When Russian troops flooded into Ukraine last year, an army of propagandists followed them. Within hours, Kremlin-backed media were reporting that President Zelenskyy had fled the country. Weeks later, a fake video of Zelenskyy purportedly surrendering went viral. But almost as soon as they emerged, the lies were disproven.

Government campaigns had prepared Ukrainians for digital disinformation. When the crude deepfake appeared, the clip was quickly debunked, removed from social media platforms, and disproven by Zelenskyy in a genuine video.

The incident became a symbol of the wider information war. Analysts had expected Russia’s propaganda weapons to wreak havoc, but Ukraine was learning to disarm them. Those lessons are now fostering a new sector for startups: counter-disinformation.

Like much of Ukrainian society, the country’s tech workers has adopted aspects of military ethos. Some have enlisted in the IT Army of volunteer hackers or applied their skills to defence technologies. Others have joined the information war.

In the latter group are the women who founded Dattalion. A portmanteau of data and battalion, the project provides the world’s largest free and independent open-source database of photo and video footage from the war. All media is classified as official, trusted, or not verified. By preserving and authenticating the material, the platform aims to disprove false narratives and propaganda.

Dattalion’s data collection team leader, Olha Lykova, was an early member of the team. She joined as the fighting reached the outskirts of her hometown of Kyiv.

“We started to collect data from open sources in Ukraine, because there were no international reporters and international press at the time,” Lykova, 25, told TNW in a video call. “In the news, it was not possible to see the reality of what was happening in Ukraine.”

Since the project was established on February 27, 2022 — just three days after the full-scale invasion began — Dattalion has been cited in more than 250 international media outlets, from NBC News to Time. With the mooted addition of a paid subscription service, it could also be monetised — a thorny challenge for the sector.

An emerging sector

Counter-disinformation is not an obvious magnet for consumer cash. Nonetheless, the sector is attracting unusual investor interest.

Governments are particularly enthusiastic backers. In the US, more than $1bn of annual public funding is allocated to fighting disinformation, the Department of State said in 2018. Across the Atlantic, European nations are investing in targeted initiatives. The UK, for instance, created a ‘fake news fund’ for Eastern Europe, while the EU has financed AI-powered anti-disinformation projects.

Big tech is also writing big cheques. Since 2016, Meta alone has ploughed over $100mn into programs supporting its fact-checking efforts. In addition, the social media giant has splashed cash on startups in the space. In 2018, the company spent up to $30mn to buy London-based Bloomsbury AI, with the aim of deploying the acquisition against fake news.

Still, not every tech giant is enthusiastic about corroborating content. Under Elon Musk’s leadership, X (formerly Twitter) has dismantled moderation teams, policies, and features. The approach has been praised by fans of Musk — a self-proclaimed “free speech absolutist” — but triggered spikes in falsehoods on the app.

Alarmed by the controversies, brands have fled the platform in their droves. In July, Musk said X had lost almost half its ad revenue since he bought the company for $44bn last October.

As X grapples with the concerns of advertisers, a wave of tech firms are offering solutions. In the last couple of years, over $300mn has been ploughed into startups that tackle false information, according to Crunchbase data. Two of them have raised over $100mn each: San Francisco-based Primer and Tel Aviv’s ActiveFace. Both companies develop AI tools that can identify disinformation campaigns.

Ukrainian startups are also starting to raise funding— and there are signs that the investments could soon surge.

“Ukraine has been waging an informational struggle for more than 10 years.

In the EU, tech companies now have to comply with the Digital Services Act (DSA), which requires platforms to tackle disinformation. If they don’t, they face fines of up to 6% of their annual global revenue.

X’s DSA obligations have received particular attention. In June, the company received the first “stress test” of the regulatory requirements. After the mock exercise, Musk and Twitter CEO Linda Yaccarino met with EU Commissioner Thierry Breton, who oversees digital policy in the bloc. Breton emphasised a threat that Ukraine recognises all too well.

“I told Elon Musk and Linda Yaccarino that Twitter should be very diligent in preparing to tackle illegal content in the European Union,” he said. “Fighting disinformation, including pro-Russian propaganda, will also be a focus area in particular as we are entering a period of elections in Europe.”

A brief history of the disinformation war

Since the early Soviet Union, Russia has been a pioneer in influence operations. Historians have traced the very word “disinformation” to the Russian neologism “dezinformatsiya.” Some contend that it emerged in the 1920s, as the name for a bureau tasked with deceiving enemies and influencing public opinion.

Defector Ion Mihai Pacepa claimed the term was coined by none other than Joseph Stalin. The Soviet ruler reputedly chose a French-sounding name to insinuate a Western origin. Yet all of these origin stories are disputed. In a world of deception, even etymology is fraught with mistruths.

What isn’t disputed is Russia’s expertise in the field. In the Soviet era, intelligence services merged forgeries, fake news, and front groups into a playbook for political warfare. After the USSR collapsed, old strategies were embedded in new tools. Today’s tricks encompass troll farms spreading support for Kremlin views, bot armies manipulating social media algorithms, and proxy news sites amplifying falsehoods.

Ukraine is all too familiar with the tactics. The country has become a testbed for Russia’s information warfare, which has laid firm foundations for a nascent startup sector.

“It’s an enduring act — Ukraine has been waging an informational struggle against the Russian aggressor for more than 10 years now,” Denis Gursky, a former data advisor to Ukraine’s Prime Minister and the co-founder of tech NGO SocialBoost, told TNW.

“Over this time, Ukraine formed the mechanism of joint work of various sectors, which all together help to repel enemy attacks and protect the information space.”

Gursky is a driving force behind Ukraine’s emerging counter-disinformation industry. In January, he co-organised the 1991 Hackathon: Media, which sought digital solutions to information security challenges. One of the judging criteria was commercial potential.

The responses ranged from war crime trackers and content blockers to news monitors and verification tools. To monetise their concepts, the teams pitched an array of business plans.

Mediawise, a browser extension that adds content and author checks to online news, plans to take payment for premium features, such as alerts and extended article summaries.

OffZMI, an app that protects reliable information from a controversial Ukrainian media law, is eyeing revenues from ads, subscriptions, and NGO partnerships. MindMap, which provides Q&A translations of English-language news reports, envisions a tiered membership model.

Then there is Osavul, which won the hackathon. The company has built a platform that targets an evolving concept in the field: coordinated inauthentic behaviour (CIB).

“The problem is big enough to solve.

A term popularised by Facebook, CIB involves multiple fake accounts collaborating to manipulate people for political or financial ends. To spot this behaviour, Osavul’s AI models detect indicators including account affiliations, posting time patterns, involvement of state media, and content synchronisation.

A key component of the system is a cross-platform approach. This enables Osavu to track CIB across various social networks, online media, and messenger apps. A single campaign can, therefore, be followed from Telegram through X and then into news reports.

One such campaign claimed that NATO had donated infected blood to Ukraine. At the centre of the conspiracy theory was a fake document that purportedly proved the claim.

According to Osavul, the CIB was detected before the campaign gained momentum. Ukrainian government agencies then used the findings to refute the canard.

Ukrainian institutions will get free access to Osavul throughout the war, but the company has also developed a SaaS product. The software targets businesses that are vulnerable to disinformation campaigns, such as pharmaceutical companies. Osavul’s founders, Dmytro Bilash and Dmitry Pleshakov, compare it to conventional cyber security products.

“In the same way organisations protect themselves from malware or phishing, they should protect themselves from disinformation,” Bilash and Pleshakov told TNW via email. “The problem is big enough to solve, and there is a need for suppliers of software products like Osavul.”

With multilingual capabilities and the infrastructure to integrate new data sources, the platform is built to scale. “Budgets for information security are growing, so we see a huge business opportunity in this niche,” Bilash and Pleshakov said.

An early investment suggests their plan has promise. In May, Osavul raised $1mn in a funding round led by SMRK, a Ukrainian VC firm. The cash will finance a move into the international market.

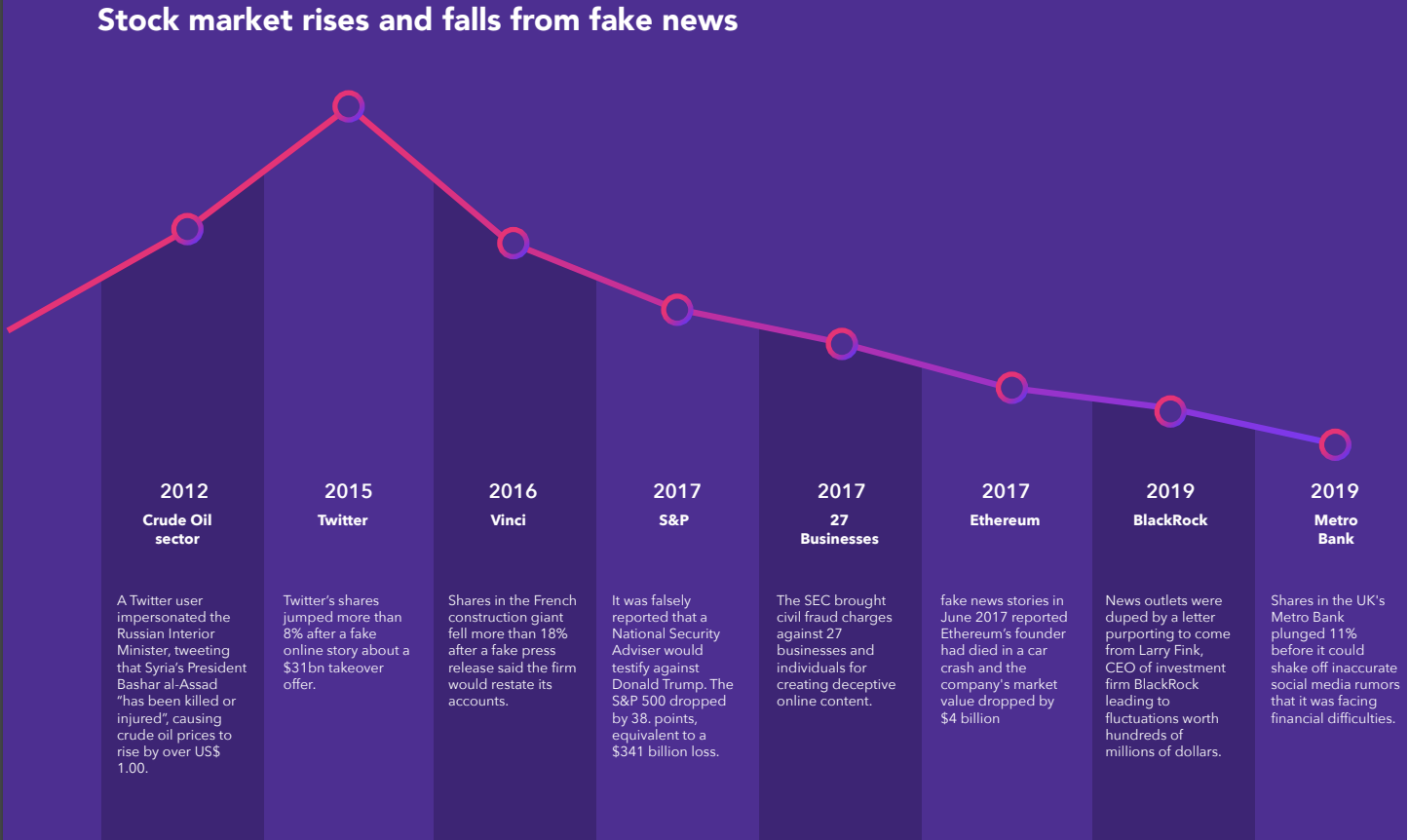

That market could be ripe for expansion. A 2019 study by cybersecurity firm CHEQ and the University of Baltimore estimated that fake news costs the global economy around $78bn (€72bn) each year.

According to the researchers, around half of that figure comes from stock market losses. They cite an eye-popping example from 2017. That December, ABC News erroneously reported that Donald Trump had directed Michael Flynn, his former national security advisor, to contact Russian officials during the 2016 presidential campaign. Following the story, the S&P 500 Index briefly dropped by 38 points — losing investors around $341bn.

ABC didn’t retract the claim until after markets closed. At that point, the losses were down to “only” $51bn (€47bn) for the day.

Beyond the stock market, the study estimated that financial misinformation in the US costs companies $17bn (€15.9bn) each year. Health misinformation, meanwhile, causes annual losses of around $9bn (€8.4bn). The researchers said all their estimates were conservative.

A divisive business

Despite the risks to corporations, the anti-disinformation sector still depends on government backing. That foundation creates both support and frailty.

“The state can have a long-term strategy in the fight against hybrid threats because commercial and public organisations do not have the institutional stability that state bodies have,” Gurksy, the hackathon organiser, told TNW. “But the fight against disinformation is possible only in cooperation with other private and third sectors, which, in fact, have the most experience and tools in this direction.”

Government links are also a prevailing concern about anti-disinformation. Outside of Ukraine, politicians have been accused of exploiting the issue to suppress dissent and control narratives.

In the UK, campaigners found that the government’s anti-fake news units have surveilled citizens, public figures, and media outlets for merely criticising state policies. In addition, the units reportedly facilitated censorship of legal content on social media.

Critics have also been unsettled by tech firms acting as arbiters of truth. But there are now paradoxical concerns about Silicon Valley retreating from these roles.

X, Meta, and YouTube have all been recently accused of reducing efforts to tackle disinformation. In tough economic times, these investments appear to have slipped down the list of priorities. That raises another barrier for Ukraine’s nascent startups: access to capital.

Nonetheless, there are grounds for optimism. Ukraine has a deep pool of tech talent, demonstrably resilient startups, unique experience in fighting propaganda, and strong support from international allies. Sector insiders believe this combination is a powerful launchpad for startups.

Nina Kulchevych, a disinformation researcher and founder of the Ukraine PR Army, expects her country to reap the rewards. She envisions the cottage industry evolving into a global powerhouse.

“Ukraine can be an IT hub for Europe in the creation of technologies for debunking propaganda and spreading disinformation,” she said.

In an economy devastated by war, the commercial potential of counter-disinformation is a powerful attraction. But it’s a peripheral motive for many Ukrainians in the sector. Olha Lykova, the data collection lead at Dattalion, has a separate focus: exposing the truth about Russia’s war.

“Of course, we hope that Ukraine will win,” she said. “But in any case, it will be harder to rewrite history — because we have the proof.”