According to WHO, people with disabilities represent 16% of the world population. They also find transportation 15 times more challenging than non-disabled individuals. But for mobility to truly be sustainable, it has to go beyond reducing emissions; it has to be inclusive and cater for every member of society.

To this end, technology represents a beacon of hope as much as an invaluable tool. To find out more about its role in enabling universally accessible transportation, I spoke with Jonathan Chacón Barbero, Senior Accessibility Software Engineer at Cabify.

“Technology helps us overcome our limits.

Chacón Barbero joined the ride-hailing scaleup in 2019 and is the person behind the accessibility menu of its app. He has led a multi-year-long career in the design and development of accessible applications, and has worked as an accessibility consultant and lecturer. He is also amongst the few blind software engineers in Europe.

The <3 of EU tech

The latest rumblings from the EU tech scene, a story from our wise ol’ founder Boris, and some questionable AI art. It’s free, every week, in your inbox. Sign up now!

“The first time I got a personal computer as a child, it was love at first sight,” Chacón Barbero says. “That’s when I decided I wanted to be a computer scientist.”At the age of five he built his first software programme, and at the age of nine, he decided to focus on hardware.

Chacón Barbero could see with his right eye until he was 15 years old, at which point he fully lost his vision, leading him to work on software instead.

“The worst moment in my life was when I became blind and I had to be out of technology for three months,” he recalls. “I didn’t know braille. I didn’t understand computers for blind people. I didn’t know anything about the blind world. I had to understand and study everything. I think at that moment, I set my mind for the rest of my life.”

He emphasises that from this point onwards, technology acquired a double meaning in his life: it was no longer just a passion, but also a tool to address challenges related to his condition.

“Technology helps us overcome our limits,” he adds. and And that’s what he set out to do.

Accessibility barriers and impact

The transportation challenges people with disabilities face go far beyond the lack of accessible ramps. Among others, they include inaccessible vehicles; poorly designed curbs, crosswalks, and sidewalks; and non-existent or inaccessible signage, wayfinding, and journey planning information.

Furthermore, studies have shown that social and infrastructural barriers render specific transport modes unavailable to travellers with disabilities and increase journey time. As a result, people with disabilities make fewer trips and travel shorter distances.

“Disability isn’t recognised by all of society yet.

In the UK, for instance, a 2022 survey found that one in five disabled individuals are unable to travel due to the lack of appropriate transport options, while one in four said that negative attitudes from other passengers prevent them from using public transport.

Chacón Barbero shares an example from his experience with using taxi services.

“I have to call a taxi company. I hold on the call as I’m waiting for the driver to arrive. But there is a problem: he doesn’t know that I can’t see the car and I can’t know where the car is. I waste time and money because there hasn’t been direct communication between the driver and the user.”

Putting tech to work

Optimistically, the past few years have seen an increasing number of both public and private initiatives employing new technologies to rise to the challenge of universal accessibility.

For instance, the city of Lyon has developed a public transport app that uses real-time data to assist disabled individuals in getting around, including a feature that helps them identify the most accessible itinerary and the shortest routes.

European startups are also getting active in the field. Think of London-based Wayfindr, which helps vision impaired people travel independently using audio navigation. Or Noteabox whose Button App enables users to press buttons — such as those on pedestrian crossings — through their smartphone.

“Technology is the solution to many accessibility aspects.

Cabify presents another example of how technology can increase inclusiveness in ride-hailing services.

When Chacón Barbero joined the Spanish scaleup, his first step was to build a semantic basement for the app’s digital interface to enable the gradual addition of multiple accessibility features and disability profiles. During the same year, Cabify’s app became 100% accessible for blind people.

In 2020, the company launched its accessibility menu. Since then, it has been adding functionalities and expanding its target groups, such as the hearing impaired, individuals with cognitive disabilities, and the elderly.

“We created a special menu for accessibility in our journey to offer the user the possibility to identify their special needs,” says Chacón Barbero.

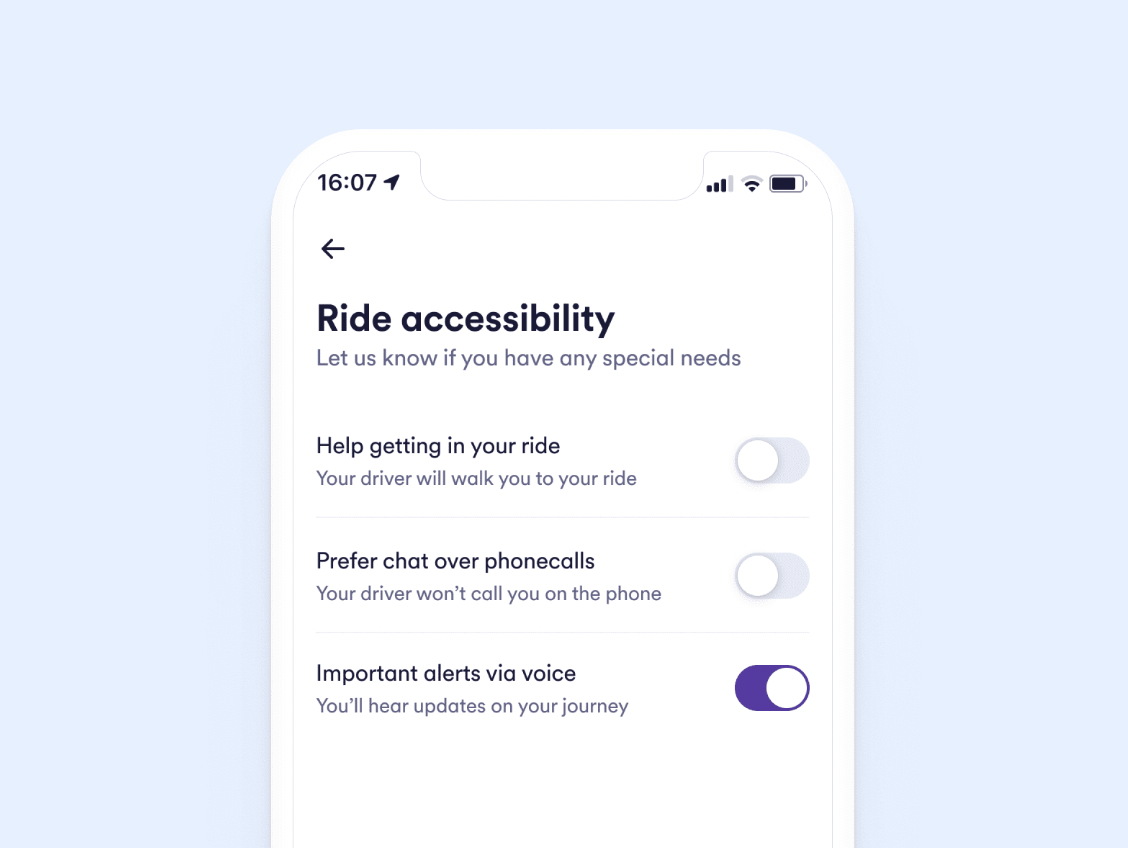

Users can choose between the three options displayed in the image below:

The first option is designed to help the visually impaired, the elderly, and people with reduced mobility inform drivers that they need help reaching the vehicle.

For users with a hearing impairment, the second accessibility option offers the possibility to chat instead of calling. Finally, receiving and playing back important alerts via voice caters for multiple groups, such as the elderly, the visually impaired, and individuals with cognitive impairments.

According to Cabify, by the end of 2022, over 99,000 users had activated at least one of the accessibility menu functionalities. Now, this number exceeds 110,000 users worldwide.

Chacón Barbero says that non-disabled users have also activated the accessibility features as they feel they optimise the experience. He mentions the preference for a bigger font size and the option to chat instead of calling “simply because many people hate phone calls.”

But for Chacón Barbero his work is far from over — on the contrary, he champions the need for continuous improvement. His future plans include adding new in-app functionalities, extending the disability user profiles, and increasing the number of accessible cars.

The biggest barrier to break

For Chacón Barbero the biggest barrier to inclusive mobility is the lack of awareness and social acceptance.

“Accessibility is unknown, because disability is not recognised by all of society yet. Only when you have a friend, a parent, or someone in your environment with disabilities, do you understand what accessibility is. And that’s the problem,” he says.

Eurostat’s numbers are telling: in 2022, 29.7% of the EU population with disabilities aged over 16 were at higher risk from poverty or social exclusion.

Chacón Barbero hopes that, in the future, society will be more inclusive and recognise that people with disabilities are, above all, people. He believes that the younger generations can drive change forward by further embracing individuals who are different and diverse.

“Technology is the solution to many aspects related to accessibility, but it has its limits,” Chacón Barbero concludes, pointing to the need for human action as well. “The solution isn’t only technology. The solution is technology for people and with people.”