The fight against “fake news” appears to have overwhelming support in the EU.

According to a new study, 85% of the bloc’s citizens want policymakers to take more action against disinformation, while 89% want increased efforts from platform operators. Just 7% do not feel that stronger responses are required.

The findings emerged from surveys by Bertelsmann Stiftung, a pro-business German think tank with close ties to the EU.

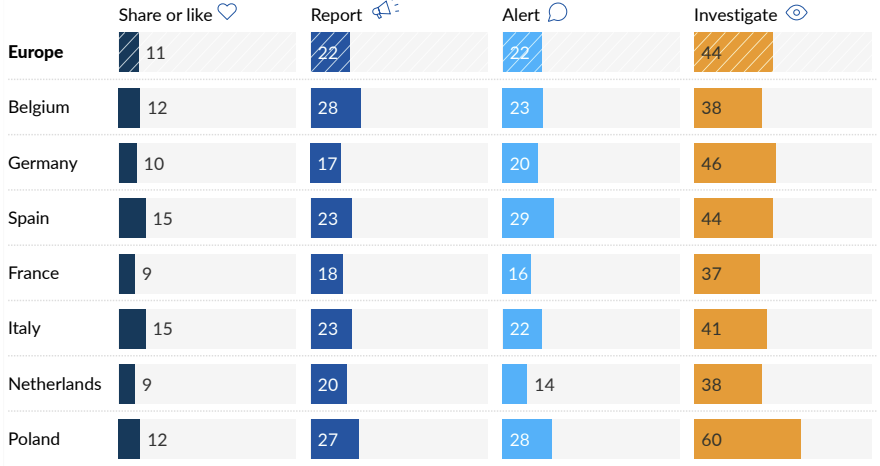

Across the EU, 54% of respondents said they were “often” or “very often” unsure whether information they found online was true. However, only 44% of them had recently fact-checked the content they’d seen.

Younger and more educated people were more likely to take active response to false information. Those in favour of combating disinformation tended to be further to the political left.

In response to the findings, Bertelsmann Stiftung made the following recommendations:

- Establish an effective system for monitoring disinformation both in Germany and across Europe.

- Raise public awareness about the issue of disinformation.

- Promote media literacy among people of all age groups.

- Ensure consistent and transparent content creation on digital platforms.

Such interventions, however, have proven divisive. Around the world, politicians have been accused of exploiting concerns around disinformation to suppress dissent and control narratives.

In the UK, campaigners found that government anti-fake news units have surveilled citizens, public figures, and media outlets for merely criticising state policies. The units also reportedly facilitated censorship of legal content on social media.

The EU, meanwhile, recently adopted the Digital Services Act (DSA), which requires platforms to mitigate the risks of disinformation. Opponents of the law fear that it will lead to state censorship.

Critics have also raised alarm about tech firms acting as arbiters of truth. But Bertelsmann Stiftung’s researchers argue that more intervention is essential.

“People in Europe are very uncertain about which digital content they can trust and which has been intentionally manipulated,” Kai Unzicker, the study author, said in a statement.

“Anyone who wants to protect and strengthen democracy cannot leave people to deal with disinformation on their own.”

Stronger responses could also bolster the growing flock of anti-disinformation startups.

The emerging sector is dominated by the US, but a hub is also emerging in Ukraine, where technologists are turning lessons from fighting Russian propaganda into new businesses.

Published