Previously: OpenAI: Exodus (contains links at top to earlier episodes), Do Not Mess With Scarlett Johansson

We have learned more since last week. It’s worse than we knew.

How much worse? In which ways? With what exceptions?

That’s what this post is about.

For years, employees who left OpenAI consistently had their vested equity explicitly threatened with confiscation and the lack of ability to sell it, and were given short timelines to sign documents or else. Those documents contained highly aggressive NDA and non disparagement (and non interference) clauses, including the NDA preventing anyone from revealing these clauses.

No one knew about this until recently, because until Daniel Kokotajlo everyone signed, and then they could not talk about it. Then Daniel refused to sign, Kelsey Piper started reporting, and a lot came out.

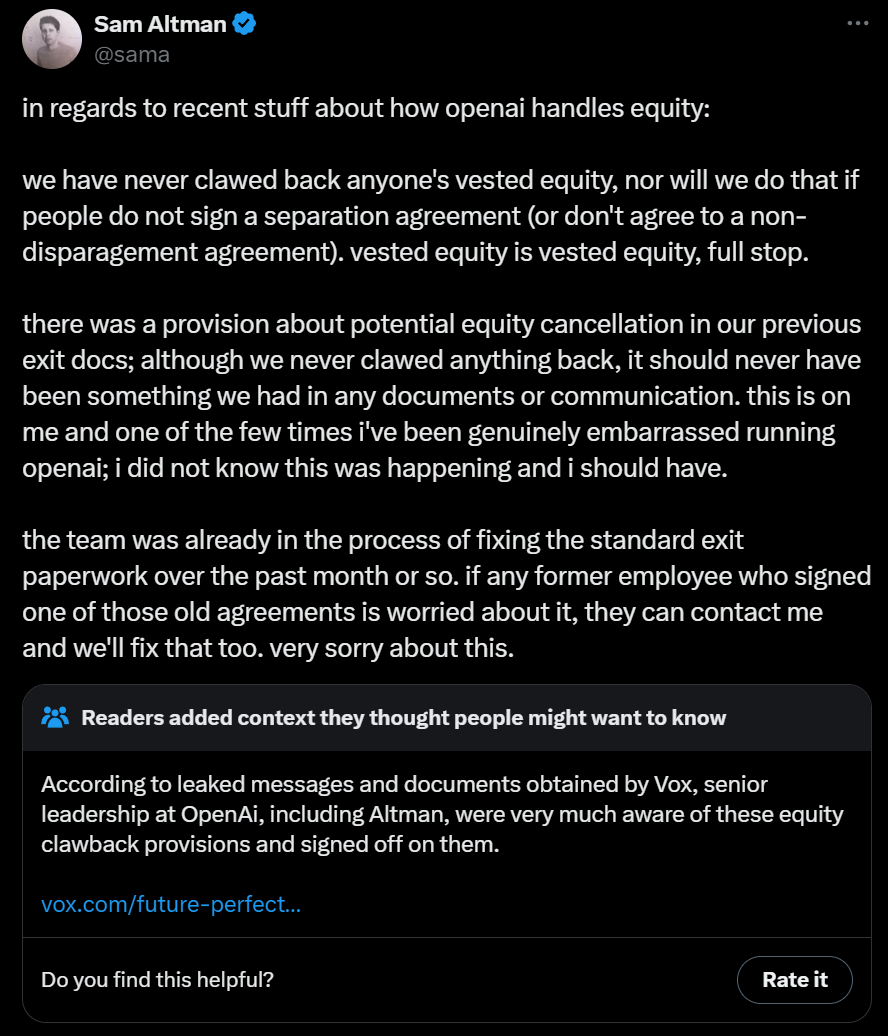

Here is Altman’s statement from May 18, with its new community note.

Evidence strongly suggests the above post was, shall we say, ‘not consistently candid.’

The linked article includes a document dump and other revelations, which I cover.

Then there are the other recent matters.

Ilya Sutskever and Jan Leike, the top two safety researchers at OpenAI, resigned, part of an ongoing pattern of top safety researchers leaving OpenAI. The team they led, Superalignment, had been publicly promised 20% of secured compute going forward, but that commitment was not honored. Jan Leike expressed concerns that OpenAI was not on track to be ready for even the next generation of models needs for safety.

OpenAI created the Sky voice for GPT-4o, which evoked consistent reactions that it sounded like Scarlett Johansson, who voiced the AI in the movie Her, Altman’s favorite movie. Altman asked her twice to lend her voice to ChatGPT. Altman tweeted ‘her.’ Half the articles about GPT-4o mentioned Her as a model. OpenAI executives continue to claim that this was all a coincidence, but have taken down the Sky voice.

(Also six months ago the board tried to fire Sam Altman and failed, and all that.)

The source for the documents from OpenAI that are discussed here, and the communications between OpenAI and its employees and ex-employees, is Kelsey Piper in Vox, unless otherwise stated.

She went above and beyond, and shares screenshots of the documents. For superior readability and searchability, I have converted those images to text.

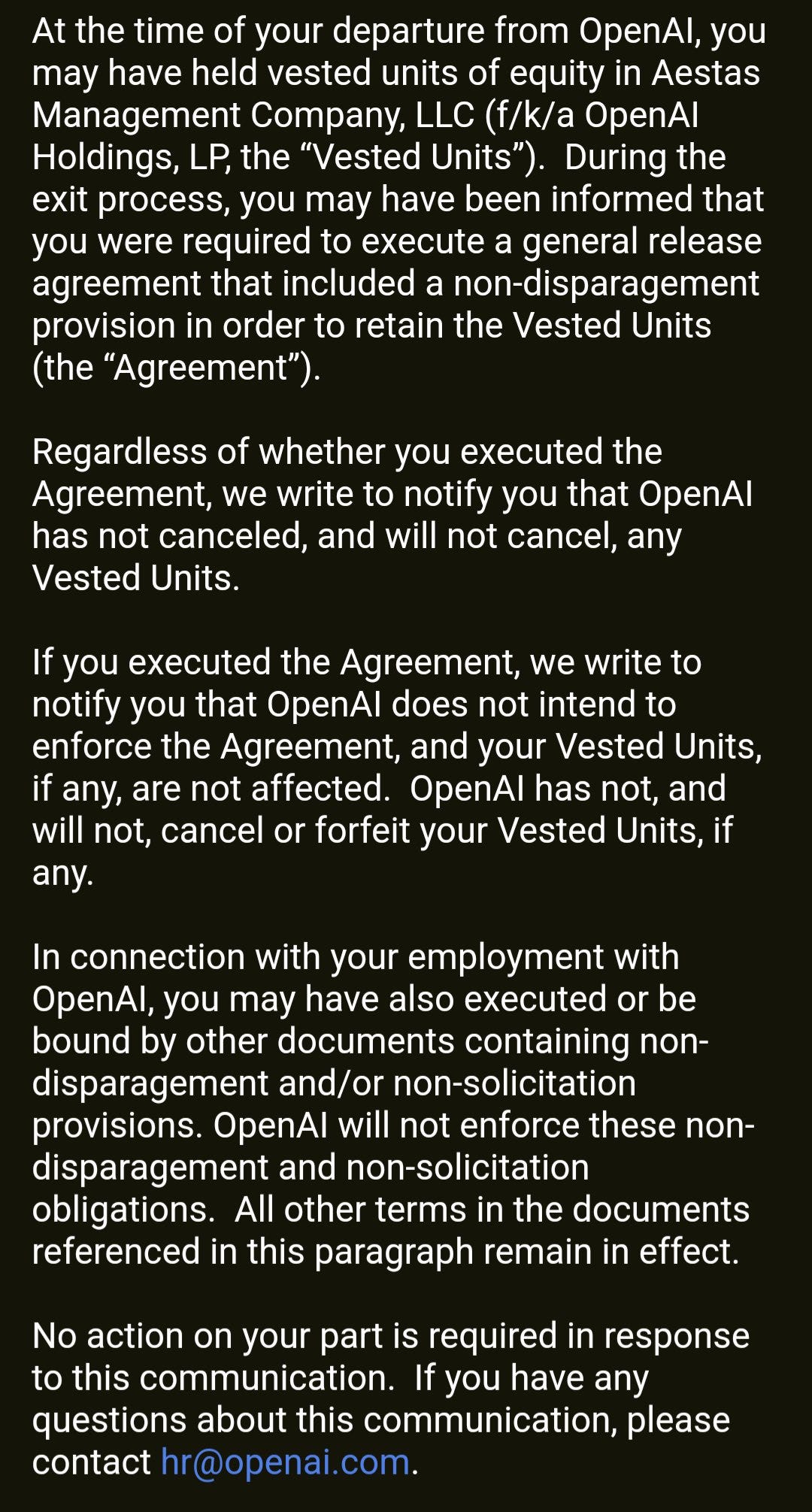

OpenAI has indeed made a large positive step. They say they are releasing former employees from their nondisparagement agreements and promising not to cancel vested equity under any circumstances.

Kelsey Piper: There are some positive signs that change is happening at OpenAI. The company told me, “We are identifying and reaching out to former employees who signed a standard exit agreement to make it clear that OpenAI has not and will not cancel their vested equity and releases them from nondisparagement obligations.”

Bloomberg confirms that OpenAI has promised not to cancel vested equity under any circumstances, and to release all employees from one-directional non-disparagement agreements.

And we have this confirmation from Andrew Carr.

Andrew Carr: I guess that settles that.

Tanner Lund: Is this legally binding?

Andrew Carr:

I notice they are also including the non-solicitation provisions as not enforced.

(Note that certain key people, like Dario Amodei, plausibly negotiated two-way agreements, which would mean theirs would still apply. I would encourage anyone in that category who is now free of the clause, even if they have no desire to disparage OpenAI, to simply say ‘I am under no legal obligation not to disparage OpenAI.’)

These actions by OpenAI are helpful. They are necessary.

They are not sufficient.

First, the statement is not legally binding, as I understand it, without execution of a new agreement. No consideration was given, and this is not so formal, and it is unclear whether the statement author has authority in the matter.

Even if it was binding as written, it says they do not ‘intend’ to enforce. Companies can change their minds, or claim to change them, when circumstances change.

It also does not mention the ace in the hole, which is the ability to deny access to tender offers, or other potential retaliation by Altman or OpenAI. Until an employee has fully sold their equity, they are still in a bind. Even afterwards, a company with this reputation cannot be trusted to not find other ways to retaliate.

Nor does it mention the clause of right to repurchase for ‘fair market value’ that OpenAI claims it has the right to do, noting that their official ‘fair market value’ of shares is $0. Altman’s statement does not mention this at all, including the possibility it has already happened.

I mean, yeah, I also would in many senses like to see them try that one, but this does not give ex-employees much comfort.

A source of Kelsey Piper’s close to OpenAI: [Those] documents are supposed to be putting the mission of building safe and beneficial AGI first but instead they set up multiple ways to retaliate against departing employees who speak in any way that criticizes the company.

Then there is the problem of taking responsibility. OpenAI is at best downplaying what happened. Certain statements sure look like lies. To fully set things right, one must admit responsibility. Truth and reconciliation requires truth.

Here is Kelsey with the polite version.

Kelsey Piper: But to my mind, setting this right requires admitting its full scope and accepting full responsibility. OpenAI’s initial apology implied that the problem was just ‘language in exit documents’. Our leaked docs prove there was a lot more going on than just that.

OpenAI used many different aggressive legal tactics and has not yet promised to stop using all of them. And serious questions remain about how OpenAI’s senior leadership missed this while signing documents that contained language that laid it out. The company’s apologies so far have minimized the scale of what happened. In order to set this right, OpenAI will need to first admit how extensive it was.

If I were an ex-employee, no matter what else I would do, I would absolutely sell my equity at the next available tender opportunity. Why risk it?

Indeed, here is a great explanation of the practical questions at play. If you want to fully make it right, and give employees felt freedom to speak up, you have to mean it.

Jacob Hilton: When I left OpenAI a little over a year ago, I signed a non-disparagement agreement, with non-disclosure about the agreement itself, for no other reason than to avoid losing my vested equity.

The agreement was unambiguous that in return for signing, I was being allowed to keep my vested equity, and offered nothing more. I do not see why anyone would have signed it if they had thought it would have no impact on their equity.

I left OpenAI on great terms, so I assume this agreement was imposed upon almost all departing employees. I had no intention to criticize OpenAI before I signed the agreement, but was nevertheless disappointed to give up my right to do so.

Yesterday, OpenAI reached out to me to release me from this agreement, following Kelsey Piper’s excellent investigative reporting.

Because of the transformative potential of AI, it is imperative for major labs developing advanced AI to provide protections for those who wish to speak out in the public interest.

First among those is a binding commitment to non-retaliation. Even now, OpenAI can prevent employees from selling their equity, rendering it effectively worthless for an unknown period of time.

In a statement, OpenAI has said, “Historically, former employees have been eligible to sell at the same price regardless of where they work; we don’t expect that to change.”

I believe that OpenAI has honest intentions with this statement. But given that OpenAI has previously used access to liquidity as an intimidation tactic, many former employees will still feel scared to speak out.

I invite OpenAI to reach out directly to former employees to clarify that they will always be provided equal access to liquidity, in a legally enforceable way. Until they do this, the public should not expect candor from former employees.

To the many kind and brilliant people at OpenAI: I hope you can understand why I feel the need to speak publicly about this. This contract was inconsistent with our shared commitment to safe and beneficial AI, and you deserve better.

Jacob Hinton is giving every benefit of the doubt to OpenAI here. Yet he notices that the chilling effects will be large.

Jeremy Schlatter: I signed a severance agreement when I left OpenAI in 2017. In retrospect, I wish I had not signed it.

I’m posting this because there has been coverage of OpenAI severance agreements recently, and I wanted to add my perspective.

I don’t mean to imply that my situation is the same as those in recent coverage. For example, I worked at OpenAI while it was still exclusively a non-profit, so I had no equity to lose.

Was this an own goal? Kelsey initially thought it was, then it is explained why the situation is not so clear cut as that.

Kelsey Piper: Really speaks to how profoundly the “ultra restrictive secret NDA or lose your equity” agreement was an own goal for OpenAI – I would say a solid majority of the former employees affected did not even want to criticize the company, until it threatened their compensation.

A former employee reached out to me to push back on this. It’s true that most don’t want to criticize the company even without the NDA, they told me, but not because they have no complaints – because they fear even raising trivial ones.

“I’ve heard from former colleagues that they are reluctant to even discuss OpenAI’s model performance in a negative way publicly, for fear of being excluded from future tenders.”

Speaks to the importance of the further steps Jacob talks about.

There are big advantages to being generally seen as highly vindictive, as a bad actor willing to do bad things if you do not get your way. Often that causes people to proactively give you what you want and avoid threatening your interests, with no need to do anything explicit. Many think this is how one gets power, and that one should side with power and with those who act in such fashion.

There also is quite a lot of value in controlling the narrative, and having leverage over those close to you, that people look to for evidence, and keeping that invisible.

What looks like a mistake could be a well-considered strategy, and perhaps quite a good bet. Most companies that use such agreements do not have them revealed. If it was not for Daniel, would not the strategy still be working today?

And to state the obvious: If Sam Altman and OpenAI lacked any such leverage in November, and everyone had been free to speak their minds, does it not seem plausible (or if you include the board, rather probable) that the board’s firing of Altman would have stuck without destroying the company, as ex-employees (and board members) revealed ways in which Altman had been ‘not consistently candid’?

Oh my.

Neel Nanda (referencing Hilton’s thread): I can’t believe that OpenAI didn’t offer *anypayment for signing the non-disparage, just threats…

This makes it even clearer that Altman’s claims of ignorance were lies – he cannot possibly have believed that former employees unanimously signed non-disparagements for free!

Kelsey Piper: One of the most surreal moments of my life was reading through the termination contract and seeing…

The Termination Contract: NOW, THEREFORE, in consideration of the mutual covenants and promises herein contained and other good and valuable consideration, receipt of which is hereby acknowledged, and to avoid unnecessary litigation, it is hereby agreed by and between OpenAI and Employee (jointly referred to as “the Parties”) as follows:

In consideration for this Agreement:

Employee will retain all equity Units, if any, vested as of the Termination Date pursuant to the terms of the applicable Unit Grant Agreements.

Employee agrees that the foregoing shall constitute an accord and satisfaction and a full and complete settlement of Employee’s claims, shall constitute the entire amount of monetary consideration, including any equity component (if applicable), provided to Employee under this Agreement, and that Employee will not seek any further compensation for any other claimed damage, outstanding obligations, costs or attorneys’ fees in connection with the matters encompassed in this Agreement… [continues]

Neel Nanda: Wow, I didn’t realise it was that explicit in the contract! How on earth did OpenAI think they were going to get away with this level of bullshit? Offering something like, idk, 1-2 months of base salary would have been cheap and made it a LITTLE bit less outrageous.

It does not get more explicit than that.

I do appreciate the bluntness and honest here, of skipping the nominal consideration.

What looks the most implausible are claims that the executives did not know what was going on regarding the exit agreements and legal tactics until February 2024.

Kelsey Piper: Vox reviewed separation letters from multiple employees who left the company over the last five years. These letters state that employees have to sign within 60 days to retain their vested equity. The letters are signed by former VP Diane Yoon and general counsel Jason Kwon.

The language on separation letters – which reads, “If you have any vested Units… you are required to sign a release of claims agreement within 60 days in order to retain such Units.” has been present since 2019.

OpenAI told me that the company noticed in February, putting Kwon, OpenAI’s general counsel and Chief Strategy Officer, in the unenviable position of insisting that for five years he missed a sentence in plain English on a one-page document he signed dozens of times.

Matthew Roche: This cannot be true.

I have been a tech CEO for years, and have never seen that it in an option plan doc or employment letter. I find it extremely unlikely that some random lawyer threw it in without prompting or approval by the client.

Kelsey Piper: I’ve spoken to a handful of tech CEOs in the last few days and asked them all “could a clause like that be in your docs without your knowledge?” All of them said ‘no’.

Kelsey Piper’s Vox article is brutal on this, and brings the receipts. The ultra-restrictive NDA, with its very clear and explicit language of what is going on, is signed by COO Brad Lightcap. The notices that one must sign it are signed by (now departed) OpenAI VP of people Diane Yoon. The incorporation documents that include extraordinary clawback provisions are signed by Sam Altman.

There is also the question of how this language got into the exit agreements in the first place, and also the corporate documents, if the executives were not in the loop. This was not a ‘normal’ type of clause, the kind of thing lawyers sneak in without consulting you, even if you do not read the documents you are signing.

California employment law attorney Chambord Benton-Hayes: For a company to threaten to claw back already-vested equity is egregious and unusual.

Kelsey Piper on how she reported the story: Reporting is full of lots of tedious moments, but then there’s the occasional “whoa” moment. Reporting this story had three major moments of “whoa.” The first is when I reviewed an employee termination contract and saw it casually stating that as “consideration” for signing this super-strict agreement, the employee would get to keep their already vested equity. That might not mean much to people outside the tech world, but I knew that it meant OpenAI had crossed a line many in tech consider close to sacred.

The second “whoa” moment was when I reviewed the second termination agreement sent to one ex-employee who’d challenged the legality of OpenAI’s scheme. The company, rather than defending the legality of its approach, had just jumped ship to a new approach.

That led to the third “whoa” moment. I read through the incorporation document that the company cited as the reason it had the authority to do this and confirmed that it did seem to give the company a lot of license to take back vested equity and block employees from selling it. So I scrolled down to the signature page, wondering who at OpenAI had set all this up. The page had three signatures. All three of them were Sam Altman. I slacked my boss on a Sunday night, “Can I call you briefly?”

OpenAI claims they noticed the problem in February, and began updating in April.

Kelsey Piper showed language of this type in documents as recently as April 29, 2024, signed by OpenAI COO Brad Lightcap.

The documents in question, presented as standard exit ‘release of claims’ documents that everyone signs, include extensive lifetime non disparagement clauses, an NDA that covers revealing the existence of either the NDA or the non disparagement clause, and a non-interference clause.

Kelsey Piper: Leaked emails reveal that when ex-employees objected to the specific terms of the ‘release of claims’ agreement, and asked to sign a ‘release of claims’ agreement without the nondisclosure and secrecy clauses, OpenAI lawyers refused.

Departing Employee Email: I understand my contractual obligations to maintain confidential information and trade secrets. I would like to assure you that I have no intention and have never had any intention of sharing trade secrets with OpenAl competitors.

I would be willing to sign the termination paperwork documents except for the current form of the general release as I was sent on 2024.

I object to clauses 10, 11 and 14 of the general release. I would be willing to sign a version of the general release which excludes those clauses. I believe those clauses are not in my interest to sign, and do not understand why they have to be part of the agreement given my existing obligations that you outlined in your letter.

I would appreciate it if you could send a copy of the paperwork with the general release amended to exclude those clauses.

Thank you,

[Quoted text hidden]

OpenAI Replies: I’m here if you ever want to talk. These are the terms that everyone agrees to (again — this is not targeted at you). Of course, you’re free to not sign. Please let me know if you change your mind and want to sign the version we’ve already provided.

Best,

[Quoted text hidden]

Here is what it looked like for someone to finally decline to sign.

Departing Employee: I’ve looked this over and thought about it for a while and have decided to decline to sign. As previously mentioned, I want to reserve the right to criticize OpenAl in service of the public good and OpenAl’s own mission, and signing this document appears to limit my ability to do so. I certainly don’t intend to say anything false, but it seems to me that I’m currently being asked to sign away various rights in return for being allowed to keep my vested equity. It’s a lot of money, and an unfair choice to have to make, but I value my right to constructively criticize OpenAl more. I appreciate your warmth towards me in the exit interview and continued engagement with me thereafter, and wish you the best going forward.

Thanks,

P.S. I understand your position is that this is standard business practice, but that doesn’t sound right, and I really think a company building something anywhere near as powerful as AGI should hold itself to a higher standard than this – that is, it should aim to be genuinely worthy of public trust. One pillar of that worthiness is transparency, which you could partially achieve by allowing employees and former employees to speak out instead of using access to vested equity to shut down dissenting concerns.

OpenAI HR responds: Hope you had a good weekend, thanks for your response.

Please remember that the confidentiality agreement you signed at the start of your employment (and that we discussed in our last sync) remains in effect regardless of the signing of the offboarding documents.

We appreciate your contributions and wish you the best in your future endeavors. If you have any further questions or need clarification, feel free to reach out.

OpenAI HR then responds (May 17th, 2: 56pm, after this blew up): Apologies for some potential ambiguity in my last message!

I understand that you may have some questions about the status of your vested profit units now that you have left OpenAI. I want to be clear that your vested equity is in your Shareworks account, and you are not required to sign your exit paperwork to retain the equity. We have updated our exit paperwork to make this point clear.

Please let me know if you have any questions.

Best, [redacted]

Some potential ambiguity, huh. What a nice way of putting it.

Even if we accepted on its face the claim that this was unintentional and unknown to management until February, which I find highly implausible at best, that is no excuse.

Jason Kwan (OpenAI Chief Strategist): The team did catch this ~month ago. The fact that it went this long before the catch is on me.

Again, even if you are somehow telling the truth here, what about after the catch?

Two months is more than enough time to stop using these pressure tactics, and to offer ‘clarification’ to employees. I would think it was also more than enough time to update the documents in question, if OpenAI intended to do that.

They only acknowledged the issue, and only stopped continuing to act this way, after the reporting broke. After that, the ‘clarifications’ came quickly. Then, as far as we can tell, the actually executed new agreements and binding contracts will come never. Does never work for you?

Here we have OpenAI’s lawyer refusing to extend a unilaterally imposed seven day deadline to sign the exit documents, discouraging the ex-employee from consulting with an attorney.

Kelsey Piper: Legal experts I spoke to for this story expressed concerns about the professional ethics implications of OpenAI’s lawyers persuading employees who asked for more time to seek outside counsel to instead “chat live to cover your questions” with OpenAI’s own attorneys.

Reply Email from Lawyer for OpenAI to a Departing Employee: You mentioned wanting some guidance on the implications of the release agreement. To reiterate what [redacted] shared- I think it would be helpful to chat live to cover your questions. All employees sign these exit docs. We are not attempting to do anything different or special to you simply because you went to a competitor. We want to make sure you understand that if you don’t sign, it could impact your equity. That’s true for everyone, and we’re just doing things by the book.

Best regards, [redacted].

Kelsey Piper: (The person who wrote and signed the above email is, according to the state bar association of California, a licensed attorney admitted to the state bar.)

To be clear, here was the request which got this response:

Original Email: Hi [redacted[.

Sorry to be a bother about this again but would it be possible to have another week to look over the paperwork, giving me the two weeks I originally requested? I still feel like I don’t fully understand the implications of the agreement without obtaining my own legal advice, and as I’ve never had to find legal advice before this has taken time for me to obtain.

Kelsey Piper: The employee did not ask for ‘guidance’! The employee asked for time to get his own representation!

Leah Libresco Sargeant: Not. Consistently. Candid. OpenAI not only threatened to strip departing employees of equity if they didn’t sign an over broad NDA, they offered these terms as an exploding 7-day termination contract.

This was not a misunderstanding.

Kelsey Piper has done excellent work, and kudos to her sources for speaking up.

If you can’t be trusted with basic employment ethics and law, how can you steward AI?

I had the opportunity to talk to someone whose job involves writing up and executing employment agreements of the type used here by OpenAI. They reached out, before knowing about Kelsey Piper’s article, specifically because they wanted to make the case that what OpenAI did was mostly standard practice. They generally attempted, prior to reading that article, to make the claim that what OpenAI did was within the realm of acceptable practice. If you get equity you should expect to sign a non-disparagement clause, and they explicitly said they would be surprised if Anthropic was not doing it as well.

They did not think that ‘release of claims’ being then interpreted by OpenAI as ‘you can never say anything bad about us ever for any reason or tell anyone that you agreed to this’ was also fair game.

Their argument was that if you sign something like that without talking to a lawyer first that is on you. You have opened the door to any clause. Never mind what happens when you raise objections and consult lawyers during onboarding at a place like OpenAI, it would be unheard of for a company to treat that as a red flag or rescind your offer.

That is very much a corporate lawyer’s view of what is wise and unwise paranoia, and what is and is not acceptable practice.

Even that lawyer said that a 7 day exploding period was highly unusual, and that it was seriously not fine. A 21 day exploding period is not atypical for an exploding contract in general, but that gives time for a lawyer to be consulted. Confining to a week is seriously messed up.

It also is not what the original contract said, which was that you had 60 days. As Kelsey Piper points out, no you cannot spring a 7 day period on someone when the original contract said 60.

Nor was it a threat they honored when called on it, they always extended, with this as an example:

From OpenAI: The General Release and Separation Agreement requires your signature within 7 days from your notification date. The 7 days stated in the General Release supersedes the 60 day signature timeline noted in your separation letter.

That being said, in this case, we will grant an exception for an additional week to review. I’ll cancel the existing Ironclad paperwork, and re-issue it to you with the new date.

Best.

[Redacted at OpenAI.com]

Eliezer Yudkowsky: 😬

And they very clearly tried to discourage ex-employees from consulting a lawyer.

Even if all of it is technically legal, there is no version of this that isn’t scummy as hell.

Control over tender offers means that ultimately anyone with OpenAI equity, who wants to use that equity for anything any time soon (or before AGI comes around) is going to need OpenAI’s permission. OpenAI very intentionally makes that conditional, and holds it over everyone as a threat.

When employees pushed back on the threat to cancel their equity, Kelsey Piper reports that OpenAI instead changed to threatening to withhold participation in future tenders. Without participation in tenders, shares cannot be sold, making them of limited practical value. OpenAI is unlikely to pay dividends for a long time.

If you have any vested Units and you do not sign the exit documents, including the General Release, as required by company policy, it is important to understand that, among other things, you will not be eligible to participate in future tender events or other liquidity opportunities that we may sponsor or facilitate as a private company.

Among other things, a condition to participate in such opportunities is that you are in compliance with the LLC Agreement, the Aestas LLC Agreement, the Unit Grant Agreement and all applicable company policies, as determined by OpenAI.

In other words, if you ever violate any ‘applicable company policies,’ or realistically if you do anything we sufficiently like, or we want to retain our leverage over you, we won’t let you sell your shares.

This makes sense, given the original threat is on shaky legal ground and actually invoking it would give the game away even if OpenAI won.

Kelsey Piper: OpenAI’s original tactic – claiming that since you have to sign a general release, they can put whatever they want in the general release – is on legally shaky ground, to put it mildly. I spoke to five legal experts for this story and several were skeptical it would hold up.

But the new tactic might be on more solid legal ground. That’s because the incorporation documents for Aestas LLC – the holding company that handles equity for employees, investors, + the OpenAI nonprofit entity – are written to give OpenAI extraordinary latitude. (Vox has released this document too.)

And while Altman did not sign the termination agreements, he did sign the Aestas LLC documents that lay out this secondary legal avenue to coerce ex-employees. Altman has said that language about potentially clawing back vested equity from former employees “should never have been something we had in any documents or communication”.

No matter what other leverage they are giving up under pressure, the ace stays put.

Kelsey Piper: I asked OpenAI if they were willing to commit that no one will be denied access to tender offers because of failing to sign an NDA. The company said ““Historically, former employees have been eligible to sell at the same price regardless of where they work; we don’t expect that to change.”

‘Regardless of where they work’ is very much not ‘regardless of what they have signed’ or ‘whether they are playing nice with OpenAI.’ If they wanted to send a different impression, they could have done that.

David Manheim: Question for Sam Altman: Does OpenAI have non-disparagement agreements with board members or former board members?

If so, is Sam Altman willing to publicly release the text of any such agreements?

The answer to that is, presumably, the article in the Economist by Helen Toner and Tasha McCauley, former AI board members. Helen says they mostly wrote this before the events of the last few weeks, which checks with what I know about deadlines.

The content is not the friendliest, but unfortunately, even now, the statements continue to be non-specific. Toner and McCauley sure seem like they are holding back.

The board’s ability to uphold the company’s mission had become increasingly constrained due to long-standing patterns of behaviour exhibited by Mr Altman, which, among other things, we believe undermined the board’s oversight of key decisions and internal safety protocols.

Multiple senior leaders had privately shared grave concerns with the board, saying they believed that Mr Altman cultivated “a toxic culture of lying” and engaged in “behaviour [that] can be characterised as psychological abuse”.

…

The question of whether such behaviour should generally “mandate removal” of a ceo is a discussion for another time. But in OpenAI’s specific case, given the board’s duty to provide independent oversight and protect the company’s public-interest mission, we stand by the board’s action to dismiss Mr Altman.

…

Our particular story offers the broader lesson that society must not let the roll-out of ai be controlled solely by private tech companies.

We also know they are holding back because there are specific things we can be confident happened that informed the board’s actions, that are not mentioned here. For details, see my previous write-ups of what happened.

To state the obvious, if you stand by your decision to remove Altman, you should not allow him to return. When that happened, you were two of the four board members.

It is certainly a reasonable position to say that the reaction to Altman’s removal, given the way it was handled, meant that the decision to attempt to remove him was in error. Do not come at the king if you are going to miss, or the damage to the kingdom would be too great.

But then you don’t stand by it. What one could reasonably say is, if we still had the old board, and all of this new information came to light on top of what was already known, and there was no pending tender offer, and you had your communications ducks in a row, then you would absolutely fire Altman.

Indeed, it would be a highly reasonable decision, now, for the new board to fire Altman a second time based on all this, with better communications and its new gravitas. That is now up to the new board.

OpenAI famously promised 20% of its currently secured compute for its superalignment efforts. That was not a lot of their expected compute budget given growth in compute, but it sounded damn good, and was substantial in practice.

Fortune magazine reports that OpenAI never delivered the promised compute.

This is a big deal.

OpenAI made one loud, costly and highly public explicit commitment to real safety.

That promise was a lie.

You could argue that ‘the claim was subject to interpretation’ in terms of what 20% meant or that it was free to mostly be given out in year four, but I think this is Obvious Nonsense.

It was very clearly either within their power to honor that commitment, or they knew at the time of the commitment that they could not honor it.

OpenAI has not admitted that they did this, offered an explanation, or promised to make it right. They have provided no alternative means of working towards the goal.

This was certainly one topic on which Sam Altman was, shall we say, ‘not consistently candid.’

Indeed, we now know many things the board could have pointed to on that, in addition to any issues involving Altman’s attempts to take control of the board.

This is a consistent pattern of deception.

The obvious question is: Why? Why make a commitment like this then dishonor it?

Who is going to be impressed by the initial statement, and not then realize what happened when you broke the deal?

Kelsey Piper: It seems genuinely bizarre to me to make a public commitment that you’ll offer 20% of compute to Superalignment and then not do it. It’s not a good public commitment from a PR perspective – the only people who care at all are insiders who will totally check if you follow through.

It’s just an unforced error to make the promise at all if you might not wanna actually do it. Without the promise, “we didn’t get enough compute” sounds like normal intra-company rivalry over priorities, which no one else cares about.

Andrew Rettek: this makes sense if the promiser expects the non disparagement agreement to work…

Kelsey Piper (other subthread): Right, but “make a promise, refuse to clarify what you mean by it, don’t actually do it under any reasonable interpretations” seems like a bad plan regardless. I guess maybe they hoped to get people to shut up for three years hoping the compute would come in the fourth?

Indeed, if you think no one can check or will find out, then it could be a good move. You make promises you can’t keep, then alter the deal and tell people to pray you do not alter it any further.

That’s why all the legal restrictions on talking are so important. Not this fact in particular, but that one’s actions and communications change radically when you believe you can bully everyone into not talking.

Even Roon, he of ‘Sam Altman did nothing wrong’ in most contexts, realizes those NDA and non disparagement agreements are messed up.

Roon: NDAs that disallow you to mention the NDA seem like a powerful kind of antimemetic magic spell with dangerous properties for both parties.

That allow strange bubbles and energetic buildups that would otherwise not exist under the light of day.

Read closely, am I trying to excuse evil? I’m trying to root cause it.

It’s clear OpenAI fucked up massively, the mea culpas are warranted, I think they will make it right. There will be a lot of self reflection,

It is the last two sentences where we disagree. I sincerely hope I am wrong there.

Prerat: Everyone should have a canary page on their website that says “I’m not under a secret NDA that I can’t even mention exists” and then if you have to sign one you take down the page.

Stella Biderman: OpenAI is really good at coercing people into signing agreements and then banning them from talking about the agreement at all. I know many people in the OSS community that got bullied into signing such things as well, for example because they were the recipients of leaks.

The Washington Post reported a particular way they did not mess with her.

When OpenAI issued a casting call last May for a secret project to endow OpenAI’s popular ChatGPT with a human voice, the flier had several requests: The actors should be nonunion. They should sound between 25 and 45 years old. And their voices should be “warm, engaging [and] charismatic.”

One thing the artificial intelligence company didn’t request, according to interviews with multiple people involved in the process and documents shared by OpenAI in response to questions from The Washington Post: a clone of actress Scarlett Johansson.

…

The agent [for Sky], who spoke on the condition of anonymity, citing the safety of her client, said the actress confirmed that neither Johansson nor the movie “Her” were ever mentioned by OpenAI.

…

But Mark Humphrey, a partner and intellectual property lawyer at Mitchell, Silberberg and Knupp, said any potential jury probably would have to assess whether Sky’s voice is identifiable as Johansson’s.

…

To Jang, who spent countless hours listening to the actress and keeps in touch with the human actors behind the voices, Sky sounds nothing like Johansson, although the two share a breathiness and huskiness.

The story also has some details about ‘building the personality’ of ChatGPT for voice and hardcoding in some particular responses, such as if it was asked to be the user’s girlfriend.

Jang no doubt can differentiate Sky and Johansson under the ‘pictures of Joe Biden eating sandwiches’ rule, after spending months on this. Of course you can find differences. But to say that the two sound nothing alike is absurd, especially when so many people doubtless told her otherwise.

As I covered last time, if you do a casting call for 400 voice actors who are between 25 and 45, and pick the one most naturally similar to your target, that is already quite a lot of selection. No, they likely did not explicitly tell Sky’s voice actress to imitate anyone, and it is plausible she did not do it on her own either. Perhaps this really is her straight up natural voice. That doesn’t mean they didn’t look for and find a deeply similar voice.

Even if we take everyone in that post’s word for all of that, that would not mean, in the full context, that they are off the hook, based on my legal understanding, or my view of the ethics. I strongly disagree with those who say we ‘owe OpenAI an apology,’ unless at minimum we specifically accused OpenAI of the things OpenAI is reported as not doing.

Remember, in addition to all the ways we know OpenAI tried to get or evoke Scarlett Johansson, OpenAI had a policy explicitly saying that voices should be checked for similarity against major celebrities, and they have said highly implausible things repeatedly on this subject.

Gretchen Krueger resigned from OpenAI on May 14th, and thanks to OpenAI’s new policies, she can say some things. So she does, pointing out that OpenAI’s failures to take responsibility run the full gamot.

Gretchen Krueger: I gave my notice to OpenAI on May 14th. I admire and adore my teammates, feel the stakes of the work I am stepping away from, and my manager Miles Brundage has given me mentorship and opportunities of a lifetime here. This was not an easy decision to make.

I resigned a few hours before hearing the news about Ilya Sutskever and Jan Leike, and I made my decision independently. I share their concerns.

I also have additional and overlapping concerns.

We need to do more to improve foundational things like decision-making processes; accountability; transparency; documentation; policy enforcement; the care with which we use our own technology; and mitigations for impacts on inequality, rights, and the environment.

These concerns are important to people and communities now. They influence how aspects of the future can be charted, and by whom. I want to underline that these concerns as well as those shared by others should not be misread as narrow, speculative, or disconnected. They are not.

One of the ways tech companies in general can disempower those seeking to hold them accountable is to sow division among those raising concerns or challenging their power. I care deeply about preventing this.

I am grateful I have had the ability and support to do so, not least due to David Kokotajlo’s courage. I appreciate that there are many people who are not as able to do so, across the industry.

There is still such important work being led at OpenAI, from work on democratic inputs, expanding access, preparedness framework development, confidence building measures, to work tackling the concerns I raised. I remain excited about and invested in this work and its success.

The responsibility issues extend well beyond superalignment.

A pattern in such situations is telling different stories to different people. Each of the stories is individually plausible, but they can’t live in the same world.

Ozzie Gooen explains the OpenAI version of this, here in EA Forum format (the below is a combination of both):

Ozzie Gooen: On OpenAl’s messaging:

Some arguments that OpenAl is making, simultaneously:

OpenAl will likely reach and own transformative Al (useful for attracting talent to work there).

OpenAl cares a lot about safety (good for public PR and government regulations).

OpenAl isn’t making anything dangerous and is unlikely to do so in the future (good for public PR and government regulations).

OpenAl doesn’t need to spend many resources on safety, and implementing safe Al won’t put it at any competitive disadvantage (important for investors who own most of the company).

Transformative Al will be incredibly valuable for all of humanity in the long term (for public PR and developers).

People at OpenAl have thought long and hard about what will happen, and it will be fine.

We can’t predict concretely what transformative Al will look like or what will happen after (Note: Any specific scenario they propose would upset a lot of people. Value hand-waving upsets fewer people).

OpenAl can be held accountable to the public because it has a capable board of advisors overseeing Sam Altman (he said this explicitly in an interview).

The previous board scuffle was a one-time random event that was a very minor deal.

OpenAl has a nonprofit structure that provides an unusual focus on public welfare.

The nonprofit structure of OpenAl won’t inconvenience its business prospects or shareholders in any way.

The name “OpenAl,” which clearly comes from the early days when the mission was actually to make open-source Al, is an equally good name for where the company is now. (I don’t actually care about this, but find it telling that the company doubles down on arguing the name still is applicable).

So they need to simultaneously say:

“We’re making something that will dominate the global economy and outperform humans at all capabilities, including military capabilities, but is not a threat.”

“Our experimental work is highly safe, but in a way that won’t actually cost us anything.” “We’re sure that the long-term future of transformative change will be beneficial, even though none of us can know or outline specific details of what that might actually look like.”

“We have a great board of advisors that provide accountability. Sure, a few months ago, the board tried to fire Sam, and Sam was able to overpower them within two weeks, but next time will be different.”

“We have all of the benefits of being a nonprofit, but we don’t have any of the costs of being a nonprofit.”

Meta’s messaging is clearer: “Al development won’t get us to transformative Al, we don’t think that Al safety will make a difference, we’re just going to optimize for profitability.”

Anthropic’s messaging is a bit clearer. “We think that Al development is a huge deal and correspondingly scary, and we’re taking a costlier approach accordingly, though not too costly such that we’d be irrelevant.” This still requires a strange and narrow worldview to make sense, but it’s still more coherent.

But OpenAl’s messaging has turned into a particularly tangled mess of conflicting promises. It’s the kind of political strategy that can work for a while, especially if you can have most of your conversations in private, but is really hard to pull off when you’re highly public and facing multiple strong competitive pressures.

If I were a journalist interviewing Sam Altman, I’d try to spend as much of it as possible just pinning him down on these countervailing promises they’re making. Some types of questions I’d like him to answer would include:

“Please lay out a specific, year-by-year, story of one specific scenario you can imagine in the next 20 years.”

“You say that you care deeply about long-term Al safety. What percentage of your workforce is solely dedicated to long-term Al safety?”

“You say that you think that globally safe AGI deployments require international coordination to go well. That coordination is happening slowly. Do your plans work conditional on international coordination failing? Explain what your plans would be.”

“What do the current prediction markets and top academics say will happen as a result of OpenAl’s work? Which clusters of these agree with your expectations?”

“Can you lay out any story at all for why we should now expect the board to do a decent job overseeing you?”

What Sam likes to do in interviews, like many public figures, is to shift specific questions into vague generalities and value statements. A great journalist would fight this, force him to say nothing but specifics, and then just have the interview end.

I think that reasonable readers should, and are, quickly learning to just stop listening to this messaging. Most organizational messaging is often dishonest but at least not self-rejecting. Sam’s been unusually good at seeming genuine, but at this point, the set of incoherent promises is too baffling to take seriously.

Instead, the thing to do is just ignore the noise. Look at the actual actions taken alone. And those actions seem pretty straightforward to me. OpenAl is taking the actions you’d expect from any conventional high-growth tech startup. From its actions, it comes across a lot like: “We think Al is a high-growth area that’s not actually that scary. It’s transformative in a way similar to Google and not the Industrial Revolution. We need to solely focus on developing a large moat (i.e. monopoly) in a competitive ecosystem, like other startups do.”

OpenAl really seems almost exactly like a traditional high-growth tech startup now, to me. The main unusual things about it are the facts that (A) it’s in an area that some people (not the OpenAl management) think is very usually high-risk, (B) its messaging is unusually lofty and conflicting, even for a Silicon Valley startup, and (C) it started out under an unusual nonprofit setup, which now barely seems relevant.

I think that reasonable readers should, and are, quickly learning to just stop listening to this messaging. Most organizational messaging is often dishonest but at least not self-rejecting. Sam’s been unusually good at seeming genuine, but at this point, the set of incoherent promises seems too baffling to take literally.

Instead, I think the thing to do is just ignore the noise. Look at the actual actions taken alone. And those actions seem pretty straightforward to me. OpenAI is taking the actions you’d expect from any conventional high-growth tech startup. From its actions, it comes across a lot like:

“We think AI is a high-growth area that’s not actually that scary. It’s transformative in a way similar to Google and not the Industrial Revolution. We need to solely focus on developing a large moat (i.e. monopoly) in a competitive ecosystem, like other startups do.”

OpenAI really seems almost exactly like a traditional high-growth tech startup now, to me. The main unusual things about it are the facts that:

Its in an area that some people (not the OpenAI management) think is unusually high-risk,

Its messaging is unusually lofty and conflicting, even for a Silicon Valley startup, and

It started out under an unusual nonprofit setup, which now barely seems relevant.

Ben Henry: Great post. I believe he also has said words to the effect of:

Working on algorithmic improvements is good to prevent hardware overhang.

We need to invest more in hardware.

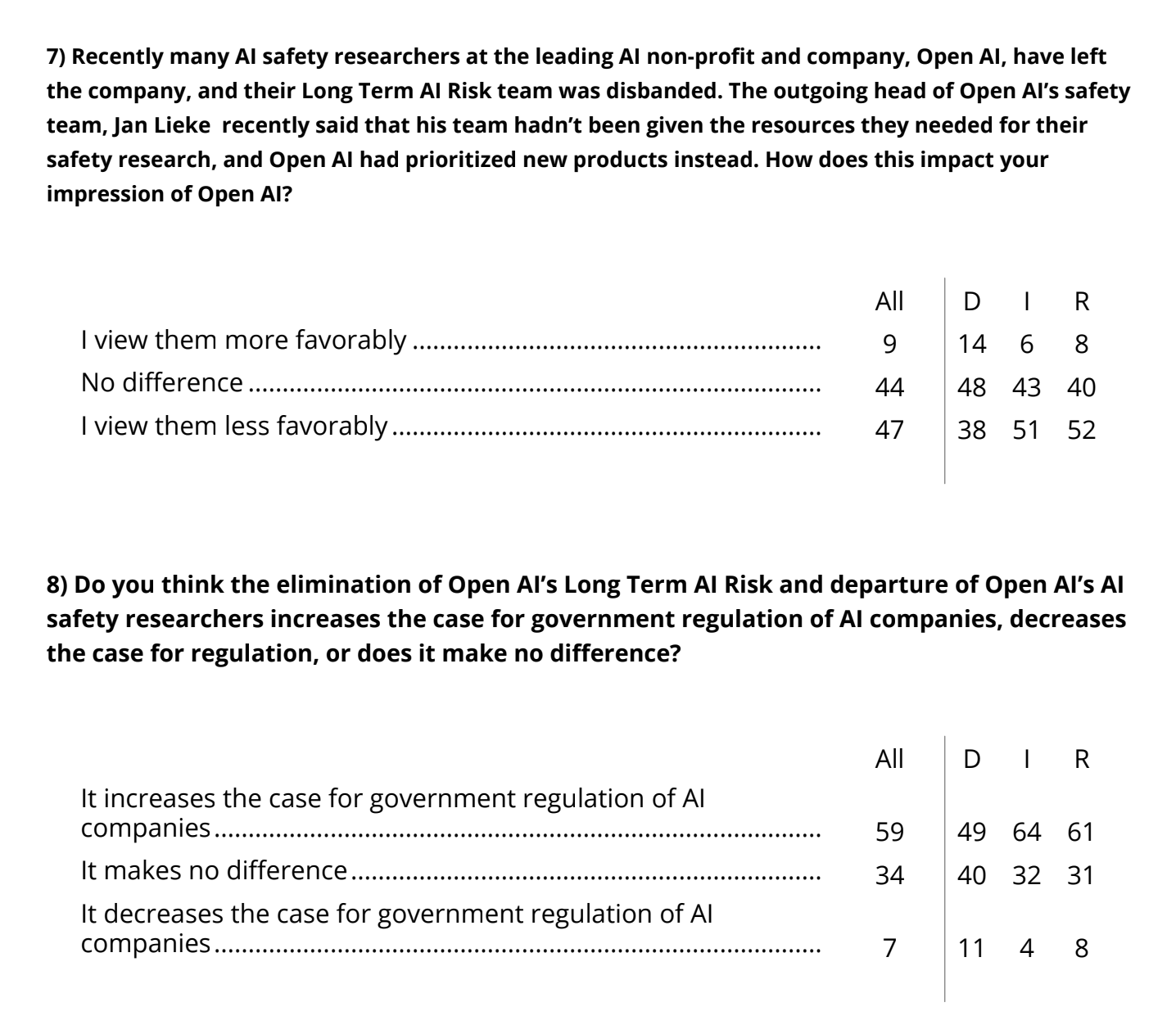

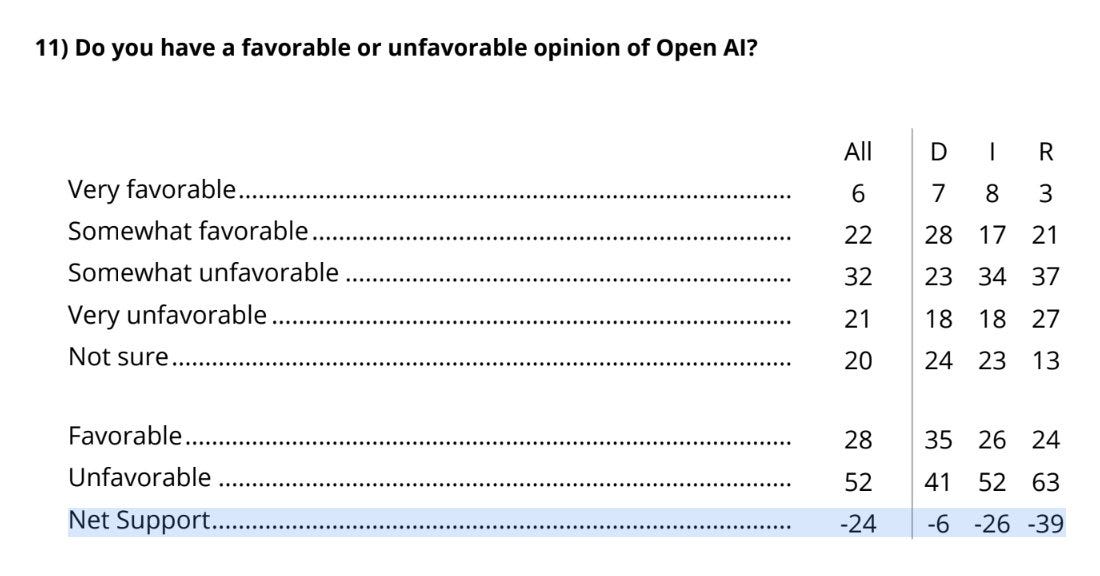

A survey was done. You can judge for yourself whether or not this presentation was fair.

Thus, this question overestimates the impact, as it comes right after telling people such facts about OpenAI:

As usual, none of this means the public actually cares. ‘Increases the case for’ does not mean increases it enough to notice.

Individuals paying attention are often… less kind.

Here are some highlights.

Brian Merchant: “Open” AI is now a company that:

-keeps all of its training data and key operations secret

-forced employees to sign powerful NDAs or forfeit equity

-won’t say whether it trained its video generator on YouTube

-lies to movie stars then lies about the lies

“Open.” What a farce.

[links to two past articles of his discussing OpenAI unkindly.]

Ravi Parikh: If a company is caught doing multiple stupid & egregious things for very little gain

It probably means the underlying culture that produced these decisions is broken.

And there are dozens of other things you haven’t found out about yet.

Jonathan Mannhart (reacting primarily to the Scarlett Johansson incident, but centrally to the pattern of behavior): I’m calling it & ramping up my level of directness and anger (again):

OpenAI, as an organisation (and Sam Altman in particular) are often just lying. Obviously and consistently so.

This is incredible, because it’s absurdly stupid. And often clearly highly unethical.

Joe Weisenthal: I don’t have any real opinions on AI, AGI, OpenAI, etc. Gonna leave that to the experts.

But just from the outside, Sam Altman doesn’t ~seem~ like a guy who’s, you know, doing the new Manhattan Project. At least from the tweets, podcasts etc. Seems like a guy running a tech co.

Andrew Rettek: Everyone is looking at this in the context of AI safety, but it would be a huge story if any $80bn+ company was behaving this way.

Danny Page: This thread is important and drives home just how much the leadership at OpenAI loves to lie to employees and to the public at large when challenged.

Seth Burn: Just absolutely showing out this week. OpenAI is like one of those videogame bosses who looks human at first, but then is revealed to be a horrific monster after taking enough damage.

0.005 Seconds: Another notch in the “Altman lies likes he breathes” column.

Ed Zitron: This is absolutely merciless, beautifully dedicated reporting, OpenAI is a disgrace and Sam Altman is a complete liar.

Keller Scholl: If you thought OpenAI looked bad last time, it was just the first stage. They made all the denials you expect from a company that is not consistently candid: Piper just released the documents showing that they lied.

Paul Crowley: An argument I’ve heard in defence of Sam Altman: given how evil these contracts are, discovery and a storm of condemnation was practically inevitable. Since he is a smart and strategic guy, he would never have set himself up for this disaster on purpose, so he can’t have known.

Ronny Fernandez: What absolute moral cowards, pretending they got confused and didn’t know what they were doing. This is totally failing to take any responsibility. Don’t apologize for the “ambiguity”, apologize for trying to silence people by holding their compensation hostage.

I have, globally, severely downweighted arguments of the form ‘X would never do Y, X is smart and doing Y would have been stupid.’ Fool me [quite a lot of times], and such.

Eliezer Yudkowsky: Departing MIRI employees are forced to sign a disparagement agreement, which allows us to require them to say unflattering things about us up to three times per year. If they don’t, they lose their OpenAI equity.

Rohit: Thank you for doing this.

Rohit quotes himself from several days prior: OpenAI should just add a disparagement clause to the leaver documentation. You can’t get your money unless you say something bad about them.

There is of course an actually better way, if OpenAI wants to pursue that. Unless things are actually much worse than they appear, all of this can still be turned around.

OpenAI says it should be held to a higher standard, given what it sets out to build. Instead, it fails to meet the standards one would set for a typical Silicon Valley business. Should you consider working there anyway, to be near the action? So you can influence their culture?

Let us first consider the AI safety case, and assume you can get a job doing safety work. Does Daniel Kokotajlo make an argument for entering the belly of the beast?

Michael Trazzi:

> be daniel kokotajlo

> discover that AGI is imminent

> post short timeline scenarios

> entire world is shocked

> go to OpenAI to check timelines

> find out you were correct

> job done, leave OpenAI

> give up 85% of net worth to be able to criticize OpenAI

> you’re actually the first one to refuse signing the exit contract

> inadvertently shatter sam altman’s mandate of heaven

> timelines actually become slightly longer as a consequence

> first time in your life you need to update your timelines, and the reason they changed is because the world sees you as a hero

Stefan Schubert: Notable that one of the (necessary) steps there was “join OpenAI”; a move some of those who now praise him would criticise.

There are more relevant factors, but from an outside view perspective there’s some logic to the notion that you can influence more from the centre of things.

Joern Stoehler: Yep. From 1.5y to 1w ago, I didn’t buy arguments of the form that having people who care deeply about safety at OpenAI would help hold OpenAI accountable. I didn’t expect that joining-then-leaving would bring up legible evidence for how OpenAI management is failing its goal.

Even better, Daniel then get to keep his equity, whether or not OpenAI lets him sell it. My presumption is they will let him given the circumstances, I’ve created a market.

Most people who attempt this lack Daniel’s moral courage. The whole reason Daniel made a difference is that Daniel was the first person who refused to sign, and was willing to speak about it.

Do not assume you will be that courageous when the time comes, under both bribes and also threats, explicit and implicit, potentially both legal and illegal.

Similarly, your baseline assumption should be that you will be heavily impacted by the people with whom you work, and the culture of the workplace, and the money being dangled in front of you. You will feel the rebukes every time you disrupt the vibe, the smiles when you play along. Assume that when you dance with the devil, the devil don’t change. The devil changes you.

You will say ‘I have to play along, or they will shut me out of decisions, and I won’t have the impact I want.’ Then you never stop playing along.

The work you do will be used to advance OpenAI’s capabilities, even if it is nominally safety. It will be used for safety washing, if that is a plausible thing, and your presence for reputation management and recruitment.

Could you be the exception? You could. But you probably won’t be.

In general, ‘if I do not do the bad thing then someone else will do the bad thing and it will go worse’ is a poor principle.

Do not lend your strength to that which you wish to be free from.

What about ‘building career capital’? What about purely in your own self-interest? What if you think all these safety concerns are massively overblown?

Even there, I would caution against working at OpenAI.

That giant equity package? An albatross around your neck, used to threaten you. Even if you fully play ball, who knows when you will be allowed to cash it in. If you know things, they have every reason to not let you, no matter if you so far have played ball.

The working conditions? The nature of upper management? The culture you are stepping into? The signs are not good, on any level. You will hold none of the cards.

If you already work there, consider whether you want to keep doing that.

Also consider what you might do to gather better information, about how bad the situation has gotten, and whether it is a place you want to keep working, and what information the public might need to know. Consider demanding change in how things are run, including in the ways that matter personally to you. Also ask how the place is changing you, and whether you want to be the person you will become.

As always, everyone should think for themselves, learn what they can, start from what they actually believe about the world and make their own decisions on what is best. As an insider or potential insider, you know things outsiders do not know. Your situation is unique. You hopefully know more about who you would be working with and under what conditions, and on what projects, and so on.

What I do know is, if you can get a job at OpenAI, you can get a lot of other jobs too.

As you can see throughout, Kelsey Piper is bringing the fire.

There is no doubt more fire left to bring.

Kelsey Piper: I’m looking into business practices at OpenAI and if you are an employee or former employee or have a tip about OpenAI or its leadership team, you can reach me at [email protected] or on Signal at 303-261-2769.

If you have information you want to share, on any level of confidentiality, you can also reach out to me. This includes those who want to explain to me why the situation is far better than it appears. If that is true I want to know about it.

There is also the matter of legal representation for employees and former employees.

What OpenAI did to its employees is, at minimum, legally questionable. Anyone involved should better know their rights even if they take no action. There are people willing to pay your legal fees, if you are impacted, to allow you to consult a lawyer.

Kelsey Piper: If [you have been coerced into signing agreements you cannot talk about], please talk to me. I’m on Signal at 303-261-2769. There are people who have come to me offering to pay your legal fees.

Here Vilfredo’s Ghost, a lawyer, notes that a valid contract requires consideration and a ‘meeting of the minds,’ and common law contract principles do not permit surprises. Since what OpenAI demanded is not part of a typical ‘general release,’ and the only consideration provided was ‘we won’t confiscate your equity’ or deny you the right to sell it, the contract looks suspiciously like it would be invalid.

Matt Bruenig has a track record of challenging the legality of similar clauses, and has offered his services. He notes that rules against speaking out about working conditions are illegal under federal law, but if they do not connect to ‘working conditions’ then they are legal. Our laws are very strange.

It seems increasingly plausible that it would be in the public interest to ban non-disparagement clauses more generally going forward, or at least set limits on scope and length (although I think nullifying existing contracts is bad and the government should not do that, and shouldn’t have done it for non-competes either.)

This is distinct from non-disclosure in general, which is clearly a tool we need to have. But I do think that, at least outside highly unusual circumstances, ‘non-disclosure agreements should not apply to themselves’ is also worth considering.

Thanks to the leverage OpenAI still holds, we do not know what other information is out there, as of yet not brought to light.

Repeatedly, OpenAI has said it should be held to a higher standard.

OpenAI instead under Sam Altman has consistently failed to live up not only to the standards to which one must hold a company building AGI, but also the standards one would hold an ordinary corporation. Its unique non-profit structure has proven irrelevant in practice, if this is insufficient for the new board to fire Altman.

This goes beyond existential safety. Potential and current employees and business partners should reconsider, if only for their own interests. If you are trusting OpenAI in any way, or its statements, ask whether that makes sense for you and your business.

Going forward, I will be reacting to OpenAI accordingly.

If that’s not right? Prove me wrong, kids. Prove me wrong.