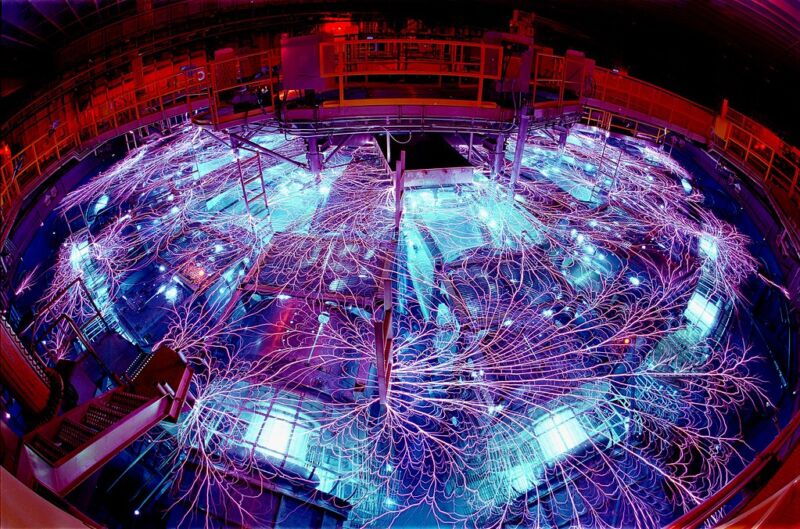

Enlarge / Sandia National Labs’ Z machine in action.

The old joke about the dinosaurs going extinct because they didn’t have a space program may be overselling the need for one. It turns out you can probably divert some of the more threatening asteroids with nothing more than the products of a nuclear weapons program. But it doesn’t work the way you probably think it does.

Obviously, nuclear weapons are great at destroying things, so why not asteroids? That won’t work because a lot of the damage that nukes generate comes from the blast wave as it propagates through the atmosphere. And the environment around asteroids is notably short on atmosphere, so blast waves won’t happen. But you can still use a nuclear weapon’s radiation to vaporize part of the asteroid’s surface, creating a very temporary, very hot atmosphere on one side of the asteroid. This should create enough pressure to deflect the asteroid’s orbit, potentially causing it to fly safely past Earth.

But will it work? Some scientists at Sandia National Lab have decided to tackle a very cool question with one of the cooler bits of hardware on Earth: the Z machine, which can create a pulse of X-rays bright enough to vaporize rock. They estimate that a nuclear weapon can probably impart enough force to deflect asteroids as large as 4 kilometers across.

No nukes! (Just a nuclear simulation)

The Z machine is at the heart of Sandia’s Z Pulsed Power Facility. It’s basically a mechanism for storing a whole lot of electrical energy—up to 22 megajoules—and releasing it nearly instantaneously. Anything in the immediate vicinity experiences extremely intense electromagnetic fields. Among other things, this can be used to heavily ionize materials, like the argon gas used here, generating intense X-rays. These served as a stand-in for the radiation generated by a nuclear weapon.

For an asteroid, the researcher used disks of rock, either quartz or fused silica. (Notably, they only did one sample of each but got reasonably consistent results from them.) Mere mortals might have stuck the disk on a device that could register the force it experienced and left it at that. But these scientists were made of sterner stuff and decided that this wouldn’t really replicate the asteroid experience of floating freely in space.

To mimic that, the researchers held the rock disks in place using thin pieces of foil. These would vaporize almost instantly as the X-ray burst arrives, leaving the rock briefly suspended in the air. While gravity would have its way, the events triggered by the radiation evaporating away a bunch of the rock would be over before the sample experienced any significant downward acceleration. Its movement during this time, and thus the force imparted to it by the evaporation of its surface, was tracked by a laser interferometer placed on the far side of the disk from the X-ray source.

With all that set, all that was left was to fire up the Z machine and vaporize some rock.