Previously: Book Review: On the Edge: The Fundamentals

As I said in the Introduction, I loved this part of the book. Let’s get to it.

When people talk about game theory, they mostly talk solving for the equilibrium, and how to play your best game or strategy (there need not be a formal game) against adversaries who are doing the same.

I think of game theory like Frank Sinatra thinks of New York City: “If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere.” If you can compete against people performing at their best, you’re going to be a winner in almost any game you play. But if you build a strategy around exploiting inferior competition, it’s unlikely to be a winning approach outside of a specific, narrow setting. What plays well in Peoria doesn’t necessarily play well in New York. (841)

If you build a strategy around beating a specific type of inferior competition, and you then face different competition styles, you either adapt or you are toast.

If you build a strategy around identifying and dominating inferior competition in general, then you might be a very good poker player.

Especially if you also are prepared to fall back into game theory when needed.

(See for example my experience with Simplified Poker.)

One thing I have always believed is that true randomization is often highly overrated.

Poker—yes, there is a solution to poker, though as you’ll soon see it’s an exceptionally complicated one—involves lots of randomizing. Randomizing between calls and raises, between calls and folds, or sometimes between all three. It’s not just that you should play different hands in different ways; you should play the same hand in different ways. (949)

Yes, the pure game theory solution involves heavy randomization.

In practice, however, true randomization is only necessary if being non-random would be detected by the opponent in an exploitable way, and they would exploit it at least as much as you could exploit them.

Thus, if your decisions are effectively, from the opponents’ perspective, sufficiently random or unpredictable already, you do not need to then explicitly randomize further. One way for this to happen is if your hidden information influences your model of what they are likely going to do, because it changes what information they might have had in turn. Another is if they simply do not yet have enough data to anticipate your actions.

You always do have the option to fall back upon the game theory in a pinch. And indeed, if I was playing Nate Silver for sufficiently high stakes, that is exactly what I would do, to the extent I knew what the game theory solutions were.

If you don’t know the odds and solution, you’ll need to approximate.

Long before the advent of personal computers, Brunson and another Hall of Fame player, Amarillo Slim, would deal out thousands of poker hands to themselves to get a more precise sense for the probabilities. (659)

It’s fascinating to think that ‘deal out thousands of hands of 22 vs. AK’ is faster than doing the math on it, if you don’t have a computer handy. My first instinct was ‘of course I would simply Do the Math’ but then I thought about how I would actually go about doing that, and now I realize I’m not so sure how to be more precise (with only the technology available at the time to Brunson) than dealing it a thousand times.

Eventually, of course, we got the computers, and now we can solve for the equilibrium. Thus, AIs can now defeat all human poker players.

There’s never going to be a computer that will play World-Class Poker. It’s a people game. —Doyle Brunson (625)

But the claim that a computer would never play world-class poker? That might be the worst bet Brunson ever made. (640)

Sure enough, though, another AI poker bot—a descendant of Polaris named Libratus—won a heads-up no-limit challenge in 2017. And then, finally, another younger sibling called Pluribus beat humans in a multi-way no-limit match in 2019. (746)

Brunson’s claim is that the ability to read, understand and exploit humans is too valuable, including the crucial skills of convincing that human to keep playing in games where they are going to lose and to do so for high stakes in an imprecise way, so a computer will never do as well in practice as a human.

In the long run, Brunson will be wrong about that. But if you were betting on the WSOP main event, which do you think would have higher EV- a computer playing fully GTO (game theory optional) or Thomas Rigby (‘the Stoic’) putting maximum pressure on everyone? I am very convinced that at least through about day 5, Rigby is going to do way better. And if the question is, who will make more money trying to put together a cash game, again you want to go with Brunson.

For now. Eventually, the AIs will also get much better at everything else, too, and Brunson will be fully wrong.

But also ask the question, did Brunson lose that bet? Yes, he gets quoted as being wrong in a book in 2024, but did he end up worse off on net?

Always remember the odds.

One fun thing about poker AIs is that they bluff a lot more than the most successful humans used to, and mix up decisions more often.

The frequency with which the computer liked mixed strategies was surprising to Lopusiewicz, who had never formally studied game theory. “I knew that there was going to be a lot of mixing, but I didn’t realize it was going to be on almost every hand,” he said. (1037)

Computers bluff their faces off when playing poker because that’s what game theory says to do. This can include making big bluffs—going for a knockout punch. But more often, they prefer small, tactical bluffs—say, betting $20 into a pot of $100—the equivalent to a boxer’s jab. (1059)

My intuitive way of understanding this is that it is very hard to maintain ‘balanced ranges.’ If you bet small, you need to bet small with a wide range of hands at different times, such that opponents cannot ‘smell weakness’ and raise, or trust you too much and consistently fold. Same goes for your big bets and your checks (not betting), and your raises and calls, and so on.

That means you need to mix up your decisions a lot, in order to put your opponents into bad spots while not giving anything away. Humans in practice find this difficult, especially sacrificing EV to do ‘unnatural’ things so often. AIs showed them why they have to do this anyway.

There are a few asides on randomization in baseball and other sports. Obviously if you are a pitcher, you need to be mixing up your pitches, so they don’t get to look for a particular pitch. If you don’t think you can actively outguess hitters, you want to use randomization.

And yet, Verlander throws his fastball only about 50 percent of the time. How come? Well, major league hitters are pretty good. And although Verlander’s fastball is tough to hit, it’s easier if you know that it’s coming. (970)

Greg Maddux—one of the most cerebral pitchers of all time—reportedly did exactly this, using quasi-random inputs such as the stadium clock to decide what pitch to throw. (992)

In sports, a play like a fake punt is terrible if the other team knows it’s coming, but it can be a great play if the opponent isn’t anticipating it. (996)

Exploit and you risk being exploited. (1071)

If you throw your fastball too often, everyone will figure that out. If you have a pattern that is too obvious, they will figure that out too, more so today than in the past. The same goes for many other similar choices in sports.

The question is, to what extent do such worries have to ‘keep you honest’?

There is obvious danger in being too predictable. But in general I see too little exploitative play attempted, not too much.

This is especially true when the decision is asymmetric, and when the opponents’ decisions can be observed.

In football, you can see how the defense sets up play after play. They can surprise you, but their decisions are observable on every play and a given formation will limit their options. In particular, if they decide to pack a lot or only a few players into ‘the box’ to defend against the run (as opposed to defending against a pass), that tends to be mostly consistent between plays and has a big impact. And with a given matchup between teams, it often quickly becomes clear what offensive options are +EV, and which ones are not working.

The best offenses will then ‘take what the defense gives them,’ and repeatedly exploit the opportunities they see each play until the defense adjusts. Yes, they will mix up their play a bit, but if they see soft coverage that allows an easy pass, or there isn’t enough good run defense, they will pound you play after play until you fix it.

Whereas others often end up with what I call a Running Running problem.

It is totally fine to have a Running problem, where the defense is ‘taking away’ your ability to successfully run. Pass the ball.

What is not okay is when teams are in this spot, and then they run the ball half the time anyway. That’s the Running Running problem – you have a Running problem that you can’t run, and then the problem is still running.

The happens when the coach either feels the need to ‘establish the run’ or to give the impression that they might run on any given play. Otherwise, the defense would be able to adjust. But you can skip all that. Then, if the defense does adjust? Now you run. Or, in reverse, with the pass, once they start moving everyone to run defense.

If the defense proves so good at anticipation and adjusting that they can outguess you, and is mixing up their own play smartly? Retreat to game theory. But if they’re predictably exploiting you, don’t sit there wasting plays that predictably fail.

Another phenomenon we see is teams ‘saving their best plays’ for high leverage situations. In those high leverage situations, where the play matters most, they turn to their best plays and players and pitches and so on more often. So essentially they are playing a mixed strategy in other spots, where they do their weaker options ‘too much,’ then switch when they need a win.

In theory, aside from hiding truly unique new plays, this shouldn’t work. The other side should do the same adjustment, and anticipate that the offense will call its best play, or the pitcher will throw their best pitch. And if that adjustment wouldn’t work to stop it, then why isn’t the offense calling their best play every time?

But somehow this does work in practice. People get into a rhythm. In baseball this makes more sense, because you want to vary selection in part to make it hard for the batter to calibrate. In other sports, it’s weirder.

Most people do not understand the underlying math or logic of most of what they do.

Instead, they have memorized a bunch of rules or heuristics and copied behaviors. That works 99% of the time for 99% of things. It is typically wise.

When you ask them to solve a new problem, that’s different. Whoops!

Although solvers might seem like a natural fit for Selbst, whose mother drilled her on logic puzzles when she was growing up in Brooklyn, she’s instead a deep believer in exploitative play: figure out what your opponents are doing wrong and take advantage of it. “Most people—save like the best hundred people in the world,” she told me one day over happy hour drinks at a Manhattan wine bar, “just aren’t that amazing at game theory.”

Instead, Selbst says, players have a lot of experience in situations that come up frequently in poker.

But memorizing only gets them so far. “They were very good at playing a spot 1,000 times and knowing what to do in that spot,” she said. But she found “that over time, whenever I put someone in a new spot, they would just royally fuck up.” (1116)

Poker is a compact game, such that it should be difficult to put someone in a truly unique spot. But sometimes it can happen.

The same thing also works in other games. This is the joy of the rogue Magic deck, when it is doing something others haven’t seen before. Or the unusual opening in chess, to take the opponent out of not only their ‘opening book’ but their principles for afterwards. Put them in a spot where you know everything, and they don’t.

Even if you are capable of solving the game theory or other puzzle given time to think it over carefully, you do not have that time. You need to make a decision now. Nor do you get to use trial and error, or get to study up.

The trick is that you have to give up less value in your unique play, which almost has to be an inaccuracy to work, than they give up not knowing how to respond.

My favorite poker version of this is watching Phil Hellmuth, who Nate Silver reports is exactly who you think he is from watching on television.

Phil Hellmuth spent about forty minutes showing me his trophy room. (1648)

When we later sat down at the dining room table in his comfortable home in Palo Alto, California, it was clear that my effort to tamp down Hellmuth’s ego had failed. He spoke in a fifteen-minute stream-of-consciousness soliloquies where I couldn’t get a word in edgewise. (1652)

Why craft a persona, when you can use your own genuine one?

Phil’s entire strategy is based on using a pattern designed to provoke the opponent into playing exploitatively or drive them into various forms of tilt. And then, through decades of experience, to know all the different ways players respond to that, and what to do about each one. Its seemingly obvious weaknesses and patterns are a feature.

You, at home, see what is happening and are screaming. But if it was you playing then he would pick up on your response pattern, and be using a different variation.

He combines this with his ‘white magic,’ his ability to read people, especially to read people in how they react to him, where his unique style and reputation make them have less effort available for mixing up play and being hard to read.

But one important connection Hellmuth drew is that his white magic comes and goes with his energy level. The idea that people-reading ability comes from the body rather than the mind—so that when we’re tired, our social skills suffer more than, say, our ability to work out an equation—is something straight out of Coates. “Sometimes I’m at full fucking reading ability. And when I’m at full reading ability, I’m dangerous,” he said. “Why don’t I have more bracelets than I have? (1689)

“What’s happened is fatigue has killed me. So I get too tired. And I lose control. And I play badly.” (1694)

Then every so often (for example, on High Stakes Duel) he runs into Jason Koon who ignores all that and plays GTO (Game Theory Optimal) while ignoring the antics, and Phil gets destroyed. Whoops!

Same goes for non-game actions too. If you are out of your comfort zone, in a new situation, you will handle pretty much anything vastly worse at first, no matter who you are or how calm you are, versus how you’d handle it the 10th or 30th time. That’s unavoidable.

The fatigue thing is a huge deal as one gets older. The reason I no longer go to Magic tournaments is partly because I am too busy, but mostly because I lack the stamina. There’s no way for me to bring my A-game for three full days. That’s also the reason I probably won’t ever play the WSOP.

Another mysterious thing is that idea that ‘the body knows’ tells rather than the mind.

“One thing I found out really quickly when I first started playing was I had a really strong instinct for when my opponents were weak or strong,” said Maria Ho. (1722)

Coates told me something similar: we should generally pay attention to the signals our body is providing us with even if we can’t quite figure out why. “The thing is our physiology is really smart,” he said. “I mean, it’s just really smart. It’s very hard to trick your physiology…. (1735)

I am, as one would expect, skeptical of this explanation. I don’t deny their lived experience. I’ve certainly had plenty of situations in which I had that same kind of intuitive or instinctive sense about things, including what was up with someone. Over time you learn when you can trust that, and when you can’t.

I don’t see it as coming ‘from the body’ or physiology in the way Ho and Coates are describing here. To extent that this seems like a real thing I can think back upon, I would think of that as the method of getting the output rather than how one is doing the calculation.

As in, Coates has found that when his unconscious analysis picks up on something, it causes physiological reactions, and it is easier for him to notice the secondary physiological reactions than it is to tune (directly or not) into the output another way. And that this is true even when you cannot trace back the reason.

I suppose it mostly adds up to the same thing?

A last note on tells is a warning not to focus on physical patterns too much.

“Even against bad players, the relative weight of the physical thing is usually pretty low,” Adelstein told me. “You really need some really great information, specifically like them doing that physical thing when they either almost always have it, or almost always don’t, over a pretty good sample size.” (1735)

I am highly convinced that most Magic players have rather obvious physical tells, if you were able to watch for them carefully over enough matches. Myself included, and I put considerable effort into not doing that, partly into the obvious stuff that people do notice, and partly into more subtle stuff I doubt almost anyone ever saw. But in general, actively focusing on trying to find the physical tells of others beyond a few universal patterns was a fool’s errand, as you were better off focusing on other things.

What Nate relies upon most, and feels are reliable enough to be good, are stereotypes.

Because it’s a game of limited information. So you’ve got to take whatever you can get. And I will say most of these stereotypes are correct 70 percent of the time. (2112)

Seventy percent is pretty good. The thirty percent of the time they’re wrong, you get burned, especially since they likely know what you are expecting, but that’s a risk you have to take. That’s poker. You can’t afford to disregard Bayesian evidence.

Here is something I wonder about.

“If there’s one thing that you figure out after many, many, many, many hands, it’s you know what 52/48 is,” said Annie Duke, referring to a player who can distinguish a 52 percent chance from a 50/50 spot. “That’s the type of distinction that most people are very bad at making. But poker players are really good at making that distinction, and they can feel it.” (1771)

Sports betting in particular absolutely does give you this feeling. You know in your gut what 52/48 (also known as -110) looks and feels like.

When I played poker, I did not feel I was learning to do that. Sure, I knew the odds, but none of it felt that kind of precise. It never felt so important. What exactly do you do with that information? In sports knowing that the game is priced 52/48 instead of 48/52 is a huge opportunity. In poker, that is a small mistake, and it does not seem like you get enough feedback to realize it – you’d have to get that distinction from a solver, or from doing some sort of abstract math.

One of the lessons from Jane Street that I can share is the idea that you should consciously choose to have the proper emotional reactions to events. Traders talked that way. They did it on the direct level: ‘I’m sad about [X]’ or ‘I’m happy about [Y].’ And also on the intention level: ‘You should be sad about [Z].’

You are training your brain. Providing it with feedback, so it can learn. You want to give it the correct feedback. For humans, in practice, that in part means the correct emotions.

So what if you could replace traders—or poker players—with AI systems and not have to worry about all that icky body chemistry? Actually, that might not be such a good idea. We get a lot of feedback from our physical beings; this is one reason some experts are skeptical that AI systems can achieve humanlike intelligence without human bodies.

In fact, Coates’s studies found, the most successful traders had more changes in their body chemistry in response to risk. “We were finding this in the very best traders. Their endocrine response was opposite of what I expected when I went in.” (1551)

The AI systems, if they could otherwise replicate the traders, would actually be an insanely great idea. They’d have huge advantages, including faster speed, more memory and ability to learn and absorb data in real time and overall, and so on. And they would absolutely find alternative feedback systems to capture these benefits.

What you would not want to do is give these humans pills that dulled their responses.

The other key is, you don’t want that to be about winning or losing money…

“We’ve wired up traders that were big hitters, and they were poker-faced,” he told me—the traders occasionally got angry when things were going poorly but mostly kept a calm demeanor.

“But even when they were poker-faced, what was going on under the surface was far more important because their endocrine system was on fire when they were taking risk.”

In one experiment, for example, Coates studied the testosterone levels of a group of traders at a high-frequency London trading shop. He found that their testosterone was significantly higher following days when they’d made an above-average profit. But the converse was also true.

Coates had also been checking their testosterone in the morning and discovered that they had substantially better trading days when they woke up with higher T levels. Higher testosterone predicted more trading success, in other words. (1528)

Raising testosterone after a good day means you’ll likely be more aggressive and go larger and faster and break more things. It also means you are going to feel good about things having gone well. Neither of those seems ideal? Focus on the process, not the outcome.

What to make of higher T being actively predictive of better results? This could be causal through any combination of things such as greater energy, higher status or willingness to take more risk.

Or it could mainly be that higher T was predictive without being causal, and traders had an idea of when they would make more money. If you are waking up for a big day, say triple witch or Fed day or an important earnings day where you get to make the decisions and you’re prepared, you are going to be more excited. Momentum effects would also do this, or anticipation of realized gains, and so on. Makes sense to me.

Similarly, I bet that back when I was competing in Magic, this correlation would have held, but that was likely mostly predictive rather than causal – when I had a big day or a great deck or opportunity, I was going to be more pumped.

In big moments when you’re confronted with a high-stakes decision, you’re essentially working with a different operating system than the one you’re used to. (1571)

However, it helps to have practice under these conditions. In fact, having a physical response to being confronted with risk can be a healthy sign. Coates was once contacted by a group of researchers with the Great Britain Olympic Team. Their best athletes, they told him, were just like his best traders, with low baseline levels of stress response that then dramatically spiked when it came time for a big competition. This even applies to golf. (1573)

My own research shows that experience matters considerably in the NBA playoffs. And we shouldn’t neglect the testimony of athletes themselves, from Michael Jordan to the great Montreal Canadiens goalie Ken Dryden, who describe similar experiences of being in a zone when under intense pressure. (1602)

I can confirm.

And this makes me think it is at least plausible that ‘big game experience’ is a real factor in the playoffs, including in the NBA. You learn to handle the moment. But also I know the gambling market mostly does not care, to the point we ignored it when predicting future market prices and that seemed fine.

Also I notice exactly when I had that big stress response for the big competition.

It wasn’t during the competition, when decisions were being made. It was directly before the competition. Same was true with exams. Hugely nervous while hurrying up and waiting. Completely calm once the exam started.

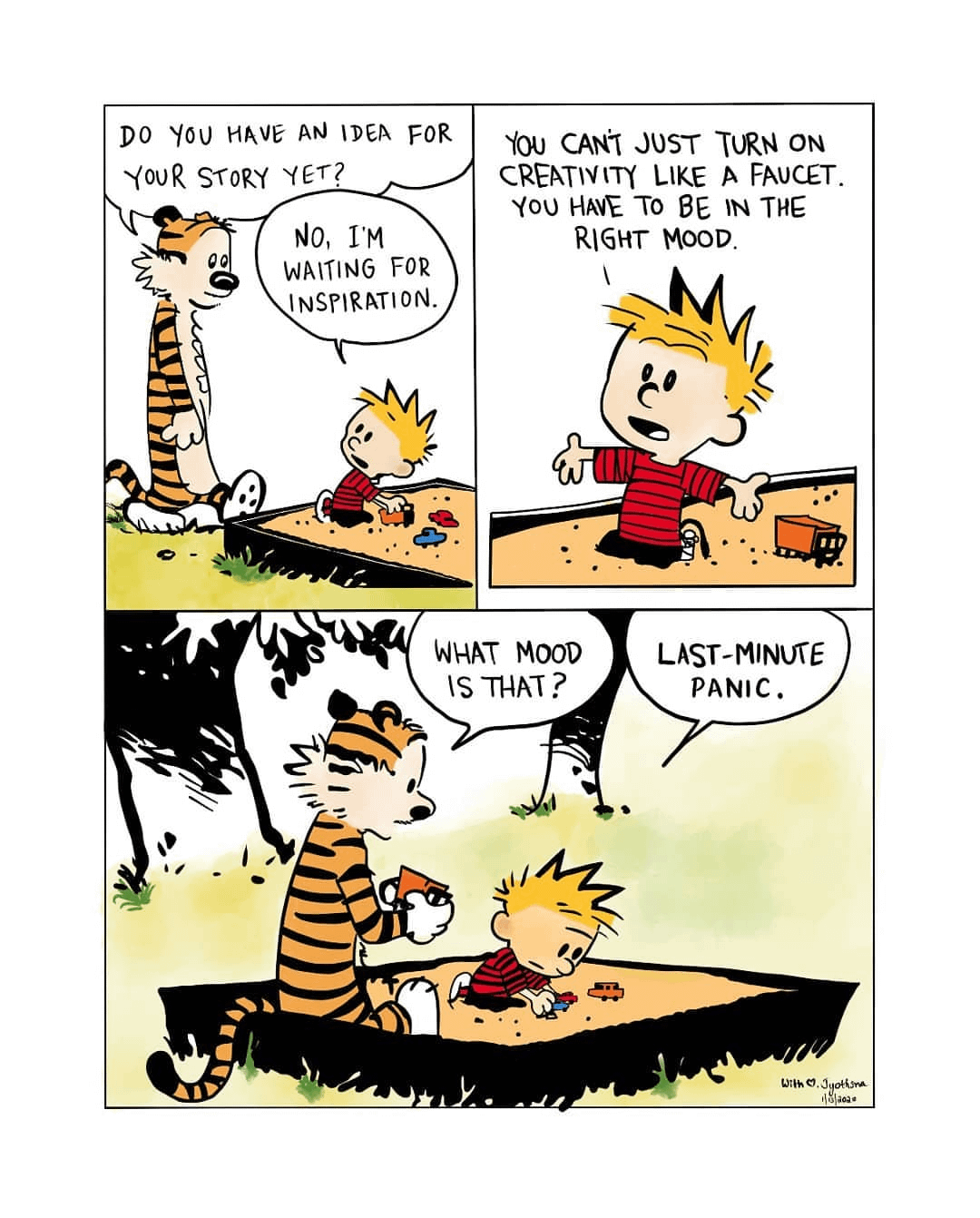

When I think about the times I’ve been in a zone or flow state, it’s often been in response to stress. It’s happened at big moments in poker tournaments, occasionally during public speaking appearances, and even a couple of times when I was writing or coding under intense deadline pressure.

I’ve also had it happen on election nights when I’ve been covering the results. What these had in common is that they were all extremely high-stakes moments where I had thousands of dollars in money or future earning potential on the line. (1582)

That was not true for me at first. I was nervous as hell early on during big matches. But I learned over time not to do that. It was not helpful. Instead, you went through the stress beforehand, and then sat down and you were in the zone. It was like any other match, except hopefully more dialed in.

And yes, it very much helped to have played on the biggest stage. I was able to handle my first time because I was (not coincidentally) Crazy Prepared that tournament. After that the pressure mostly didn’t phase me anymore. Nate Silver has the same story, where he made a deep run into the top 100 at the WSOP main event only to lose to a set-over-set cooler where he 100% was absolutely supposed to go broke every time:

It was heartbreaking. I may never play such a big pot again in my life. But I’ll tell you something: ever since that hand—losing the equivalent of a nearly million-dollar pot that for a split second I’d assumed I was a big favorite to win—a bad beat for $300 or $3,000 or even $30,000 hasn’t felt like such a big deal by comparison. There’s nothing like pain to build up your pain tolerance. (1644)

There are other times, especially when working open ended on something important, when the stress is a huge negative, a distraction, causes aversion and procrastination, gets in the way. That happens largely because there is no clear dividing line when the battle starts. One response to this is to wait long enough that it is clear the battle has indeed started, and you have no choice, as in:

It’s not panic. It’s the stress of the upcoming need to work, of the decision whether to face the problem, leaving the body. You’re in the zone, baby.

Tendler referred me to a set of research called the Iowa Gambling Task, so named because it was originally conducted by professors at the University of Iowa College of Medicine.

It works like this: participants are asked to choose from four decks of cards—A, B, C, and D. Each card gives the player a financial reward or penalty.

Two of the decks—let’s say A and B—are risky, with occasional big wins but lots of penalties and poor overall expected value.

The other two—C and D—are safer, with a positive expected return.

The pattern isn’t that subtle, and after turning over a couple dozen cards, the player usually figures out to avoid the losing decks. The research found, however, that players have a physiological response to the risky decks before they detect the pattern consciously.

Their body is providing them with useful information—if they choose to listen to it. (1586)

This is one of those studies that drives me nuts. Why would you hopelessly confound your study like this, combining risk level (high versus low) with expected value (positive versus negative)?

What was this physiological response telling us? It could be any combination of:

-

The deck is risky, oh no.

-

The deck is -EV, oh no.

-

I am probably going to get penalized, oh no.

-

I am buying information, but I expect deck to usually be -EV, oh no.

The researchers are perhaps assuming that the players are picking up on the -EV. That does not seem so likely to me. Instead, my guess is the players physiological responses are mostly noticing the risk, which the players obviously did consciously notice the moment they see the first big negative card.

The proper experiment, of course, is where (with names randomized per player):

-

A and B are risky, C and D are safe.

-

A and C are profitable, B and D are unprofitable.

Even worse, notice that A and B have lots of penalties and only a few big wins, rather than the other way around or being symmetrical. That confounds us even more. Even better would be:

-

A, B, C and D are risky. E, F, G and H are safe.

-

A, B, E and F are profitable. C, D, G and H are unprofitable.

-

A, C, E and G have mostly small plus cards and some big minus cards. Whereas B, D, F and H have mostly small negative cards and some big positive cards.

-

The numbers are randomly shuffled enough it isn’t too obvious right away.

Then see what happens.

Is it, in general, not taking one? The claim here is essentially yes.

For the most part—at least when it comes to financial and career decisions—people do not undertake enough risk. It’s certainly true in poker. For every player who’s too aggressive, you’ll encounter ten who aren’t aggressive enough. (1536)

It’s true in finance, according to Coates. “A lot of asset managers and hedge funds I’ve dealt with have a problem getting their good traders and PMs to use their full risk allocation,” he told me. “They’re not taking enough risk.”

It’s true when people are contemplating personal changes. Annie Duke’s book Quit—Duke is a former professional poker player who quit the game in 2012 to study decision-making—is full of evidence about this.

An experiment conducted by the economist Steven Levitt, for example, found that when people volunteered to put major life decisions such as whether to stay at a job or in a relationship up to the outcome of a coin flip, they were happier on average when they made a change. (1538)

Faster, you say? Not so fast!

At one final table of the World Series of Poker (WSOP) main event, one player had a sheet of paper with reminders. One of them was: Folding is only a small mistake.

This is very much a case of Reverse All Advice You Hear. Some of us need to learn to fold less and play loose. Others need to learn to fold more and play tight. Mostly players need to fold more, because you can’t win by folding, and folding is not fun, and the amount you should be folding is not intuitive. But there are big exceptions.

What that has in common with aggression, and with risk taking in general, is that making a mistake is an asymmetric risk. In most situations, from most perspectives, being too aggressive and taking too much risk is a lot worse than being too passive and not taking enough.

You would much rather be betting half of Kelly than double (or 1.5x) of Kelly. It’s a skill issue too. If you have a skill problem, aggression will be harder, and make things vastly worse for you. Which, in turn, can compound your skill issue, because you do not learn. You’re only ‘not taking enough risk’ if you know how to take smart risks.

Amusingly, the Kelly criterion didn’t actually get a mention until near the end:

If I had laid odds, you ought to have bet on me mentioning something called the Kelly criterion before now in a book about gambling. (7193)

Poker is a special case where the baseline aggression is indeed way too low, and by default most players are too passive – good poker is tight and aggressive, whereas most players are relatively loose and passive.

In finance, notice the adjective ‘good.’ It’s hard to get the good traders to take enough risk. The bad traders? You wish they’d take less. Often they take way too much, or you’d prefer they not take any.

A good trader learns to make the small mistake of not going big enough, to wait for the best opportunities, and also to protect the downside or risk of ruin. They place high value on survival, and know that being down a lot less than 100% can still be fatal if you have a manager.

As the asset manager, sure, if you know who your best trader is you want them taking more risk. That’s your incentives, not theirs.

What about quitting or otherwise making major life changes?

There are a lot of factors here.

-

A lot of it is that big changes, and big risks, tend to be negative in the short term, and often involve a blast radius. Breaking up is hard to do, and it sucks, even when there’s nothing tying you down. Quitting your job hurts the company you leave behind. Moving is a huge pain. Trying and learning new things is a lot of work, at first.

-

We want to be able to make commitments and honor them. If you’re on the fence about breaking your commitments, then probably yes you will be happier if you break them, but you should have a higher threshold than that because it also matters that you don’t do that.

-

We want to guard against errors and momentary preference changes. A relationship won’t survive for long if either party is willing to leave it on a whim, or whenever they think they can do 25% better.

-

If you ‘take the risk’ and make the change, then what happens is Your Fault. You did the action, so you’re blameworthy. If you do nothing, then it isn’t your fault. Or at least, you can tell yourself that.

-

Also there are various biases that hold you back and shouldn’t, including bewaring trivial inconveniences or The Fear.

-

If you are considering doing [X] continuously, on the fence about it, then the cumulative chance of doing [X] could end up very high while you feel indifferent about the decision at any given time – so on average [X] would be wise.

-

Finally, such studies are usually medium term, which also excludes the long term. Often sticking with things means making a long term investment.

The generalization is that you almost certainly want a decision policy, whereby when you are not sure what to do with the decision whether to take risk or make changes, on average the active risky decision will make you happier in the medium term.

Perhaps the question on changes should be: If this was the last moment I could possibly do this, and someone else was advising me, would they advise me to do it?

Playing in cash games is low variance. Table selection is huge, but for most purposes each pot is independent of each other pot. So as long as you hold your stakes relatively steady, you’ll get ‘justice’ over a not-too-long period most of the time.

Grind out the $2/$5 game at the Bellagio for fifty hours a week, and you might have an expected value of $80,000 to $100,000 per year with little risk of going broke. But the idea of regular hours and a steady paycheck defeats the purpose of playing poker in the first place. (1910)

So instead the real action for a lot of players ends up in tournaments. The problem with tournaments is that payouts are extremely top heavy, so even over long periods you can be +EV and yet run very poorly.

I had the same issue when I was trying out Daily Fantasy Sports (DFS) for a brief period. Me and my DPS partner together managed to consistently have lineups that posted above-average mean scores, while also having higher in-lineup correlations.

We should by all rights have done well, but to take advantage of the correlation advantages we had to enter big tournaments. At one point we went into the last game of the Sunday Millions on FanDuel with a substantial chance of winning outright. But we never spiked that big win, and the edge you need without spiking that huge win is utterly massive. For that and other reasons, I gave up and ‘got a real job’ instead of continuing.

Poker players hate real jobs. Indeed. I knew, quite obviously, that getting a job at Jane Street or another firm would pay vastly better and more consistently than gambling. I figured I had what it takes. But who wants that? Indeed, exactly that issue – Jane Street is a great place to work, but not wanting a ‘real job’ where one had to show up and be ‘on’ in the right way consistently, was why that job did not work out for me.

It’s a field that glorifies hyperrational decision-making, but a lot of people who play poker for a living would be better off—at least financially—doing something else. The combination of mathematical and people-reading skills necessary for success at poker should generally also translate to lucrative opportunities in tech, finance, or other River professions—usually in jobs with health care benefits and far less variance. However, much of what attracts people to poker is an anti-authority streak. It’s one of the only professions where you can truly be a lone wolf. (1913)

The poker version of the variance problem is even worse.

We specified that this player is a step short of elite, but somewhere between the one-hundredth and two-hundredth best player on the live tournament scene—a good regular who you’re never happy to see at your table. Let’s call her Pretty Good Penelope. (1810)

What’s the bottom line? I estimate that in an average year, Penelope will earn about $240,000 from tournaments. “Wow, that sounds pretty great!” you might say—travel the world, play cards for a living, and make several times the average American salary.

That doesn’t really tell the whole story, however. For one thing, there are taxes (a big issue based on the way the IRS taxes poker players) and expenses (high, since we’re assuming Penelope’s on the road about a hundred days per year).

But the big problem is that the $240,000 figure is kind of fiction. It’s an expected-value calculation over the long run, and Penelope is never going to reach the long run. There’s so much variance in tournament poker that even if Penelope played for fifty years, the swings wouldn’t really even out.

In fact, despite being one of the two hundred best tournament players in the world, she’ll have a losing year almost half the time. I discovered this by simulating Penelope’s schedule ten thousand times, using payout tables from actual poker tournaments. There’s one other question you might ask: Penelope intends to spend more than $1 million in tournament buy-ins per year—so where the hell is she getting all this money? (1860)

Even more than gamblers, Magic: the Gathering professionals are punting massive amounts of equity to get the lifestyle they want. If you can win Magic tournaments, you can win at far more valuable activities. If you ever have a chance to hire former or current Pro Magic players, as I did a few times, you jump at it – they are whip smart, they are severely underpriced, they are great to work with and play to win.

The good news for us was that Magic tournaments are far less random than poker tournaments. Skill plays a bigger role, and plays it far faster. It is highly practical to consistently do well, and to have a substantial chance of winning out of a field of hundreds or even thousands. Poker is not like that.

The thing about poker tournaments is, even if the EV is lousy and the variance is gigantic, they are still very clearly awesome. They’re fun, they’re exciting. I feel the pull. If there were local tournaments and I wasn’t going to get completely killed I would likely sometimes attend them.

Degen means degenerate gambler. A degenerate gambler loves the action. They’ll bet on anything and everything, often without an edge. They’ll bet too big and risk going broke, when it makes no sense to do that, even when they otherwise have it made.

(Being considered a degen is sometimes a badge of honor in the River, so long as you’re not the sort of degen who harms others. Better a degen than a nit, certainly.) (1955)

I am not a nit (or like to think I’m not!) but I am definitely not a degen. You will not see me take zero EV bets. The idea of being +EV and then losing is fine, but the idea of making a -EV gamble (as an actual mistake, rather than e.g. part of a strategy that makes a set of gambles some of which need to be -EV) fills me with dread. I hate mistakes with a passion. But I also realized that while you could always choose to do nothing, holding back when you shouldn’t, not deploying your capital when you had a great opportunity, or waiting too long, or being too careful with your bankroll was also a mistake.

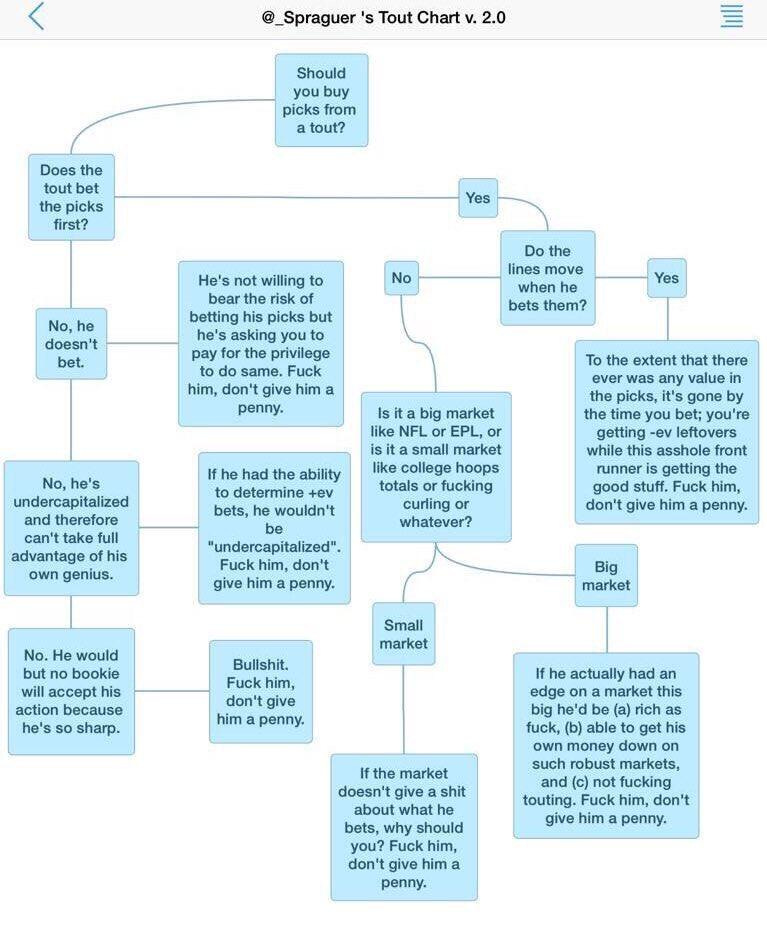

I then discovered a funny thing about sports betting. Essentially all the most successful sports gamblers are degens.

It seemed possible I was the most successful sports gambler who wasn’t a degen. Almost no one who has to teach themselves to be fine with risk, rather than loving the action, gets all that far.

Later, we see a claim to the contrary, from sports gambler Spanky.

Spanky claimed to me that this suited his personality. “I don’t like gambling really. None of us like real gambling. We like winning.” (3082)

Yeah, I have no doubt Spanky said that, and he might even believe it. It might be true of him in particular. In general? It’s simply not true. They like winning. They would probably not go so far as to say ‘the best thing other than gambling and winning, is gambling and losing.’ But they like gambling.

I made sense of this by reading the forums where non-degen ordinary gamblers discussed their strategies. In particular, where they discussed their bankroll management.

You’d have people who would bet 1% of their bankroll (total amount they had to gamble with) per normal game, and picked spots carefully. Then, if they had a game they truly loved, maybe they’d go up to 3%.

Which sounds all safe and responsible and reasonable, until you realize they had a bankroll of something like $50,000 and every month they had to pay their rent. So they would have to net win something like ten bets every month in order to break even. Or they wouldn’t be paying rent off the bankroll, but they’d have a tiny one, e.g. $10,000, and they’d be acting like losing it was infinitely terrible.

A lot of them of course did not have +EV, and lost. But what happened to a lot of the ones that were indeed +EV, was that they’d do this for a few months, and they’d win, but they wouldn’t end up with a much larger bankroll than they started with. Meanwhile, their life was ending one minute at a time. What was the point?

When I watched the true degens, I saw that they were (mostly) the only ones able to move boldly, for size, when opportunity knocked. They were the ones that got into position to play for size, and also the ones that took advantage.

The downside, of course, is that degens can make rather large mistakes, either in EV terms or in terms of risking a true blowup. And yep, I saw a bunch of that too.

The whole degen attitude, to me, is kind of weird?

That’s another thing you might not expect about high-stakes players. They tend to be generous with their money: tipping well, loaning to friends, offering to pick up checks, and so forth. Relative to other successful people I’ve met, they’re more aware of the ephemeral nature of money and the role that luck has played in their success. (1960)

My brain thinks this should work the other way around.

If you are drawing a steady paycheck, then you can be super generous. You get X dollars per year in income, you have Y in expenses and Z in savings, so you know what you can afford to spend to help out the less fortunate, or on a luxury.

Now suppose you are a gambler. Maybe you’re Penelope the pretty good tournament poker player. She could go an entire year, play her A-game, and lose money. Two years from now, she might be broke as she throws $10k after $10k at tournaments and fails. If she struggles, suddenly she’s going to need every penny she can get.

There was a period where I was gambling, and most of my net worth was in my formal bankroll. I was very careful with my expenses, so I could afford to take risk gambling.

When I look at poker players being ludicrously generous in these ways, without longer term financial security, it seems insane to me.

Yet it is a common pattern. Those who come into cash at random tend to be generous with it, for themselves and for others. They make it rain. Even when they know full well if asked that there will come a day they will again be broke or close to it.

Some of that is that such people often understand that they face various wealth taxes – pressure to distribute their gains over time, or inability to collect various benefits and opportunities. So instead they invest in experiences and social capital.

With poker players, I am guessing the core idea is the same. You come into cash. You know that you will probably find a way to blow it, and are now expected to be more generous in various ways, to gamble higher, and so on. So you act generously now, enjoy your winnings, and build social capital. Then you can ‘afford to’ go broke later.

People have a variety of different and bizarre relationships with the concept of luck.

Some people even think they are lucky, or others are lucky. Poker players especially seem to think this reasonably often.

Odo (From DS9, and often): “I don’t believe in luck.”

Michael McDermett (Rounders): Why do they insist on calling it luck?

Many Magic players (often): Better lucky than good.

Spider Murphy (from Cyberpunk/Netrunner): If someone has consistently good luck, it aint luck.

I don’t consider people ‘lucky’ per se outside of a particular context. But there is the theory that ‘thinking of yourself as lucky’ is good.

Richard Wiseman’s 2003 book, The Luck Factor, asserts that people who view themselves as lucky benefit from it in several ways.

Here’s a version of his claims:

Lucky people “constantly encounter chance opportunities” and try out new things. Lucky people “make good decisions without knowing why.”

They listen to their intuition.

Lucky people have positive expectations so their “dreams, ambitions and goals have an uncanny knack of coming true.”

Lucky people “have an ability to turn their bad luck into good fortune” because of their resilience.

If you remove the sheen of self-help-book claptrap, there’s a kernel of something there.

Under this theory: Lucky people don’t believe in luck, or take whatever luck gives them, or they make their own luck. They give themselves maximum opportunities to get lucky. They give themselves outs. They watch for opportunity, and they seize it.

I basically buy that, mostly, as part of a package of ways one can usefully look at things. It is a version of the Zero Effect rules about looking for things – if you go looking for something specific, your chances of finding it are very bad, because of all the things in the world, you’re only looking for one of them. But if you go looking for anything at all, your chances of finding it are very good, because of all the things in the world, you’re bound to find some of them.

The part where positive expectations means things have an uncanny knack of coming true? That part is weirder. Confidence is an obvious factor. So is being convinced to try at all, and look for a way to actually make things happen, which is remarkably rare.

A lot of this feels to me like the type of advice that is true on average, and for most people on the margin. Of course, my readers are weird, so beware.

The most important words about luck might be Spider Murphy’s. Anything that looks sufficiently like consistent luck is not luck. Almost every time I went on an extended losing streak betting on sports, I was able to later figure out why it happened, and the answer was not ‘luck.’ DPS alone I actively think was luck, because it was front-loaded tournaments.

Then there’s a series of systematic losses in college basketball that I still don’t understand. I doubt the answer is luck.

Vastly more men than women play poker. Why?

The first obvious answer is straight up misogyny and poor treatment.

So what explains the poker gender gap? The explanations I’ve come across fall into roughly five categories. 1. There’s often openly abusive and misogynistic behavior toward women, made worse by a “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas” attitude. (2025)

“I’ve actually experienced the worst misogyny at the lowest stakes. Where people are there to have fun and they’re drinking and they feel like I’m cramping their style,” said Maria Konnikova.

However, I’ve also heard awful stories about misconduct coming from highly regarded high-stakes players—but the worst stories often come only once you’ve turned the tape recorder off. (2042)

Men struggle to make adult friendships, and poker provides a means for male social bonding that appeals to a broad cross section of men, but women aren’t always invited to the party. (2045)

Maria’s comment is interesting and the last one reinforces it. One can have a model that few women play poker, so men who prefer that choose to play poker in order to be in a male-dominated space and get a relaxed form of social interaction they can’t get elsewhere, which makes them treat women who do show up badly, perpetuating the cycle.

And I totally believe that there are plenty of awful misconduct stories out there.

Here are some other stories that make sense and probably contribute.

Men—whether through nurture, culture, or nature—tend on average to be more competitive and aggressive, essential attributes for success at poker. (2059)

Men have more financial and social capital to gamble with. (2072)

“Society doesn’t really encourage women from a young age to take risks. We’re taught growing up that we always have to be more responsible,” said Ho.

It’s an advantage to have the option of blending in, and that’s easier when you’re a white guy. (2086)

My note would be that it’s not so much that men ‘have what it takes to succeed’ in poker, in terms of competitiveness and aggression. It’s more that men more often ‘have what it takes to want to play’ and exhibit this type of competitiveness and aggression and social interaction.

All the other stuff matters a lot, and poker (like most other games) could and needs to do a much better job making women feel welcome and ensuring they have good experiences, but at the end of the day there has to be a reason everyone shows up for a zero-sum game. You have to want to do it enough to invest your time, it has to be rewarding. That’s going to skew the gender ratio.

Nate Silver spends a bunch of time on a cheating scandal at the Hustler Live game.

It was a fascinating situation, such that I’d already listened to half an hour of Doug Polk explaining the various arguments about it.

Essentially, there was this televised game. A player went all-in on a semi-bluff, and Lew made a hero call with J4 that made absolutely no sense. It was a +EV call in isolation if you knew exactly what cards her opponent had, but she couldn’t beat a huge percentage of even his bluffs. So it looks hella suspicious. But also, if you were going to cheat on a livestream, you would pick a much better spot that also was far less obvious.

What happened before is that there were several instances—both during that day’s taping, and on two previous episodes of Hustler Casino Live—where Lew would have benefited from cheating, but didn’t. Most cheaters aren’t like that. (2197)

But in nineteen hours of livestreamed hands across three sessions, there’s no hand other than J4 that looks like cheating—even after thousands of detail-obsessed poker players have scoured Lew’s footage for signs of impropriety. There’s also the fact that if Lew cheated, she picked an awfully bad spot for it. (2204)

I have a very strong intuition here as well. Cheaters do not do this. They do not have the patience or discipline. When they do, they pick better spots.

In conversations with Nate, Lew didn’t come across so well. Her surface story doesn’t add up, but that could be because she doesn’t want to admit she misread or misremembered her hand.

But my spidey sense was getting a weird vibe. At times, Lew looked out into space as though she was reading off a teleprompter. And Lew has a habit of relaying information that is either superfluous or doesn’t entirely check out. Two sources that I spoke with used the term “pathological liar” to describe Lew’s habit of tangling herself up in knots. (2123)

Ultimately, I don’t think one can know and neither does Nate.

I’m not saying this is the only theory—if I were handicapping, I’d still put the chance of cheating at 35 or 40 percent. (2222)

I would bet on the ‘no cheating’ side of that line, if I had to bet, but it seems very reasonable.

What’s remarkable is that for a long time poker players basically tolerated cheating.

Until the Poker Boom years, the prevailing attitude was often that a poker player would win by any means necessary. (2179)

Magic in its first few years was a lot like this as well. It was your job to defend yourself, if someone cheated you that was your fault. Then, in both cases, the act got cleaned up, and cheating become both rare and a good way to get exiled if people were convinced you did it.

The bigger lesson from this is actually about Adelstein, the player Lew won the hand against. There is no question Adelstein legitimately thinks that Lew cheated. But by throwing a fit over it, and insisting that she pay him back, while Adelstein won the battle – he got his refund, after also drawing live – he very much lost the war. He’d had a great game going with lots of +EV, and after this incident it is gone. Compare this to Brunson in his early days, who took being robbed in stride as part of the game.

That’s the thing about gambling. If you want to win big in cash games, you have to be good. But a lot of people are good. The rarer and more important skill is getting those who aren’t good to give you the action. Often that means ‘knowing what they are prepared to lose’ or otherwise ensuring they feel good about coming back. Other times, it means eating a loss, even if it isn’t fair.

You have to factor in everything, but only to the extent it deserves. It’s easy to either let most considerations go, or to weigh them all too close to equally, which are the human default settings.

In this case, Wesley bet huge into Dwan in a gigantic televised pot, and Dwan won by making a ‘hero call’ with a hand that would ordinarily not be good enough to catch bluffs. Dwan had enough different reasons to be suspicious he felt he had odds to call.

There were roughly twenty “data points” that factored into this decision, Dwan said. For instance, Dwan thought that Wesley—ordinarily a tight player—had come into the session with an “agenda that was a little bit less about winning money” and more about making plays that looked cool on TV.

Wesley had to be bluffing 25 percent of the time to make Dwan’s call correct; his read on Wesley’s mindset was tentative, but maybe that was enough to get him from 20 percent to 24. (Bluffing in a huge pot looks cool on TV.)

And maybe Wesley’s physical mannerisms—like how he put his chips in quickly on the river, sometimes a sign of weakness—got Dwan from 24 percent to 29.

That was enough: Dwan took his time, coolly sipping from a bottle of water, and put the chips in to win a $3.1 million pot. If this kind of thought process seems alien to you—well, sorry, but your application to the River has been declined. (4267)

This all seems obvious and natural to me, if you can actually be this precise. I am skeptical of the precision in spots like this, the idea that poker players can ‘feel’ tiny differences, but I do think the good ones (like Dwan, who is clearly very good) end up doing an excellent approximation.

Blackjack is not worth your time. Yes, you can count cards, but don’t.

The new semi-blackjack roguelike game Dungeons and Degenerate Gamblers is okay, maybe Tier 3, but for superfans only. 21 is a roughly 3-star (out of 5) movie.

If you want to do blackjack card counting anyway, Nate does have some advice.

After about an hour of practice with a computer simulation that dealt six blackjack hands at a time at a medium-fast clip, I could get the count right about 95 percent of the time. (2330)

Their single-deck blackjack game—which on a slow night they’ll let you play for as little as $15—has a house edge of just 0.18 percent, assuming you play perfect basic strategy. (2342)

Pro tip: look for games where blackjack pays out 3:2 (so you win $75 if you make blackjack on a $50 bet) rather than 6:5 (so you’d only win $60). (2347)

In Professional Blackjack, the card counter Stanford Wong estimates that his benchmark strategy, executed perfectly under relatively favorable conditions, will net you about 60 cents for every $100 you bet—meaning a player edge of just 0.6 percent. (2418)

That’s all pretty miserable, even when it goes well, and the casinos will not take kindly if they figure out you are doing it. He goes into more detail, but there are better things to do with your time and life. I don’t know basic strategy and don’t plan to learn it, let alone how to do a count.

My basic advice for a casino is that there is a poker room and a sportsbook.

There also could be restaurants or a buffet, and hotel rooms, perhaps a show or a conference or a nearby sporting event. Sure, why not. Have fun.

But that’s it. Everything else you can gamble on is a trap.

Table games are a small mistake, if you want to buy entertainment. If you want to do pure gambling at a table game like roulette or craps, go ahead I suppose, although I don’t know why you would want to, unless you are starting UPS and can’t make payroll without getting lucky, or otherwise actually benefit from making one big highly precise gamble – the fee they charge on that is not so unreasonable.

Nate’s explanation is that you play craps to be around others, bond, tell stories, ‘prove your bravery’ and such. Story value is a thing, I suppose, but I find this highly alien.

Blackjack we covered already. If you want to pure gamble and play basic strategy, I mean sure, house edge is small, go for it if that’s what you really want. I guess.

And there’s nothing wrong with using that to also get some house perks. And perhaps you can even engage in a little ‘light counting’ by playing normally, except walking away from the table if the count goes very negative, maybe go get lunch then. There’s not much they can do about that.

Slots, on the other hand? Huge mistake. Treat them like harmful illegal drugs. Avoid.

Slots, alas, are the real business of the casino.

Nevada casinos make roughly fifty bucks in profit from slots for every dollar they get out of the poker games they spread. (2451)

Nate mentions a great book, Addicted by Design, about slot machines, how they are designed and the toll they extract on people. These are the worst kinds of engineered Skinner boxes, with many slots players so far gone they do not even want to win, merely to have a ‘smooth ride down.’

And then there’s the part that casino executives don’t like to talk about. To some percentage of patrons, slots can be highly addictive—potentially three to four times faster at addicting players than card games or sports betting.

Even though the percentage of players who become problem gamblers is relatively small, these players may account for 30 to 60 percent of slot revenues because they play so often. I’m about to tell you what might be the most shocking thing that I learned in the course of writing this book.

It may seem counterintuitive at first, but it helps to explain why slot machines can trigger such compulsive behavior. Here goes: according to Schüll, many of the problem gamblers she met didn’t actually want to win. “This was the thing that I couldn’t really get for a while,” Schüll told me. “But…I kept hearing it over and over again.”

Why wouldn’t a gambler want to win? Well, when you win a slot jackpot, it’s a disruptive experience. Lights flash. Alarms ring. The other patrons ooh and ah. A smiling attendant comes by to check your ID and hand you a tax form. (2890)

Then operators realized, even if you exclude the truly addicted, almost no one playing slots cares about the payouts. They wouldn’t notice being cheated even more.

We determined that for the individual to recognize the difference between a slot machine that had a hold of five percent, and one that had a hold of eight percent, the player would have to make forty thousand handle pulls on each machine.”

Forty thousand spins is a lot. (2706)

In 1997, the year before Loveman joined Caesars, slot machines on the Las Vegas Strip had an average hold percentage of 5.67 percent. By the time he left in 2015, it had jumped to 7.77 percent, right where those Atlantic City numbers had been. (2715)

The assumption here is that someone would play slots without knowing the odds, assuming the slots were reasonable, and maybe eventually notice the odds were off. And yeah, by that standard, it is going to be a long, long time before you confidently notice the slots are too tight, especially when you factor in jackpots. If the person is even paying attention at all.

The good news is the casino isn’t allowed to rob you even more in real time. Odds changes have to go through the NGCB. But yes, that is how it works. They flat out never tell you the odds. My lord.

And unlike in blackjack, you can’t just look up the odds—they aren’t listed anywhere! In fact, the same machine can have different payouts in different parts of the casino, without any outward sign to the customer.

Besides, who says the customer even cares? If you have to ask what the payout is, well, guess what? It’s less than 100%. And, as with lotteries, the money rolls in.

On the Las Vegas Strip, slot machines represent only 29 percent of overall (gambling plus nongambling) revenues. At off-Strip casinos, they’re 53 percent. (2857)

Are there some people who get genuine entertainment out of slots? Are there retirees who have a better time with slots than they would without them? There are some, to be sure.

There are even a handful of advantage players out there on the slots, because occasionally machines will have progressive jackpots or other tricks that can make them +EV in unusual circumstances.

Ever since, I’ve always kept an eye out for advantage players. They’re not that hard to spot. Their posture is more erect. They have a purposefulness that the typical slot-playing tourist lacks. And they’re finding $20 bills that aren’t supposed to exist. Seeking Action—or Escape? It’s not literally true that every human society has had gambling. But it’s been very common, dating (2831)

The odds of this being you are not high. And it doesn’t sound like a great gig.

I’ve thus become rather radicalized on slot machines. I do think we should be allowed to have casinos, including games I would never play like roulette, craps or baccarat. Slots are different. I think they should be Considered Harmful, and banned.

If that means (as it likely does) a radically downsized casino industry? Your offer is acceptable. If it also means fewer available poker games? I’ll accept that too.

I have also always been strongly against allowing mobile casino games. Essentially forcing everyone to carry around, on their person, access to unlimited immediate gambling complete with push notifications and entrapping offers is going to lead to quite a lot of ruined lives, and it is not a reasonable position in which to put those prone to gambling problems.

Recently, based on the results of our grand experiments, I’ve also greatly soured on allowing mobile sports betting. I love sports betting when ‘used responsibly,’ but this is very clearly not that. Studies are showing dramatic declines in savings and creditworthiness, across the board, in places with mobile sports betting. I have a draft post going into the details, and they’re pretty terrible.

Meanwhile, we are not offering even responsible players a good experience, instead charging them high prices, and the ads and incentives are bleeding into all things sports in toxic fashion. With all the fees they have to pay in advertising and to credit cards and to the state, the operators feel they don’t have a choice, I get that. But c’mon.

I was watching a baseball game two days ago, and during the broadcast they noted an ‘in game parlay’ of Mets to win and Over 7.5, at odds of +105 (so bet 100 to win 105). Highlighting in-game parlays is bad enough. But the crazy part was that the score was 4-1, the Mets were at home (so likely no bottom of the ninth) and it was the middle of the seventh inning. They wanted you to go Over 2.5 runs in 2 innings, and not even win if the Red Sox rallied and won.

I happen to have a spreadsheet for things like this. I looked up the odds on the game and plugged in the situation. Even if you assume the Mets always win, the fair odds were about +237 (you bet 100 to win 237, 29.7% odds) for Over 7.5 on its own, plus Boston wins 10%+ of the time that those runs score (they win 5% of the time, and they can’t win without there being at Over 7.5 runs). Even Over 6.5, on its own, would have been a (slightly) bad bet at +105.

Highway robbery. This must end.

At first Las Vegas was ruled by the mob. You could not trust it.

Then Nevada realized that people would only flock to Vegas if it was clear they could trust it. So they cleaned up their act, for real. They passed a law making this clear.

NRS 463.0129 Public policy of state concerning gaming; license or approval revocable privilege. The Legislature hereby finds, and declares to be the public policy of this state, that: The gaming industry is vitally important to the economy of the State and the general welfare of the inhabitants.

The continued growth and success of gaming is dependent upon public confidence and trust…and that gaming is free from criminal and corruptive elements. Public confidence and trust can only be maintained by strict regulation of all persons, locations, practices, associations and activities related to the operation of licensed gaming establishments. (2533)

Nate translates that as:

Gambling is vital to Nevada

Public trust is vital to gambling

Getting rid of the mob is vital to public trust.

Las Vegas may have an anything-goes, libertarian, frontier spirit. But without these regulations, it would be nothing like what it is today.

To be clear, you’re very unlikely to be cheated by the house in an American casino today—they’ll take your money fair and square. But that’s because of statutes like NRS 463.0129.

In fact, it’s actually in the industry’s best interest to have stringent regulation. Why? Because of the prisoner’s dilemma. If my casino, the Silver Spike, starts removing aces from its blackjack decks—boosting profits for my shareholders but in a way that its customers find hard to detect—the optimal strategy for the Gold Nugget down the block is to reciprocate. (2545)

I wish certain other industries, in particular AI, understood this. You think you want an ‘anything goes’ world. Consider the possibility that you are very wrong, and what would happen if events cause the public to further lose trust.

So now we have casinos in Nevada we can trust, and largely also around the world. The standard was set.

The second part of the story is that at first there weren’t huge expensive ‘experience’ casinos. Then Wynn dared to build one, it worked, and that established the business model. So now everyone does these audacious Vegas projects, up to and including The Sphere, because they can (on a regulatory and financial level) and a good time is had by all, resulting in a three-level market.

Really, there isn’t just one casino business model—there are three (2574):

There is the high-end luxury resort business.

Then there is the largest segment of the market by revenue, an upper-middlebrow market, dominated by major corporations like MGM and Caesars.

Finally, there is the “locals market,” focused on tourists on a tight budget, retirees, and working-class and middle-class people who visit casinos mostly to do one thing: play slots. Not blackjack, and certainly not poker. Maybe a decent steak dinner purchased with casino comps. But mostly just slots.

As noted above, I think the ‘locals’ business model of slots should die in a fire.

The other two could presumably survive without the slots, and there could be a place for them.

The casino business works because, despite most of its customers leaving with less money than they came with, those customers come back.

Disneyworld is famous as a business case study because 70 percent of its first-time visitors eventually return. Well, typically about 80 percent of visitors to Las Vegas are repeat customers. (2741)

Yes, but those are not comparable statistics. So quick nerdsnipe math break.

If 70% of your first time visitors eventually return, then at most 59% of your customers can be first time visitors (if no one ever comes back a third time), but you don’t know what percentage repeat. If you end up with Power Users who come back every year it could be quite a lot.

Similarly, if 80% of your customers are repeat customers, that could be because 10% of your customers get hooked and come back every year for an average of 10 years, while the majority never return. It doesn’t sound so implausible.

My guess would be that the chance of another visit goes steadily up every time you visit Disneyworld. So let’s say that 70% of first timers return, then 80% of second-timers return, then 85% from there until someone stops. In that case, for every first time visit, you get about 6 (technically 5.993) revisits. That’s very impressive, and an 86% rate, beating Las Vegas. If it’s 70% all the way, then it’s only 77% repeat visits.

Either way, yes, Las Vegas is doing Disneyland-levels of repeat business.

The recent history of all things gaming and gambling is the history of the whale.

The old business model of selling everyone a fixed price experience? Old, also busted.

Customer value follows a power law. Your median customer is nice, but they do not have that much money that they come looking to spend. The extreme right tail of the curve, the true ‘whales’ that spend tons of money, and getting the most out of them, are where all the profit lies.

You still cater to your other customers. Without them, the whales won’t show up. You need to build a reputation. And you need the others in the background, to form a contrast and an ecosystem and allow your amenities to exist and to fill out your games and so on. What’s the point of being the big spender without lording it over the others and getting that edge? That’s a lot of what is for sale.

This, together with the expectation of baseline play for free, has ruined most of mobile gaming, and a lot of other computer gaming as well. Your experience can and will be made super toxic, exactly so that whales pay up to make it less so. You will lose, so that those who spend will win.

Anyway, welcome to the casino business. The customer is always right, and that customer is your big spender.

Some customers are spending hundreds or thousands of times more than others. “We would tell our folks that if you lose a Diamond customer, because of poor service, you have to find twenty Gold customers to replace them,” said Loveman. (2749)

The perks of having high status in a casino rewards program are almost unlimited. Officially, Caesars Seven Stars members get free or deeply discounted rooms at almost any Caesars property worldwide, thousands of dollars in dining and travel credits, and even a complimentary trip on a cruise ship.

Unofficially, their status can take them even further. VIPs often have personal hosts or concierges and can negotiate changes to game rules, substantial rebates if they lose, free food and drink from anywhere in the property, nights out at strip clubs, and even private jets. (2751)

If you’re a loser and you know it, clap your hands. Let’s negotiate. There are many casinos. There is only one you. So if you demand perks worth – and by worth we mean what they cost the casino, not what they’d cost for you to buy – half your expected losses, they should happily give them to you, if they think otherwise you would walk. Or if it means you play twice as often, or twice as high.

I remember an episode of the show Las Vegas where a big supposed whale comes to the casino, and gets the big expensive room and all the perks. But he doesn’t gamble. The host tells him his treatment comes with an expectation of play. He asks how much, puts that amount on the roulette wheel once, wins (of course, it’s fiction, and it’s enough that the casino is sweating that it might happen several more times), smiles and moves on.

Being a whale on purpose is not obviously a bad strategy, if you have the money to spend and enjoy the actual gambling parts or simply have TMM (too much money). You are buying the ultimate concierge service. The casino will go the extra mile to cater to you and your wishes and whims, and handle lots of super annoying logistics and other details for you. Claude estimated you can get maybe 20%-30% of your losses back in terms of casino costs. That doesn’t sound like much, but the markups are huge, and the connections and hookups are kind of free.

I have some experience with a whale coming in and being, from a net profits perspective, the main thing that matters for a while, being worth more than the rest of your business combined. It’s super weird, especially since you don’t know what is motivating the whale, how far you can push them, or what would cause the ride to end. Happily I was not in the perks department.

You think this is all unfair? Well, tough.

The notion of a customer who’s already paying for a luxury experience getting cut in line by someone who has even higher status strikes him the wrong way. When Wynn took his objections to Loveman, they agreed to disagree.

“I said to Gary, ‘Doesn’t that create an animosity? When these preferences are in full view? Doesn’t it make them a second-class citizen?’…And [Loveman] said, ‘On the contrary, Steve, it makes them aspirational.’

Loveman was probably right. (2767)

My hunch is this cuts both ways. It is absolutely aspirational, and it can also piss the mid-tier customer off if it becomes a practical issue. No one likes getting bumped. You are definitely lowering the quality of my product, and I will respond accordingly.

As I mentioned earlier, Trump is the clear indication that you can be in politics, and you can be doing River-related businesses like casinos, and still very clearly not have either the Village Nature or River Nature. Indeed, his abject failure to get along with either group is necessary for how the story played out.

If Trump is despised by the Village, he’s also not a member of the River. Yes, Trump might be competitive and risk-taking—and he can even have a contrarian streak, having correctly gambled in 2016 that he could repudiate John McCain, Mitt Romney, George W. Bush, and the rest of the Republican establishment and still win the party’s nomination.

But that alone doesn’t a Riverian make. He’s shown little of the capacity for abstract, analytical reasoning that distinguishes people in the River from those who undertake high-stakes but miscalculated −EV bets. (2642)

Trump at least was (he has lost some number of steps by now) very, very good at certain things. Those things proved highly valuable in 2016, especially in the primary, and previously in his television career.

They did not, however, serve him well when running a casino.

At properties like the Wynn in Las Vegas, things just tend to go smoothly most of the time. At the Trump Taj Mahal, they did not. Within a week of the opening, its slot machines mysteriously shut down. (2668)

Trump also borrowed money at extremely high interest rates to finance his casinos. Doing the math would have made it clear he was unlikely to be able to keep pace with the costs involved. And that is indeed what happened.

The other problem was that Atlantic City failed to deliver the goods.

Atlantic City also proved to be a poor bet. Its gambling revenues actually exceeded those in Las Vegas throughout most of the 1980s and early 1990s but then declined by more than half.

Why did Vegas prove to be so much more durable? Perhaps because Atlantic City bet on gambling, gambling, and more gambling rather than offering guests a well-rounded entertainment experience. (About 75 percent of the Taj’s gross revenues in 1990 were from the gaming floor.) It also has poor vibes.

Las Vegas presents you with the feeling of freedom—casinos spill into one another, the Strip is walkable, and the weather is pleasant for much of the year. AC is more of a walled city, with casinos as self-contained fortresses in a hollowed-out, high-crime city. (2673)

I’ve been to Las Vegas a number of times. It is not my kind of place, but I understand it and appreciate it. I appreciate its honesty and shamelessness, its willingness to come out and be itself and fully tacky and what it is, and say this is here for you if you want it. And to provide, in many ways, a high quality product that makes you feel like you’re enjoying aspects of the good life. The strip is fun, and yes I have jaywalked it.

The one time I went to Atlantic City, for a Magic Grand Prix, and had a chance to go out into the city a bit? Things were bleak. And by bleak I mean post-apocalyptic. It felt deserted, as dust filled the air. Finally I made my way to a casino and attempted to play a little poker. It wasn’t a good experience on any level, and I quickly left.

Most casinos are horrible places, by design.

The canonical book on casino design—Bill Friedman’s 629-page Designing Casinos to Dominate the Competition, published in 2000—laid out a series of principles that aggressively invert almost every tenet of modern architectural theory, advocating for a seemingly unpleasant environment for the patron.

“LOW CEILINGS beat HIGH CEILINGS,” reads one. “A COMPACT AND CONGESTED GAMBLING-EQUIPMENT LAYOUT beats A VACANT AND SPACIOUS FLOOR LAYOUT,” is another.