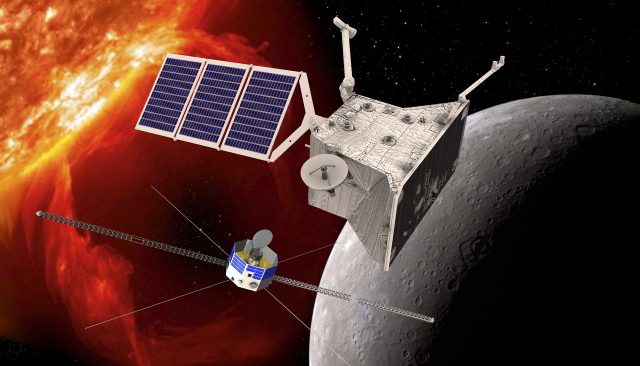

An artist’s rendering of the BepiColombo mission, a joint ESA/JAXA project, which will take two spacecraft to the harsh environment of Mercury.

ESA

This week the European Space Agency posted a slightly ominous note regarding its BepiColombo spacecraft, which consists of two orbiters bound for Mercury.

The online news release cited a “glitch” with the spacecraft that is impairing its ability to generate thrust. The problem was first noted on April 26, when the spacecraft’s primary propulsion system was scheduled to undertake an orbital maneuver. Not enough electrical power was delivered to the solar-electric propulsion system at the time.

According to the space agency, a team involving its own engineers and those of its industrial partners began working on the issue. By May 7 they had made some progress, restoring the spacecraft’s thrust to about 90 percent of its original level. But this is not full thrust, and the root cause of the problem is still poorly understood.

This is an ambitious mission, with an estimated cost of $2 billion. Undertaken jointly with the Japanese space agency, JAXA, BepiColombo launched on an Ariane 5 rocket in October 2018. So there is a lot riding on these thrusters. The critical question is, at this power level, can BepiColombo still perform its primary task of reaching orbit around Mercury?

The answer to this question is not so clear.

A three-part spacecraft

The spacecraft consists of three components. The “transfer module” is where the current problems are occurring. It was built by the European Space Agency and is intended to power the other two components of the spacecraft until October 2025. It is essential for positioning the spacecraft for entry into orbit around Mercury. The other two elements of the mission are a European orbiter, MPO, and a Japanese orbiter, Mio. After their planned arrival in orbit around Mercury in December 2025, the two orbiters will separate and make at least one year’s worth of observations, including the characterization of the small planet’s magnetic field.

The news release is ambiguous about the fate of BepiColombo if full power cannot be restored to its propulsion system.

Ars reached out to the European Space Agency and asked whether BepiColombo can still reach orbit around Mercury in this state. The response, a statement from Elsa Montagnon, the head of mission operations at the space agency, is not entirely clear.

“Thanks for your legitimate questions on the current uncertainty,” Montagnon said. “We are working hard on resolving these uncertainties.”

Gotta have that delta-V

What is clear, she said, is that the current thrust level can support the next critical milestone, BepiColombo’s fourth Mercury swing-by, which is due to occur on September 5 of this year. This is the first of three swing-bys scheduled to happen in rapid succession from September to January that will slow the spacecraft down relative to Mercury.

“This swing-by sequence provides a braking delta-V of 2.4 km/s and provides a change of velocity vector direction with respect to the Sun as required for the trajectory end game in 2025,” Montagnon said.

At present, a team of experts is working on the implications of reduced thrusters for the other two parts of this swing-by sequence and other propulsion needs in 2025.

This transfer module is scheduled to be jettisoned from the rest of the stack in October 2025, and after that the remaining Mercury approach and orbit insertion maneuvers will be carried out with the chemical propulsion subsystem of the European MPO spacecraft.