Digital twins — virtual replicas of real-world things — are already commonplace in manufacturing, industry, and aerospace. There are highly complex digital models of cities, ports, and power stations — but what about people?

The idea of digital doppelgängers has long been confined to the realm of science fiction. But a new book presented at London’s Science Museum last week suggests the concept could be coming to life.

In Virtual You, Peter Coveney, professor of chemistry and computer science at University College London, and Roger Highfield, science director at London’s Science Museum, show how far researchers have already got in their quest for accurate digital simulations of people.

At the book launch, the authors were joined by leading experts in healthcare digital twins from the University of Oxford, UCL, and the Barcelona Supercomputing Centre (BSC). The panel discussed the opportunities and challenges in creating a digital twin version of the human body, and its implications for medicine.

The BSC has already created virtual models of living cells and whole organs. The most notable example is Alya Red, a digital twin of a heart comprising around 100 million virtual cells.

The <3 of EU tech

The latest rumblings from the EU tech scene, a story from our wise ol’ founder Boris, and some questionable AI art. It’s free, every week, in your inbox. Sign up now!

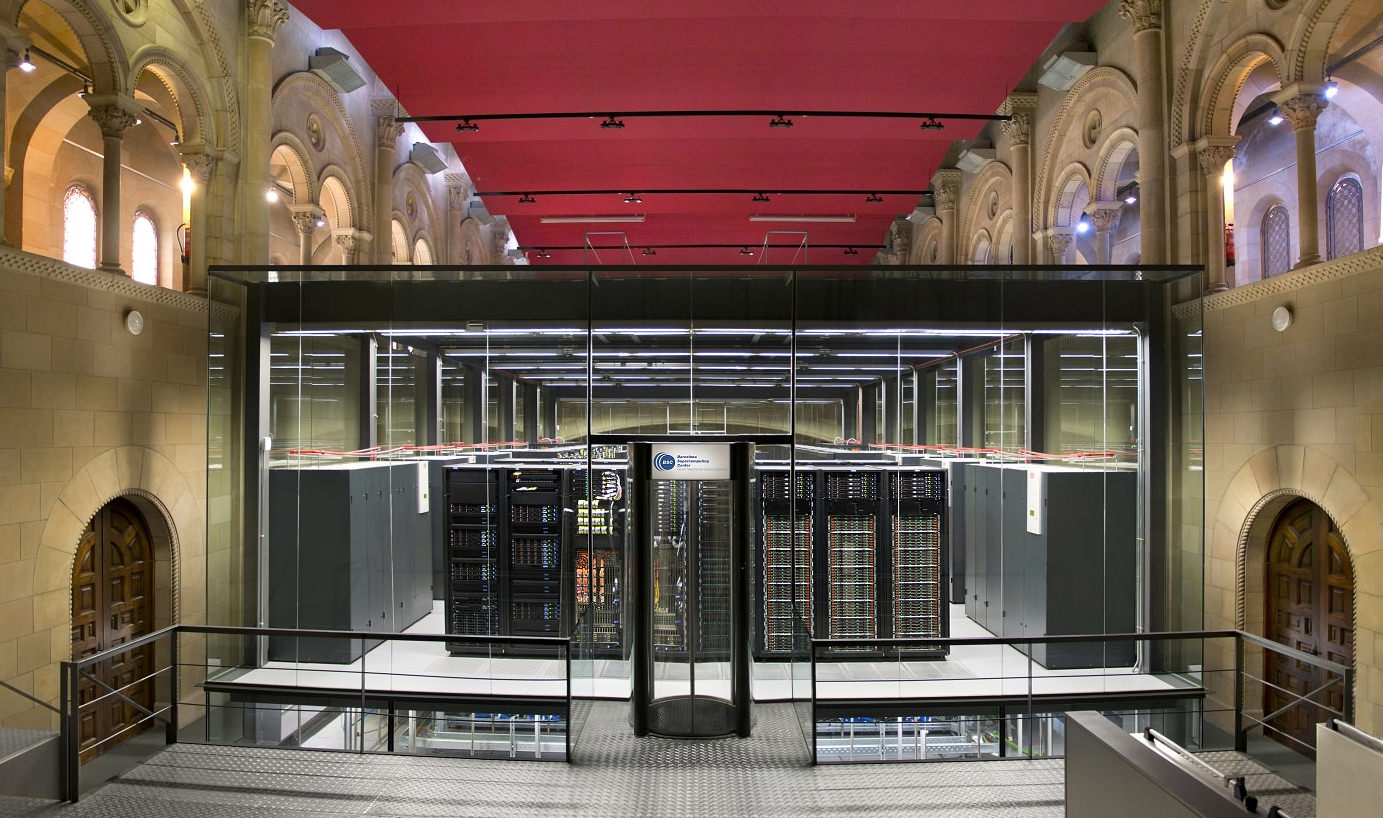

The heart beats not within a person but inside MareNostrum, one of the most powerful supercomputers in Europe. Working with the medical technology company Medtronic, the Alya Red simulations can help position a pacemaker, fine-tune its electrical stimulus, and model its effects.

MareNostrum is located in the Torre Girona chapel, Barcelona. Credit: Karolina Moon Photography.Perhaps one of the most striking examples is Yoon-sun, a 26-year-old Korean woman whose entire circulation — a 95,000km-long network of vessels — has been mapped virtually through an international collaboration using several supercomputers. Researchers are using the model to study blood pressure and the movement of clots throughout the vascular system.

In silico

These digital twins are not just confined to the lab. Several are already in use and, in some cases, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

So far, these models have been deployed mainly for in silico trials — when a drug or disease is tested virtually rather than on real human or animal tissue.

These trials allow companies to test their drug in ‘virtual patients’ before testing them in humans. This can help companies detect a “failure in the making” early on in the drug development cycle, says François-Henri Boissel, CEO of French clinical trial simulation platform Novadiscovery. This can result in significant time and cost savings for companies undertaking clinical trials.

In silico trials also eliminate the ethical issues associated with animal testing, explained Blanca Rodriguez, professor of computational medicine at the University of Oxford, during the panel discussion last Wednesday.

Rodriguez’s team has created a digital twin of a heart that is used to simulate the effects of different drugs and diseases on heart function. In one virtual trial, her team tested the effects of 66 different drugs on over a thousand different heart cell simulations, and were able to predict the risk of abnormal heart rhythms with 89% accuracy. Comparable research on animals was 75% accurate.

These trials can also help fight the next public health emergency. During the COVID-19 pandemic, supercomputers were used to simulate nearly everything, from potential treatments to predicting how the virus might spread, as highlighted in the video below.