While many of us in Europe take it for granted, access to freshwater today, and in the future, is far from guaranteed. Demand is skyrocketing but supply is diminishing. Many of the ways in which water is used are inefficient and antiquated, and climate change is making the entire problem a lot worse.

Europe just had its most severe drought in 500 years. Industries are being forced to shut down or divert water from other sources to maintain operations, while protests have broken out over shortages, most recently in France and Spain. Experts predict that global freshwater demand will outstrip supply by 40% by the end of this decade.

Water technologies — from pulling water from thin air to transforming saltwater into fresh, and everything in between — will be critical in helping industry and society adapt to this new reality.

Unfortunately, water tech still receives a small fraction of the total climate tech funding. Out of some €50bn invested in climate tech globally in 2021, just €430m — less than 1% — was allocated for water tech.

The <3 of EU tech

The latest rumblings from the EU tech scene, a story from our wise ol’ founder Boris, and some questionable AI art. It’s free, every week, in your inbox. Sign up now!

The good news? There is an emerging cohort of tech startups working to prevent the impending water crisis, and investors are beginning to catch on.

Doing more with less

From source to treatment to tap – a lot of money, energy, and resources go into supplying the water we use each day. Shockingly, up to half of this water is lost due to leaky pipes. Another big chunk is lost due to inefficient use, and in most countries, water is never reused. But as water scarcity increases, so does the need to start doing more with less.

One company catering to an up-and-coming segment of water-conscious homeowners is Sweden-based Orbital Systems. The startup, which has raised €65m to date, has developed a shower system inspired by NASA that reuses water in a closed loop. But don’t worry, the shower is equipped with sensors that detect urine or other unsavoury liquids, which get filtered out before the water is reused — thank god.

The company claims its “shower of the future” saves 90% of water and 80% of energy compared to a regular unit. While the systems aren’t cheap — at $4k (€3,680) a pop — Orbital says that homeowners could save $1,100 (€1,011) per year in water bills.

But you don’t necessarily need hardware to cut water use. Belgium-based startup Shayp’s AI-powered software can detect whether a building is leaky and find the most likely source. Data from the building’s existing water metres gets pulled into the Shayp platform and then AI automatically classifies leaks in order of importance.

Buildings, which are some of the EU’s biggest water users, sign a five-year SaaS contract with Shayp, pay 5% of their water bill and in return, reduce their water consumption by 20% on average. “Buildings can significantly reduce their usage and make huge water and cost savings simply through optimisation – no new infrastructure is required,” says CEO Alexandre McCormack.

Shayp is one of many emerging startups harnessing the power of data to help industry and society manage water more sustainably.

Liquid data

Agriculture accounts for around 70% of all freshwater withdrawals globally, a whopping 60% of which is wasted due to inefficient irrigation and planting methods.

Higher resolution data can go a long way in helping farmers optimise their water consumption and free up more water for other critical uses. Constellr, a spin-off from Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute, raised $10mn in seed funding in November to do just that.

Constellr’s tech comprises a fleet of microsatellites equipped with thermal and hyperspectral imaging instruments that gather high-resolution land surface temperature data on a daily basis. The data is used to compile heat maps that illustrate crop stress and water availability at a sub-field level, helping farmers predict a drought ahead of time, or adjust their irrigation regimes based on water availability.

Constellr launched its first satellite into space last year. Within the next five years, it aims to save 60 billion litres of water while generating “billions” in gross profits for farmers.

While Constellr is helping farmers adapt to a lack of water, further north is a startup tapping AI to help businesses and governments deal with too much of it.

Founded in 2020 by a team of Norwegian data scientists and geologists, 7Analytics helps municipalities and businesses better predict flooding — a problem which causes tens of billions of euros in damages each year in Europe alone.

“Our platform can tell you if a flood will occur in your area of interest and issue alerts 72 hours in advance so you can take all the necessary actions to protect employees and assets,” CCO and co-founder Jonas Aas Torland, told TNW in an interview.

Finding new sources

Earlier this year, Elon Musk pronounced water scarcity a “non-issue” because the “world is 70% water” and “desalination is absurdly cheap.”

It’s concerning @elonmusk on @billmaher thinks “there’s plenty of water”, desalination will fix everything. To replace river basin inflows from glacial loss we’ll need ~50x more desal globally, and then in most cases have to pump it 1000+ miles inland: pic.twitter.com/1XFjuswXqa

— Marcus Gibson (@Marcusgibson) April 29, 2023

Yes, Elon, the world is covered in water, but only 0.3% of it is suitable for use. And as for desalination being absurdly cheap? Not so much. Turning saltwater into fresh remains significantly more expensive than sourcing it straight from a river, lake, or under the ground. What the Tesla boss also failed to mention is that desalination is extremely energy intensive, with most plants today being fossil-fuelled.

Luckily, hot countries get a lot of sun and the price of solar power is plummeting, which has given rise to a segment of startups pushing cleaner and cheaper alternatives.

Desolenator, hailing from the Netherlands, has been working on this kind of tech for almost 10 years. Desolenator’s system uses a ‘hybrid’ type of solar panel which is a combination of regular PV and solar thermal technology slated to be four times more efficient than regular panels — bringing down the cost of the final product: fresh water.

Desolenator launched its first fully operational solar thermal desalination plant in Dubai last year. The system has a capacity of 20,000 litres per day and can produce potable water at less than $0.02 per litre — and these costs are expected to go down as the technology scales up.

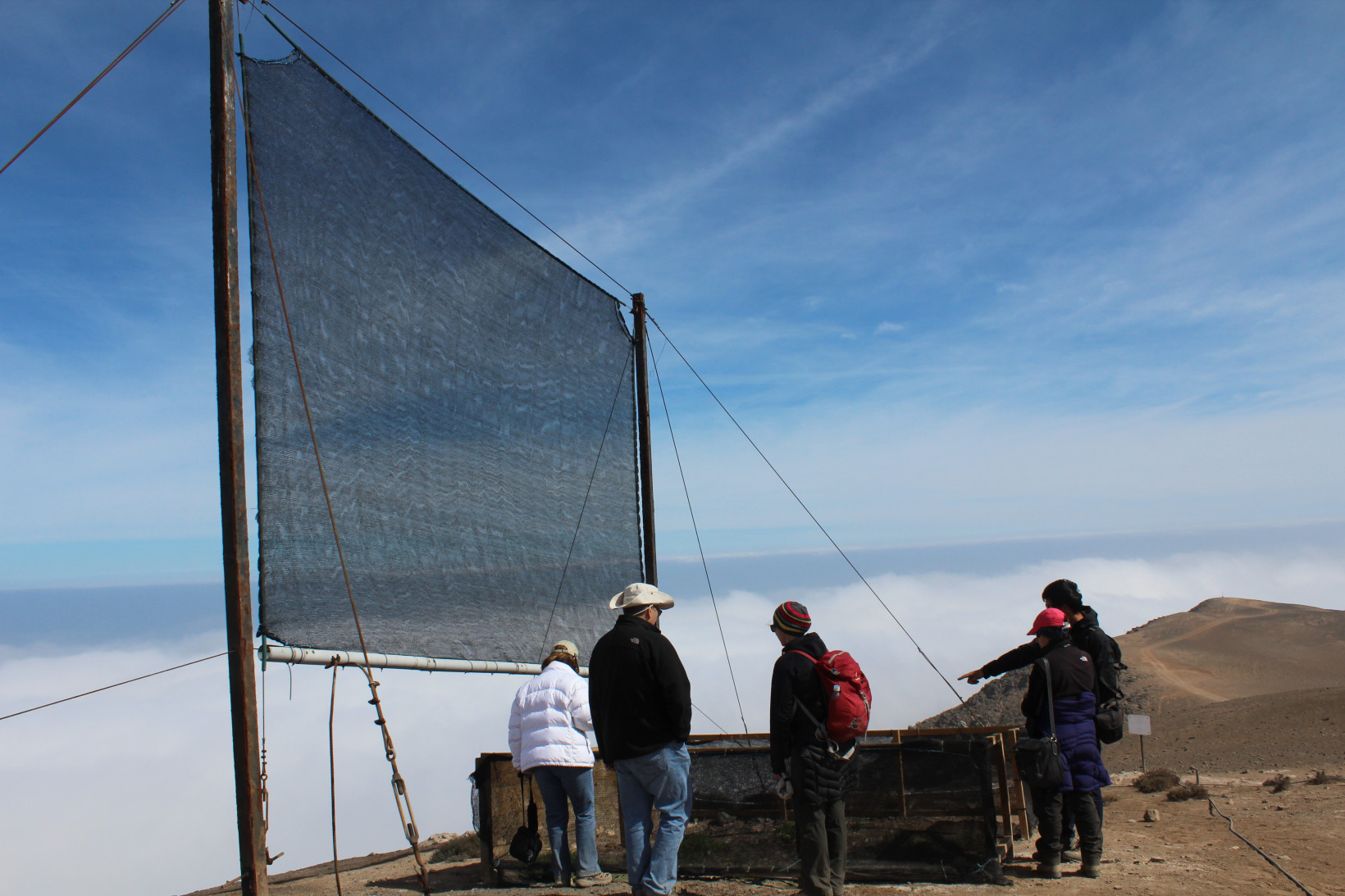

Another option, especially for remote communities, is extracting water from the air — also known as atmospheric water generation (AWG). Records of AWG date back to the Incan empire, which used so-called ‘fog fences’ to capture moisture from the clouds that flow over the Andes Mountains.

Aquaseek, a spin-off from Italy’s Politecnico di Torino and Princeton University, is hard at work bringing a modern touch to this old-school technology. The startup has developed a prototype AWG machine that captures moisture from the air even at very low levels of humidity, like in the desert.

Thanks to two exclusive patents (one held 100% by the Politecnico di Torino, the other shared equally with Princeton University), the machine can extract moisture while consuming much less energy than technologies currently in use.

Capital flows

Mobilising private investment in this nascent water tech ecosystem will be crucial if we are to bring these solutions into the mainstream. But there are still a number of hurdles to overcome.

“Backing startups with innovations for the so-called ‘water industry’ — meaning drinking water and wastewater utilities — has simply not been an actionable area of investment for VCs,” John Robinson, partner Mazarine, a technology VC specialising in water risk, tells TNW from his office in London.

This is partly to do with the fact that water sold by drinking water utilities, unlike energy, is cheap (for now), and is largely seen as a public good rather than an investment opportunity. Moreover, drinking water is typically managed by public utilities who, says Robinson, “lack an appetite for innovation.”

To get the attention of VC cheque books, Robinson suggests water tech startups broaden their horizons and forge a way in industries where water quality and quantity challenges are a headache, or an operational, regulatory, or branding risk.

While water tech investment is still nowhere near the level it needs to be at, there are glimmers of hope. More and more startups are entering the space, and investment rounds are on the rise. European VCs invested €275m into water tech startups in 2022, up from $135m in 2021.

Water tech-focused funds in Europe, such as Amsterdam-based PuraTerra and Switzerland’s Emerald Technology Ventures are closing bigger and bigger rounds, while across the Atlantic, US-based startup Gradiant became the first-ever water tech startup to reach unicorn status last month after a $225m raise.

Gradiant was co-founded by two MIT graduates, Anurag Bajpayee and Prakash Govindan, who have secured no less than 250 patents for their technology, which allows customers to purify and reuse large amounts of water. The startup is tackling all verticals of water treatment — from sewage to toxic chemicals and has already secured big-name clients including chipmakers TSMC and Micron, and carmakers Hyundai and BMW.

“As global manufacturing and supply chains continue to advance, they demand more and more water resources which are increasingly rare and finite,” said John Arnold, Founder of Centaurus Capital, who co-led the record-breaking round alongside BoltRock Holdings.

Back in Europe, things are a little bit more sluggish. Water tech startups on the continent have lower valuations than their US counterparts, and the EU has ringfenced little funding for water technologies, unlike the US with its landmark Inflation Reduction Act.

“Investors are still cautious of betting on water startups,” Gaetane Suzenet, head of the European Water Tech Accelerator, tells TNW. One of the biggest barriers, says Suzenet, is the lack of major exits, which would give investors the confidence to commit.

Five companies have entered the accelerator since it started in 2020. The programme aims to expand this pool to between 25 to 40 companies and make them “European champions.”

“We want to make innovation the norm, explore new financing models, and encourage successful exits to show other startups and investors that water tech is a viable opportunity,” Suzenet says.

Accelerators like this are a step in the right direction but will be a drop in the ocean without increased government support and a change in perspective from the investment community.

While cash for water tech has historically been more of a trickle than a flood, as Europe braces for yet another drought this summer, there has never been a better time for VCs to participate in the growth stories of early-stage water tech companies.

“It’s about looking at the water in a different way,” says Robinson. “Water tech is not just about making utilities more efficient, it’s about preparing industry and society for water-related risks as a result of our new climate reality.”