Previous Fertility Roundups: #1, #2.

The pace seems to be doing this about twice a year. The actual situation changes slowly, so presumably the pace of interesting new things should slow down over time from here.

This time around, a visualization. Where will the next 1,000 babies be born?

Scott Lincicome notes American population now expected to peak in 2080 at 369 million.

South Korea now down to 0.7 births per woman. The story of South Korea is told as a resounding success, of a country that made itself rich and prosperous. But what does it profit us, if we become nominally rich and prosperous, but with conditions so hostile that we cannot or will not bring children into them? If the rule you followed led you here, of what use was the rule? Why should others follow it?

More Births reminds us that we have indeed seen countries fall below replacement level and come roaring back, most famously in the Baby Boom. Cultural trends can go any number of ways.

Basil: The fertility rate drops from 2015 -> 2023 are insane in just EIGHT YEARS:

France: 1.96 -> 1.68

Sweden: 1.85 -> 1.42

America: 1.84 -> 1.64

UK: 1.78 -> 1.45

Russia: 1.78 -> 1.41

China: 1.75 -> 1.05 (wtf)

Germany: 1.50 -> 1.42

South Korea: 1.24 -> .73 (jesus christ)

Netherlands: 1.55 -> 1.45

Canada: 1.60 -> 1.25

Japan: 1.45 -> 1.21

Poland: 1.44 -> 1.28

Taiwan: 1.18 -> 0.86

Those are LFR numbers, so the actual changes are presumably bigger.

Singapore falls to historic low of 0.97. New figures have South Korea at 0.72.

I continue to say that if the numbers can decline this fast, they can also bounce back. Indeed do many things come to pass, and we can expect transformational technological change. Things have looked bleak or inevitable before. Don’t lose hope.

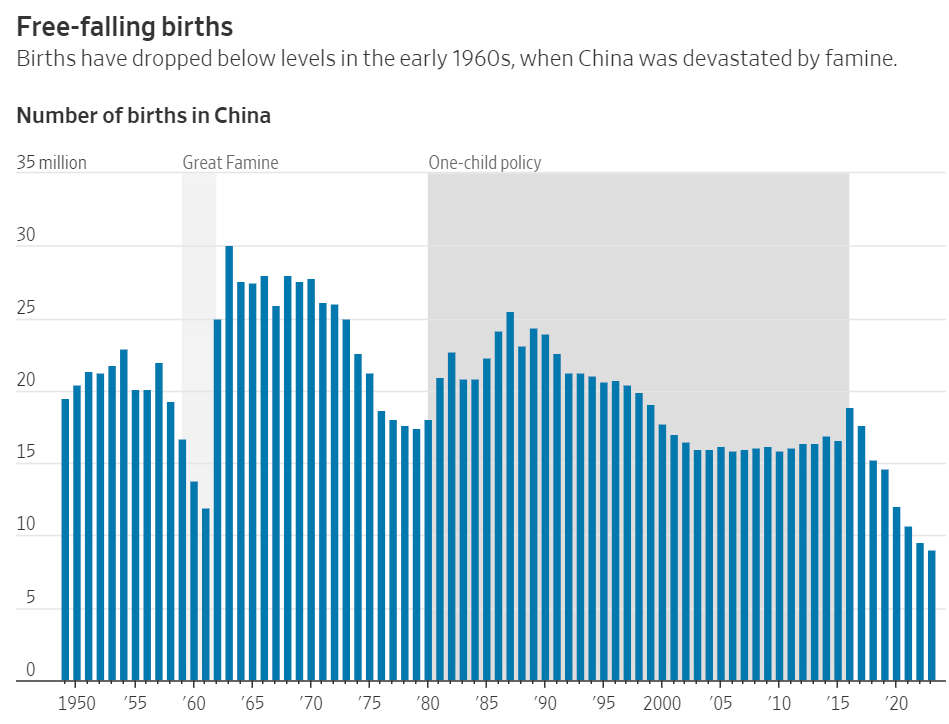

After that, China’s numbers came in for 2023 and they are even worse. The population already shrunk by 2 million in 2023, a trend that will rapidly accelerate by default.

That WSJ article ends with a Harvard professor saying China should not pursue ‘higher’ birthrates, allowing itself to quickly cease to exist, in order to instead address nominal measures of well being.

Martin Whyte, a sociology professor emeritus at Harvard University, said in an essay in China-US Focus, run by the independent China-United States Exchange Foundation, last year that instead of pursuing higher birthrates, China should focus on improving the welfare of its people, such as expanding education opportunities for rural youths and reducing gender discrimination.

What is the point of ‘opportunity’ and non-discrimination, if there is no future? What use is an education in a rapidly aging and thus economically crashing country facing a population collapse?

Emmett Shear points out that people see gradients of relative reward, rather than looking at absolute rewards. This is a key reason that as societies get richer, people have fewer kids rather than more kids. If you want to fix this, you need to differentially give parents, and only parents, money, and also other resources including respect and status.

Many who advocate for pro-fertility policies end up focusing on money because that is an easier knob to turn, and an easier knob to measure in terms of impact, and everyone keeps not trying it. But yes, the true low-hanging fruit is largely in culture.

The boredom theory of fertility, that people have lots of alternative ways to spend their time that do not involve or lead to kids or relationships, or any meaningful interactions with other humans, seems underrated.

Birth Gauge: As the fertility decline was the most pronounced among teenagers and young adults in all of these cases, the widespread availability of affordable smartphones for everyone that started in the mid 2010s is a powerful explanation of the overall trend.

Being connected to the whole virtual world is obviously more interesting than casual unprotected sex, hence the strong decline of teenage pregnancies. The young in middle income countries are also more exposed to developed country living standards.

…

So my feeling is that we are also seeing an increasing ideological divide among young people in developed countries: One group that increasingly consciously decides for having kids and another increasingly consciously decides against having kids.

Misha Gurevich: I wonder if a lot of people have sex/kids out of boredom so alleviation of boredom drives down birth rates. Although probably the actual effect is more indirect. You would rather have sex than swipe on your phone but you would rather swipe on your phone than aimlessly hang around the mall or bar or wherever

BPRS: I remember seeing a study out of India showing drops in fertility correlate more closely in time with arrival of television than any other factor. It was explained as influence of cosmopolitan norms of smaller families, etc, but it could just as well be simple boredom reduction.

Misha Gurevich: In other countries before TV it seems to drop with introduction of widespread education, maybe literacy also has this problem if to a lesser extent

Some more speculation.

Mike Solana: what if there were an epigenetic fertility kill switch activated in dense populations? Constant internet exposure simulates feelings of ultra high density. Ergo, the iPhone did it? Or maybe just the heat the battery throws off in our pocket, but either way I’m blaming jobs.

Ryan Peterson: iPhone did it because of dating apps. People have too many options.

I do not think you can put that much of this on dating apps, there are too many additional impacted steps that this would not impact.

Or one can go with the obvious hypothesis.

Jennifer Leigh: The birth rate is declining because motherhood *costsmoney, jobs *paymoney, and the two are largely incompatible. I’m tired of everyone pretending they don’t understand this.

People like to pretend that the problem is more complex than this but it just isn’t. Maybe the solution is or will be. But the problem absolutely isn’t. It’s simple economics.

The more money a woman can make the higher her opportunity cost is for having kids. Women in wealthier countries may be better able to afford child related expenses but they also have higher motherhood cost.

Another often missed point when talking about the past with regards to birth rates is that children used to be an economic *benefit*. They worked. The 1950s model of nuclear family with kids at school, dad at work, and mom at home was not the norm for most of human history. For most of history the norm was that the whole family “worked”, including children.

I would include costs beyond money. Otherwise? Yes.

Children cost vast amounts of time and money, and we bar any attempts to use them to recoup those costs. If you want to make the necessary money, you mostly need to spend time, and increasingly modern work has increasing marginal returns to time. Meanwhile, we have made raising children far less rewarding and pleasant, on top of its economic burden.

Reduce the time and other lifestyle costs of raising children, reduce the monetary costs, provide other benefits, pay parents money. Ideally in that order. This isn’t hard.

Robin Hanson: “U.S. government would have to spend approximately half of its expected lifetime tax receipts if it wanted to fully offset families’ costs of having a child.” So, its feasible then.

Eliezer Yudkowsky: On the pronatalist side, deregulate childcare first and then talk about pumping demand? Otherwise you’ll just build another Infinite Cost Engine like with housing, healthcare, and college. Never let government try to pay for anything where the government has also built a supply bottleneck.

This is not a critique of Robin Hanson. You can always trust Robin to be consistent from his own perspective and he’s usually pretty consistent from my own perspective too.

I would indeed vastly prefer to deregulate childcare, but also we have not regulated any of this via hard caps that would eat any subsidies we gave to parents. I do not think this is an infinite cost engine as such. So I do think the subsidy plan would work. And I agree with Robin that, while the costs look extreme, the return on investment to even the most brute force interventions is clearly positive. There are still vastly better ways.

More Births gets into a debate with Ross Douthat about cultural causes of declining fertility, disputing Douthat’s claim that Ehrlich’s ideas and related motivations are not a major factor. There is indeed a major actively anti-natal movement in play.

The anti-planner claims that South Korea has such a low birth rate in large part because of its high rises. Without the room for more kids, people don’t have more kids.

I see two potential arguments one can make here. One is that square footage of your apartment is too expensive, because high rises are more expensive than alternative housing, which is the point made here. In that case it is purely about housing prices, and I expect the additional high rise construction costs to both not ultimately much matter and to be dwarfed by supply and demand considerations. Besides, if they are so much more expensive, what is stopping the midsize buildings from being built, exactly? This would also be a self-correcting problem as the population declines.

The other case is that it is about outdoor space and distance to the outdoors. If you concentrate that many families in one place, they perhaps have nowhere reasonable to go outside, although the high rises could also allow quite a lot of green space, and elevators work pretty well.

I do believe in the housing theory of everything and that expensive housing is a large part of the problem here, but it seems weird to blame it on the high rises, rather than on the country packing so many people into relatively little space. If anything, as the post notes, Seoul and the other very expansive urban areas are less dense than American cities like Philadelphia, but the solution to that is not to not build high rises, it is to also build more other housing.

Lyman Stone offers another analysis, also centering housing details but also other problems. South Koreans have subsidized housing, yes, but what they get is not good for family life. Formal contracts made it impossible to capture your children’s wages as was previously common, and the welfare state is weak, so everyone is obsessed with saving as much money as possible.

On the issue of gender inequality, Lyman points to the gap in attitudes, that men think the women are too feminist and the women think the men are too sexist, so they can’t reach harmony. Then there’s the k-pop music industry (!), which is heavily state-supported, a pervasive cultural phenomenon, and contractually single, childless and youth focused, driving cultural norms.

Phoebe Arslangic-Little asks why free taxis, free IVF and subsidized housing, which she calls ‘showering couples with cash’ hasn’t worked. Right off the bat I would say, yes that all helps, but define ‘showering.’ The subsidies offered a small fraction of total economic costs, and are dwarfed by the changes and issues raised by Lyman Stone.

Phoebe instead focuses on sexist attitudes pressuring women. And yeah, it sounds bad.

Phoebe Arslangic-Little: Sexist attitudes put tremendous pressure on South Korean women.

In 2019 the government warned pregnant women not to look disheveled while cooking their husband’s meals…

And 53% of South Koreans think women have less right to a job than men when jobs are scarce.

Workplace maternity discrimination is also rife, forcing women to choose between parenthood and a career.

As a result, South Korea has the biggest gender pay gap in the OECD.

Change is happening, but there is a growing backlash, with young South Korean men spearheading a vigorous anti-feminist movement.

…

Adding a post to reflect an extremely good point made by @lymanstoneky (& others): “Where Korea is unique is in the yawning gap in gender attitudes between reproductive age men and women.” It’s this values gap especially that contributes to SK’s problems.

Traditional sexist attitudes and sexism were more severe than this pretty much everywhere, and made life worse in many ways for women and especially mothers. They were however part of a cultural package selected and designed in large part for high fertility.

If you get rid of the sexism, life improves, but you also remove the cultural package that was enhancing fertility. Without the help and together with the shifting economics and other realities of raising a family, fertility seems to reliably drop below replacement, so you need to replace the old incentives with new ones somehow.

You can, however, do so much worse.

If you get rid of the fertility-load-bearing parts of the old culture, but you keep the sexism, as appears to be what happened in South Korea, then you get the worst of both worlds. Life sucks a lot more whether you have kids or not, and you make having children look like a stupendously bad deal, so people don’t do it.

It is hard to look at a government that warns pregnant women ‘not to look disheveled while cooking their husband’s meals’ and see one that cares about fertility. Or a government that heavily subsidizes its pop music industry while forcing its stars to remain single and childless, as I will discuss below.

So yes, that is how you get a situation where you can correctly respond to ‘how can we raise fertility’ with ‘you need more gender equality and less sexism.’ We know from other places that fixing that will not be sufficient, but at this point it seems necessary.

More Births highlights the k-pop angle, where its stars are forced to stay single and childless, and speculates it is a big deal. It is certainly a factor unique to South Korea.

More Births: Although it would be difficult to prove, it seems likely that the KPOP industry’s bizarre demand that its stars remain single is reinforcing a sexless and childless culture. This may be hurting global fertility rates given KPOP’s massive global reach.

If K-Pop made an effort to be supportive of its stars having partners and families, that could boost fertility in 🇰🇷 and worldwide!

Not only that – if K-Pop became pro-family, it would likely boost relations with the North, which is deeply distrustful of the South’s culture.

Stone points to the vast political divide between men and women in South Korea as another thing that is likely lowering birthrates. I concur. I wrote last month how these days, inter-political marriage is less common than interracial marriage!

I have no idea the magnitude of the impact of k-pop, but it sure isn’t helping. A government that was serious about saving the country would pivot to a pro-family cultural agenda.

South Korea also has to fix the economics. Phoebe only mentions IVF:

Phoebe Arslangic-Little: South Korea’s policies aren’t working at least in part because free IVF does nothing to end the sharp trade-off between career and motherhood that women face, or to alleviate the pressure of traditional gender attitudes.

It is odd to focus this much on IVF. Even at $0, this is still a rather annoying procedure. Even in South Korea it is only responsible for 7.2% of births versus 2.1% in the United States. That’s an additional 5.1% of births, presumably as a result of making it free, not all of which are additional counterfactual births, although I think most of them are. Also, ‘free’ is a misnomer here, they subsidize but it is far from the full cost.

They should pay for all of it within reason (obviously not infinite cycles for incentive reasons), as a first step or down payment.

Free IVF is great because you are mostly subsidizing marginal births, and doing so exactly at the pain point and where there is a liquidity crunch. Notice how nicely targeted the subsidy looks. The subsidy is really tiny, and I can see how this both unlocks a real liquidity or affordability bottleneck, and also changes the emotional valiance of the decision far out of proportion to the amount.

So this is likely a key part of the low hanging fruit of subsidizing more births, the most efficient path we have available. We already essentially think health care should be a human right and mostly covered by insurance everyone has, so in a sense the marginal cost here is very close to zero.

Here is another perspective. A new paper argues that a major cause of South Korean low fertility is status competition, in particular pressure to spend on education.

East Asians, especially South Koreans, appear to be preoccupied with their offspring’s education—most children spend time in expensive private institutes and in cram schools in the evenings and on weekends. At the same time, South Korea currently has the lowest total fertility rate in the world. Motivated by novel empirical evidence on spillovers in private education spending, we propose a theory with status externalities and endogenous fertility that connects these two facts.

Using a quantitative heterogeneous-agent model calibrated to Korea, we find that fertility would be 28% higher in the absence of the status externality and that childlessness in the poorest quintile would fall from five to less than one percent. We then explore the effects of various government policies. A pro-natal transfer or an education tax can increase fertility and reduce education spending, with heterogeneous effects across the income distribution.

The policy mix that maximizes the current generation’s welfare consists of an education tax of 22% and moderate pro-natal transfers.

This would raise average fertility by about 11% and decrease education spending by 39%. Although this policy increases the welfare of the current generation, it may not do the same for future generations as it lowers their human capital.

Academics cannot fathom the idea that education spending might not enhance human capital at the margin. In a hyper-competitive system where every child’s lives are swallowed by the competition, often along with those of the parents and also their bank accounts, and without the slack to succeed via actual curiosity and learning? It seems likely that the education spending is actively wasteful.

If my calculations are correct, then a tax on education spending, which is then remitted to parents generally, is clearly welfare-improving across the board.

The current situation is clearly unsustainable on its face:

Another notable feature of Korean society is that children’s education is very highly valued by parents. This preoccupation with education is sometimes called “education fever,” echoing the title of a popular book by Michael Seth (2002). Many teenagers attend math and English classes in private education institutes called hagwons, often as late as midnight. Others, meanwhile, spend numerous hours each week with a private tutor.

Participation rates in after-school programs are around 75%. These private education investments are so expensive that, on average, an individual family spends as much as 9.2% of their income per child on education (even though most children attend public schools).

In this paper, we propose a new mechanism that connects high education spending with low birth rates. The novel ingredient is a status externality in which parents value the education of their children relative to the education of other children

Yes. Because that is what education is primarily about at such margins. It is a zero-sum status competition, a signaling game, a Red Queen’s race.

Using regional variation in the change of late-night curfews on hagwons as instruments, we find that lower spending on private education among relatively rich families lowered private education expenditures of socioeconomically disadvantaged (i.e., low-income or low-education) families.

This is not obviously the correct way to react if you seek relative status. If high-income families are investing less in their children’s education, then that likely increases rather than decreases returns to effort by low-income families, as they have a better chance of getting ahead.

So this seems a lot more like cultural pressures and norms and patterns? You see what others are doing, you feel you must do it also.

Whereas the correct way to play is actually the opposite. In America a few decades ago, when others are putting in relatively low effort considering, you could reliably get to an elite college via the tiger mom all-in high-investment strategy. That is plausibly a very good return.

Whereas in South Korea now, if you run that race, everyone is running it with you, all you are doing is staying put as everyone drowns. The only way to win is not to play. As the population shrinks and there are too few workers for too many jobs, your well-rounded kids who stayed home learning to code will thrive, and you could afford more of them that way.

Note that the intervention mechanism still works, and perhaps works better, if everyone is trying to make educational investments relative to those around them, rather than trying to get relative status via results.

The paper attempts to estimate the fertility effects of transfers. They compare their results to Kim (2020), which found that cash transfers raised the fertility rate in South Korea by 3%, with payments of very roughly 680 USD for the first child, 926 for the second and 2,350 for the third. Also note:

Hong et al. (2016) estimate the causal effect of these transfers in Korea using regional and time variation, finding that a one-time cash bonus of 1,000 USD increases the crude birth rate by 4.4%.

So that’s a very easy one to estimate from, you pay a little under $23k per birth. That is super affordable. Still, I question the methodologies here. The new paper seems not to have great justification for its calculations. I find them plausible, but a lot of numbers could be plausible.

Every time I read about South Korea the situation seems worse. The linked post has women working 9-6, saying they have no time for anything else, often studying and getting an IV drip on weekends to be able to keep working and acting like that is normal, talk of women forced to leave their jobs or passed over for promotions due to having a child.

South Korea teaches women they are supposed to be the equals of men. Then it exerts, on everyone, pressures that will crush you if you take on something like a family, and also teaches everyone that men are useless at home, so women are told they should choose career over family then told they must choose. So they do.

Also there is talk of expensive supplemental classes mentioned above as essentially culturally mandatory starting at age four, with 94% (!!!) saying it was a financial burden and only 2% not paying private tuition, with the resulting pressure consuming everyone through their 20s.

Only now, aged 32, does Minji feel free, and able to enjoy herself. She loves to travel and is learning to dive.

But her biggest consideration is that she does not want to put a child through the same competitive misery she experienced.

If it is truly that bad, then there are essentially three choices: Ban, tax or pay for it. Given it is a dystopian status competition hell, pay for it seems terrible, but if we have 98% participation now and 94% financial hardship, then this could be a way to justify a huge de facto transfer to parents.

If New York City paid $20,000 per child per year to parents, everyone would be screaming about how awful that was and how parents would have kids to collect the check. Pay that much and more per child for public schools and no one much minds. That’s the reason to do in-kind payments, it makes them politically viable by guarding against profiteering.

Something is going to have to give. It is time for a lot More Dakka.

It looks like rather large payments for children are indeed about to be tried in South Korea. Not on a country level, which would be ideal, but rather on a corporate level. At $75,000 per birth, this is serious money, enough to actually change people’s decisions, as opposed to a ‘baby payment’ of $2,250 that is nice but not going to move the needle so much.

The potential selection problems are obvious. Once you announce the policy, people will want to work for you if they already planned on having children. That makes it impossible to know how many additional births this actually induced. My guess is it is still quite a lot.

Also I am betting that you get a ton of very good workers, very loyal to you and to each other, who come together as a team and kick serious butt.

If something like this does not work, the next step I suppose is to accept that South Korea has a culture where women cannot have it all, that there is no slack permitted in life, and that this problem exists in increasingly many places but they have it the worst.

Which implies three potential solutions if you have to intervene economically rather than directly on culture. You can do one or more.

-

Either you can actually pass and enforce labor laws that make families compatible with having good jobs and provide enough incentive to the employer that they can go along with it.

-

Or you can accept that being a mother is going to be a full-time job, you can create paths to doing a new type of less intensive job that is compatible and provide regulatory or monetary subsidies to that.

-

Or you can fully bite the bullet and say that being a mother of sufficiently many children is a noble full time job and compensate it like you mean that. As in, pay them a large fraction of the median salary and do it even if they have a husband that works. You don’t have to like it, but there are no good choices.

What determines the amount that is affordable?

Simone Collins: Is there some amount we could pay people to get them to have kids? Of course. Is there an amount a government would be able to pay (i.e., something that would pass in Congress) that would make a significant difference? The answer is no. Anyone telling you otherwise is either not familiar with the data or is lying to you in an effort to promote some other agenda.

Robin Hanson: There is in fact an amount that would induce kids that govt could afford to pay, via borrowing on the future taxes those kids would pay. Whether Congress might vote for that seems an open question.

Right now, nothing will pass Congress, so obviously nothing that works will pass either. What about in the future? That depends on how much things shift.

Borrowing against the taxes from a future citizen only counts as ‘affordable’ if you borrow against the surplus, and include the financing costs. A child born today can expect to pay quite a lot in taxes over their lifetime. And of course they already are effectively taking on their share of the national debt. I don’t know exactly what the answer should be here. I am confident that the answer is ‘a lot.’

A claim that subsidizing child care does not raise birth rates, and some very strong counterarguments.

Lyman Stone: I like @jburnmurdoch but this entire post is wrong and detached from the scholarly literature. I appreciate the friendly cites to me, but the thesis is totally wrong.

[technical arguments in thread]

Also, it should be noted that consistency in time use data is low: countries ask it in very different ways and there are huge cultural changes in how people conceive of and report childcare time. Now it’s true parenting time has risen, I don’t dispute that!

But actual policy studies using high-quality causal inference are passed over for a mostly-fake correlational study of mediocre data?

Finally, there’s a deeper theoretical issue here.

Yes, culture is hugely important.

The government shapes the culture.

It’s not ambiguous why marriage rates have disproportionately declined for poor people! It’s because governments pay them not to get married!

Young people are disproportionately poorer and so more exposed to the marriage penalties in means-tested programs. This effect accounts for a very large share of the total marriage rate decline.

Because virtually every welfare state on earth punishes marriage, this also works well to explain the highly correlated decline in marriage across countries: they all rolled out similarly anti-marriage welfare states!

[continues hammering various points]

Robin Hanson: “Analysed across all rich countries, birth rates are no higher among those where childcare is fully subsidised than those where parents pay eye-watering fees … culture is far more powerful than policy … Birth rates in liberal, developed countries look exceptionally unlikely to return to replacement level any time soon. If they miraculously do so, it will most likely be due to broad social & cultural shifts, not policy”

But policy, including money, can BUY cultural shifts! This isn’t either or.

Lyman Stone (later in thread): Free childcare subsidizes babies, yes.

But it also is a tax on babies. In particular, it’s a subsidy (free) you only get if you pay a tax (less time with your kid). Because spending time with your kid is the point of having kids, and because the people most willing…

… to have more kids are people who would like to spend more time with kids, offering a subsidy only available to people willing to reduce time with kids is throwing money at the absolute least efficient part of the fertility decision tree.

‘Free’ childcare is a highly inefficient subsidy. It forces parents to deal with an anti-marriage, and anti-income welfare state, it forces the modality of using commercial childcare at scale which many parents reasonably feel terrible using, it greatly raises the costs of childcare for those not getting the subsidies, and you get the benefits slowly over years in a way that is not so fungible. So one can expect this to be a pretty terrible policy, and also to be substituting for other policy and reflective of a culture that does not understand what it is to be a family or actually value children. It would be unsurprising if it was not correlated with higher birth rates in practice.

Flint, Michigan offers new mothers $1,500 for pregnancy and $500 per month for the first twelve months, with no income test. This seems excellent. Alas, there is a limit to how much a local area can do, given that people can move and the costs are paid locally while benefits largely accrue nationally. Offering $7,500 total is likely on the high end of what is practical before people start inefficiently gaming the system.

Considering the cost of raising a kid in America has been estimated at $20,813, or a combined $237,482, one can see why $7,500 is nice but is very much not going to cut it.

In case it needs to be said, I am paying quite a lot more than this to raise my three children. If you do not count taxes, they account for the majority of family expenses.

Anna North of Vox is the latest to interpret cash payment programs as failures. I continue to see the implied marginal costs as affordable, and like Robin Hanson I say one can simply pay more. Also pay more in the form of a lump sum, which is much more efficient than convoluted policies or increased leave that many do not even want.

Guarantees of maternity leave increases the measured gender pay gap, increasing the measured motherhood pay gap, and increased the likelihood of first children but decreased the chance of additional children. There is the note that without leave more women leave the workforce entirely, which decreases the pay gap as measured while increasing the real one. Based on first principles of economics this is not surprising. Once again, if you want to help out new parents, much better to give them money directly rather than trying to give them things indirectly, and let people find what arrangements work for them.

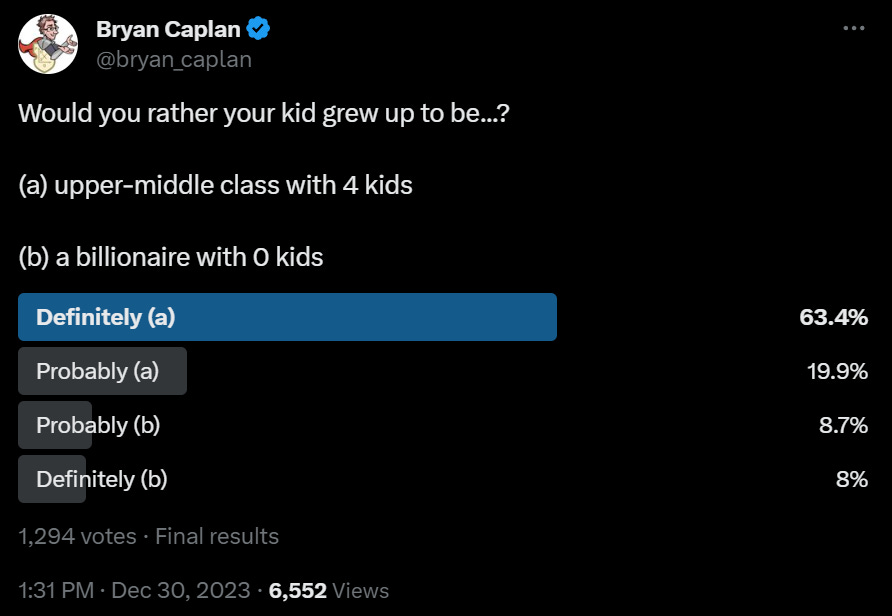

An absurdly biased sample, still worth noting.

My favorite response was from Adamas Nemesis, pointing out that you could likely use that billion to bankroll having a bunch of additional children. A strong case.

If we take the spirit of the question, however, and assume the billions are sterile, then I do think this is rather clear. Also a hell of a willingness to pay.

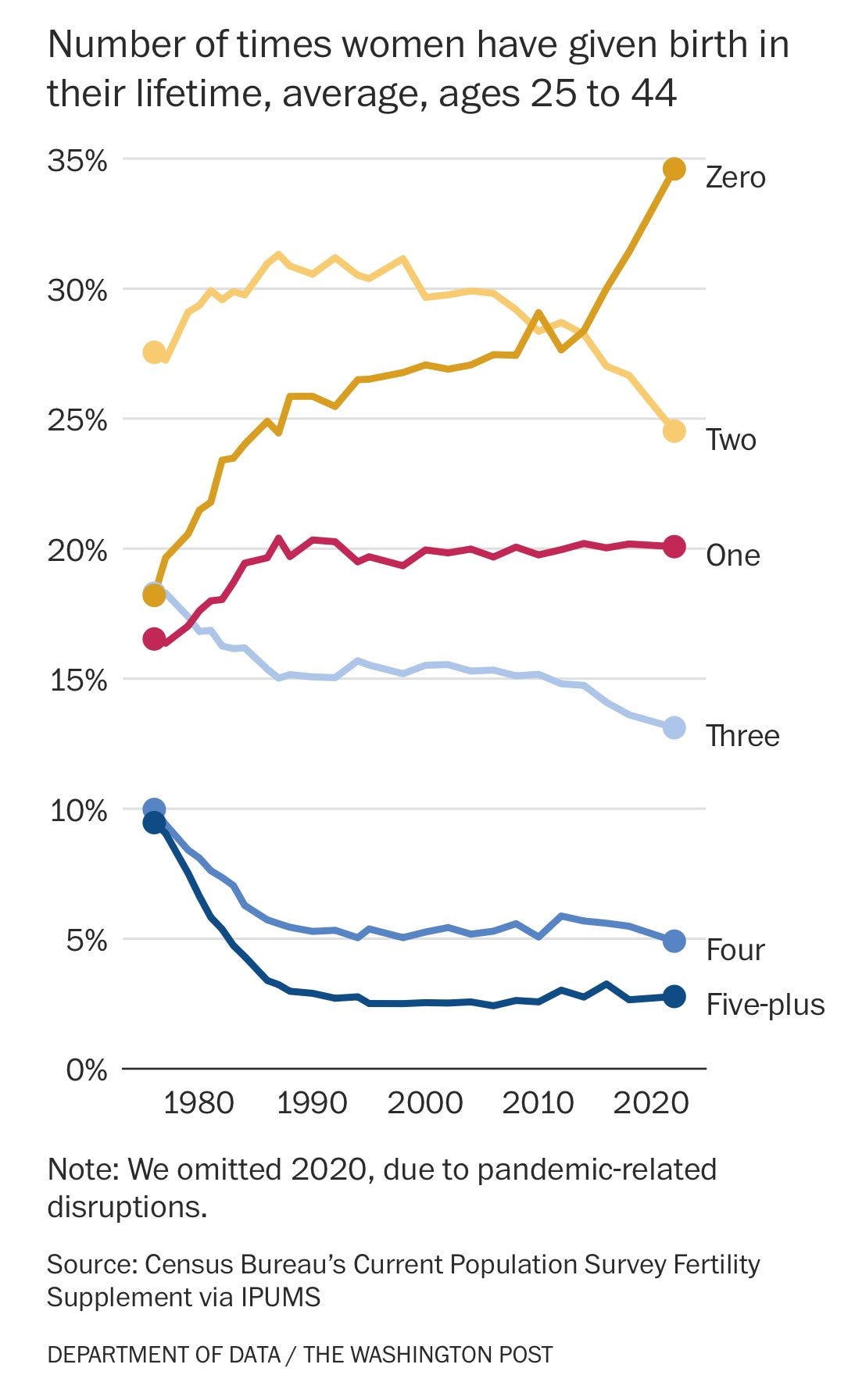

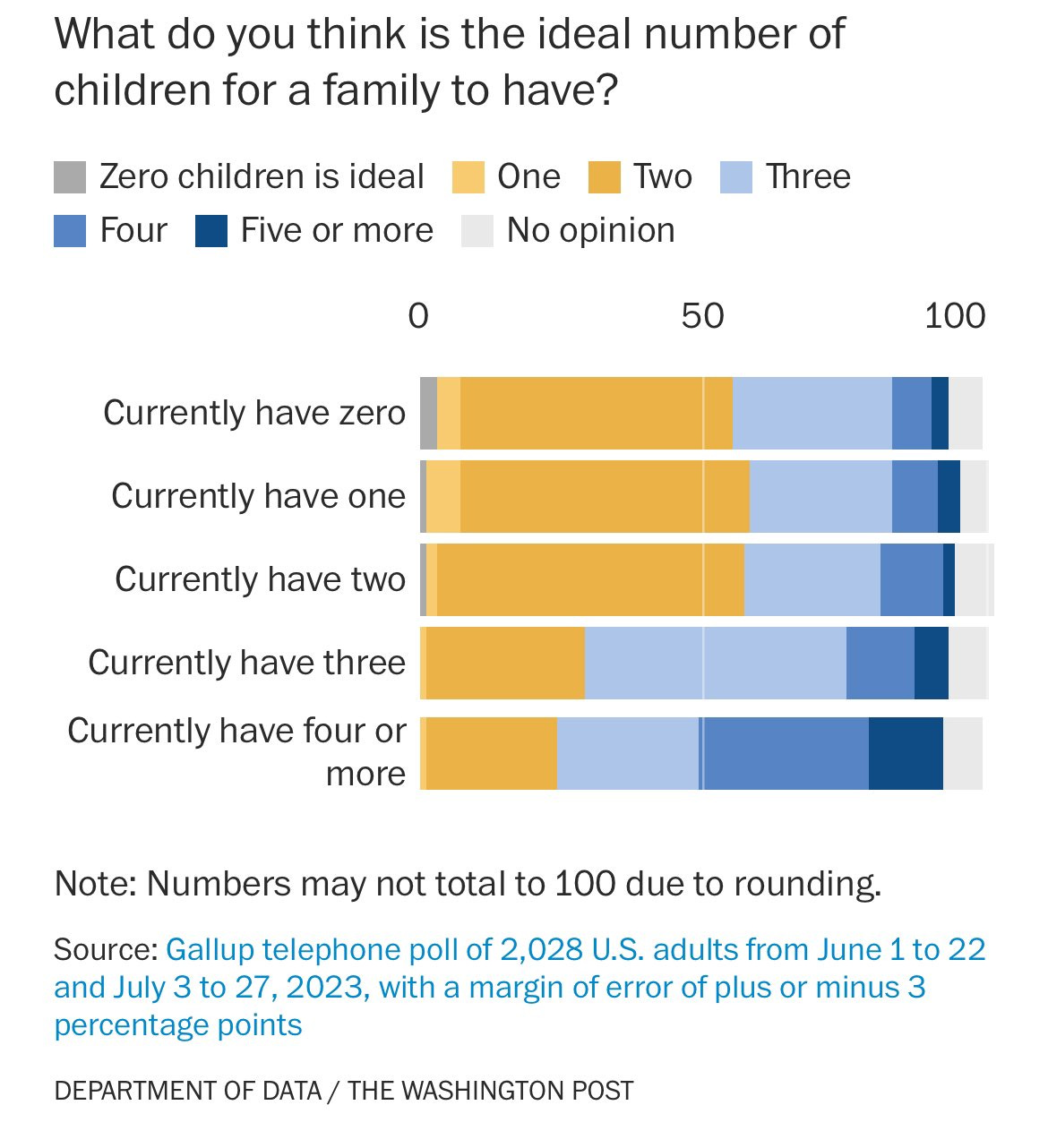

Miri Vinnie: We actually have data on this! And the answer is: not much Women who want kids generally want at least 2, thus the % of one-child families hasn’t changed at all in 30 yrs. But instead of having 2 they’re having 0. Most often because they don’t have anyone to have kids with.

Cartoons Hate Her: She’s right, and also, I don’t understand why the declining birth rate is seen as “women choosing to have fewer kids” when often women want more kids than their husbands do.

The way it works today is that the man wants X kids, the woman wants Y kids, and by default this means you get min(X,Y) kids. If you instead got Y kids, or avg(X,Y) kids, that would be a lot more kids. So would if people aggressively filtered to ensure X=Y, but too often we don’t prioritize that until very late in the game. And also of course if you don’t have a partner, or life circumstances don’t allow, or biology doesn’t cooperate, you can get less that way too.

You can also go big, and have 22 children, 21 born via surrogates, with 16 live-in nannies.

If you are fine with people choosing to have zero kids when it is an obvious mistake, and you want the human race to continue to exist, well then some people are going to have to have really quite a lot of kids, often in ways and for reasons that do not seem ideal. I am fine with it.

The affirmative case for surrogacy is simple. Life is good. People are good. More surrogacy means there are more people. Everyone involved is better off, most of all the baby.

The affirmative case for essentially every way to have more children is the same case. Life is good. People are good. Making those people be even better, is even better. The details are not so important.

Being pregnant, in many ways, sucks. It seems highly reasonable to pay money to avoid it, in a voluntary win-win trade. We shouldn’t have a stigma about this.

Amanda Askell: If I ever have kids, I want to have them via a surrogate because (a) I want to use my own eggs and (b) I don’t don’t want to be pregnant or give birth. This feels like a preference that is probably taboo but shouldn’t be.

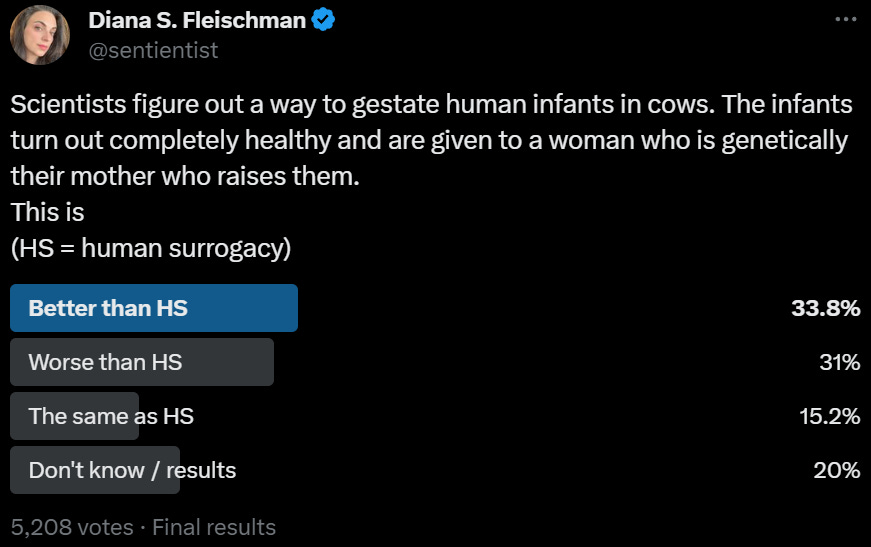

A fun scissor statement on the matter:

To me the answer is clear. That is part of what makes it a good scissor.

The transformative answers are coming. Eventually.

Max Novendstern: the most underrated technology right now: the capacity to generate egg cells from stem cells in arbitrary quantity + capacity to select for IQ among embryos means IVF will enable the selection of children with one-in-a-million IQ markers. this is not priced in.

Yes. When (not if, when) we gain the ability to do this, and do it sufficiently cheaply, not only do we remove practical age limits on fertility, we can also do arbitrary amounts of embryo selection.

Will a lot of people try to stop this from happening, treat it as some horrible thing? Yes, of course they will. Don’t let them stop it.

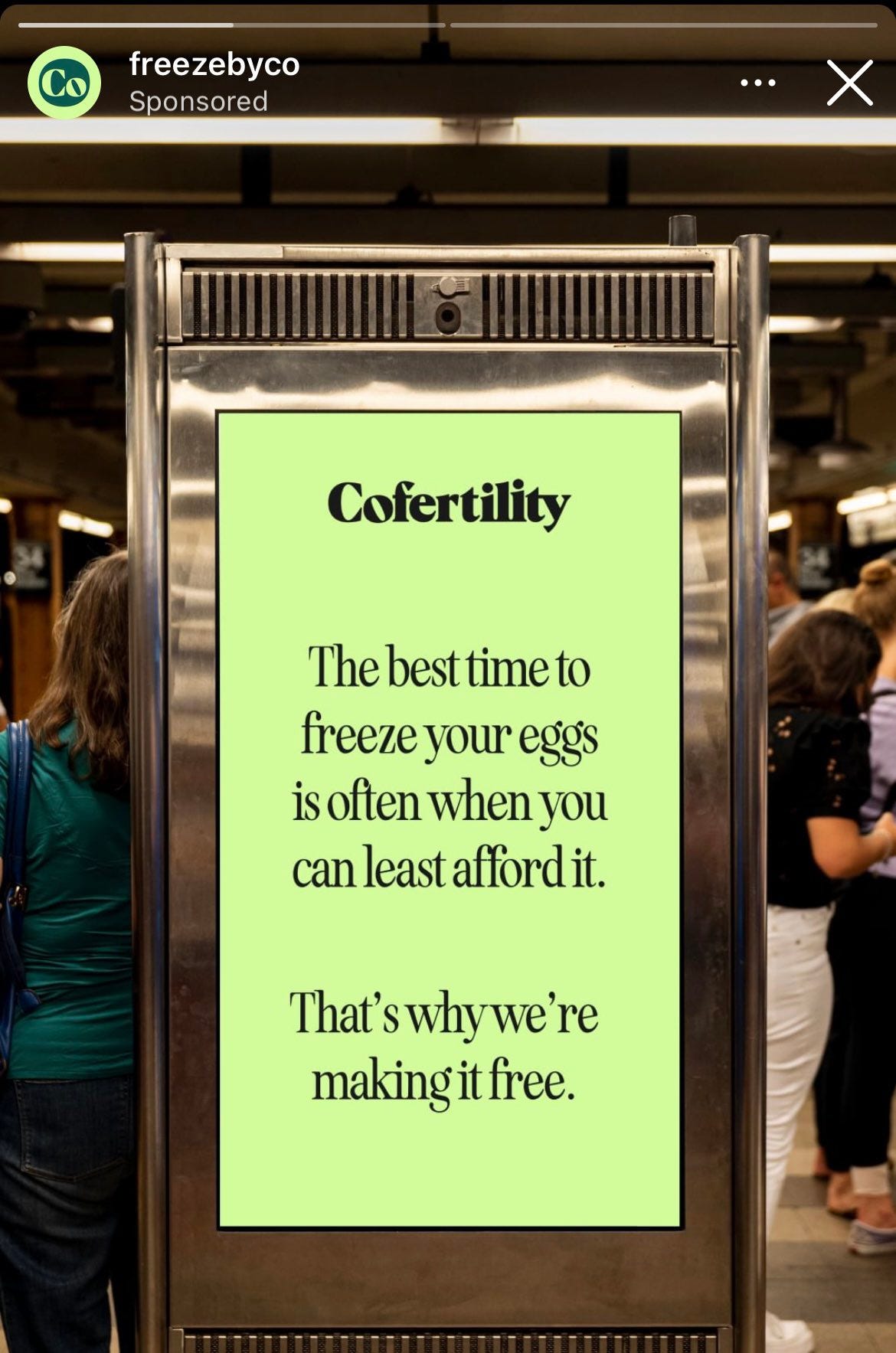

Cremieux: This is an interesting prospect. TL;DR: If you qualify, a company will freeze your eggs for free, but they keep half the eggs.

They sell them to people who need eggs to have children.

No monetary cost to you. This is a cute end run around the ‘we are not allowed to pay people for things’ problem.

How you think about it depends on how you think about egg donation. I am all for it. If someone else wants to raise my biological children, to me that seems like a win for everyone involved, especially the child. I did not donate (sperm) ‘when I had the chance’ but I notice I am sad about that.

7.4% of women who freeze their eggs go back and use them. Is that a good rate? It is all about cost versus benefit, risk versus reward. The frozen eggs are an insurance policy and an option. The value of having a child when you could not have otherwise had one is often very high. If you consider the all-in cost including storage as something like $25,000, then yes this is very much a rich society’s game to be playing, but the money seems well spent.

Robin Hanson attempts to recalibrate respect towards insular high-fertility cultures, based on his anticipation of their future dominance. Tyler Cowen would doubtless say that if respecting their practices is the goal, to stop watching documentaries and to travel amongst them, the Amish are only a few hours away. I would agree.

It is a strange project. I hope that it can be used as an illustration of how to view ‘right side of history’ arguments.

Often we are told that we should support that which we anticipate future people supporting, so as to be on the ‘right side of history.’ This can be long term reputational, so future people treat us kindly. It can be short term, keeping an eye on what the winners will reward and punish. Get on the winning team now, based on its arguments it will win in the future, and help it win now. This strategy is commonly employed throughout the political and social spectrums.

Certainly one should notice what features lead to success, or have what positive or negative impact. And one should update accordingly in various ways. What one should not do is automatically bow to our new insect overlords (or future AI overlords). We do not bow down. We definitely do not do it in advance.

How much should we respect the features of these insular cultures, if we believe the future is likely to fully go the extreme way that Hanson anticipates? One must evaluate the features case by case, look at what work they do in various ways, decide for one’s self where the important work is done and what is the best approach.

Hanson names several promising traits.

The most promising is that children and fertility begets fertility, especially happy children. Children do better with lots of other children to play with and a world that is built around them rather than shoving them off to the side. And the children in such cultures, Hanson reports, typically are happier than our children, despite materially having far less.

I mostly buy this. Our society is very bad at giving children independence and responsibility, giving them meaning and tangible things to do. Instead it is obsessed with the child’s progression through various hoops and requirements, making their lives, and those of the parents, a constant stream of stress. We do not need to do this. A radically different attitude towards children and raising children would go a long way. It is not obvious that this would not on its own, or together with modest other reforms to improve economic conditions, be sufficient.

What about the strong communal bond and lack of resentment of community obligations? That also seems promising. Communal bonds are great and we are doing a terrible job of creating or maintaining them. This does not require an extreme insular culture. We need to get on this too, big time.

What about the isolation, strong religion and restrictions on technology? They are necessary, under current conditions, to protect the valuable parts of the social technology from sustained attack across generations. Religion is also (among other things) a highly active ingredient in justifying extreme investment in community, and in tolerating a lot of quite inherently boring community and cultural obligations.

I believe this can be made to work without the extreme isolation, and with only relatively sane limits on technology, under current conditions. Whether current conditions sustain themselves under development of AI is of course another matter, but if everything transforms from AI (whether or not something good or better results) than questions of current fertility levels would become moot either way.

Robin Hanson offers My Fertility Posts. He has quit a lot of them. If you want to explore, I recommend reading them in order of publication, as it allows you to follow Robin has he thinks about the problem, establishes his perspective, then considers implications. It is quite a trip.

Brink Lindsey considers some implications of a shrinking world.

Scott Alexander welcomes twins, in the most Scott Alexander way all around. A wonderful, heartwarming piece if you know his work well.

A simple summary of much of the issue:

-

We used to shame ‘incorrectly’ having children via sexuality.

-

Then we stopped shaming sexuality. Which is good.

-

Also we used to shame not having children. Then we stopped doing that.

-

Which, again, is good, if you find other ways to still ensure there are children.

-

Except then we started shaming ‘incorrectly’ having children directly.

-

We have also continuously raised the bar on what counts as ‘incorrect.’

-

And we don’t much praise those who have children.

-

All of which is bad.

-

And means not enough kids.

-

Especially when kids make it hard to otherwise maintain social status.

We used to shame people too hard over too many and the wrong things. It is good that we do less of that, although in some cases (such as some forms of literal crime) we have clearly taken this too far. The problem is that the shaming we used to do mostly did have an underlying societal purpose.

And rather than everyone realizing shaming is bad and not to do it at all, we have substituted other forms of shaming and other social pressures.

The pro-social shaming, and pro-social judgments and status rewards, have been subject to unilateral disarmament. We took the pro-social versions down, letting the socially neutral and actively anti-social shaming and judgments run rampant in their place. At minimum, if we want to fix this, we will need to orient positive social status to those who do the things we want people to do more often, such as having children.

We could of course also throw money at the problem. And we should do that as well. But it will be a lot cheaper if we do both.

Cultural trends are about cultural trends.

Bryan Caplan: Conformity drives a lot of fertility behavior. The main driver of the Baby Boom really was, “Everyone else is having big families; we should, too.”

Which ironically means that publicizing Baby Busts probably makes them worse. See South Korea!

This should worry us when considering small interventions on the margin. But it should give us hope around large interventions, or interventions with broad cultural impact, and helps explain the many very large historical swings in fertility.

Cousins are vanishing as the birth rate declines, I would presume in practice even mores than the numbers would suggest, as our families become more disconnected. Cousins (and nieces and nephews) are a clear example of a positive externality that is not properly priced into people’s decisions. Cousins make us less alone, provide social support and connections and optionality. They do this at vey low cost, if a cousin is not relevant to your interests you can mostly ignore them.

We used to use various forms of social pressure to get people to do socially optimal things more often, now we do much less of that, and we have no plan to replace the effect.

If you don’t respect parents, people will be reluctant to become one.

Felicia Day: When someone at a function I don’t want to talk to comes up at me, I say I’ve decided to focus on being a parent for a while. They literally can’t leave fast enough.

This raises an obvious dilemma. If Felicia Day said that to me, do I take it as a sign she wants to leave me alone? Or do we get to happily geek out about kids? Because I would happily geek out with Felicia Day about kids, with or without also geeking out about lots of other things. DM me anytime.

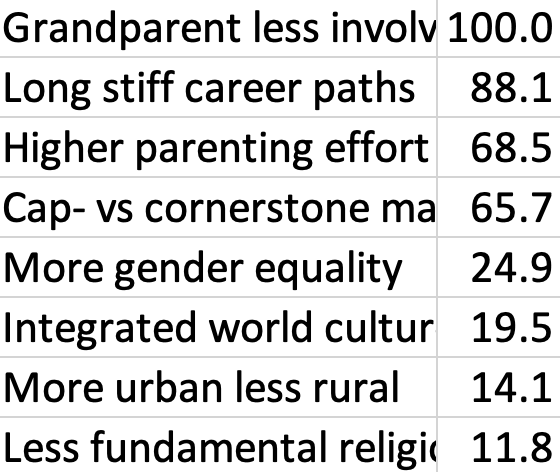

Robin Hanson asks, what trends need to reverse to help fix fertility declines?

Robin Hanson: The following 8 social trends plausibly contribute to falling fertility:

More gender equality – More equal gender norms, options, & expectations, have contributed to fewer women having kids.

Higher parenting effort – Expectations for how much attention and effort parents give each kid have risen.

Long stiff career paths – The path of school & early career prep til one is established worker is longer & less flexible.

Cap- vs cornerstone marry – Now marrying/kids wait until we fully formed, career established, then find matching mate.

Grandparent less involved – Parents once helped kids choose mates, & helped them raise kids. Now kids more on own.

More urban less rural – People now love in denser urban areas where housing costs more, kids have less space.

Less fundamental religion – Religion once clearly promoted fertility, but we less religious, especially re fundamentalism.

Integrated world culture – We pay less attention to local, and more to global, community comparisons and norms.

Here was the combined effect. I think this underrates high parenting effort and the influence of religion, but I can see a good case for career paths, cornerstones and grandparents as well. I am inclined to consider cornerstone more of a consequence or symptom than a direct cause, but this is not clear.

The ‘big four’ here are all rising costs. Higher effort required from you and less outside effort mean the direct costs are higher. Cornerstone approaches and stiff career paths raise opportunity costs.

As discussed under South Korea, gender equality is tricky here. If you get rid of other traditional values and norms around children and families, then more gender equality probably becomes actively good for fertility. The logic is simple: Once you give women the choice on how many children they have, otherwise treating them badly and giving them less opportunity is going to cause them to choose to have less children rather than more children. The way that older gender inequality promoted fertility was that it took that choice away from women. I hope we can all agree that giving them that choice was a good change.

Related and gated: China’s Female Revolt, how sexist violence killed the Chinese dream.

In some ways we return to tradition, but you might be wrong about what tradition is.

Jamie: My grandmother who was born in 1930 wants you all to know that there is no Return to Tradition. They constantly had kids out of wedlock, they just hid them. She said I should tweet that.

Constantly is a relative term. It is highly plausible, and I would think likely, that there are two equilibria, neither of which involves getting rid of out of wedlock births.

-

Maintaining norms against out of wedlock births, and minimizing how many there are, necessarily involves a lot of people choosing to hide out of wedlock births in various ways, but also a lot less such births overall.

-

Not maintaining those norms means you do not have to do that, but you get a lot more such births as a fraction of births.

Similar rules hold for many other behaviors, including much criminal activity. We have moved a lot of things recently from the first category to the second category. The hypocrisy and local misery and cruelty inherent in option one has not survived our greater awareness. Alas, often the second option is actually worse as an equilibrium.

One can also see this as a market failure. There is a wide range of behaviors that imposes externalities on society as a whole, that we want to happen less often, but which it is impossible to entirely eradicate. Our strategy used to be to punish such activities to reduce their frequency, even though this is locally destructive and resulted in worse local outcomes, and people paid costs to not get caught. This was not an ideal solution, but it was often still net positive when compared with the original market failure, and increasingly we are cutting down Chesterton’s Fence.

DINKs (double income, no kids) bragging about how they get to go on vacations and order both appetizers and desert and other neat stuff like that. I like to think you can see the hints desperation below the surface as they attempt to justify how they made good life choices, but not everyone is that self-aware.

Andrew Domalewski: every dual income no kids couple I know who isn’t having kids “because of climate change” constantly posts photos of their vacations around the world…

Again, we have a similar dilemma. If you are going to be DINKs either way, I do not want you to be unhappy, please do go around subsidizing the local restaurants and taking vacations and such and have a blast. However, the world where such people experience a bunch of existential angst and find the whole thing turning to ash in their mouths after a while is in the long run a better world.

Cultural trends can change. Here is one particular potential future trend maker:

Bryan Hobart: Feeling faintly annoyed that 1) someone is going to get management fees for a “baby boom” ETF that’s prepped to launch as soon as Taylor Swift announces she’s pregnant, and 2) I will probably not get around to buying Bright Horizons or Carter’s in advance of this.

What other public companies are most levered to birth rate?

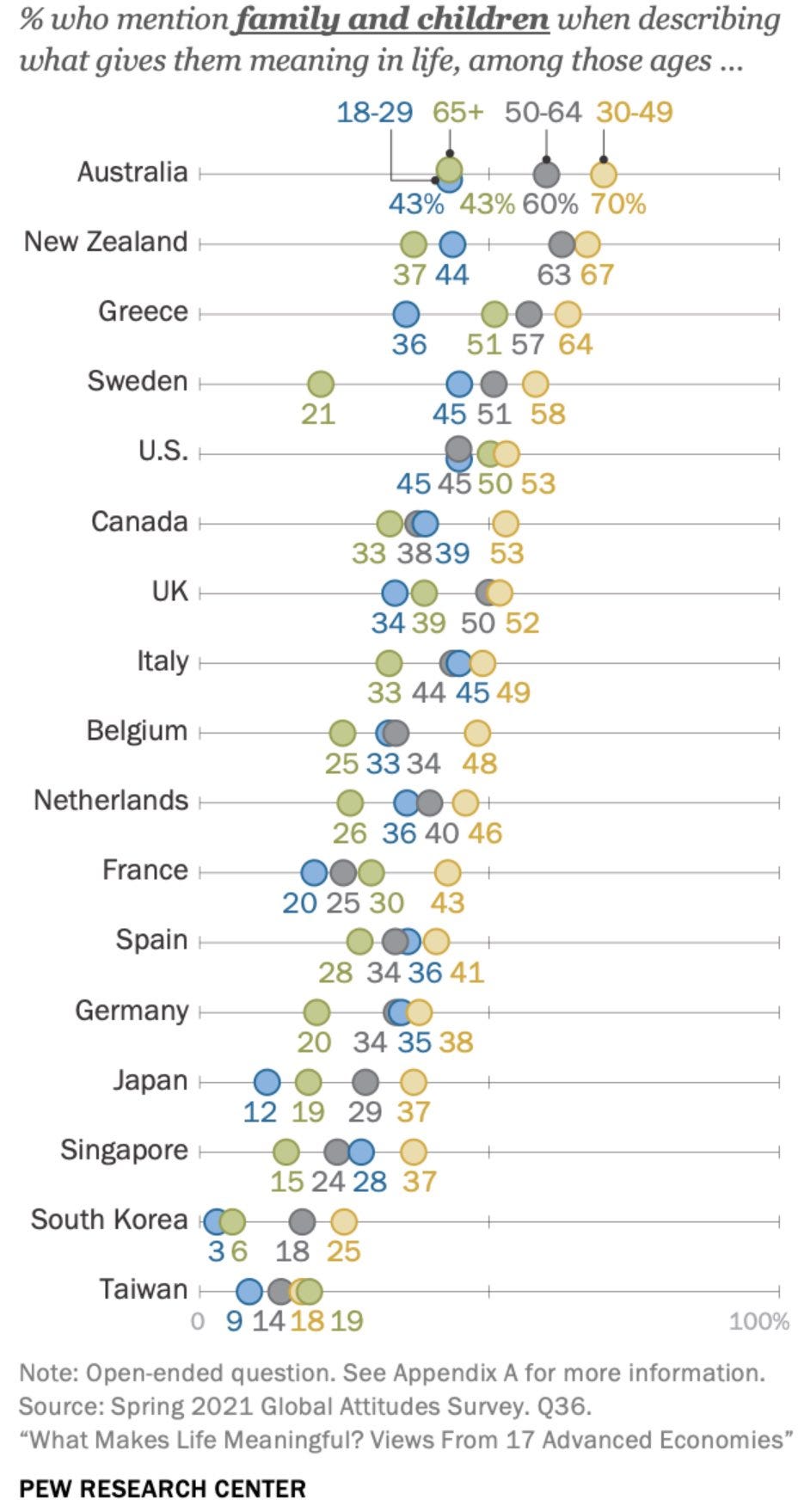

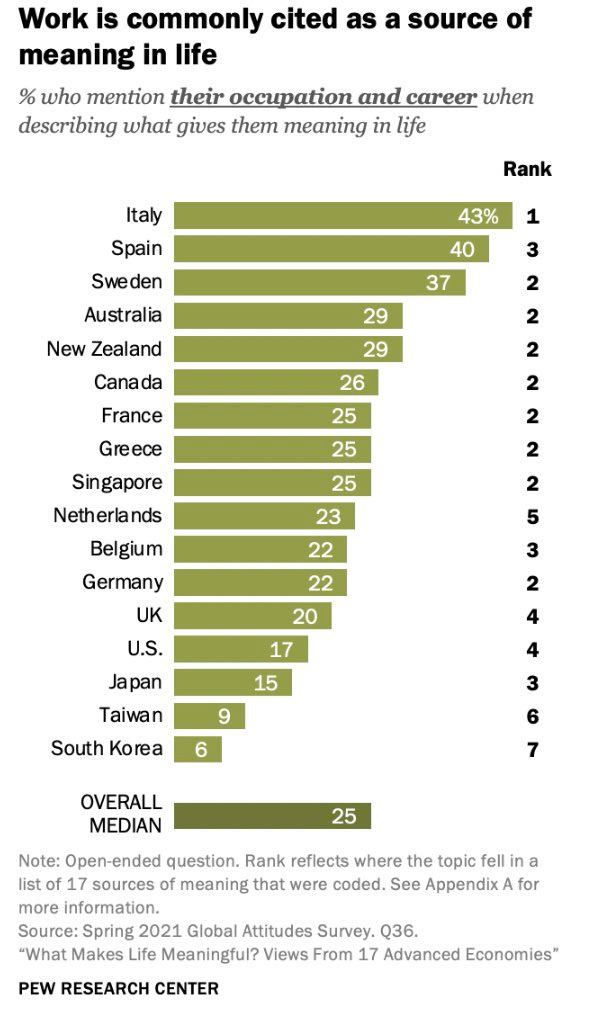

What percentage of people see family and children as a major source of meaning?

The numbers peak at 30-49, when people are raising kids. Sadly, the number falls away a lot for 65+, when one would hope that family and kids (and grandkids) would be a major source of meaning in one’s retirement. America seems to be doing a relatively strong job of not letting this fall off (and in Taiwan it actually goes up, but from an extremely low point). In Sweden it falls off a cliff. Perhaps this is variance. If not I would like to better understand the causes.

This is a two-way problem. We need people to find meaning in family, because people need meaning, and because it causes them to have and invest in families and children, which in turn will provide many things we need including more meaning.

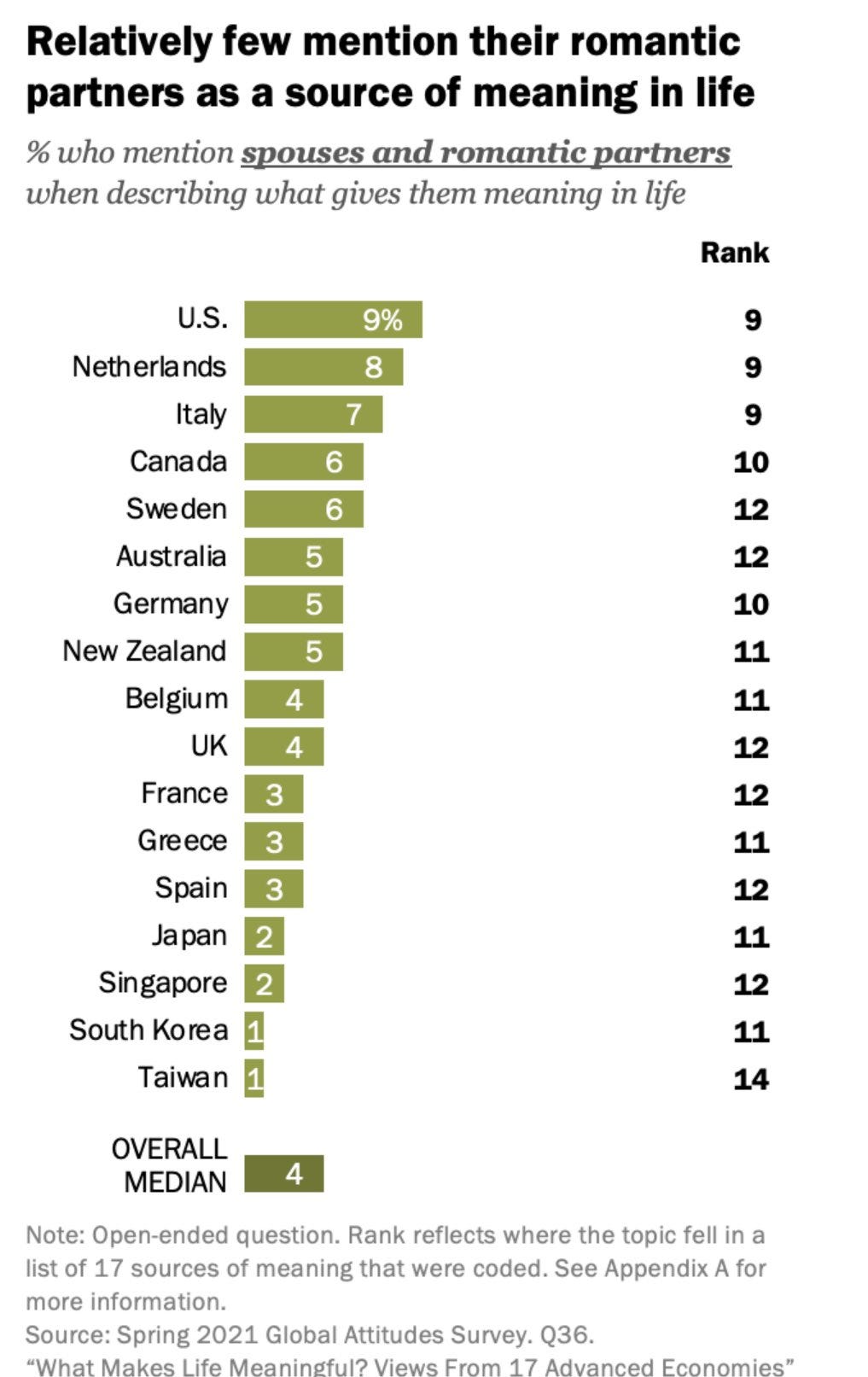

We also don’t have many fans of romance in terms of meaning, I am very surprised this is so low.

Alice Evans: Only 1% of Taiwanese emphasized romance. This tracks. I went to one mall and one supermarket today, there are no valentines. But there are thousands of celebrations of money.

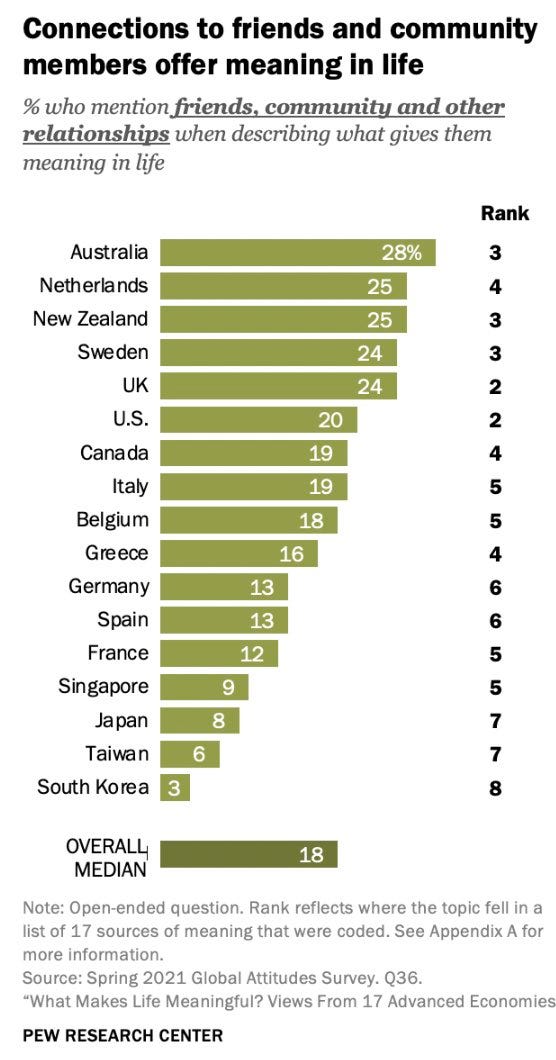

In a more general alarm category, all the numbers here are scary but also what the hell is going on in East Asia? They also don’t value friends and community, religion (the USA has 15% here, no one else is over 5%), work, hobbies or civic engagement. Looks like they simply lack almost all meaning.

I am sad we did not get China onto these charts, very curious where they would land.

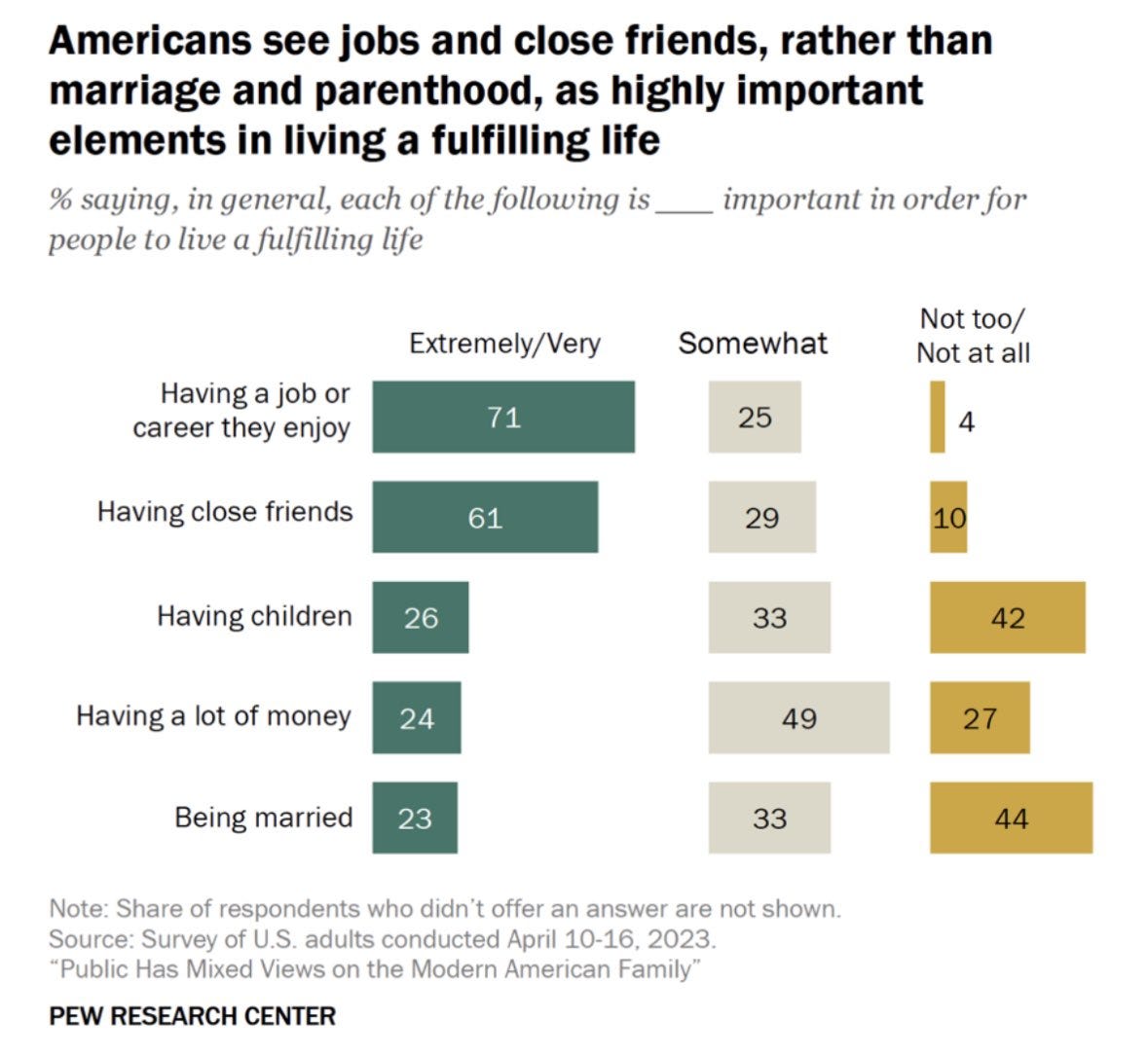

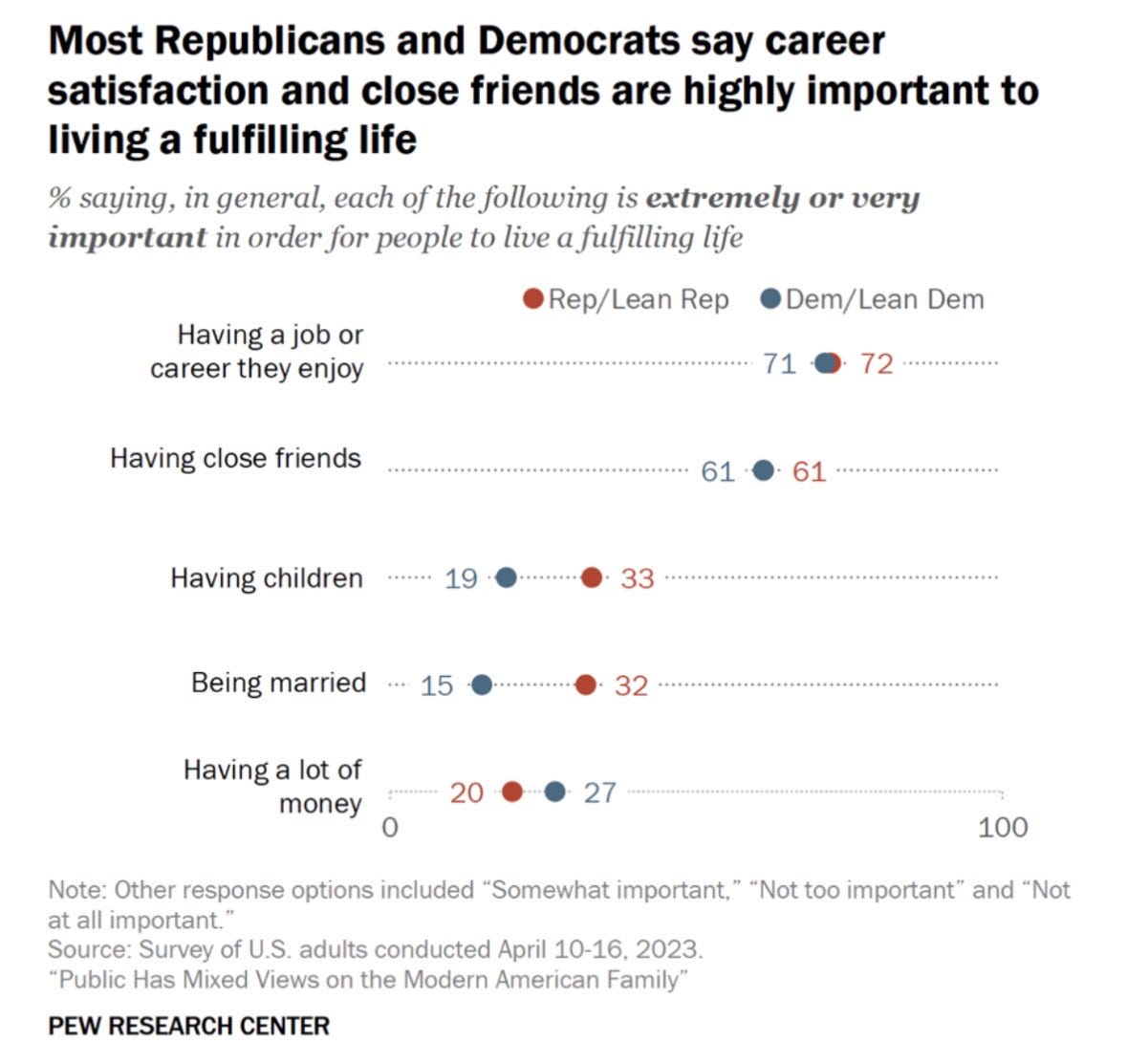

Americans across the board say that having a job or career you enjoy, or having close friends, is far more important than having children or being married.

I believe that Americans and similar people throughout the world are very, very wrong about this. Even on a pure happiness level, this is not what causes long term happiness. Ask your grandparents. In any case, this is obviously a huge part of the fertility problem.

It is actually rather stunning that the fertility problem is not vastly worse? If only 26% of people think having children is very important specifically to a ‘fulfilling’ life, you would think that would be vastly worse.

Thread pointing out that the trends around fertility are prone to frequent change. Female education or labor force participation, or family income, is a positive correlation with fertility one decade or century, then negative in another. There is no reason trends could not reverse themselves.

At minimum, what could we do about all this? Well, we could start by not letting the organization funded by literal Paul Ehrlich into our schools to show millions of our kids propaganda on how horrible it would be to have children of their own.

Paper says that India’s son preference is focused on desire to have at least one son, who can perform eldest son duties. That is enough for a large imbalance, and reduced family size is making this effect much larger. The paper doesn’t point to solutions. It considers cash transfers, but worries this would concentrate girls among poorer families. Which it clearly would, but you do get overall balance, matches still have to even out, and I don’t see a better alternative.

Aria Babu looks at correlations to ask what beliefs kill birth rates. Most things she looked at had little or no effect. The biggest effect was the percentage who agreed that ‘if the mother works, a preschool child is likely to suffer.’ Even then, the trend is not super strong, with a correlational effect size of 0.25 births per woman for no one versus everyone believing it, probably not entirely causal. Mostly this tells us that there is no one easy answer.

Rachel Cohen writes in Vox about motherhood dread. She paints a story where many moms are happy with their lives, or have egalitarian home arrangements, but they are afraid to tell anyone, whereas those who are dissatisfied complain loudly and proudly. It is okay to not be okay with motherhood, and not okay to be okay with it. So every woman gets filled with dread about the whole thing. Even if the underlying facts are happy, they have to feign unhappiness, which itself sucks. And of course, the financial and health burdens are immense. We used to sugar coat them, now we do the opposite. There is also complaining about inegalitarian gender norms at home, but even under theoretically ideal conditions that could only solve half of the problem.

Mostly it’s a lot of complaining, although with an attempted positive attitude, about the fact that everyone is constantly and exclusively complaining, whereas a positive attitude could go a long way. It makes clear that both the cultural and financial incentives are stacked against being a mother, both of which we will have to work to reverse. And more fundamentally, that we have let dread at the burdens of motherhood run rampant, while we work to suppress dread about growing old without children, dying lonely and leaving nothing as a legacy.