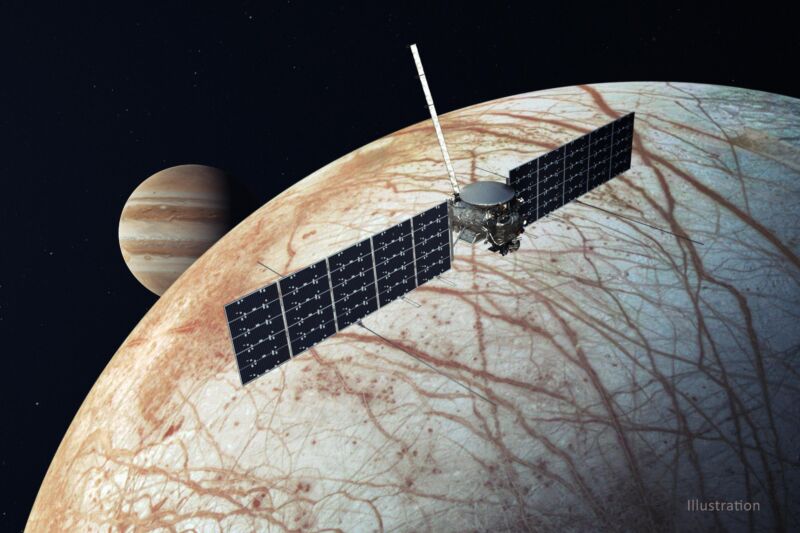

Enlarge / An artist’s illustration of the Europa Clipper spacecraft during a flyby close to Jupiter’s icy moon.

The launch date for the Europa Clipper mission to study the intriguing moon orbiting Jupiter, which ranks alongside the Cassini spacecraft to Saturn as NASA’s most expensive and ambitious planetary science mission, is now in doubt.

The $4.25 billion spacecraft had been due to launch in October on a Falcon Heavy rocket from Kennedy Space Center in Florida. However, NASA revealed that transistors on board the spacecraft may not be as radiation-hardened as they were believed to be.

“The issue with the transistors came to light in May when the mission team was advised that similar parts were failing at lower radiation doses than expected,” the space agency wrote in a blog post Thursday afternoon. “In June 2024, an industry alert was sent out to notify users of this issue. The manufacturer is working with the mission team to support ongoing radiation test and analysis efforts in order to better understand the risk of using these parts on the Europa Clipper spacecraft.”

The moons orbiting Jupiter, a massive gas giant planet, exist in one of the harshest radiation environments in the Solar System. NASA’s initial testing indicates that some of the transistors, which regulate the flow of energy through the spacecraft, could fail in this environment. NASA is currently evaluating the possibility of maximizing the transistor lifetime at Jupiter and expects to complete a preliminary analysis in late July.

To delay or not to delay

NASA’s update is silent on whether the spacecraft could still make its approximately three-week launch window this year, which gets Clipper to the Jovian system in 2030.

Ars reached out to several experts familiar with the Clipper mission to gauge the likelihood that it would make the October launch window, and opinions were mixed. The consensus view was between a 40 to 60 percent chance of becoming comfortable enough with the issue to launch this fall. If NASA engineers cannot become confident with the existing setup, the transistors would need to be replaced.

The Clipper mission has launch opportunities in 2025 and 2026, but these could lead to additional delays. This is due to the need for multiple gravitational assists. The 2024 launch follows a “MEGA” trajectory, including a Mars flyby in 2025 and an Earth flyby in late 2026—Mars-Earth Gravitational Assist. If Clipper launches a year late, it would necessitate a second Earth flyby. A launch in 2026 would revert to a MEGA trajectory. Ars has asked NASA for timelines of launches in 2025 and 2026 and will update if they provide this information.

Another negative result of delays would be costs, as keeping the mission on the ground for another year likely would result in another few hundred million dollars in expenses for NASA, which would blow a hole in its planetary science budget.

NASA’s blog post this week is not the first time the space agency has publicly mentioned these issues with the metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor, or MOSFET. At a meeting of the Space Studies Board in early June, Jordan Evans, project manager for the Europa Clipper Mission, said it was his No. 1 concern ahead of launch.

“What keeps me awake at night”

“The most challenging thing we’re dealing with right now is an issue associated with these transistors, MOSFETs, that are used as switches in the spacecraft,” he said. “Five weeks ago today, I got an email that a non-NASA customer had done some testing on these rad-hard parts and found that they were going before (the specifications), at radiation levels significantly lower than what we qualified them to as we did our parts procurement, and others in the industry had as well.”

At the time, Evans said things were “trending in the right direction” with regard to the agency’s analysis of the issue. It seems unlikely that NASA would have put out a blog post five weeks later if the issue were still moving steadily toward a resolution.

“What keeps me awake right now is the uncertainty associated with the MOSFETs and the residual risk that we will take on with that,” Evans said in June. “It’s difficult to do the kind of low-dose rate testing in the timeframes that we have until launch. So we’re gathering as much data as we can, including from missions like Juno, to better understand what residual risk we might launch with.”

These are precisely the kinds of issues that scientists and engineers don’t want to find in the final months before the launch of such a consequential mission. The stakes are incredibly high—imagine making the call to launch Clipper only to have the spacecraft fail six years later upon arrival at Jupiter.