Legalize housing. It is both a good slogan and also a good idea.

The struggle is real, ongoing and ever-present. Do not sleep on it. The Housing Theory of Everything applies broadly, even to the issue of AI. If we built enough housing that life vastly improved and people could envision a positive future, they would be far more inclined to think well about AI.

What will AI do to housing? If we consider what the author here calls a ‘reasonably optimistic’ scenario and what I’d call a ‘maximally disappointingly useless’ scenario, all AI does is replace some amount of some forms of labor. Given current AI capabilities, it won’t replace construction, so some other sectors get cheaper, making housing relatively more expensive. Housing costs rise, the crisis gets more acute.

Chris Arnade says we live in a high-regulation low-trust society in America, and this is why our cities have squalor and cannot have nice things. I do not buy it. I think America remains a high-trust society in the central sense. We trust individuals, and we are right to do so. We do not trust our government to be competent, and are right not to do so, but the problem there is not the lack of trust.

Reading the details of Arnade’s complaints pointed to the Housing Theory of Everything and general government regulatory issues. Why are so many of the things not nice, or not there at all? Homelessness, which is caused by lack of housing. The other half, that we spend tons of money for public works that are terrible, is because such government functions are broken. So none of this is terribly complicated.

Matt Yglesias makes the case against subsidizing home ownership. Among other things, it creates NIMBYs that oppose building housing, it results in inefficient allocation of the housing stock, it encourages people to invest in a highly concentrated way we otherwise notice is highly unwise and so on. He does not give proper attention to the positives, particularly the ability to invest in and customize a place of one’s own, and does not address the ‘community buy-in’ argument except to notice that one main impact of that, going NIMBY, is an active negative. Also he does not mention that the subsidies involved increase inequality, and the whole thing makes everyone who needs to rent much worse off. I agree that our subsidies for homeownership are highly inefficient and dumb. A neutral approach would be best.

Zoning does not only ruin housing. Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour skipped New Zealand because there were not sufficient resource consent permits available to let her perform at Eden Park. They only get six concerts a year, you see.

With Pink’s two shows on March 8 and March 9 and Coldplay’s three shows on November 13, 15 and 16, it leaves Eden Park with only one concert slot this year. Considering the Grammy winner is playing seven shows across two Australian venues this February, Sautner says: “Clearly, this wasn’t sufficient to host Taylor Swift.”

…

The venue also needs to consider the duration of concerts in any conversations – as the parameters of Eden Park’s resource consent means shows need a scheduled finishing time of 10.30pm, something that may have been too difficult for Swift to commit to.

A short video making the basic and obviously correct case that we should focus on creating dense walkable areas in major cities. There is huge demand for this, supplying it makes people vastly more productive and happier, it is better for the planet, it is a pure win all around.

Jonathan Berk: “Only 1% of the land in America’s 35 largest cities is walkable. But those areas generate a whopping 20% of the US GDP.”

Wait, is that, yeah, I think it is, well I’ll be. Let’s go.

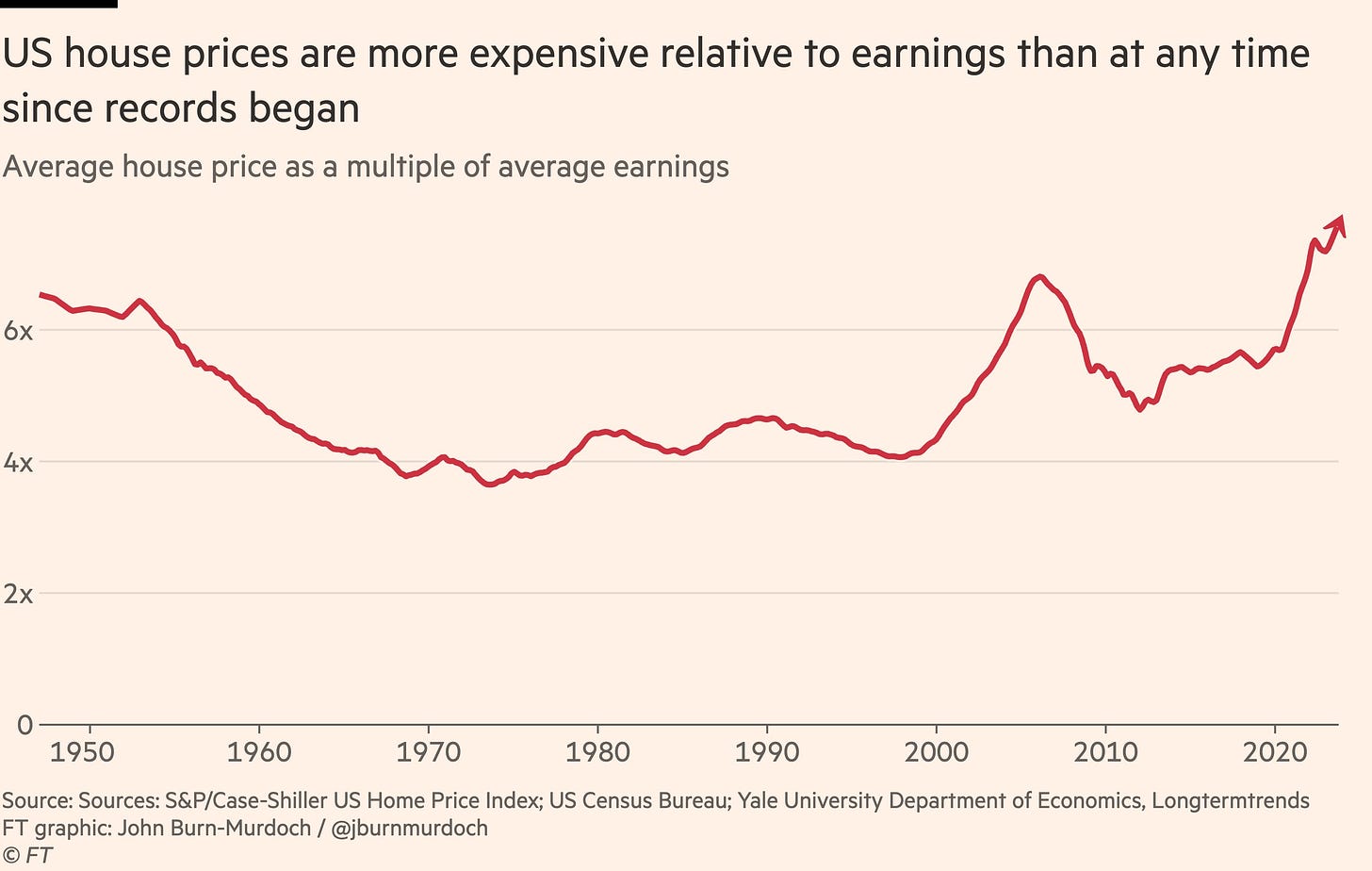

Elizabeth Warren: 40 years ago, a typical single-family home in Greater Boston sold for $79.4k—about 4.5X a Boston Public School teacher’s salary. Today, that home would go for nearly 11X what that teacher makes now.

We must bring down costs, which means we need more supply—plain-old Econ 101.

Elizabeth Warren: America is in the middle of a full-blown housing crisis. There are a lot of ways to measure it, but I’ll start with the most basic: We are 7 million units short of what we need to house people. What can we do? Increase the housing supply. It’s plain old Econ 101.

Exactly. We do not need specific ‘affordable housing.’ What we need is to build more housing where people want to live and let supply and demand do the work. So, Senator Warren, what do you propose we do to make that happen?

The actual proposal seems to be modest, allowing small accessory dwellings. Which is a great proposal on the margin, happy to support ADUs, but not where the real action could be.

Otherwise, prices are completely out of hand.

Jake Moffatt: Median home in California is 850k Median salary is 77k Even with 0 other debts, and a 200k down payment, you can only even get a loan for about 450k This isn’t gonna be addressed by people eating spam and white bread every day.

Matthew Yglesias looks at attempts being made in Maryland. On principle we have a robust attack on local control. In practice, the ‘affordability’ requirements that attach mean it likely won’t result in much housing. I agree with Matthew that we want the opposite, to maximize housing built for a given amount of local control disrupted. Even if your goal is to maximize only the number of specifically affordable units built, you still want to ease the burden on projects to the point where the project happens – as he notes, if you ask for 25% of units to be loss leaders, you likely get no building without a huge subsidy, if you ask for 5% you might get them.

Same thing with ‘impact fees’ and other barriers. If they are not doing any work other than throwing up a barrier, get rid of them. If they are doing good work (e.g. raising revenue) then you want to set the price at a level where you still get action.

Nolan Gray: This is the most potent zoning reform framing, and why YIMBY has been more successful than previous efforts: Most people live happy, normal lives, oblivious to zoning. When you point out that things like duplexes or townhouses are illegal, it shocks many into action.

It also makes sense that one can start with the basics, like pointing out that duplexes are illegal in most places, rather than starting with a high rise. Many don’t know. Others of course know all too well, but duplex construction has broad popular support.

Detroit may be going Georgist. Faced with so much unused land, they propose lowering the property tax from 2% to 0.6%, while raising the tax on the underlying land to 11.8%. Never go full Georgist, one might say, so will this be full or more-than-full Georgist? A per-year tax of 11.8% of value is quite a lot. Presumably the way the math works is that the value of the land gets reduced by the cost of future taxes, which should mean it decline by more than half, while the additional value of built property goes up as it is now taxed less than before. It seems good to turn over the land quickly, so perhaps charging this much, well past the revenue-maximization point, isn’t crazy?

If you let people build minimum viable homes to house those who would not otherwise have anywhere to live, outright homelessness is rare. Mississippi is poor but has very little homeless. NYC had close to zero homeless in 1964. We could choose to cheaply provide lots of tiny but highly livable housing, which would solve a large portion (although not all) of our homeless problem, and also provide a leg up for others who need a place to sleep but not much else and would greatly benefit from the cost reduction. Alas.

Rebecca Tiffany here attempts to frame building more housing as the ultimate progressive cause. Which it is, due to the housing theory of everything.

Rebecca Tiffany: Communities should be designed for 12 year olds & senior citizens who no longer drive & people using mobility aids to be able to comfortably & safely get around without a car or driver – to all of their daily needs.

Also we should build so much housing that an 18 year old trans kid can move out from unsupportive family member’s homes into a micro apartment or rooming house with a barista job. Those economic dynamic used to be the norm & we need to build that way again.

We need so much housing that a domestic violence victim or just a woman who is done with mistreatment can get an entry level job & quickly get a small, safe apartment for themselves & their kids.

A lot of ppl think they’re fighting for the disadvantaged when actually, they’re just vaguely fighting against broad categories like ‘landlords’ & ‘developers’. Lots of slogans, zero policy. If we’d redirect our energy to just fighting to get volumes built, we’d see stabilization.

In every market where there are more homes than people seeking housing, it becomes quickly affordable. The inclusive city can only be built on this understanding that a LOT of newcomers will flood everywhere desirable for the next decades.

Fighting against infill means you’re fighting FOR the destruction of farmland & forests. Fighting against densification means you’re fighting FOR suburban/corporate/car-centric lifestyles.

The inclusive city isn’t frozen -it’s dynamic, constantly changing. It’s designed for the newcomer, the ppl w/o assets, the young adult with big dreams, the artists, the elderly. Car infrastructure &limited zoning kill off the vitality of what makes cities beneficial to the whole.

All true, the question is does such rhetoric convince anyone?

Scott Sumner emphasizes how much more destructively regulated so much of our lives has gotten since 1973, and that this is likely a central cause of the productivity slowdown (‘great stagnation’) that followed.

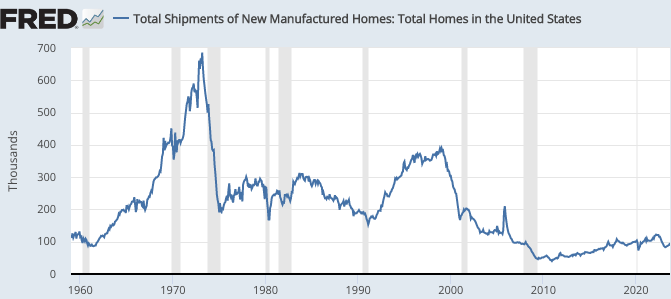

One specific note is that 1973 is when we prohibited manufactured homes from being transported on a chassis and then placed on a foundation, killing the industry, as detailed in this (gated) post by Matthew Yglesias:

He highlights that there is a new bill in Congress to repeal this and other deadly restrictions. We would still have to deal with various zoning and building code rules as well if we wanted true scale and for manufacturing to be able to cross state lines, but this would be an excellent start.

Longer term, Balsa will hopefully be exploring and pushing these and other Federal housing opportunities as its second agenda item. Standardizing building codes seems like excellent low-hanging fruit. Standardizing zoning would be even better.

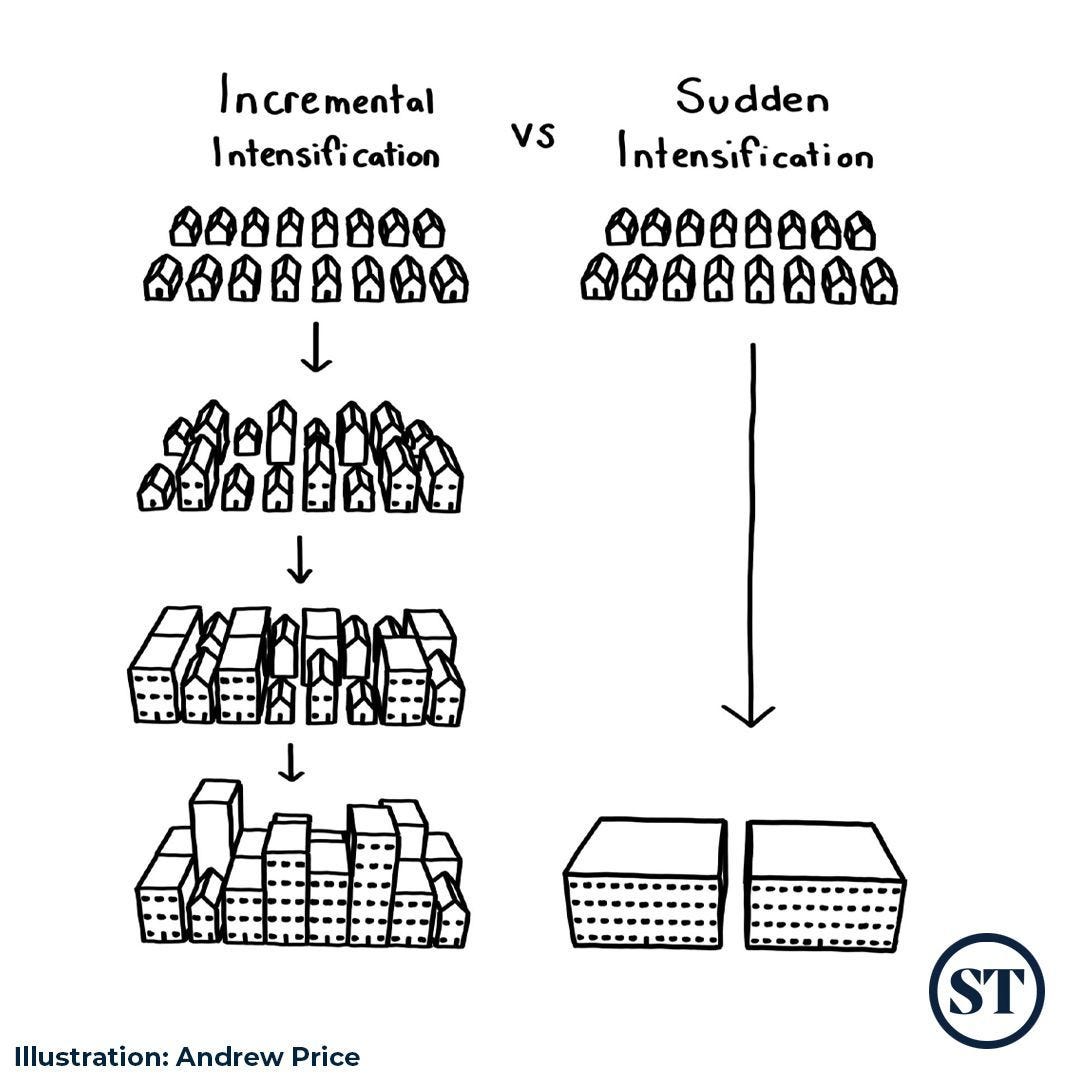

Strong Towns: If we want more than a bandaid on the housing crisis, the next increment of development should be legalized by right, in every neighborhood across North America.

Emmett Shear: This is a brilliant compromise. By-right construction throughout the US, but only one incremental step denser each time. Ensures change is possible broadly, without causing massive disruption. Of course you’d still be able to permit bigger change, but one step by right.

This will of course lead to some highly silly situations, in which the right thing to do is build house A, tear it down to build B, then tear that down to build C, and so on. Presumably you want some sort of minimum pause in between. I do like that this gives an additional incentive to move up at the first opportunity. Also a lot of very temporary housing is going to get built, but my guess is that is a minor cost, and hey it creates jobs.

How much do government regulations raise the cost of new homes? In many cases, infinitely, because they make the home illegal to build at all. Even when that is not true, the cost remains high:

Shoshana Weissmann: @GovGianforte stresses he focused on supply issues. Apparently government regulations account for 40% of the cost of a new home. Permitting delays raise prices. He streamlined permitting by helping builders apply to a growth plan tags already gone through public hearings

NotaBot: 40%! I knew that individually, a some reforms like removing off-street parking requirements could lead to big cost reductions, but this is wild. Represents a huge opportunity to make housing more affordable, if elected are willing to prioritize housing over other concerns.

Misinformation Guru Balding offers us a thread explaining how much American government, and especially liberal American government, acts as a barrier to ever building anything, from buildings to clean energy projects.

A paper by Alex Tabarrok, Vaidehi Tandel and Sahil Gandhi, Building Networks, finds unsurprisingly that when there is a change in local government it temporarily slows down development in Mumbai, India. Delayed approvals explain 23% of the change. Part of this is the obvious bribery and corruption ties that need to be renewed. The harmless explanation is that you were planning on building whatever the current government approved of building, and now that has changed, and also the change in government interrupts all the work done towards approvals and some of it needs to get redone.

Study offers new measure of regulatory barriers and their impacts.

Abstract: We introduce a new way to measure the stringency of housing regulation. Rather than a standard regulatory index or a single aspect of regulation like Floor Area Ratio, we draw on cities’ self-reported estimates of their total zoned capacity for new housing.

This measure, available to us as a result of state legislation in California, offers a more accurate way to assess local antipathy towards new housing, and also offers a window into how zoning interacts with existing buildout. We show, in regressions analyzing new housing permitting, that our measure has associations with new supply that are as large or larger than conventional, survey-based indexes of land use regulation.

Moreover, unbuilt zoning capacity interacts with rent to predict housing production in ways conventional measures do not. Specifically, interacting our measure with rent captures the interplay of regulation and demand: modest deregulation in high-demand cities is associated with substantially more housing production than substantial deregulation in low-demand cities. These findings offer a more comprehensive explanation for the historically low levels of housing production in high cost metros.

This makes sense. Permitting lots of supply is not effective without the demand. If you have the demand, what matters is what can be supplied, which this measures.

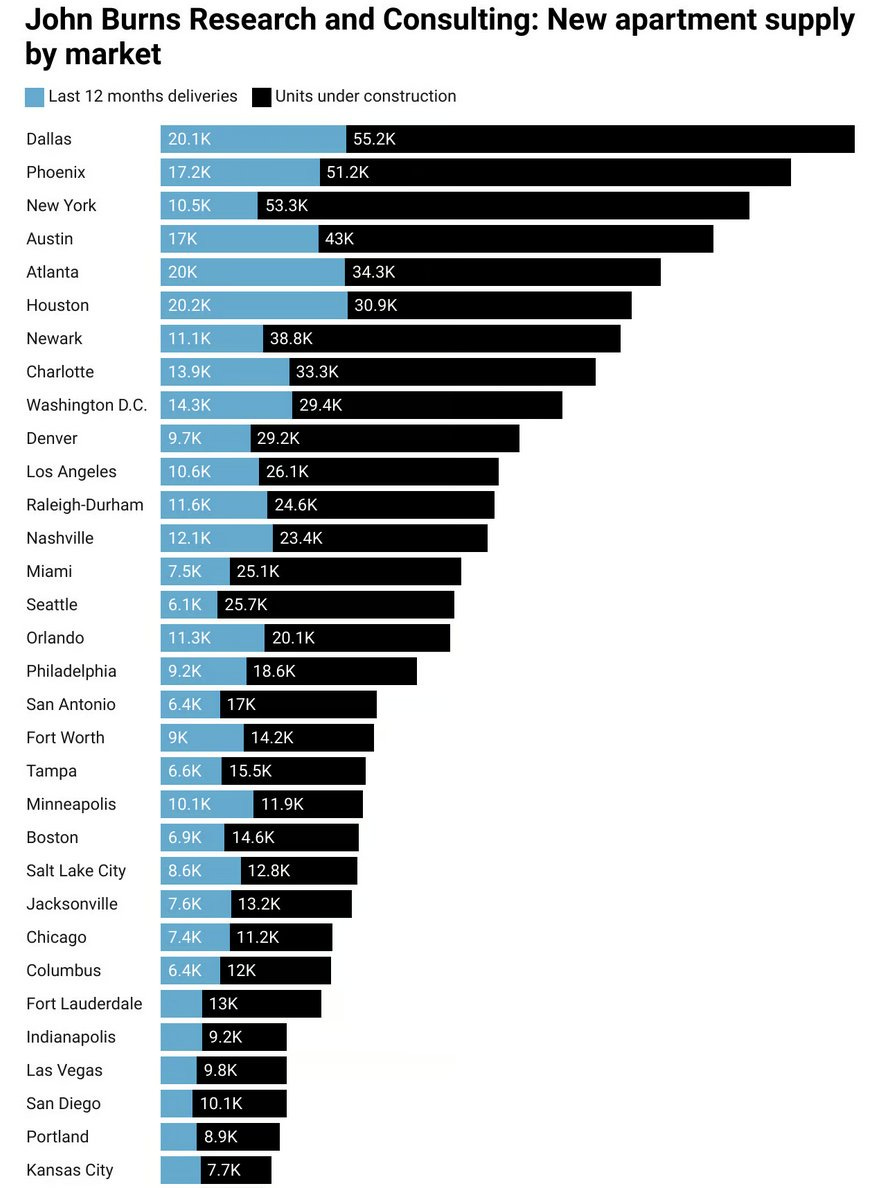

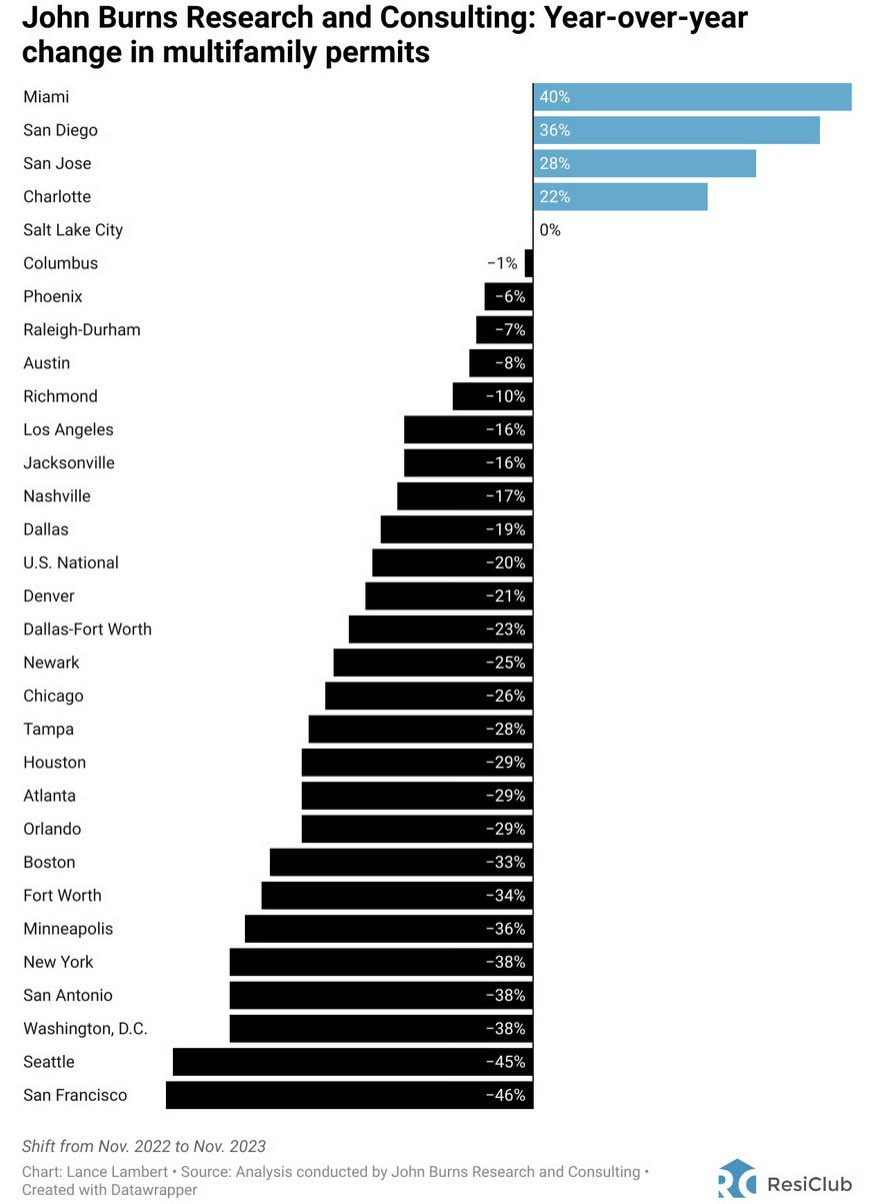

Multifamily housing will come online in large quantities soon, which is great. However it looks to have been a zero interest rate phenomenon. Which is presumably why do we look so unable to keep this up afterwards?

Cooper McCoy: A wave of multifamily supply is coming this year. These housing markets will see the most. JBREC: “While 2024 and 2025 should be the busiest years on record for new apartment construction and deliveries, the pipeline will thin out after that” A significant amount of multifamily supply, financed during a period of ultra-low interest rates during the pandemic, is set to come online this year.

However, the impact of this influx of apartment supply won’t be uniform across all markets. Recently, researchers at John Burns Research and Consulting published a paper finding that the biggest multifamily unit pipelines can be found in…

(1) Dallas (55,212 units) (2) New York (53,330 units) (3) Phoenix (51,208 units) (4) Austin (42,986 units) (5) Newark (38,809 units) (6) Atlanta (34,250 units) (7) Charlotte (33,309 units) (8) Houston (30,893 units) (9) Washington D.C. (29,359 units) (10) Denver (29,164 units)

Cooper McCoy: However, beyond 2024 and 2025, multifamily competitions will begin to decelerate. “While 2024 and 2025 should be the busiest years on record for new apartment construction and deliveries, the pipeline will thin out after that. We expect the surge in housing apartment construction to be temporary,” wrote Basham at JBREC. Basham added that: “Current permitting numbers [see chart] suggest development will slow once the current wave delivers. As interest rates rose and apartment fundamentals softened, financing for new apartment developments evaporated.”

There is still plenty of eagerness to build housing in the places people want to live, if it were further legalized. But with only marginal opportunities available, and the need to account for long delays and additional costs, the higher interest rates are going to sting.

Could they be getting reasonable again?

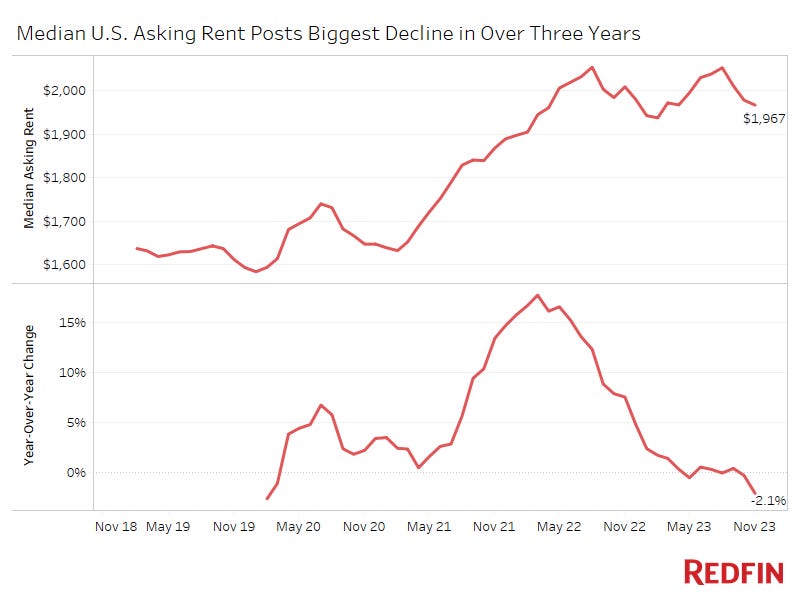

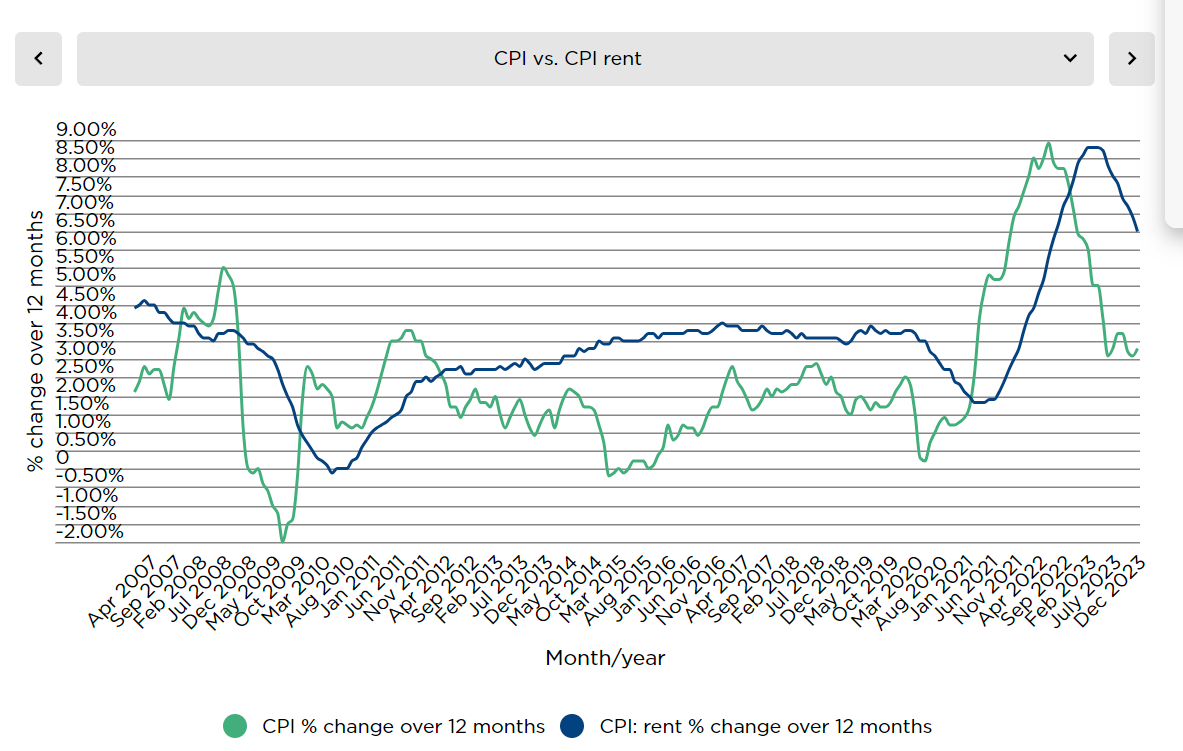

Alyssa Vance: Apartment rents are going down. Adjusted for overall inflation, rent is actually slightly cheaper than in 2018

Daniel Parker: Wouldn’t be surprised if this is mostly caused by people moving from places where rent is crazy high to places where it is more reasonable.

Inflation-adjusted is the watchword, but so I presume is composition, and this chart is easy to find but highly misleading.

I went searching some more, and here’s NerdWallet:

Rent growth has declined since its peak. Overall rent price increases have slowed down since a February 2022 peak of 16% and remain lower than pre-pandemic rates, according to Zillow. Year-over-year rent growth ranged between 4.0% and 4.2% throughout 2019.

Rents average $1,957 across the U.S. Typical asking rents in the U.S. are 3.3% higher than at the same time last year.

That seems far more sane, comparing the same metro area to itself over time.

That pattern makes a lot more sense.

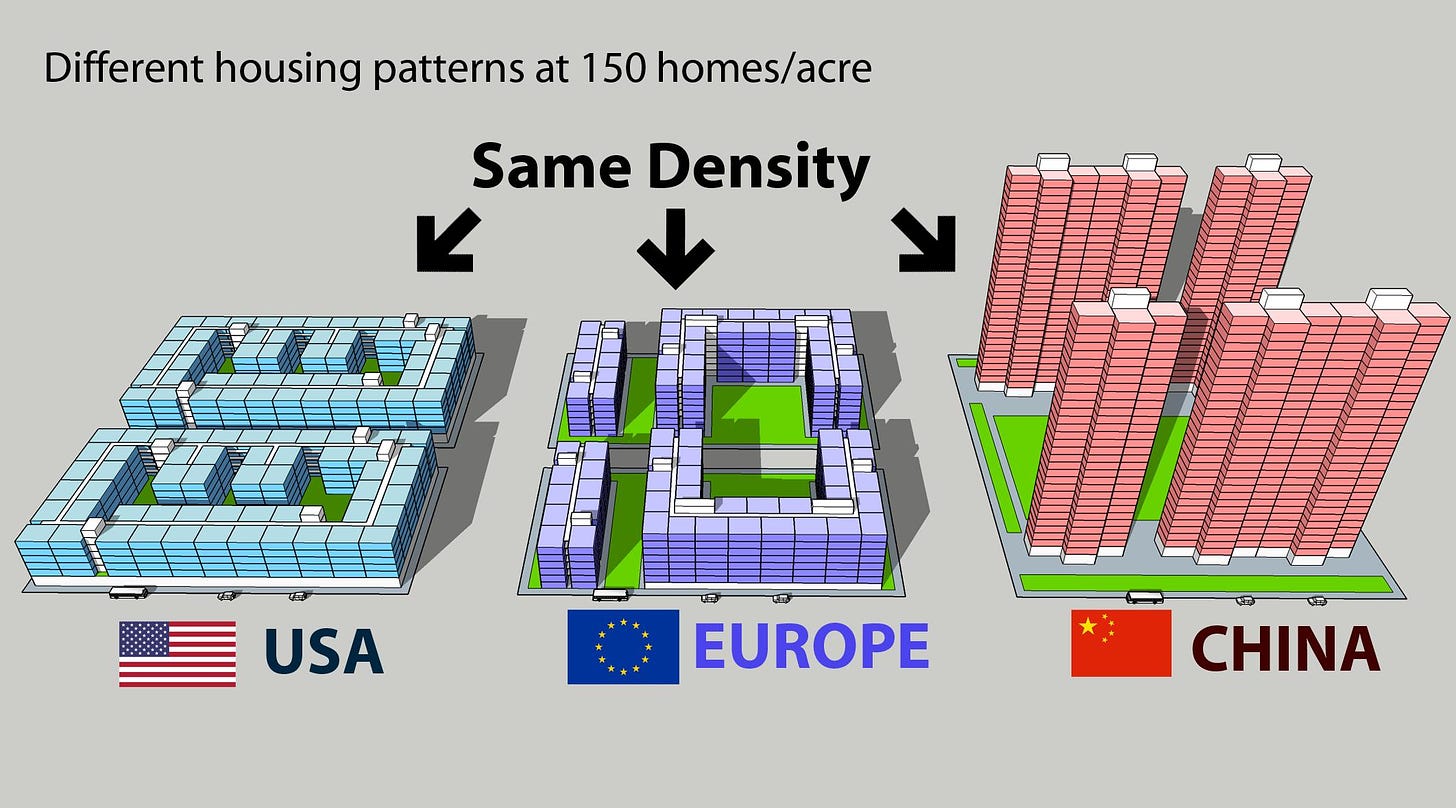

Alfred Twu: Density of new housing in the US is similar to China. While the 30-story towers look impressive, the 6-story buildings popping up throughout American cities are more efficient. Both have around 150 homes per acre.

How did the US and China end up building the same density so differently? In the US, height limits of wood construction, zoning, and urbanist design guidelines create buildings that fill the block.

In China, buildings are made of concrete, and there is a premium for south-facing units and green space. Zoning allows taller heights, but still has density limits, and so the result is towers in the park.

So, why do Chinese cities have higher population density than American ones? Suburbs. While China does build oneplexes (they call them villas), these take up a much smaller fraction of the land, vs. American cities where 75% of land being oneplex-only is typical.

[More great detail in the thread, I especially loved the detail about ‘transferable development rights’ in NYC where landmarked buildings can literally sell their zoning height.]

Frye: A unique aspect of American apartments is how little light and air each unit gets half of the units on the left will never receive direct sunlight! Asian-style tower apartments don’t have internal hallways, so there’s always light on two sides. And you can cross ventilate.

Emmett Shear: What’s great about 6 story buildings vs 30 story buildings is that they offer a lot more commercial street-level frontage, which makes walking around much more pleasant and productive. “Towers in the park” does not objectively seem to produce good neighborhoods.

My guess is that America got this one essentially right, and China got it wrong, although neither country did it for the right reasons. The Chinese advantage in light and views is nice.

But I think Shear’s note is very important here.

I don’t have the lived experience with it, but if you have a ton of green space and a few large towers, then a lot of people are effectively farther away from street level, and with so limited a supply of ground floors you are not going to get interesting areas with lots of opportunity. Our approach is also cheaper. The American mistake seems better than the Chinese mistake.

There are rapidly diminishing marginal returns to green space. I am very happy to have a small park very close to us to walk around. It would indeed be really cool to be right by a larger one, especially something as well-designed and expansive as Central Park. But once you have a very close playground and tiny walkable green area, and one reachable large park, additional public green space seems of relatively little value, mostly serving to create more distance.

My guess is a synthesis is best. New York actually does a version of this very well, except our density is not high enough. You want enough parks and green space so everyone has some available. You want the majority of the space to be taken up by relatively small buildings that are 6 or 12 (or eventually 24?) stories, often but not always with storefronts. And then you want a bunch of taller buildings as well.

It makes sense to have a non-zero number of buildings designated as landmarks. I would however choose zero landmarks and take our chances (and allow those who care to buy the buildings in question, including the city, if they disagree) if the alternative is the current regime, this is ridiculous:

Sam: my coldest take is that every single surface parking lot in Manhattan should be replaced with high rise apartment buildings this specific parking lot in lower Manhattan was designated as a “historic landmark” for decades, preventing housing from being built.

they were trying to build mixed income housing here for years and were held up due to the fact that the parking lot was a “historic landmark”

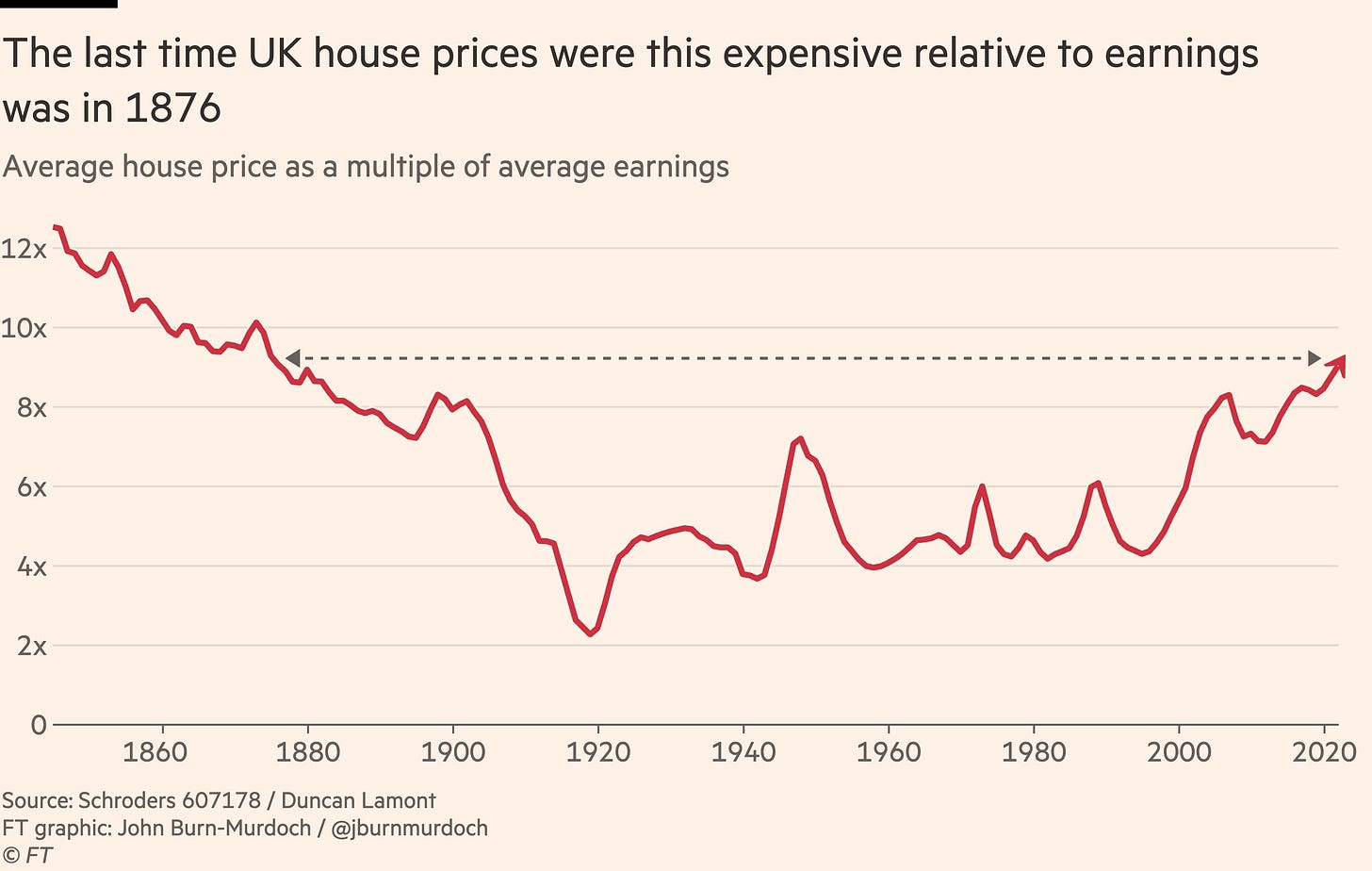

John Burn-Murdoch shows us how historically expensive housing in the UK is getting.

John Burn-Murdoch: NEW: we don’t reflect enough on how severe the housing crisis is, and how it has completely broken the promise society made to young adults. The situation is especially severe in the UK, where the last time house prices were this unaffordable was in … 1876.

My column this week is on the complete breakdown in one of the most powerful cultural beliefs of the English-speaking world: that if you work hard, you’ll earn enough to buy yourself a house and start a family.

The last time houses were this hard to afford, cars had not yet been invented, Queen Victoria was on the throne and home ownership was the preserve of a wealthy minority. After ~80 years of homeownership being very achievable, that’s what we’ve gone back to.

It’s a similar story in the US where the ratio of prices to earnings has doubled to 8x from the long-term trend of 4x. To state the obvious, in both countries last time houses were this difficult to afford homeownership rates were much, much lower than today.

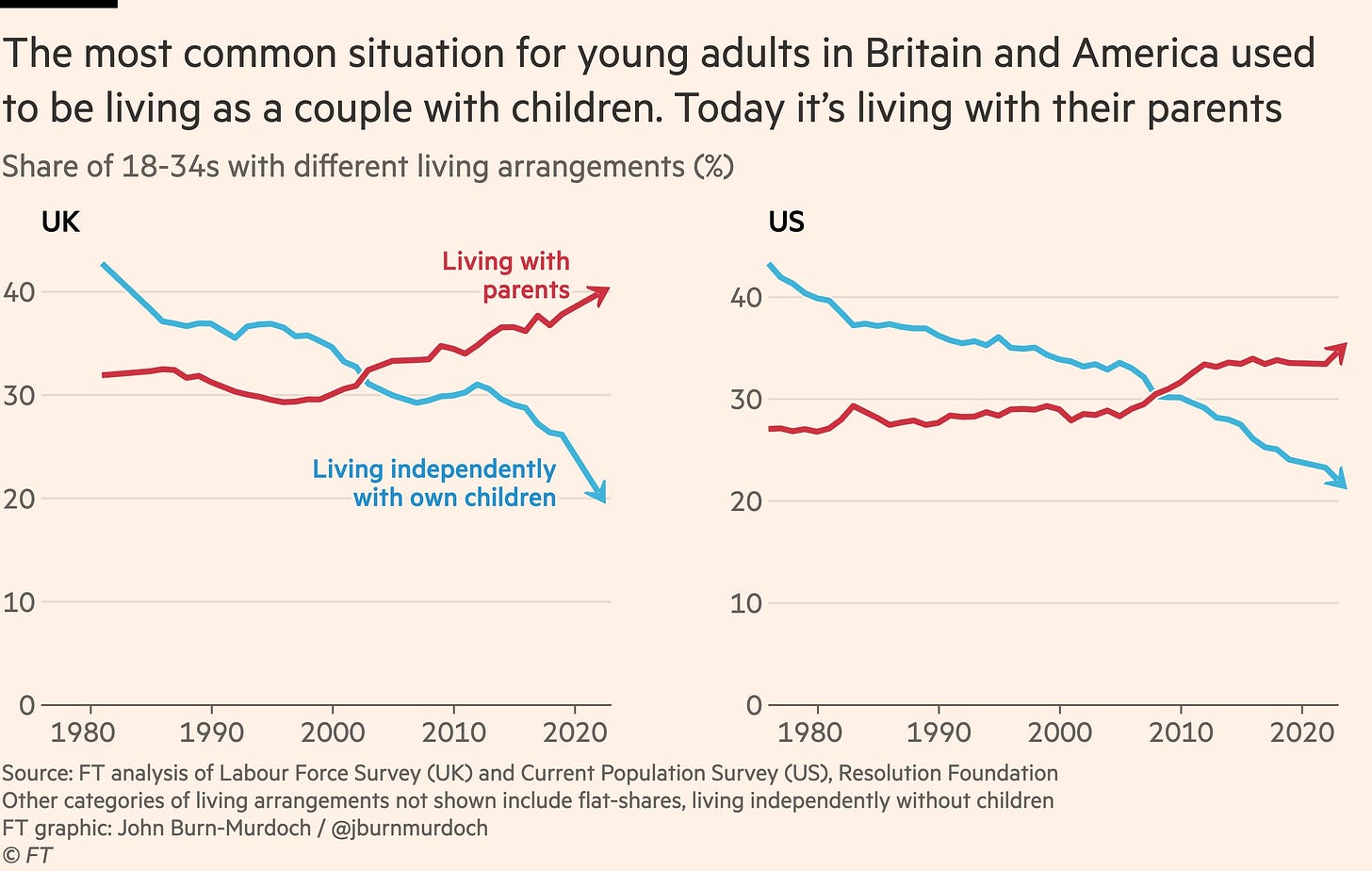

This has significant knock-on effects. In both Britain and America, the most common situation for young adults used to be living as a couple with children. Today it’s living with their parents.

Note that the scales in the first two graphs are distinct.

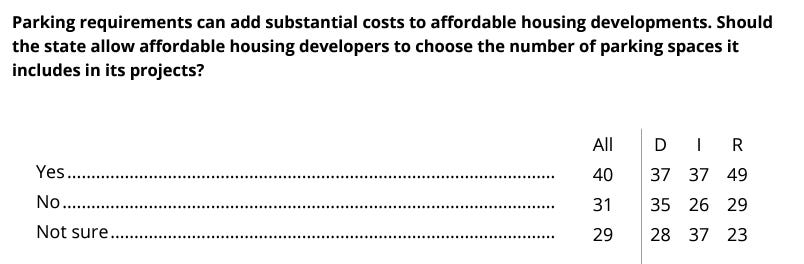

From a New York survey that was primarily about everyone disliking AI and supporting AI regulation, we got these two questions at the end:

Democrats were split on whether affordable housing developments should be forced to offer lots of parking spaces, Republicans largely understood that this requirement is dumb.

I am curious to see this question asked for general housing projects. I can see this changing the answer both ways. Presumably the original logic was ‘in order to be virtuous and affordable these projects need to offer less parking’ but the standard Democratic position could turn out to be the opposite, ‘you will not cheat the poor people out of a parking space, but if rich people don’t want one I don’t care.’

Both groups strongly agreed that speeding up construction and giving local governments deadlines are good ideas. This is a great idea and also a greatly popular idea, so it should be a relatively easy sell.

Alex comments on the last post, not bad but Patrick is still champion for now:

Alex: I think I can do one better than patio11’s “Save Our Parking” campaign. In my city of Virginia Beach, there has been a (so far successful) organized effort to prevent construction on what is currently a boat trailer storage yard. It’s just as much of an eyesore as you would expect, and offers minimal utility to residents, but putting an apartment building there is apparently flatly unacceptable.

A wild NIMBY appears! It’s not very effective.

Allison Shertzer: Guys you will never believe what just happened. A neighbor here just cold-called to make sure I knew that they are *gasptrying to build apartments behind my house and asked that I come to a meeting to speak out against this. It was like my research came to life!

Since I have never encountered a real NIMBY in the wild, I just let her speak. Her points were that (1) her home is an important part of her wealth so she has to protect it, (2) rental units just enrich landlords and do nothing for renters.

When I told her I was renting this property for the year, her tone completely changed. She said, “Well, I guess you aren’t interested in what happens to the neighborhood then.”

I answered that actually I am interested, since I would like to live here long term, and decades of underbuilding in nice neighborhoods like this one have made it hard to find a home.

Then she said that I’m not the kind of renter she was talking about. That my “likely income” made me an acceptable sort, or something to that effect. But she reiterated that I wouldn’t attend the meeting since renters aren’t invested in anything.

But now I will attend the meeting. I have no idea how this person got my number, but she may regret calling all the neighbors to unite us against building something.

(I note here that we’re renting a church property temporarily, which she did not realize, and her assumption was that I was associated with the church and would still gladly go out and ensure the less fortunate cannot live anywhere near me. I was in awe).

I was very nice. I told her that I understand the desire to keep one’s home value as high as possible, but giving neighbors veto power over development has created a housing crisis for future generations and that I consider this one of the great social problems of our time.

She protested that she was only trying to protect her beautiful “green” neighborhood against greedy developers and renters who desire to live here but can’t afford to. I really just could not believe how close the stereotypes were to reality.

Anyway, the world is on fire but I had to share that my research came to life and called me out of the blue today. We are never going to have abundant, affordable housing until we can stop local “interests” from blocking everything.

Orange Owl: Lol. This reminds me of when my kid’s (public) school was getting overcrowded and some parents were chatting and said maybe one “solution” would be to limit attendance to homeowners!! One of the parents then said she was a renter. The others’ facial expressions were priceless.

Paper says that access to joint savings vehicles such as houses is a strong predictor of marriage rates. Variation in housing prices is shown to increase home ownership and encourage greater specialization.

Corrine Low: We show a series of policy changes eroded the relative contract strength of marriage compared to non-marital fertility. Without a strong contract, people couldn’t harvest as much value from marriage to make jointly optimal, but individually risky choices, such as specialization.

Prior to these reforms, if one partner invested more in children while the other worked more, there was a guarantee of income sharing. Once divorce became easier + more common, women had to protect their own income streams! Which meant marriage no longer offered as much value!

Who was still able to harvest the value of marriage? Those with access to collateral. Wealth–assets, houses, etc–would be divided at the time of divorce, guaranteeing some recompense to the lower earning partner. Homeowners have NOT seen the same erosion of marriage rates!

[thread continues]

The thesis is that marriage rates are declining because marriage no longer represents an assurance of physical security, so it does not enable specialization for having and raising children. Such a strategy can no longer be relied upon without a large bank of marital assets, people realize that, so they don’t see opportunity in getting married, the contract is not useful.

I would be careful about attributing too much to this particular mechanism. I do buy the more general argument, that marriage is declining because the contract no longer makes financial sense if it cannot be relied upon. Failure in the form of divorce can be devastating to both parties – the high earner can be put into virtual slavery indefinitely, the low earner left without means of support. Without true commitment the whole thing is bad design.

A straightforwardly correct argument that labor should strongly favor building more housing. If we don’t build more housing, then all the gains from moving to high productivity areas, all the higher wages you fight for, will get captured by landlords.

Instead, unions typically hold up housing bills if the bills don’t extract enough surplus and direct it to unions. If a bill allows more housing to be built, and thus there to be more construction jobs, while not requiring those jobs to be union or pay above-market price for labor, they will prefer that housing not be built, those job not exist and their housing costs remain high. Similarly, unions have opposed streamlining CEQA in California, because CEQA presented a leverage opportunity they could use in negotiations.

The good news is that in California some unions are coming around, as the above Vox article chronicles. As we’ve discussed a bit previously, it has been a struggle to get them to begrudgingly agree to things such as a rule that, if ‘prevailing wages’ are paid and workers treated well, and not enough officially ‘skilled and trained’ workers are available, other workers could also be hired.

David Huerta, the president of California SEIU State Council, said after surveying members on issues they’re dealing with, it became clear SEIU needed to stand up more on housing. “Regardless of if you’re a janitor or a nurse or a health care worker or a home care worker, everyone overwhelmingly said the number one issue was housing affordability,” he told Vox. “We have members sleeping in their cars, who have big families sleeping in one-bedrooms, who are traveling hours and hours to get to work because they can’t afford to live near their jobs.”

…

But in April a major twist happened: two more construction unions — the California Council of Laborers and the state Conference of Operating Engineers — broke with the Trades to publicly support Wiener’s housing bill. “We believe the balance that this legislation strikes will result in more available housing and ultimately lead to more affordable housing that could be utilized by our membership and those in need,” said the Operating Engineers in a public letter.

The problem is that the incentives for unions are beyond terrible. They are there to protect the exact existing jobs of the exact existing members, and help them extract as much as possible. Offering to grow the union, and create more good union jobs? They might actively oppose you.

One important factor shaping the politics in California is that not all labor groups see rapid membership growth as inherently positive.

Laura Foote, executive director of YIMBY Action, recalls one of her earliest memories of advocating to expand California’s housing supply. “I was just starting to map out who would be pro-housing, and anyone who built housing seemed like a natural ally,” she told Vox. Foote met with a San Francisco planning commissioner who was also a member of the electrical trades.

“I had a one-on-one with him like, ‘Okay, all the construction industry trades are going to be on board? Let’s build a lot of housing!’ And he was very blunt that no we do not want to unleash production … For him, there was a problem that if we unleashed housing production and grew our labor force, then when there’s a downturn all of his guys would be banging down the door at the union hall when times are low and out of work.”

They don’t want to allow more jobs, because if those jobs are union they might later be lost or existing members threatened, and if they are not union then they’re not union.

How much does the ‘prevailing wage’ requirement cost? No one knows for sure.

No one could say exactly how much more a project might cost if prevailing wage is required, and different estimates abound. Ben Metcalf, the managing director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, told Vox his organization believes it increases prices in the 10-20 percent range, but can vary a lot by region. Some estimates have it lower than that, and some others have it higher.

The snappy answer is that if the ‘prevailing wage’ was indeed the prevailing wage, paying it is what you would do anyway. Which tells us this means something else, and a 10%-20% total increase in costs implies it is quite a bit higher indeed, and you don’t get much in the way of higher quality in return.

That still seems highly affordable given how things are going these days, if it alone lets you build. The problem is that if others also come for large shares of the pie, for too many others, it can add up fast.

New York Times cites what they say is a trend of landlords boasting about being horrible to tenants. Alex Tabarrok noes that one of their examples of dirty deeds is this landlord who evicted a tenant and will be confiscating their security deposit, because the tenant literally took a sledgehammer to the place.

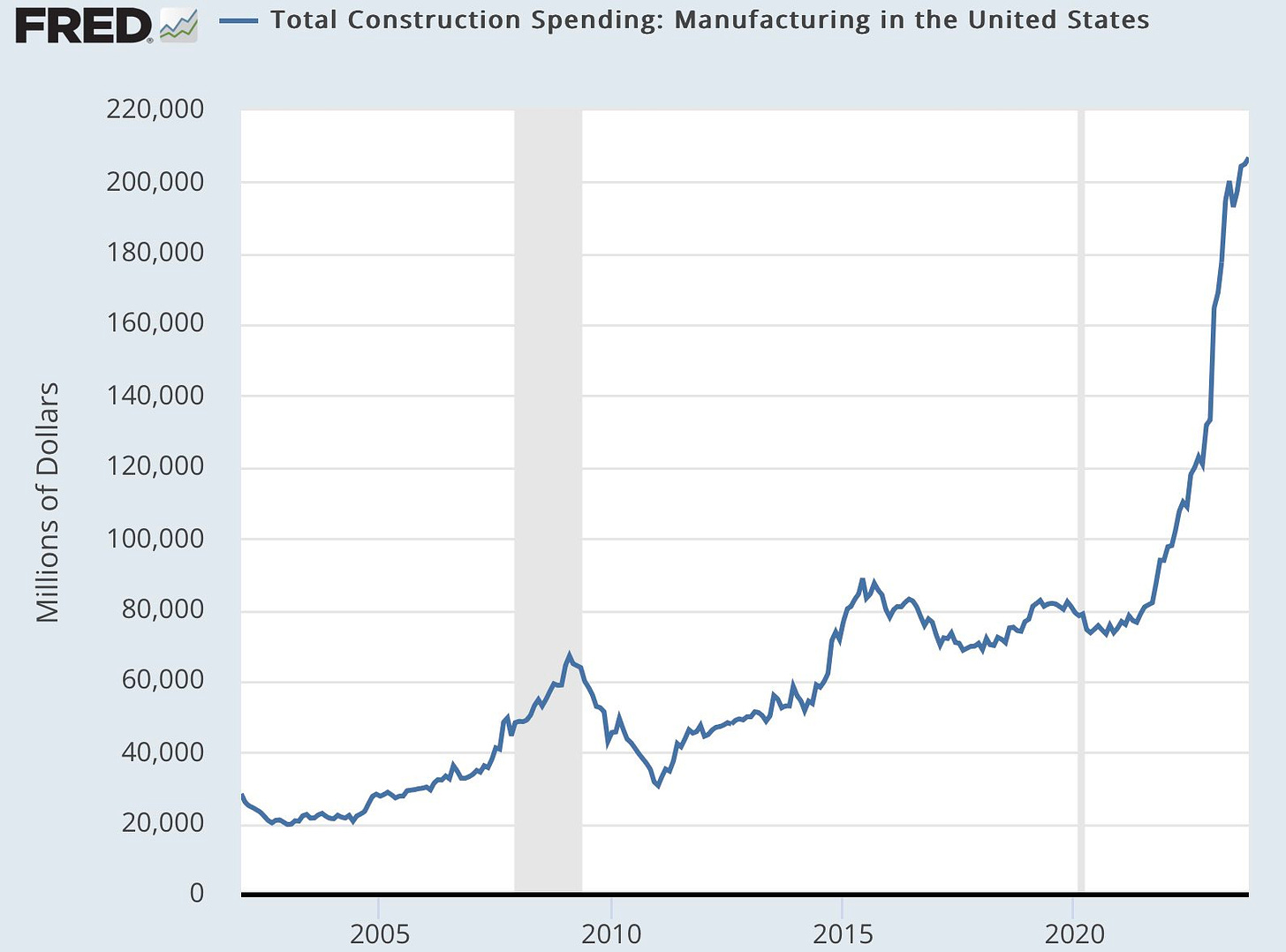

Isaac Hasson: This tweet is brought to you by the most beautiful chart you’ve ever seen

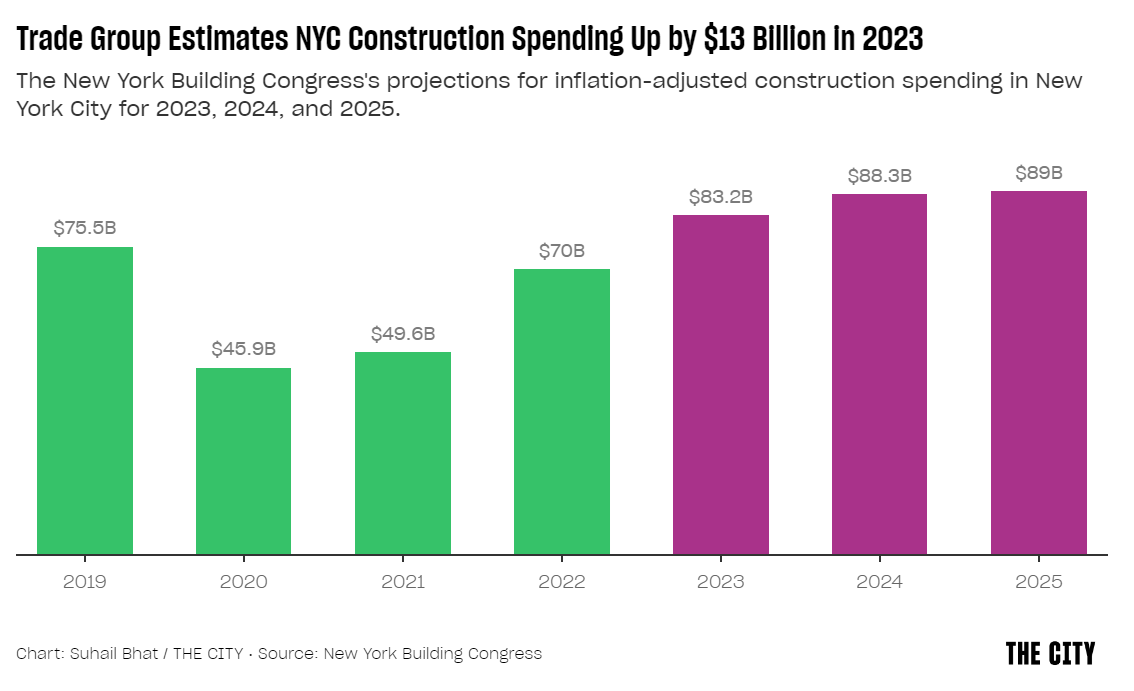

If we are spending that money well this is fantastic, and note that the bottom of the chart is indeed the zero point. Are we spending the money well? In the places and for the things we want, and efficiently?

Airbnb offers us a housing council, convening various government officials and experts, to ensure that their offerings ‘make communities stronger.’ As far as I can tell, this is them supporting a few unrelated generic good-vibes housing-adjacent things.

Matjaz Leonardis: If you read this story and it enrages you, you are The Batman. If instead it makes you try to come up with clever ways of showing to everyone that they too would let someone freeze to death in the name of upholding a contrived standard, then you are The Joker.

Cranky Federalist: I am going to become the Joker.

Story (no citation was offered): Outrage spread Friday after the story about a pastor in Ohio who was arrested and charged for opening his church to homeless people when extreme cold weather struck his town gained national attention.

Chris Avell, the pastor of an evangelical church called Dad’s Place in Bryan, Ohio, pleaded not guilty last Thursday to charges that he broke 18 restrictions in zoning code when he gave shelter to people who might otherwise have frozen to death.

Avell garnered the attention of the Bryan City Zoning Commission last winter, when he invited unhoused people to stay in his church to avoid the cold and snow.

In November, officials told him Dad’s Place could no longer house the homeless because it lacks bedrooms. The building is zoned as a central business, and Ohio law prohibits residential use, including sleeping and eating, in first-floor buildings within business districts.

Zvi: Who are you if you think ‘aha an excellent illustration to help convince people to loosen their zoning laws’?

Andrew Retteck: Commissioner Gordon.

Matjaz Leonardis: It’s interesting to struggle with finding a character because this highlights how irrelevant “the people” are in that story.

White House proposes $10 billion in ‘down payment assistance’ for first-time homebuyers. So I guess we are tapping the sign, then?

Austin keeps building gorgeous new office buildings, often giant skyscrapers, despite little demand by anyone for new offices to work in, and few tenants lined up. People worry about a bust, older less cool office space is losing value.

I would not worry. Austin’s real estate prices have gone through the roof in the last few years. Yes, they are running ‘Field of Dreams’ here, but that should be fine. If the price comes down a bit? Good. High rents are not a benefit. High rents are a cost. I do not much care if some real estate developers lose money. If it turns out Austin ends up with too much commercial space versus not enough residential space to support it, the solution is to build more residential space.

Tyler Cowen calls for NIMBY for commercial real estate, predicts strong gains from resulting mixed use neighborhoods. As he points out, if commercial real estate was cheaper and more plentiful, and I would add more convenient, more people would use it rather than working from home. He is more gung-ho on this than I am, seeing in-person interactions as more valuable than one’s freedom to not have those interactions, but certainly the option would be appreciated.

When I think about Tyler’s example of adding a bunch of commercial towers to the Upper East and Upper West Sides of Manhattan, that does not seem obviously good to me. I think it would be good to have a bunch of commercial midrange stuff there, but that going pure vertical (e.g. 30+ stories) in those areas would be a tactical error, destroying vibes people value. Central Park makes it difficult to pull off well. As usual (see discussions of congestion pricing), Tyler Cowen does much not care if inhabitants of Manhattan are happy.

It is on. San Francisco refuses to build, and the state of California is having none of it.

Sam D’Amico: The state has figured out specifics of why SF doesn’t build any housing and has fixes SF will be compelled to implement. Meanwhile it’s highly likely SF’s board of supervisors (who are … notionally, members of the exact same political party) are going to try to block it.

Chris Elmendorf offers a thread: When SF adopted its new housing element in Jan. 2023, it committed ex ante (behind the veil) to adopting any “priority recommendations” from the audit.

Today’s report reiterates this commitment in bold font and then leverages it, listing 18 “Required Actions” that the city must undertake on pain of having its housing element decertified (exposing city to Builder’s Remedy).

Each “Required Action” comes with a deadline. Some arrive in just 30 days!

SF’s Board of Supes has spent last 6 months hemming, hawing, watering down & wavering on @LondonBreed’s draft constraints-removal ordinance.

California says: pass it in 30 days, or else.

Here’s the money finding from the audit: – SB 35 projects (ministerial under state law) go fast – everything else get stuck in the city’s molasses – ergo, all housing development permits in SF should be ministerial

Getting there will not be easy, politically. Some tells: – HCD invited the current supes, planning commissioners & historic preservation commissioners to meet about the audit. Most declined. – City’s own planners (!) told HCD they operate in shadow of a lawless Bd of Supes.

And while there are many strong “Required Actions” in the report, there’s also significant ambiguity on the central question of what class(es) of housing projects must be made ministerial.

The report says that by Jan 2024, a small class must be ministerial. And by fall of 2026, city must establish “a local non-discretionary entitlement pathway, w/ progress updates to HCD every 6 months.” A pathway for what? For *allcode-compliant housing projects? Or just for projects that are ministerial per specific state laws? (SB 423 will require certain projects to be ministerial starting mid-2024. Housing Element Law will require certain other projects to be ministerial starting in 2026. But what about the rest?)

[thread continues]

Annie Fryman: Surprise! By next summer, most housing developments (including market-rate) in SF get streamlined, objective approvals through a last minute update to @Scott_Wiener’s SB 35 — now known as SB 423. No CEQA, discretionary review, appeals… my piece.

Sam D’Amico: SB 423 is now law … SF NIMBYs are now (specifically) de-powered.

Who will win the fight?

Benjamin Schneider says that the old San Francisco regime has come to an end, and looks at its potential futures. He attempts to be even-handed as possible, which is difficult under the circumstances, emphasizing with concerns about ‘displacement’ and gentrification. So we get things like this:

Benjamin Schneider: What happens to a San Francisco neighborhood when development is allowed? Ironically, we have the answer because of the most notorious NIMBY incident in recent San Francisco history. In 2021, the Board of Supervisors delayed a 495-unit development on Stevenson St. in SoMa, on the legally dubious grounds that the parking-lot replacing project failed to analyze its gentrification impacts.

A year later, the new environmental impact report was released. It found — wait for it — that the development would not cause displacement because it was to be constructed on a parking lot. In fact, the analysis determined that leaving the site as a parking lot would be more likely to cause displacement than developing it with nearly 500 homes, including 73 deed-restricted affordable homes.

Overall, he is optimistic that the new regime is a vast improvement.

Unleashing lots of housing construction does not automatically increase racial or economic diversity. In plenty of cases, it has done the opposite. But what San Francisco has going for it, and what it continues to have going for it even under its new housing policy regime, are strong tenant rights and strict regulations governing the demolition of existing housing. State laws like AB 2011 direct development toward under-utilized commercial areas. Other local and state policies require homes slated for redevelopment to have been previously occupied by the owner, not a tenant. In theory, this should mean that the person whose home is being redeveloped is voluntarily cashing out, not involuntarily being pushed out.

Is this a perfect system for development without displacement, for improving affordability, or for creating a green, transit-oriented metropolis? Probably not. But is it an orders of magnitude improvement on the previous housing policy regime? Absolutely.

Claim from a Berkeley newspaper that Berkeley is recovering unusually well thanks largely to a boom in housing construction, also with its relative dependance on UC Berkeley rather than offices, with downtown doubling in population and expected to double once more within five years.

Meanwhile in Palo Alto, new builder’s remedy project aims to build 3x taller, 7x denser than city zoning code allowed, with a 17 story tower. Comments complain about there not being enough parking, because everything is maximally cliche.

Mayor Eric Adams is trying for a lot of the right things, the usual list of incremental improvements.

Alas, those central planning instincts never go away. A council member effectively vetoes and ends a Crown Heights project that would have given the local community everything it asked for, while building on a vacant lot, because the Adams administration plans to do a ‘larger rezoning’ and they should wait for that. Wait, what? Under the new plan, the building would be permitted, so why not allow it now?

The key is not to build housing. It is to let people build housing.

Greg David: NYC Will Build Just 11,000 Homes This Year, Half of 2022 Total, Annual Report Finds. The forecast by the New York Building Congress reflects the fallout from the expiration of a major tax break for developers.

But the key issue in the report is the decline in residential construction, driven by the expiration of the 421-a tax break.

First implemented in the 1970s to spur affordable housing construction, 421-a eliminated or reduced property taxes for up to 35 years for developers of rental buildings. Those breaks currently cost the city $1.8 billion a year in lost tax revenue. Developers receiving the benefit in recent years were required to set aside 25% or 35% of their housing units as income-restricted affordable apartments.

Research by the Furman Center had suggested that developers in 2022, anticipating a lapse in the 421-a program, applied for permits to build 70,000 units — enough to produce 20,000 new homes a year for three years. A year ago, the Building Congress expected a similar result, forecasting 30,000 completed units for 2023.

However, to qualify for the tax break, builders had to both put foundations in the ground by June 2022 and be able to complete construction by 2026. The data from the Building Congress and the Real Estate Board suggest that relatively few projects are moving ahead under those conditions.

I agree that the incentive is worthwhile, but this looks a lot less like ‘there was a real decline in housing construction’ and more like ‘everyone moved their actions in time to quality for a major expiring tax break.’ The question is what happens after 2026, once all that construction finishes.

New York City offers pilot program, paying homeowners up to $395k to build ADUs. This is of course insane. If you want more housing, legalize housing. There’s no shortage of demand if people were allowed to build it.

From 2021 ICYMI: Did you know that if you offer tax breaks for ‘low-income’ housing, but purchases still require large down payments, you are effectively subsidizing the children of the rich who borrow the money from their parents? Bloomberg investigated the related program in NYC, and that’s exactly what is happening.

Top ten skyscrapers of 2023, three of them are from NYC.

Getting rid of parking minimums seems pretty great.

Joshua Fechter: Breaking: Austin just became the largest U.S. city to get rid of minimum parking requirements for new developments Nixing those requirements will allow more housing units amid the city’s affordability crisis, encourage density & discourage car-dependency, supporters say.

Other cities are also getting rid of off-street parking minimums, including San Jose, Gainesville and Anchorage. New York City is exploring it too, in the place where a parking requirement makes absolutely no sense.

Austin also tried letting developers build taller in exchange for more affordable housing. It turns out that they technically violated Texas state law and ‘the interests and legal rights of Austin homeowners’ according to the villainous Judge Jessica Mangrum.

Audrey McGlinchy (Kut News): Judge Jessica Mangrum said the city failed to adequately notify property owners that developers could build more than what is typically allowed near them. As a result, the city has to throw out the policies, although they will not be fined despite the plaintiffs’ request. A fourth housing policy adopted in 2019, which lets developers bypass certain building rules as long as half of what they build is for people earning low incomes, was upheld by the court.

A notification problem, you say? Annoying, but ultimately no problem. Let’s put everyone on proper notice.

Except it seems they tried that, and shenanigans?

In the ruling signed Friday, Judge Mangrum said the city again failed to send proper notice to nearby homeowners. The city did mail homeowners to notify them about one of the housing programs, but the plaintiffs’ lawyer argued not all homeowners within a required distance received the notice and that the language of the mailer was not sufficient.

“I’d really like to see the city start following the rule of law. It’s not that difficult,” Allan McMurtry, who owns a home in Austin’s Allandale neighborhood and is one of the plaintiffs, told KUT.

Allan McMurtry is, of course, lying. He wants Austin to continue to technically fail to follow the convoluted notification rules so that he can keep suing to block development.

Still, there is lots of good progress:

Becker said he is looking into additional legal action against more recent zoning changes made by the City Council. Last week, council members voted to let people build up to three homes on land where historically only one or two homes have been allowed.

Kentucky House Bill 102 attempts to do it all. What a list:

Steven Doan: A great thread on House Bill 102 I sponsored. Having served on the board of directors for a local homeless shelter, I felt the need to do more to address housing insecurity in our state. I look forward to addressing this issue for the people of Kentucky.

Nolan Gray: Wow. Kentucky State Representative Steven Doan that would implement…basically the entire YIMBY program! I’m still learning details, but this is a great model for a zoning reform omnibus bill.

Right off the bat, Section 3 forbids jurisdictions from arbitrarily mandating larger homes and apartments, which effectively place a price floor on housing. Jurisdictions must default to the building code, which is rooted in actual health and safety considerations.

Section 4 likewise preempts various design/architectural/amenity mandates (e.g. forcing the construction garages) that raise housing costs without any basis in health of safety. These can often quite onerous in exclusionary suburbs. Let homebuyers make these tradeoffs!

Arkansas passed a law doing something similar in 2019, banning arbitrary minimum home sizes and other design/architecture/amenity mandates. In Arkansas as in Kentucky, it was really a handful of exclusionary jurisdictions exploiting these rules.

Section 5 just goes there and legalizes fourplexes in residential districts statewide. Cities can’t be demolitions, but they can maintain current massing rules. Extra floor area will be needed to get units here, but an important (and symbolically valuable) step.

Section 6 legalizes ADUs, and preempts most of the usual poison pills, e.g. owner-occupancy mandates and prohibitions on renters. It also clarifies that mobile homes cannot be banned, and imposes a 30-day shot clock. Very nice.

Section 7 does something new: it legalizes manufactured tiny homes in all residential districts.

Section 8, AKA the unsexy process reform section that would matter a lot: establishes a 60-day shot clock for all residential permits, caps fees, and limits hearings/studies—all quiet sources of slowing housing production that benefit no one. Love it.

Section 9 extends all of the same protections to variance requests—again, very cool. The delays and costs associated with variances can fall hardest on lower-income families who may own non-conforming properties. No reason not to set clear standards here.

Section 10 ends minimum parking requirements within a half mile of all transit stops, statewide. Simple, but potentially transformative.

Section 11 legalizes home-based businesses statewide. Again, regulations here can’t just be arbitrarily invasive—they must be rooted in nuisances. Key for expanding entrepreneurship opportunities.

Section 12 allows residential uses in commercial areas. Potentially hugely impactful as we figure what to do with all of these half-empty strip malls and office parks. Corridor midrise has been a major source of new housing in reforming jurisdictions.

Lucky Section 13 ends prohibitions on rentals, and forbids occupancy limits tethered from health-safety codes. Jurisdictions regularly place arbitrary limits on the number of unrelated people who can live together. (Often using antiquated language about “blood,” etc.) Done!

Section 14 reinforces an enduring theme of the bill, which is that zoning ordinances adopted pursuant must be rooted in actual health and safety considerations—no arbitrary or exclusionary nonsense.

Section 15 clarifies the legal standards on which challenges to the law must be considered. Crucial as NIMBYs in e.g. Montana try to torpedo pro-housing reforms through the courts. Where there’s ambiguity, default to liberalization.

Section 17 requires cities to update their zoning ordinances in compliance with this section. Wonky, but so crucial. We haven’t done this in recent bills in California and it has come back to bite us. Cities need to change laws and update processes. Sections 17 and 18 clarify powers reserved by HOAs and cities. I know many of you won’t like Section 17, but in my experience, it can be a valuable compromise for passing bigger pro-housing reforms.

Tokyo keeps growing and allows lots of freedom to build while keeping prices low. Tyler Cowen proposes that instead those low prices in Tokyo are instead due to the NIBMY culture that is Japan. If you have no immigration and in general can’t do anything all that productive, but allow instead only low-value construction, you perhaps get low housing prices. The ‘true YIMBY’ would instead increase prices, because it would provide more value, and Japan remains poor relative to us instead. I see the point, but also consider this redefinition (reframing? reconstruction?) too clever by about half.

Excellent progress being made.

Kenneth Chan: Transit-oriented housing development will be the law of the land in Metro Vancouver, across BC. Overriding cities: – #SkyTrain stations: Minimum 20 storeys within 200 metres; 8-12 storeys, 201-800m – Density for bus loops

For transit-oriented density near bus exchanges, the BC government will require Metro Vancouver cities to allow the following: – 12 storeys within 200 metres of bus exchange, with 4.0 FAR – 8 storeys and 3.0 FAR, 201-400 metres.

As part of British Columbia’s new transit-oriented development legislation, minimum vehicle parking requirements for new buildings will be eliminated within 800 metres of a #SkyTrain station and 400 metres of a bus exchange.

Alex Bozikovic: It’s extraordinary what BC’s government has done: changing zoning to allow apartments in big swaths of each city, including Vancouver. Following California’s lead to make the changes that city governments have been fighting hard against.

Hunter: Wow…. you’re telling me that builidng housing…. keeps housing prices lower? Who could have seen this coming. This is such a twist.

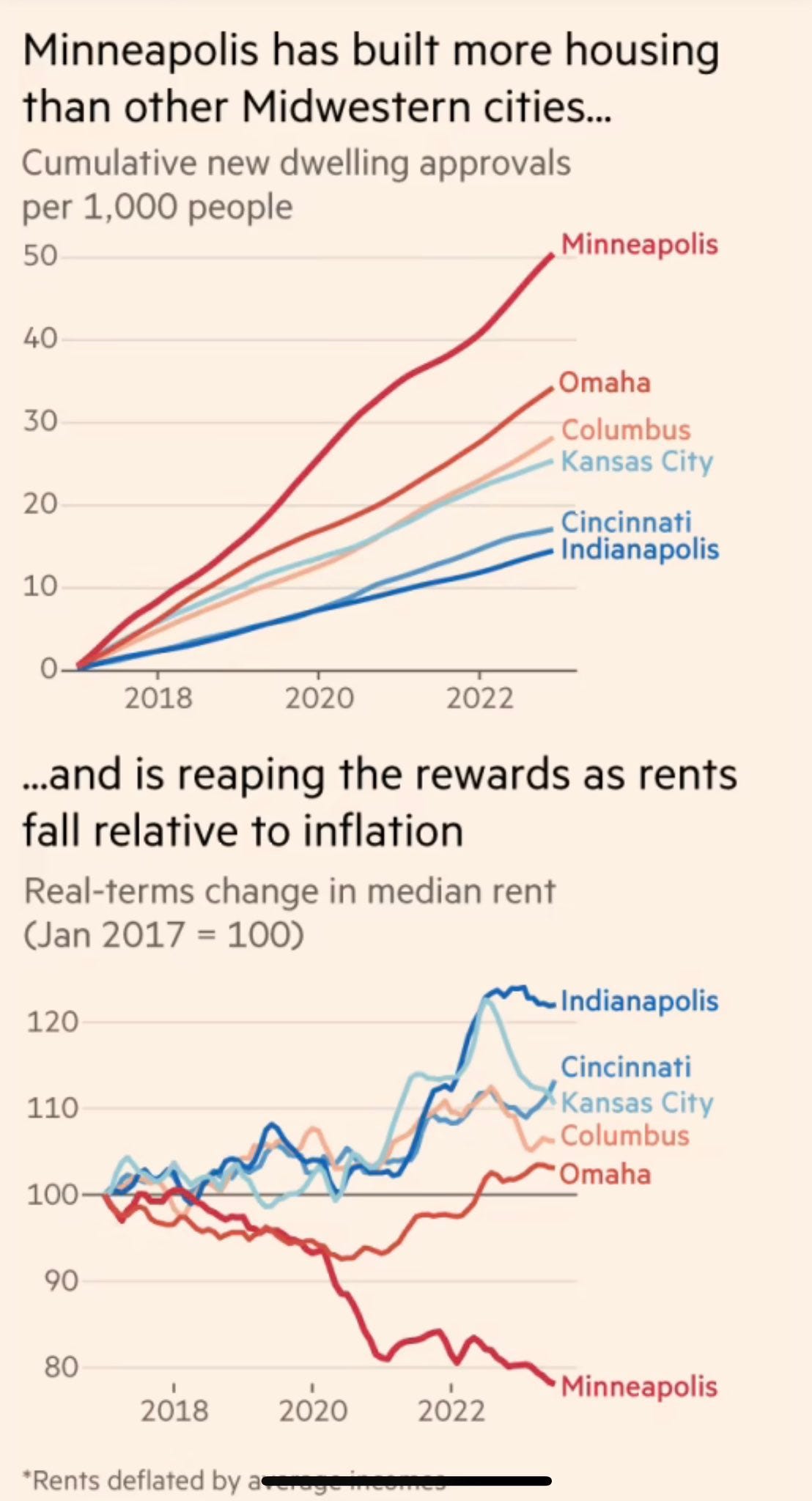

That is not a small effect. Minneapolis has seen a dramatic drop in rents. For the five cities chosen, the more construction, the better the change in rents, although I presume they are somewhat cherry picked for that.

Presumably this involved a lot of good luck. The impact should not be this big from only ~25 new units per 1,000 people, although tipping points are possible. One could look at the timing and propose this has something to do with the riots of 2020, as well, although even excluding that drop we still have a big improvement.

As usual, we have the effect size dilemma.

-

Effect is big? Must not be causal, you can ignore it.

-

Effect is not big? Could be random, not big enough to care, you can ignore it.

Minneapolis is still one of a small group of pro-housing cities, successfully built more housing, and saw its rents drop dramatically.

Minnesota in general is looking to supersede residential zoning rules across the state.

They are building lots of housing, and it turns out that brings down the price, who knew.

Ryan Briggs: lord, I’ve seen what you’ve done for others.

Ryan Moulton: It is embarrassing how California gets lapped by Texas at all the things California wants most just by letting people do things. (building housing and renewable energy.)

Headline from Bisnow: Texas Apartment Markets Could Take A Financial Hit As Oversupply Fuels Rent Declines

Pricing power across apartment markets in Texas has slipped just as thousands of new units are coming online, sparking concerns that conditions are ripe for an onslaught of distress.

Yes. It is that easy. Let’s do it.

It looks like Ron DeSantis is a fan of legalizing housing at the state level, continuing his major push.

An update to last year’s monumental Live Local Act to boost affordable housing is on its way to the House after clearing the Legislature’s upper chamber by a unanimous vote.

The measure (SB 328) includes new preemptions on local development controls and clearer details for how some projects should rise. It also includes special considerations for Florida’s southernmost county and a late-added exemption for short-term vacation rentals.

…

The original law, which Gov. Ron DeSantis signed last March, attracted national headlines for its boldness and implications.

It forces local governments to approve multifamily housing developments in areas zoned for commercial, industrial and mixed uses if the project sets aside 40% of its units at affordable rates, defined as offering rents within 30% of the local median income. The developments, in turn, would be required to adhere to a city or county’s comprehensive plan, except for density and height restrictions.

[and other things]

…

SB 328 would “enhance” the existing law, Calatayud said, and further address “quality of life issues” for Florida residents.

If passed, the bill would:

— Prohibit local governments from restricting a development’s floor area ratio (the measure of a structure’s floor area compared to the size of the parcel it’s built upon) below 150% of the highest allowed under current zoning.

— Enable local governments to restrict the height of a proposed development to three stories or 150% of the height of an adjacent structure, whichever is taller, if the project is abutted on two or more sides by existing buildings.

— Clarifies that the Live Local Act’s allowances and preemptions do not apply to proposed developments within a quarter-mile of a military installation or in certain areas near airports.

— Requires each county to maintain on its website a list of its policy procedures and expectations for administrative approval of Live Local Act-eligible projects.

— Requires a county to reduce parking requirements by at least 20% for proposed developments located within a half-mile of a transportation hub and 600 feet of other available parking. A county must eliminate all parking requirements for proposed mixed-use residential developments within areas it recognizes as transit-oriented.

— Clarifies that only the units set aside for workforce and affordable housing in a qualifying development must be rentals.

— Requires 10 units rather than 70 to be set aside for affordable and workforce housing in Florida Keys developments seeking the “missing middle” tax exemption.

— Makes an additional on-time earmark of $100 million for the Hometown Heroes Program.

Turns out there are many such cases.

Faith Alford: ‘Year of the renter’: Rent in Charlotte beginning to fall as more housing available.

Rent.com said that in December, median rent was $1,839. That is more than a seven percent drop since the July peak.

Anna: Apartment in Atlanta, rent is down 12% in 2 years and 18%! off last year’s asking rent. I suspect demand may also be down due to high rents driving some renters out of the market (combining households).

The corporate landlords with their price sharing did it to themselves.

Business Insider: Rents in Oakland have fallen faster than anywhere else in the US for a simple reason: The city built more housing.

Matt Baran Architect: It seems like it shouldn’t be that hard to figure out

Oakland presumably also has other unique factors, like issues with rising legalized crime and the previous stratospheric level of rent in the Bay area.

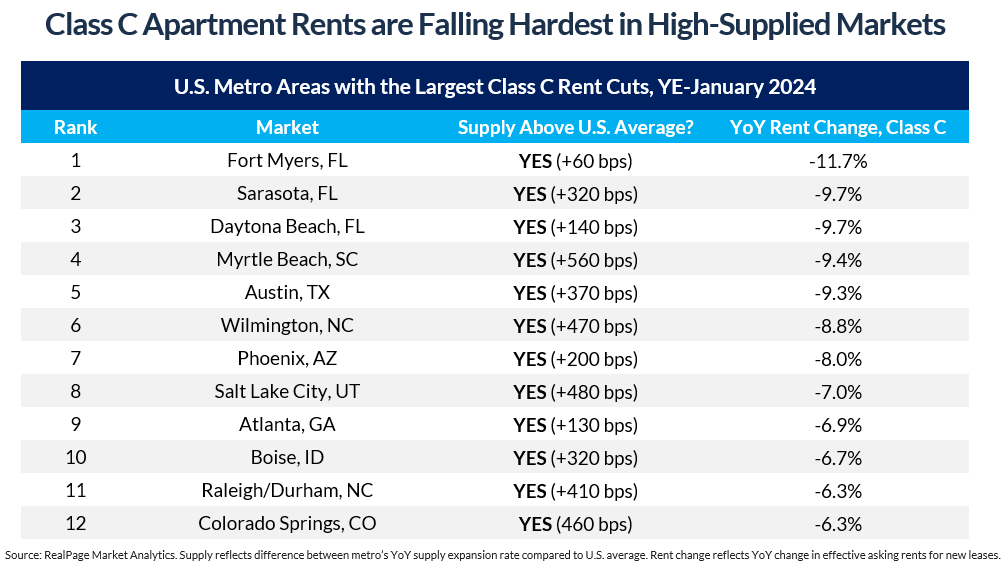

Jay Parsons: When you build “luxury” new apartments in big numbers, the influx of supply puts downward pressure on rents at all price points — even in the lowest-priced Class C rentals. Here’s evidence of that happening right now:

There are 12 U.S. markets where Class C rents are falling at least 6% YoY. What is the common denominator? You guessed it: Supply. All 12 have supply expansion rates ABOVE the U.S. average.

There’s no demand issue in any of these 12 markets. They’re all among the absorption leaders nationally — places like Austin, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Atlanta and Raleigh/Durham, Boise, etc. But they all have a lot of new supply.

Simply put: Supply is doing what it’s supposed to do when we build A LOT of apartments. It’s a process academics call “filtering.” New pricey apartments are pulling up higher-income renters out of moderately priced Class B units, which in turn cut rents to lure Class C renters, and on down the line it goes.

Less anyone still in doubt, here’s another factoid: Where are Class C rents growing most? You guessed it (I hope!) — in markets with little new supply. Class C rent growth topped 5% in 18 of the nation’s 150 largest metro areas, and nearly all of them have limited new apartment supply.

Most new construction tends to be Class A “luxury” because that’s what pencils out due to high cost of everything from land to labor to materials to impact fees to insurance to taxes, etc. So critics will say: “We don’t need more luxury apartments!” Yes, you do. Because when you build “luxury” apartments at scale, you will put downward pressure on rents at all price points. Spread the word.

M. Nolan Gray: The cool thing about “luxury” housing is that, if you just keep building it, it becomes affordable.

If you want to build 100% affordable housing at zero cost to taxpayers, Los Angeles potentially shows you the way with this one weird trick.

The weird trick is that you offer, in exchange for the housing being 100% affordable, to otherwise get out of the way.

As in, you use Executive Directive 1, with a 60-day shot clock on approvals, based only on a set of basic criteria, no impact studies or community meetings or anything like that, you pay prevailing wages as in what people will agree to work for instead of “prevailing wages,” and are allowed to use the 100% affordable rule to greatly exceed local zoning laws.

And presto, 16,150 units applied for since December 2022, more than the total in 2020-2022 combined, with 75% having no subsidies at all. Or rather, the subsidies took forms other than money. That makes them a lot cheaper.

One catch is that ‘affordable’ here means cheaper than market, but not that cheap.

Ben Christopher (Cal Matters): To qualify as a 100% affordable housing project under the city of Los Angeles’ streamlined treatment, a studio can go for roughly $1,800. Compare that to a traditional publicly subsidized project which could charge as little at $650 for the same unit.

And you can bet this studio doesn’t have a parking spot.

…

The bet is that housing costs are so astronomically out of reach in Los Angeles that even someone making north of $70,000 per year would jump at the chance to rent “a more bare bones product without all the bells and whistles” for what could amount to a modest rent reduction.

…

“This is just a whole new product specifically catering to the middle-lower end of the market. That just wasn’t a thing that people were doing before,” said Benjamin.

It is a very good bet. There is tons of pent-up demand for bare bones apartments, because we don’t let people build bare bones apartments. With a modest discount many will be all over it.

Note that none of these projects have actually been built yet. As you would expect, lawsuits are pending. So we should not celebrate yet. There are also lawsuits over the city’s attempt to walk back approvals for a handful of projects in single-family areas, where the order has now unfotunately been walked back.

If nothing else, this one reform clearly worked. Previous regulations prevented evictions, effectively letting tenants steal the apartment they rented, so land owners were keeping properties off the market. The premium being charged was large.

Reagan Republican: With Milei’s decree deregulating the housing market, the supply of rental units in Buenos Aires has doubled – with prices falling by 20%.

Austen: So many Twitter accounts have argued the opposite of this would happen for so long.

Alexandria, Virginia ends single-family-only zoning.

Washington State considering bill to cap rent hikes at 7% annually. When a tenant leaves, the new rent could still be raised more. Any form of rent control is a deeply destructive idea, but this is a lot less damaging than most, as vacant apartments reset and 7% should be sufficient over time. If this was indexed to inflation to guard against that failure mode (e.g. set at 7% of CPI+4% whichever is larger) and was clearly going to stick at that level then I would actually be largely fine with it as a compromise in the places in danger of implementing rent control more harshly, especially if this then allows for building more housing, purely to head off more destructive versions. There is a big difference between 7% and New York City’s historical much smaller allowed increments.

I do think that landlords will sometimes seek to ‘hold up’ the current tenant and extract the benefits of not having to move, and that this can be destructive. I don’t think this is important enough to risk installing such a regime, that goes very dangerous places, but the real danger is when you cannot keep pace over time, and 7% should mostly solve that.

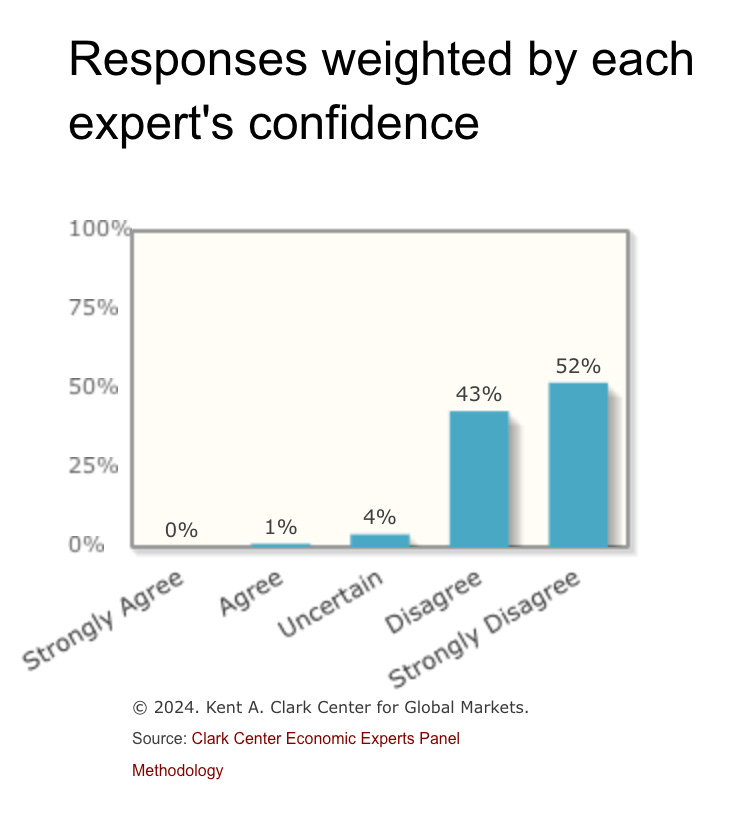

Jay Parsons covers the trend of implementing such laws, or rather covers the coverage. Major outlets like The New York Times cover such efforts, and almost never point out that economists universally agree such laws are terrible, crippling supply and increasing overall prices.

This is, as he points out, like covering climate change denialists and not pointing out that scientists agree that climate change is real. It is that level of established as true. You should treat rent control supporters the way you treat climate change denialists.

Jay Parsons: Here’s what the science says: 1) A survey of 464 economists found that 93% agreed that “a ceiling on rents reduces the quantity and quality of housing available.” (AER)

2) A Stanford study found that rent control in San Francisco reduced rental supply, led to higher rents on future renters, created gentrification, and reduced housing options for all but the most wealthy people. (Diamond)

3) Numerous studies have shown that rent control incentivizes higher-income earners to stay put, reducing availability for lower-income earners. One famous one was former New York Mayor Ed Koch, who maintained a $475/month rent controlled apartment even while living in the mayoral mansion. This leads to a misallocation of housing resources. (Olsen, Gyourko and Linneman).

4) Rent control can “lead to the decay of housing stock” due to lack of funds to maintain rentals. (Downs, Sims).

5) An MIT study found that when rent controls were REMOVED from Cambridge MA in the 1990s, rental housing quality improved as maintenance got funded, crime was reduced, and nearby property values improved. (Autor, Palmer, and Pathak)

6) Rent control reduces supply. When St. Paul, MN, adopted rent control, multifamily building permits plunged 47% in St. Paul while rising 11% in nearby Minneapolis and rising in most of the U.S., too. (U.S. HUD data) 7) Studies show that “upper-income renters gained more than lower-income renters” from rent control. (Ahern & Giacoletti)

…

Critics will claim there’s science favoring rent control, too, but that’s misleading. For one, even anti-vaxxers stake claim to research to support their views… but that doesn’t mean that the research is of equal weight or as widely supported by scientists as pro-vaccine research.

Aziz Sunderji: Agree! 95% of top flight economists surveyed by U. Chicago disagreed that “local ordinances that limit rent increases for some rental housing units…have had a positive impact over the past three decades on the amount and quality of broadly affordable rental housing…”

In a highly amusing synthesis of housing and transit policy issues, Matt Yglesias proposes YIMBY for cars. Building more houses makes traffic worse, but the way it does that is that people buy and use cars, so what if we put up huge barriers to cars instead of putting up huge barriers to housing? Congestion pricing talk so far is a good start, but what if we really dropped the hammer.

The stated goal is to have the high speed rail line working at 200 miles per hour between Los Angeles and Las Vegas in time for the 2028 Olympics. The train should be faster than driving, but analysis suggests from many places in LA it will still be slower than flying. Flying has high fixed costs due to security and timing issues, but the hour it will take to reach the train station from downtown LA is a problem.

The hope is that once you have one line, getting more lines becomes far more attractive and feels more real. It is very American to start its high speed rail with a line that gives up on getting the right to go to actual central LA and then connects it to Vegas. I suppose one must start somewhere.

Ben Southwood points out that when people say that additional roads or lanes induce demand, mostly this is not the case. Instead, what is happening is that demand to drive often greatly exceeds supply of roads. Expanding the road creates a lot of value by allowing more driving, but due to the way the curves slope speed of travel changes little. That does not mean demand rose or was induced. Over longer periods of time, yes, this then creates expectations and plans for driving.

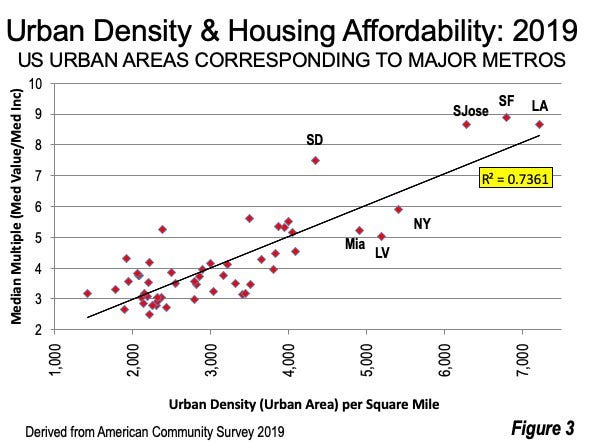

Emmett Shear argues: Objectively, density is dramatically undersupplied. You can tell, because dense housing is more expensive than less dense housing by a lot. We should legalize increasing high-demand density.

Which is indeed the correct way to think about Scott Alexander’s argument that increasing density through more building would increase prices. Perhaps it is true, but if true that is because it enhances value even more, which means we should totally do that. Emmett has various old threads on this. Various causation stories still need to be considered and reconciled, since density follows from desirability to a large extent.

How big a tax would you pay, as a real estate developer, to get up-zoning? Seattle ran that experiment, results say that they charged far too high a price. I find the paper’s term ‘strings attached’ a strange way of describing extortion of money (or mandatory ‘affordable housing’), but in the end I guess it counts.

Note that they greatly underestimated the cost of providing this ‘affordable’ housing:

However, in the first year that MHA was in full swing, an overwhelming majority of developers (98%) chose the payment option. This suggests either that the performance option constitutes a large “affordability tax” on the developers or the payment option levels were set too low.

A simple and obvious solution is to auction off the up-zoning rights. As in, for each neighborhood, decide to allow construction of some fixed number of additional buildings, within new broader limits. Then for each building, auction off the permit to the highest bidder, and then pretend (reminder: money is fungible) to use that money to support affordable housing, or distribute the profits to local residents in some way, or something similar. And of course, if the local residents want to prevent construction so badly, they can buy the permit and not use it.

Beyond Speed: Five Key Lessons Learned From High-Speed Rail Projects.

-

People Focus. You need bipartisan long term support and community engagement, including reaching out via social media etc.

-

Means to an End. Capacity, connectivity, carbon. OK I guess, sure.

-

System Integration is Vital. Yes, you also need stations and tunnels, who knew.

-

HSR as Environmental Opportunity. Hold that everything bagel for a second.

-

Leadership in Megaprojects. Realistic projections, risk communication, don’t shoot the messenger, ‘own the whole’ and be curious about opposition. OK.

A lot of generic ‘do all the good management things’ and ‘get buy-in from actual everyone.’ Most projects would never happen if they required such standards, but at least they are things one could reasonably aspire to. And then there’s that fourth one…

HSR projects can be described as environmental projects with a railway running through them and this is often a helpful perspective to adopt. Seeking to deliver a positive environmental legacy should always be high on the agenda for all future projects. For example, at the start of the project, there was a desire that HS2 sought to achieve a neutral impact on replaceable biodiversity, and a target of ‘No Net Loss’ was used to capture this aspiration.

…

Setting these as requirements at the start of the project, allows nature-based solutions and initiatives to be built into the project as it is developed, and they become part of the thinking within the project’s culture. So, if a drainage designer is designing a balancing pond or a watercourse diversion, they will engage their environmental specialists to think about what habitat can be created in the area to encourage greater biodiversity as part of the development of their design. If this is an intrinsic part of the project, it is much easier to incorporate, and more elegant and complete solutions can be deployed.

No. Stop. Seriously. If we cannot do mass transit projects without ensuring they are net benefits on every possible environmental axis, if we cannot compromise at all? If every decision must be made to maximize superficial local greenness if you want a rail line? Then there will be no rail lines. If the planet is about to burn, act like it.

Somehow our infrastructure costs are going up even more, and quite a lot?

John Arnold: Building costs of every kind of transportation infrastructure have exploded since 2020. A sampling of cost increases in just 3 years:

I-5 Bridge between WA & OR: +56%

Highway construction in TX: +61%

Silicon Valley BART subway: +77%

We must find ways to build faster/cheaper.

Your periodic reminder that we have to go back.

Adam Rossi: The first time I rode on a plane as a kid, people smoked on the flight. I brought a metal cap gun and employees at the airport did a “don’t shoot” joke with me when they handed it back. Family members met us when we got off the plane at the gate. Changes.

Leevon Grant: My first flight [in 1985] was 5yo parents put me on a flight from Kansas City to Rapid City with a change in Denver…by myself…no trouble at all. It was an adventure and we were a proper high trust society.

What is funny is that society today is worthy of much higher trust than society in 1985, except for the part where people would call the cops because the five year old was alone. But, if people did not do that and otherwise acted the way they do today, the world would be a vastly safer, more welcoming place, also you can carry around a cell phone.

If we wanted to, we could indeed go back to 1985 airport security. Also 1985 norms about what kids can do on their own. It would be fine.

Hayden Clarkin: Really expensive transit is almost as good as having no transit at all:

Dudley Snyder: New York State: Complex regulation of retail marijuana will remedy the carceral state

The market: Here are a thousand places to buy unregulated marijuana

New York City: Complex regulation of short-term rentals will remedy the housing shortage

The market: Hold my beer.

US Department of Transportation: As you get ready to celebrate Thanksgiving, make sure you have a sober driver lined up to take you home. Alternatively, plan to take a taxi or use a ride-sharing service to reach your destination safely.

Lacar Musgrove: US Department of Transportation unable to name more than one form of transportation