Depending on how you count them, China now has roughly 18 types of active space launchers.

China’s new Long March 12 rocket made a successful inaugural flight Saturday, placing two experimental satellites into orbit and testing uprated, higher-thrust engines that will allow a larger Chinese launcher in development to send astronauts to the Moon.

The 203-foot-tall (62-meter) Long March 12 rocket lifted off at 9: 25 am EST (14: 25 UTC) Saturday from the Wenchang commercial launch site on Hainan Island, China’s southernmost province. This was also the first rocket launch from a new commercial spaceport at Wenchang, consisting of two launch sites a short distance from a pair of existing launch pads used by heavier rockets primarily geared for government missions.

The two-stage rocket delivered two technology demonstration satellites into a near-circular 50-degree-inclination orbit with an average altitude of nearly 650 miles (about 1,040 kilometers), according to US military tracking data.

The Long March 12 is the newest member of China’s Long March rocket family, which has been flying since China launched its first satellite into orbit in 1970. The Long March rockets have significantly evolved since then and now include a range of launch vehicles of different sizes and designs.

Versions of the Long March 2, 3, and 4 rockets have been flying since the 1970s and 1980s, burning the same toxic mix of hypergolic propellants as China’s early ICBMs. More recently, China debuted the Long March 5, 6, 7, and 8 rockets consuming the cleaner combination of kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants. These new rockets provide China with a spectrum of small, medium, and heavy-lift launch capabilities.

So many rockets

So, why bother with yet another Long March rocket? One reason is that Chinese officials seek a less expensive rocket to deploy thousands of small satellites for the country’s Internet mega-constellations to rival SpaceX’s Starlink network. Another motivation is to demonstrate the performance of upgraded rocket engines, new technologies, and fresh designs, some of which appear to copy SpaceX’s workhorse Falcon 9 rocket.

Like all of China’s other existing rockets, the Long March 12 configuration that flew Saturday is fully disposable. At the Zhuhai Airshow earlier this month, China’s largest rocket company displayed another version of the Long March 12 with a reusable first stage but with scant design details.

The Long March 12 is powered by four kerosene-fueled YF-100K engines on its first stage, generating more than 1.1 million pounds, or 5,000 kilonewtons of thrust at full throttle. These engines are upgraded, higher-thrust versions of the YF-100 engines used on several other types of Long March rockets.

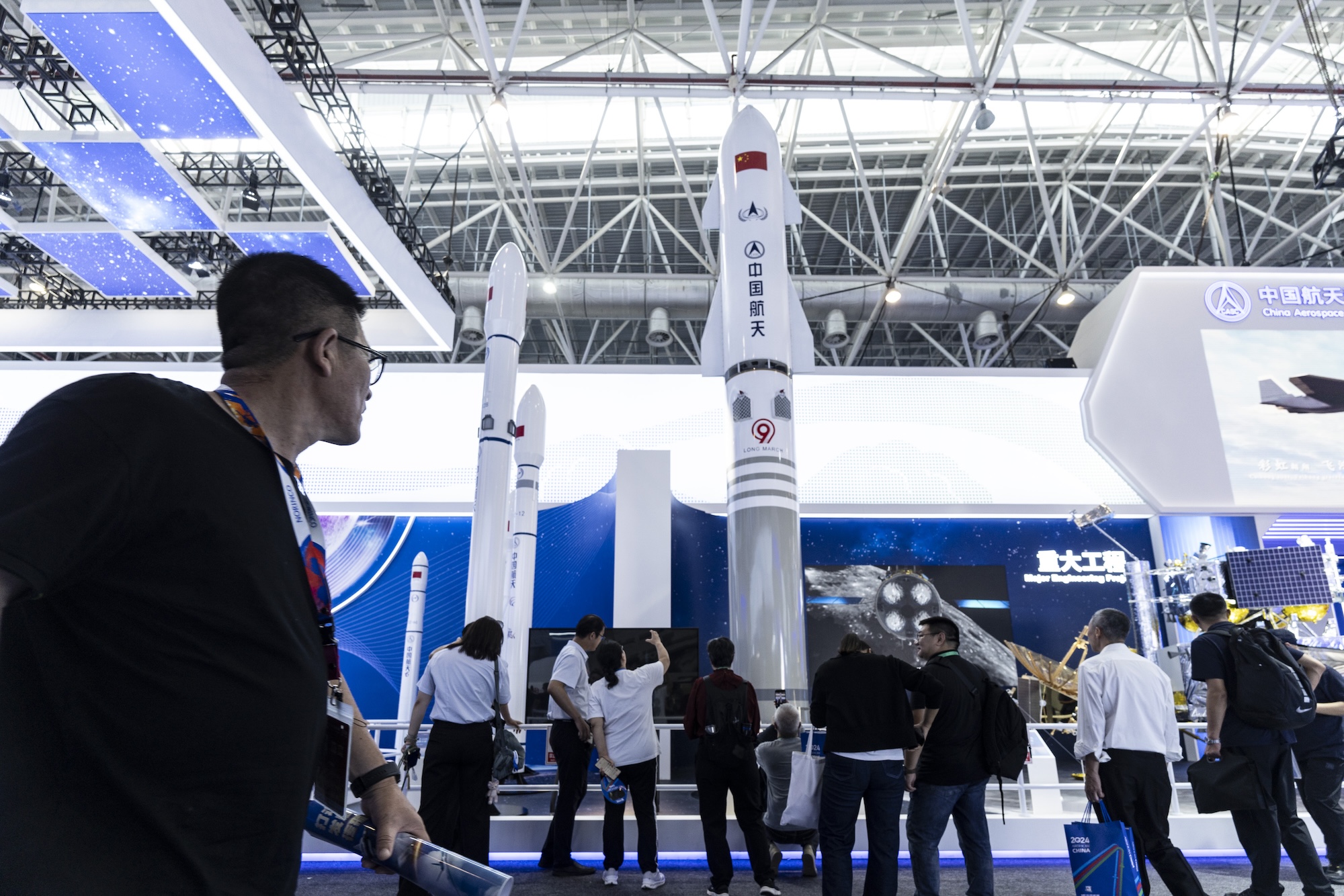

Models of the Long March rockets on display at the China National Space Administration (CNSA) booth during the China International Aviation & Aerospace Exhibition in Zhuhai, China, on November 12, 2024. In this image, models of a future reusable version of the Long March 12 (left) and the super-heavy Long March 9 (right) are visible. Credit: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Notably, China will use the YF-100K variant on the heavy-lift Long March 10 rocket in development to launch Chinese astronauts to the Moon. The heaviest version of the Long March 10 will use 21 of these YF-100K engines on its core stage and strap-on boosters. Now, Chinese engineers have tested the upgraded YF-100K in flight, with favorable results from Saturday’s launch.

China is also developing a new crew-rated spacecraft and lunar lander that will launch on Long March 10 rockets, eyeing a human landing on the lunar surface by 2030. The Long March 10 will have a reusable first stage like the Falcon 9, and China is now working on a super-heavy fully reusable rocket that appears to be a clone of SpaceX’s Starship. This Long March 9 rocket, which probably won’t fly until the 2030s, will enable larger-scale sustained lunar exploration by China.

And now, the details

The Long March 12 was developed by the Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology, also known as SAST, one of the two main state-owned organizations in charge of designing and manufacturing Long March rockets. Together with the Beijing-based China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology, SAST is part of the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, the largest government-run enterprise overseeing the Chinese space program.

According to SAST, the Long March 12 is capable of delivering a payload of at least 12 metric tons (26,455 pounds) into low-Earth orbit and about half that to a somewhat higher Sun-synchronous orbit. Two kerosene-fueled YF-115 engines power the Long March 12’s upper stage.

The Long March 12 is also China’s first 3.8-meter (12.5-foot) diameter rocket, which is an optimal match between the width of the booster and lift capability, allowing it to be transported by railway to launch sites across China, according to the state-run Xinhua news agency.

China’s older Long March rocket variants are slimmer and generally require engineers to strap together multiple first-stage boosters in a cluster arrangement to achieve performance similar to the Long March 12. The core of the heavy-lift Long March 5 is around 5 meters in diameter and must be transported by sea.

China’s first Long March 12 rocket on its launch pad before liftoff. Credit: Photo by VCG/VCG via Getty Images

In a post-launch press release, SAST identified several other “technology breakthroughs” flying on the Long March 12 rocket. These include a health management system that can diagnose anomalies in flight and adjust the rocket’s trajectory in real time to compensate for any minor problems. The Long March 12 is also China’s first rocket to use cryogenic helium to pressurize its liquid oxygen tanks, and its tanks are made of an aluminum-lithium alloy to save weight.

The Long March 12 is also the first rocket of its size in the Long March family to be assembled on its side instead of stacked vertically on its launch mount. After integrating the rocket in a nearby hangar, technicians transferred the first Long March 12 to its launch pad horizontally, then raised it vertical with an erector system. This is the same way SpaceX integrates and transports Falcon 9 rockets to the launch pad. SpaceX copied this horizontal integration approach from older Soviet-era rockets, and it offers several advantages, allowing teams to assemble rockets faster without the need for large overhead cranes in tall, cavernous vertical assembly buildings.

A bug or a feature?

We’ve already mentioned the proliferation of different types of Long March rockets, with nine classes of Long March launchers currently in operation. And each of these comes in multiple sub-variants.

This is a starkly different approach from SpaceX, which flies standardized rockets like the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy, which almost always fly in the same configuration, regardless of the payload or destination for each mission. The only exception is when SpaceX launches Dragon crew or cargo capsules on the Falcon 9.

Depending on how you count them, China now has roughly 18 different types of active space launchers. This number doesn’t include the Long March 9 or Long March 10, but it counts all the other Long March configurations, plus numerous small- and medium-class rockets fielded by China’s quasi-commercial space industry.

These startups operate with the blessing of China’s government and, in many cases, got their start by utilizing surplus military equipment and investment from Chinese local or provincial governments. However, the Chinese Communist Party has allowed them to raise capital from private sources, and they operate on a commercial basis, almost exclusively to serve domestic Chinese markets.

In some cases, these launch startups compete for commercial contracts directly with the government-backed Long March rocket family. The Long March 12 could be in the mix for launching large batches of spacecraft for China’s planned satellite Internet networks.

Some of these launch companies are working on reusable rockets similar in appearance to SpaceX’s Falcon 9. All of these rockets, government and commercial, are part of an ecosystem of Chinese launchers tasked with hauling military and commercial satellites into orbit.

The Long March 12 launch Saturday was China’s 58th orbital launch attempt of 2024, and no single subvariant of a Chinese rocket has flown more than seven times this year. This is in sharp contrast to the United States, which has logged 142 orbital launch attempts so far this year, 119 of them by SpaceX’s Falcon 9 or Falcon Heavy rockets.

There are around a dozen US orbital-class launch vehicle types you might call operational. But a few of these, such as Northrop Grumman’s Pegasus XL and Minotaur, and NASA’s Space Launch System, haven’t flown for several years.

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 is now the dominant leader in the US launch industry. Most of the Falcon 9 launches are filled to capacity with SpaceX’s own Starlink Internet satellites, but many missions fly with their payload fairings only partially full. Still, the Falcon 9 is more affordable on a per-kilogram basis than any other US rocket.

In China, on the other hand, none of the commercial launch startups have emerged as a clear leader. When that happens, if China allows the market to function in a truly commercial manner, some of these Chinese rocket companies will likely fold.

However, China’s government has a strategic interest in maintaining a portfolio of rockets and launch sites, same as the US government. For example, Chinese officials said the new launch site at Wenchang, where the Long March 12 took off from over the weekend, can accommodate 10 or more different types of rockets.