💦 —

The basic urge to pee is surprisingly complex and can go awry as we age.

You’re driving somewhere, eyes on the road, when you start to feel a tingling sensation in your lower abdomen. That extra-large Coke you drank an hour ago has made its way through your kidneys into your bladder. “Time to pull over,” you think, scanning for an exit ramp.

To most people, pulling into a highway rest stop is a profoundly mundane experience. But not to neuroscientist Rita Valentino, who has studied how the brain senses, interprets, and acts on the bladder’s signals. She’s fascinated by the brain’s ability to take in sensations from the bladder, combine them with signals from outside of the body, like the sights and sounds of the road, then use that information to act—in this scenario, to find a safe, socially appropriate place to pee. “To me, it’s really an example of one of the beautiful things that the brain does,” she says.

Scientists used to think that our bladders were ruled by a relatively straightforward reflex—an “on-off” switch between storing urine and letting it go. “Now we realize it’s much more complex than that,” says Valentino, now director of the division of neuroscience and behavior at the National Institute of Drug Abuse. An intricate network of brain regions that contribute to functions like decision-making, social interactions, and awareness of our body’s internal state, also called interoception, participates in making the call.

In addition to being mind-bogglingly complex, the system is also delicate. Scientists estimate, for example, that more than 1 in 10 adults have overactive bladder syndrome—a common constellation of symptoms that includes urinary urgency (the sensation of needing to pee even when the bladder isn’t full), nocturia (the need for frequent nightly bathroom visits) and incontinence. Although existing treatments can improve symptoms for some, they don’t work for many people, says Martin Michel, a pharmacologist at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, who researches therapies for bladder disorders. Developing better drugs has proven so challenging that all major pharmaceutical companies have abandoned the effort, he adds.

Recently, however, a surge of new research is opening the field to fresh hypotheses and treatment approaches. Although therapies for bladder disorders have historically focused on the bladder itself, the new studies point to the brain as another potential target, says Valentino. Combined with studies aimed at explaining why certain groups, such as post-menopausal women, are more prone to bladder problems, the research suggests that we shouldn’t simply accept symptoms like incontinence as inevitable, says Indira Mysorekar, a microbiologist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. We’re often told such problems are just part of getting old, particularly for women—“and that’s true to some extent,” she says. But many common issues are avoidable and can be treated successfully, she says: “We don’t have to live with pain or discomfort.”

A delicate balance

The human bladder is, at the most basic level, a stretchy bag. To fill to capacity—a volume of 400 to 500 milliliters (about 2 cups) of urine in most healthy adults—it must undergo one of the most extreme expansions of any organ in the human body, expanding roughly sixfold from its wrinkled, empty state.

To stretch that far, the smooth muscle wall that wraps around the bladder, called the detrusor, must relax. Simultaneously, sphincter muscles that surround the bladder’s lower opening, or urethra, must contract, in what scientists call the guarding reflex.

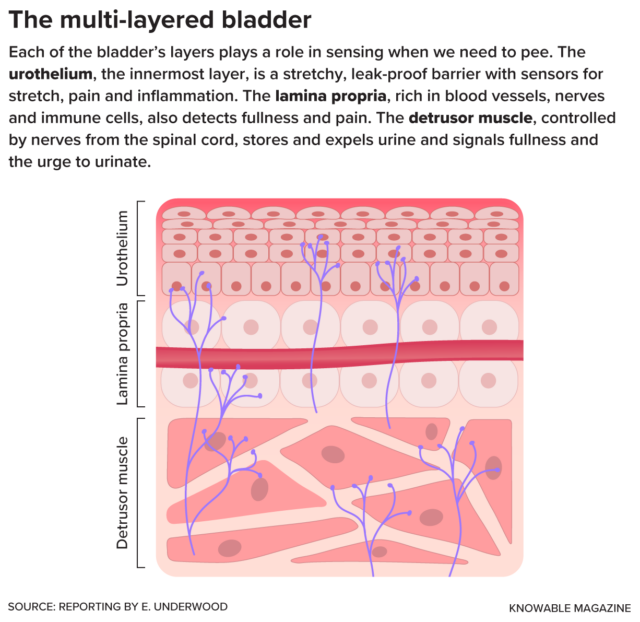

Enlarge / It’s not just sensory neurons (purple) that can detect stretch, pressure, pain and other sensations in the bladder. Other types of cells, like the umbrella-shaped cells that form the urothelium’s barrier against urine, can also sense and respond to mechanical forces — for example, by releasing chemical signaling molecules such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) as the organ expands to fill with urine.

Filling or full, the bladder spends more than 95 percent of its time in storage mode, allowing us to carry out our daily activities without leaks. At some point—ideally, when we decide it’s time to pee—the organ switches from storage to release mode. For this, the detrusor muscle must contract forcefully to expel urine, while the sphincter muscles surrounding the urethra simultaneously relax to let urine flow out.

For a century, physiologists have puzzled over how the body coordinates the switch between storage and release. In the 1920s, a surgeon named Frederick Barrington, of University College London, went looking for the on-off switch in the brainstem, the lowermost part of the brain that connects with the spinal cord.

Working with sedated cats, Barrington used an electrified needle to damage slightly different areas in the pons, part of the brainstem that handles vital functions like sleeping and breathing. When the cats recovered, Barrington noticed that some demonstrated a desire to urinate—by scratching, circling, or squatting—but were unable to voluntarily go. Meanwhile, cats with lesions in a different part of the pons seemed to have lost any awareness of the need to urinate, peeing at random times and appearing startled whenever it happened. Clearly, the pons served as an important command center for urinary function, telling the bladder when to release urine.