Where does it go? It goes up! —

Bizarre design uses a solar-powered motor that’s optimized for weight.

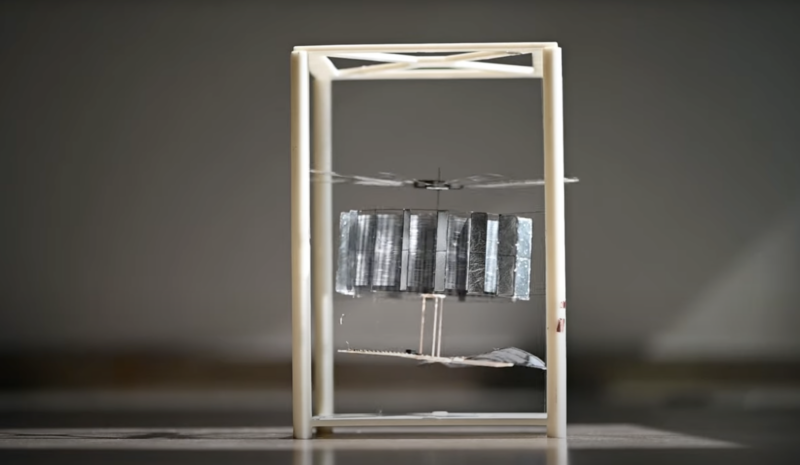

Enlarge / The CoulombFly doing its thing.

On Wednesday, researchers reported that they had developed a drone they’re calling the CoulombFly, which is capable of self-powered hovering for as long as the Sun is shining. The drone, which is shaped like no aerial vehicle you’ve ever seen before, combines solar cells, a voltage converter, and an electrostatic motor to drive a helicopter-like propeller—with all components having been optimized for a balance of efficiency and light weight.

Before people get excited about buying one, the list of caveats is extensive. There’s no onboard control hardware, and the drone isn’t capable of directed flight anyway, meaning it would drift on the breeze if ever set loose outdoors. Lots of the components appear quite fragile, as well. However, the design can be miniaturized, and the researchers built a version that weighs only 9 milligrams.

Built around a motor

One key to this development was the researchers’ recognition that most drones use electromagnetic motors, which involve lots of metal coils that add significant weight to any system. So, the team behind the work decided to focus on developing a lightweight electrostatic motor. These rely on charge attraction and repulsion to power the motor, as opposed to magnetic interactions.

The motor the researchers developed is quite large relative to the size of the drone. It consists of an inner ring of stationary charged plates called the stator. These plates are composed of a thin carbon-fiber plate covered in aluminum foil. When in operation, neighboring plates have opposite charges. A ring of 64 rotating plates surrounds that.

The motor starts operating when the plates in the outer ring are charged. Since one of the nearby plates on the stator will be guaranteed to have the opposite charge, the pull will start the rotating ring turning. When the plates of the stator and rotor reach their closest approach, thin wires will make contact, allowing charges to transfer between them. This ensures that the stator and rotor plates now have the same charge, converting the attraction to a repulsion. This keeps the rotor moving, and guarantees that the rotor’s plate now has the opposite charge from the next stator plate down the line.

These systems typically require very little in the way of amperage to operate. But they do require a large voltage difference between the plates (something we’ll come back to).

When hooked up to a 10-centimeter, eight-bladed propeller, the system could produce a maximum lift of 5.8 grams. This gave the researchers clear weight targets when designing the remaining components.

Ready to hover

The solar power cells were made of a thin film of gallium arsenide, which is far more expensive than other photovoltaic materials, but offers a higher efficiency (30 percent conversion compared to numbers that are typically in the mid-20s). This tends to provide the opposite of what the system needs: reasonable current at a relatively low voltage. So, the system also needed a high-voltage power converter.

Here, the researchers sacrificed efficiency for low weight, arranging a bunch of voltage converters in series to create a system that weighs just 1.13 grams, but steps the voltage up from 4.5 V all the way to 9.0 kV. But it does so with a power conversion efficiency of just 24 percent.

The resulting CoulombFly is dominated by the large cylindrical motor, which is topped by the propeller. Suspended below that is a platform with the solar cells on one side, balanced out by the long, thin power converter on the other.

Meet the CoulombFly.

To test their system, the researchers simply opened a window on a sunny day in Beijing. Starting at noon, the drone took off and hovered for over an hour, and all indications are that it would have continued to do so for as long as the sunlight provided enough power.

The total system required just over half a watt of power to stay aloft. Given a total mass of 4 grams, that works out to a lift-to-power efficiency of 7.6 grams per watt. But a lot of that power is lost during the voltage conversion. If you focus on the motor alone, it only requires 0.14 watts, giving it a lift-to-power efficiency of over 30 grams per watt.

The researchers provide a long list of things they could do to optimize the design, including increasing the motor’s torque and propeller’s lift, placing the solar cells on structural components, and boosting the efficiency of the voltage converter. But one thing they don’t have to optimize is the vehicle’s size since they already built a miniaturized version that’s only 8 millimeters high and weighs just 9 milligrams but is able to generate a milliwatt of power that turns its propeller at over 15,000 rpm.

Again, all this is done without any onboard control circuitry or the hardware needed to move the machine anywhere—they’re basically flying these in cages to keep them from wandering off on the breeze. But there seems to be enough leeway in the weight that some additional hardware should be possible, especially if they manage some of the potential optimizations they mentioned.

Nature, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07609-4 (About DOIs).