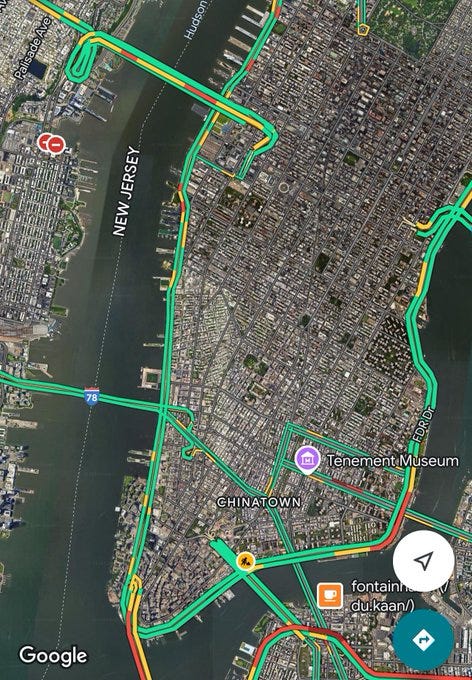

Position number one is certainly possible in theory. The data on the congestion pricing tracker, which Gupta and others refer to, indeed suggests that routs internal to the zone are unchanged.

There are reports claiming that trips that cross into the congestion zone are improved a lot, but within the zone many claim things aren’t changing much.

For example here is a report from Michael Ostrovsky, who thinks this is because the majority of traffic within the zone is taxis and TLCs, which were not much impacted, the surcharge change was not so large and people likely didn’t even realize it yet.

Michael Ostrovsky: Both videos are from Dec 7. First one is from Holland Tunnel exit. Over the 10 minutes, the video shows 179 regular cars, 93 TLCs, and 7 taxis (plus a bunch of cars without front plates – but that’s a separate issue). So – a substantial majority of vehicles are regular cars.

The second video is from an intersection within the congestion pricing zone (8th Avenue and 30th Street). Over the similar 10-minute period, the fractions of different types of vehicles are completely different: only 48 regular cars, vs. 60 TLCs and 50 taxis.

Arpit Gupta: Large improvements in morning rush hour commute times into Manhattan as well.

However, travel times *withinthe decongestion zone are not affected. It could be much of this traffic was by residents within the zone anyway, who don’t pay additional costs.

Lower congestion as well for the Williamsburg bridge; maybe the Queens-Midtown tunnel; and the Queensboro bridge.

Also mild evidence of displacement of traffic onto FDR and the Hugh Carey tunnel.

This is also the Tyler Cowen position, it is remarkable how much his reaction attempts to convey negative vibes to what, by his own description, is clearly a positive change – such as warning that if traffic improves, people inside Manhattan might respond with more trips, although this would reflect gains, and also they are highly unlikely to use their own cars for such trips and taxi fees have risen. I appreciated the note that long term adjustment effects tend to be larger than short term, and not to jump to conclusions.

As both Ostrovsky and Cowen note, the correct answer is to charge the fee for cars on the street within the zone, and to raise the fees on taxis to at least match the fees for visitors – although I expect that 50% of the baseline fee for taxi trips within the zone is good enough for equality, because a visitor makes a trip there and then a trip out, or better yet I like the extra per-mile charge as per Ostrovsky, so we don’t overly penalize short trips. And I like that Cowen refers to ‘stiff’ tools – we want enough fees to actually cause people to drive and take taxis less, enough to improve traffic. It does seem like we’ve at least done that with the bridges and tunnels, even at $9.

I suspect the congestion tracker isn’t picking up the full situation. Too many others are making observations that suggest the situation is very much otherwise, with greatly reduced traffic. Even if this is due to weather, the tracker should be picking that up, so it’s strange that it isn’t. I’m not sure what to make of that.

Anecdotally, most people on the ground think traffic is lighter.

This could be biased by it being early January, when traffic typically dies down a bit, and an unusually cold one at that. This is still an overwhelming vote with 90%+ reporting improvement.

Sam Biederman: Congestion pricing is amazing. Was just in Lower Manhattan. Not car-choked, foot, bike and car traffic flowing very freely. Good idea, absolutely worth $9.

You haven’t lived until you’ve parked your Winnebago on Spring St.

One would think that, if one were under that impression, this would result in position number two. Often it does.

Now, dear readers, allow me to introduce advocates of position number three!

NYC Bike Lanes: Before & after congestion relief toll. Congestion pricing works!

Yiatin Chu: Unless swarms of ppl are coming out of subway stations, biking in 20 degree weather or even taking Ubers, congestion pricing is killing Chinatown.

Al: Allow me to share what I’ve seen in NYC one week after the congestion tax began:

– a consistent ~65% decrease in cars

– a consistent ~35% – 50% less people

Everywhere.

You will see the pro-tax people celebrating nothing changing. Their posts boast about all the people. What they don’t tell you, because you may not know, is while there are people, there are soooo many fewer people.

I cycled down 5th Avenue from the 70s to downtown around 2: 30pm today, Saturday, past the shopping and Rockefeller areas — a ridiculously low number of people compared to usual.

In Washington square park now, while there are people, there are far fewer people. It’s midday on a not frigid Saturday. This is abnormal.

As soon as one leaves Times Square, the volume of people dies down to far less numbers as well. I walked into several businesses to ask how this week was and I received eye rolls followed by “don’t even ask.”

In trying to please the a small group of progressives, the city has begun the process of uprooting that which has made a home here.

@GovKathyHochul @NYCMayor you have both failed us miserably.

Drops like that are very obviously some combination of ‘people are able to actually get where they are going faster’ and ‘it was really fing cold.’

If they are real. They quite obviously aren’t real. Measured cars coming into the city are down less than 10%. No, a $9 charge did not cause sudden mass abandonment of downtown Manhattan, where many pay $100+ per day in extra rent to live there.

Then remember the subway and bus ride counts earlier, and a lot of people walk. Yeah, this was obviously about it being below freezing outside.

The threads above were examples of some very angry people. A lot of threads about this were like that. The amount of vitriol and hatred that many on Twitter are directing at anyone supportive of congestion pricing is something else.

We also have a remarkable amount of ‘NYC is dying and that is a good thing.’

And a lot of ‘you got rid of poor people, congratulations (you monsters).’

And my personal favorite, it isn’t the same without all the cars?

Joomi Kim: Part of the appeal of Chinatown is how crowded and chaotic it feels. Not just with pedestrians, but cars.

The people who don’t like this really, really don’t like this. I’ve seen some nastiness around AI and of course around politics, but somehow this is the worst I’ve seen it. Some of it is accusations of hating or driving out poor people, some of it claims the city is dying (or that it’s good the city is dying). It’s like a 2020-style cancellation mob is trying to form, except it’s 2025 and about congestion pricing, so no one feels the need to care.

Then there are the people who felt like this before, and then turn around when they see the results and realize, oh, this is actually great.

The purpose of congestion pricing is in part to switch people from cars to trains.

Which in turn means, by default, more crowded trains.

Joe Weisenthal (January 8): I can’t remember the last time the NYC subway felt this packed. Really annoying. Just basically every ride since Sunday.

Anecdotally I found the same, the trains did seem more crowded than usual.

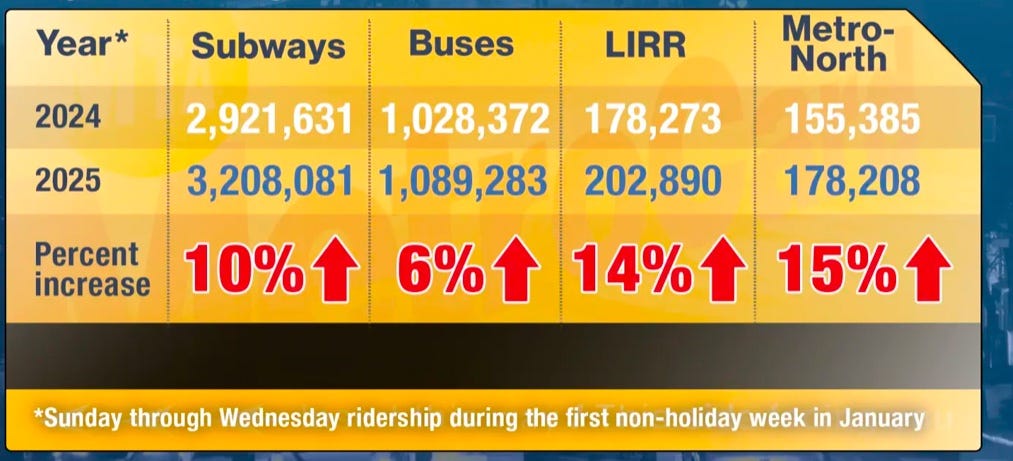

How much more crowded?

It can’t be that much, because trains are a lot more efficient than cars.

Gary Basin: How could the trains not be overloaded 🤔

Big Pedestrian: Swarms of people come out of New York City’s subways every day. The subway carries 3.6 million people a day and buses carry another 1.4 million. There are only ~100K daily drivers into Manhattan.

Cars are giant, expensive space hogs.

The New York Times reports the MTA has it at ~143k workers driving in per day.

Peter Moskos: I hope this lasts. The reasons roads can have less traffic and subways not get much more crowded is because roads are so inefficient. The Queensboro Bridge carries 142,000 vehicles/day. At rush hour, the N/R/W subway under it runs 54 trains, with a capacity of 54,000 people/hour!

The N/R/W isn’t even a relatively good train, it’s relatively slow, someone get on that.

A majority of those ~150k daily drivers will presumably pay the $9, only some of them will substitute into the subway or a bus, and some people will increase their trip counts because of the time saved. Total throughput on the bridges and tunnels is down less than 10%.

So this doesn’t seem like it should be able to increase ridership directly by that much, plausibly this is capped at ~2% of ridership, it certainly can’t be 10%+.

So yes mass transit use is up year over year, but it mostly isn’t due to this.

That is enough to cause noticeable marginal trouble at rush hour on some lines that were already near capacity, especially the green line (4-5-6) which I was on most often, but you could fix it entirely by running more trains.

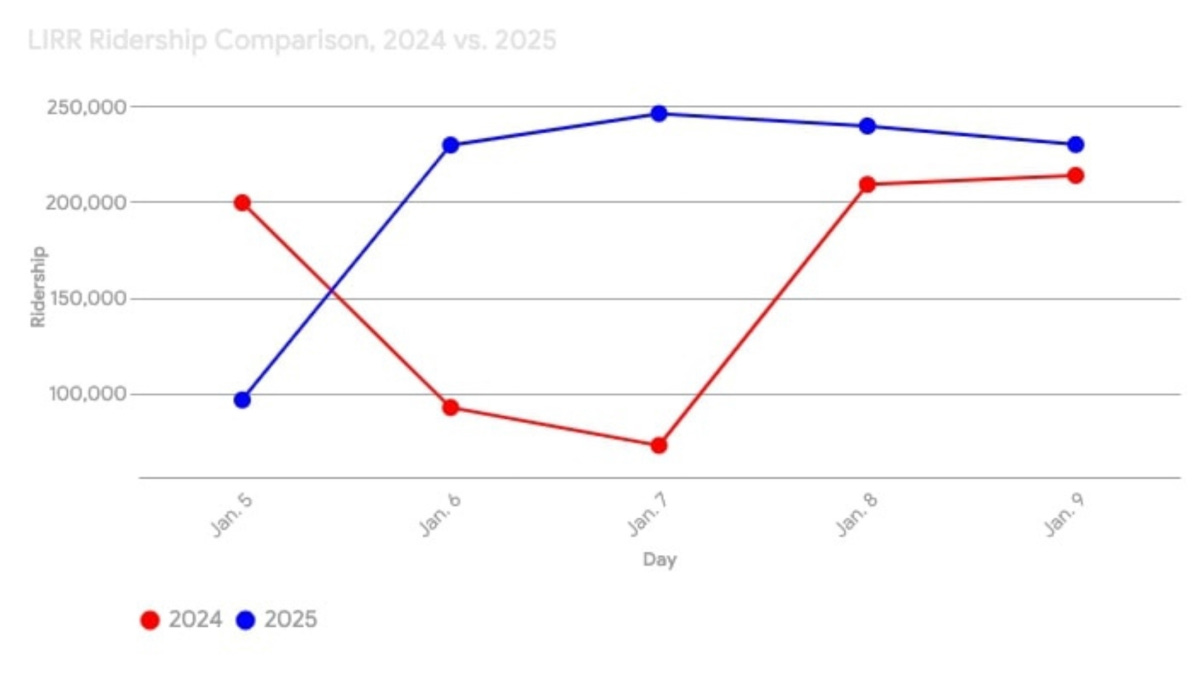

LIRR and MetroNorth have seen 14% and 15% ridership increases in the first week compared to last year, but some of that was baked in and I’m expecting the medium-term impact from this to be much lower, although capacity on those lines is a lot lower than the subway so a substantial increase is more plausible (graph source: NYS Open Data).

There is an obvious easy solution there, of course, which is to add more trains, especially at peak times. The same is true of the subway.

If ridership goes up, and you add more trains such that average ridership per train stays the same, everyone is better off, with shorter wait times, and the system is more profitable to boot. That can be an issue if you run out of capacity, but that’s not a physical issue anywhere but maybe the 4-5-6. So at worst this is a short term problem.

The Big Pedestrian side of this is obviously right, if there is indeed an impact.

Peter Lavingna: Manhattanites are 100% dependent on trucks for all their food and goods. You’re aware of this, right?

Big Pedestrian: There are very few things that are zero-sum, but driving in cities is one of them. If you are a truck driver delivering goods, then a policy which charges ~$14 but saves hours of delivery time is a very good value. The time of the delivery driver is worth more than the charge.

Sam: It turns out congestion pricing is actually quite good for many businesses because saving hours of wasted labor and gas stuck in traffic is far more valuable than the $9 charge.

Nate Shweber: Andrei Biriukov, an elevator mechanic, raved about the lack of traffic on Monday. “Today is amazing,” said Biriukov, 38, a Staten Island resident originally from Ukraine. He said he could cruise to jobs, arrive early and find parking right out front – and the roads felt “not dangerous.” He conceded that his employer pays the tools; he believes the company will recoup the value in more prompt service and happier employees.

The legal minimum wage in New York City is $16.50, even entry level service jobs requiring no starting skills mostly pay $20+/hour, babysitters realistically cost $30/hour, and the median salary in Manhattan is $173k/year or $86/hour at full time, within the zone the median is even higher and cost of employment is substantially higher still. The break-even point for congestion pricing, where the employer pays the cost, is super low if there are any traffic benefits whatsoever.

The weird part about all this is that $9 is so little money.

The price of living in the congestion zone is very high. If you want a one bedroom apartment you can expect to pay over $4,000 a month, or over $130 a day, several times the national average.

Or consider the price of parking in the zone. Typically, monthly parking spots are on the order of $600. Daily rates are on the order of $50. Even metered parking is $5.50 for one hour, $9 for two.

So it would be very easy for other costs to offset the $9 here.

Matthew Yglesias: Something to watch out for is that if fewer people are driving into Manhattan that should reduce parking prices such that the all-in cost of driving falls back to its prior level and the congestion returns — need to be prepared to raise the fee if needed.

Svenesonn: I’m sure parking spaces will be repurposed for better more profitable stuff.

Matthew Yglesias: Yes but that’s good!

A shift to where less land is used for parking, where there are lower levels of traffic congestion, and where congestion fees can substitute for taxes on labor & investment should be the goal for all cities.

Whether or not this then raises the necessary congestion price is unclear.

The whole situation is showing bizarre levels of elasticity of demand. The $9 charge is clearly very salient and compelling, in ways that other charges aren’t. My guess is that $9 cheaper parking wouldn’t offset it? Of course, if it does, Matt’s right, that’s a win.

At the end of the New York Times article we get this:

Ivan Ortiz, 43, a sanitation worker in Weehawken, said that he would now ask his relatives in Manhattan and Queens to visit him in New Jersey.

That’s an unfortunate change, since it doesn’t alter the amount of traffic, and also doesn’t change the amount of congestion pricing paid – someone has to drive either way and he’s basically trying to use default social norms to shift costs onto others. But also it’s kind of strange, given the costs of parking and tolls (and dealing with the traffic!) was already much higher than $9.

What about enforcement, asks Conversable Economist Timothy Taylor?

Timothy Taylor: New York has been using cameras that take a picture of license plates to enforce speeding laws, and there has been a large rise in the number of cars with license plates that are unreadable for many possible reasons: Buy a fake plate on eBay? Buy a legitimate paper license plate in states that allow it? Hang a bike rack over the license plate?

For $100, buy an electronic gizmo that makes your plate unreadable to the camera? Use certain coatings or covers that makes a plate unreadable? Just slop some mud on the plate? Drive without a license plate? Reading license plates to collect the congestion toll will have problems, too.

I do not understand how this is permitted to continue. The camera doesn’t read the fake and think ‘oh, that’s legit.’ If you are using any of these tactics, the camera system knows damn well you are using those tactics. So does any traffic cop who sees you.

These tactics also are not accidents. There’s no ‘honest mistakes’ here. So make it a rather large fine (as in ‘you might not to claim your car’) to be using such tactics, or worse. Then, when someone tries it, you have incentive to catch them, so you do. And people stop. It’s not like these things happen by accident.

Taylor also considers possible adaptations, with one concern being people who try to park uptown then get on the subway, and worries that the charge is not big enough to reduce traffic that much especially given ridesharing. He also worries about future autonomous cars when they arrive. I expect that would be helpful because those cars will be more efficient.

Does this system favor Ubers and Lyfts? Is it driving down other tolls?

Anne: Ubers & Lyfts circling all day take up more space than commuter cars passing through or driving in, parking & supporting local businesses.

Tunnel & bridge tolls helped support the infrastructure that buses & trains also use; likely fewer of these will be paid henceforth.

I love the new argument that congestion pricing could be reducing fees collected at the bridges and tunnels because fewer people are using them. Sure, to the extent that is happening we should subtract that from net revenue, same with any reduced taxes and fees paid on parking, but it seems fairly obvious that the additional charge for such trips increases net revenue.

The other half here is so strange. What supports businesses other than parking garages are the people, not the cars. It doesn’t matter whether the person also parked a car. Yes, I suppose this means less support for parking garages, hang on while I play the world’s tiniest violin that some of those might transition to something else.

The Ubers and Lyfts take up more space on the roads, but they take up vastly less space in parking lots which is also expensive to provide, and they do so while transporting passengers. About 54% of yellow taxi miles have the meter engaged, and Ubers and Lyfts likely have slightly higher utilization than that due to the algorithms.

If you’re driving yourself and can park at will, you can in theory get 100% of miles ‘on meter’ but realistically you have to park, and people will often be driving someone else and have to go out of their way, and so on. When my in-laws drive us back to the city, that’s 50% utilization for all practical purposes. My guess would be it’s something like 60% for the apps vs. 80% otherwise for time on road. Which is a real difference. But if you count ‘time in park’ then the apps are way ahead, and you at least partially should.

As currently implemented, congestion pricing in Manhattan is highly second best.

Vitalik Buterin: Congestion pricing in NYC seems to be working well so far. Great example of market mechanisms in action.

I wish the tolls were dynamic. Price uncertainty is better than time uncertainty (paying $10 more today is fine if you pay $10 less tomorrow, but you can’t compensate being 30 min late for a flight or meeting by being 30 min early to the next one).

Alex Tabarrok: Exactly right. Tyler and I make the same point about price controls (ceilings) in Modern Principles. A price ceiling substitutes a time price for a money price. But this isn’t a neutral tradeoff—money prices benefit sellers, while time prices are pure waste (see this video for a fun illustration).

As with the rest of this, people complain ‘but that will sometimes cost money and that’s bad, I don’t want to pay that,’ and the correct reply is ‘getting you to not pay that is exactly the point.’

This trades off against higher transaction costs and confusion and stress. Do we want people continuously checking traffic prices and adjusting their plans and having this take up their head space, likely far out of proportion to the charges involved? What we actually mostly want is for people to shift into relatively good habits and patterns, I think, rather than to respond that much in real time to conditions. So my guess is we want a compromise – we should be doing more to charge extra at rush hour and other expected peak times, but in predictable ways. We already do a bit of this with night and weekend discounts.

The other flaw is that we are not charging people for trips within the zone, except for taxis and rideshares. We can and should fix that, if your car is on the street within the zone at all you should pay the charge for the day, for the same reason everyone else pays. Tyler Cowen blames this on political economy, my presumption is it is actually about enforcement being a lot easier if you only have to watch the borders.

Matthew Yglesias: I think a city that did congestion pricing outside the context of a transit budget crisis and simply used the money to cut sales taxes would find it to be an easier proposition.

Nobody likes taxes.

Even low-tax jurisdictions have taxes.

You might as well implement a tax that yields non-fiscal benefits.

This would obviously be a great idea, so long as there was substantial congestion that you would want to price. But no, I don’t think this is how it works. People don’t respond to this kind of logic. If they did, we’d all have carbon pricing by now.

When I look at the pure vitriol coming from congestion pricing opponents, I do not get the sense that it is at all tied to a budget crisis. I also don’t get the sense that ‘but we cut sales taxes’ would make them feel better.

Indeed, I think it would make them even more mad. They’d say you were taxing poor people’s cars and using it to discount rich people’s lattes.

It will be a few months before we have enough different conditions, and enough time for adjustments, to start to draw robust conclusions about effect sizes. A lot of this is complicated by the gradual rebirth of Manhattan in the wake of Covid, with trips into the city up substantially year over year for other reasons, and by the partial implementation via most of the taxi congestion charges having already gone live before.

Certainly this wasn’t a fully first best implementation. The prices are almost certainly too low, and we need to charge for travel within the zone. But it’s a great start.