Battle of the AI bands —

But it still needs trial and error to generate high-quality results.

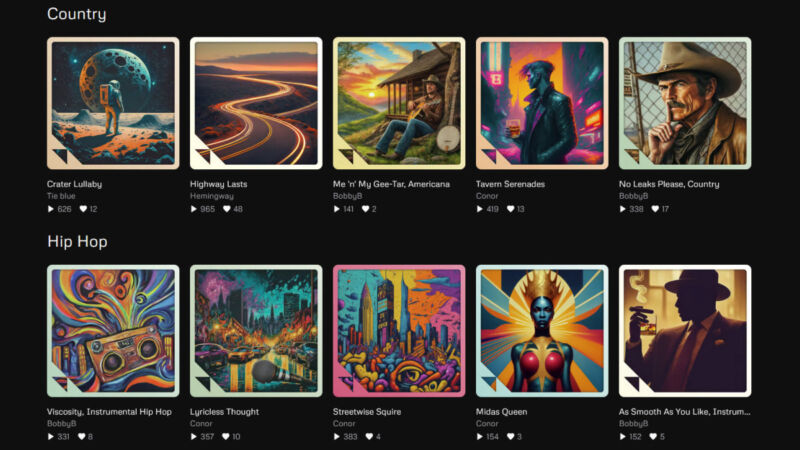

Enlarge / A screenshot of AI-generated songs listed on Udio on April 10, 2024.

Benj Edwards

Between 2002 and 2005, I ran a music website where visitors could submit song titles that I would write and record a silly song around. In the liner notes for my first CD release in 2003, I wrote about a day when computers would potentially put me out of business, churning out music automatically at a pace I could not match. While I don’t actively post music on that site anymore, that day is almost here.

On Wednesday, a group of ex-DeepMind employees launched Udio, a new AI music synthesis service that can create novel high-fidelity musical audio from written prompts, including user-provided lyrics. It’s similar to Suno, which we covered on Monday. With some key human input, Udio can create facsimiles of human-produced music in genres like country, barbershop quartet, German pop, classical, hard rock, hip hop, show tunes, and more. It’s currently free to use during a beta period.

Udio is also freaking out some musicians on Reddit. As we mentioned in our Suno piece, Udio is exactly the kind of AI-powered music generation service that over 200 musical artists were afraid of when they signed an open protest letter last week.

But as impressive as the Udio songs first seem from a technical AI-generation standpoint (not necessarily judging by musical merit), its generation capability isn’t perfect. We experimented with its creation tool and the results felt less impressive than those created by Suno. The high-quality musical samples showcased on Udio’s site likely resulted from a lot of creative human input (such as human-written lyrics) and cherry-picking the best compositional parts of songs out of many generations. In fact, Udio lays out a five-step workflow to build a 1.5-minute-long song in a FAQ.

For example, we created an Ars Technica “Moonshark” song on Udio using the same prompt as one we used previously with Suno. In its raw form, the results sound half-baked and almost nightmarish (here is the Suno version for comparison). It’s also a lot shorter by default at 32 seconds compared to Suno’s 1-minute and 32-second output. But Udio allows songs to be extended, or you can try generating a poor result again with different prompts for different results.

After registering a Udio account, anyone can create a track by entering a text prompt that can include lyrics, a story direction, and musical genre tags. Udio then tackles the task in two stages. First, it utilizes a large language model (LLM) similar to ChatGPT to generate lyrics (if necessary) based on the provided prompt. Next, it synthesizes music using a method that Udio does not disclose, but it’s likely a diffusion model, similar to Stability AI’s Stable Audio.

From the given prompt, Udio’s AI model generates two distinct song snippets for you to choose from. You can then publish the song for the Udio community, download the audio or video file to share on other platforms, or directly share it on social media. Other Udio users can also remix or build on existing songs. Udio’s terms of service say that the company claims no rights over the musical generations and that they can be used for commercial purposes.

Although the Udio team has not revealed the specific details of its model or training data (which is likely filled with copyrighted material), it told Tom’s Guide that the system has built-in measures to identify and block tracks that too closely resemble the work of specific artists, ensuring that the generated music remains original.

And that brings us back to humans, some of whom are not taking the onset of AI-generated music very well. “I gotta be honest, this is depressing as hell,” wrote one Reddit commenter in a thread about Udio. “I’m still broadly optimistic that music will be fine in the long run somehow. But like, why do this? Why automate art?”

We’ll hazard an answer by saying that replicating art is a key target for AI research because the results can be inaccurate and imprecise and still seem notable or gee-whiz amazing, which is a key characteristic of generative AI. It’s flashy and impressive-looking while allowing for a general lack of quantitative rigor. We’ve already seen AI come for still images, video, and text with varied results regarding representative accuracy. Fully composed musical recordings seem to be next on the list of AI hills to (approximately) conquer, and the competition is heating up.