Previous Economics Roundups: #1, #2, #3

Since this section discusses various campaign proposals, I’ll reiterate:

I could not be happier with my decision not to cover the election outside of the particular areas that I already cover. I have zero intention of telling anyone who to vote for. That’s for you to decide.

All right, that’s out of the way. On with the fun. And it actually is fun, if you keep your head on straight. Or at least it’s fun for me. If you feel differently, no blame for skipping the section.

Last time the headliner was Kamala Harris and her no good, very bad tax proposals, especially her plan to tax unrealized capital gains.

This time we get to start with the no good, very bad proposals of Donald Trump.

This is the stupidest proposal so far, but also the most fun?

(Aside from when he half-endorsed a lightweight version of The Purge?!)

Trump: We will end all taxes on overtime.

The details of the announcement speech at the link are pure gold. Love it.

The economists, he said, told him he would get ‘a whole new workforce.’

Yes, that would happen, and now it’s time for Solve For the Equilibrium. What would you do, if you learned that ‘overtime pay’ meaning anything for hours above forty in a week was now tax free? How would you restructure your working hours? Your reported working hours? How many vacations you took versus how often you worked more than forty hours? The ratio of regular to overtime pay? Whether you were on salary versus hourly? What it would mean to be paid to be ‘on call,’ shall we say?

I used this question as a test of GPT-4o1. Its answer was disappointing, missing many of the more obvious exploitations, like alternating 80 hour work weeks with a full week off combined with double or more pay for overtime. Or shifting people out of salary entirely onto hourly pay.

I often work more than 40 hours a week for real, so I’d definitely be restructuring my compensation scheme. And let’s face it, the ‘for real’ part is optional.

This of course is never going to happen. If it did, it would presumably include various rules and caps to prevent the worst abuses. But even the good version would be highly distortionary, and highly anti-life. You are telling people to intentionally shift into a regime where they work more than 40 hours a week as often as possible, the opposite of what we as a society think is good. This is not what peak performance looks like, even working fully as intended.

Less fun Trump proposals are things like bringing back the SALT deduction (what, why, I am so confused on this one?) and a 10% cap on interest on credit cards. Which would effectively be a ban on giving unsecured credit cards with substantial limits to anyone at substantial risk of not paying it back or require other draconian fees and changes to compensate, and lord help us if actual interest rates ever approached 10%. Larry Summers notes that this is a dramatic price cut on the order of 70% for many customers, as opposed to other proposed price controls that are far less dramatic and thus less destructive, so it would have far more dramatic effects faster. If payday loans are included they’re de facto banned, if not then people will substitute those far worse loans for their no longer available credit cards.

(Fun fact: We do have price controls on debit cards, which turns out mostly fine because there’s no credit risk and it’s a natural monopoly, except now of course the Biden DoJ is bringing an antitrust suit against Visa.)

Then there’s ‘I’m going to bring down auto insurance costs by 50%’ where I could try to imagine how he plans to do that but what would even be the point.

Also there is his plan to ‘make auto loan interest tax deductible’ which is another fun one. Already car companies often make most of their money on financing. The catch is the standard deduction, which you have to give up in order to claim this. If the car loan is the only big item you’ve got, it won’t help you. What you need is some other large deduction, which will usually be a home loan. So this is essentially a gift to homeowners – once you’re deducting your mortgage interest, now you can also deduct your car loan interest. It makes no economic sense, but Elon Musk will love it, and it’s not that much stupider than the mortgage deduction. Of course, what we should actually do is end or phase out the mortgage deduction (as a compromise you could keep existing loans eligible but exclude new ones, since people planned on this), but I’m a realist.

Also there’s Trump’s other proposed huge giveaway and trainwreck, which is a quiet intention to ‘privatize’ Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. I put privatize in air quotes because if you think for one second we would ever allow these two to fail then I have some MBS to sell you. Or buy from you. I’m not sure which. Quite obviously we are backing these two full on ride or die, so this would mean socialized losses with privatized gains and another great financial crisis waiting to happen.

As Arnold Kling suggests, we could and likely should instead greatly narrow the range of mortgages the government backs, and let the private sector handle the rest at market prices. When we back these mortgages, the subsidy is captured by existing homeowners and raises prices, so what are we even doing? Alas, I doubt we will seriously consider that change.

Another note on the unrealized capital gains issue is what happens to IP that pays out over time. For example, Taylor Swift suddenly owns a catalog worth billions, that could gain hundreds of millions in value when interest rates shift. Are you going to force her to pay tax on all that? How is she going to do that without selling the catalog? You want to force her to do that? Or do you want her to find a way to intentionally sabotage the value of the catalog?

We have some good news on the grocery price control front, as Harris has made clear that her plan would not involve global price controls on groceries and widespread food shortages. Instead, it will be modeled on state-level price gouging laws, so that in an emergency we can be sure that food joins the list of things that quickly becomes unavailable at any price, and no one has the incentive to stock up on or help supply badly needed goods during a crisis.

Tariffs are terrible, but not as bad as I previously thought, if there is no retaliation?

Justin Wolfers: Here’s a rule of thumb that Goldman draws from the literature:

Roughly 15% of a tariff is borne by exporters from the other country.

Another 15% results in compressed margins for American importers.

70% of the burden is borne by consumers paying higher prices.

The first 15% is indeed then ‘free money’ and the second 15% is basically fine. So if you were to use the tariff to reduce other taxes, and the other country didn’t retaliate, you’d come out ahead. You get deadweight loss from reduced volume due to the 70%, but you face similar issues at least as much with almost every other tax.

A full-on trade war by the USA alone, however, would be extremely bad (HT MR).

We use an advanced model of the global economy to consider a set of scenarios consistent with the proposal to impose a minimum 60% tariff against Chinese imports and blanket minimum 10% tariff against all other US imports. The model’s structure, which includes imperfect competition in increasing-returns industries, is documented in Balistreri, Böhringer, and Rutherford (2024). The basis for the tariff rates is a proposal from former President Donald Trump (see Wolff 2024). We consider these scenarios with and without symmetric retaliation by our trade partners.

Our central finding is that a global trade war between the United States and the rest of the world at these tariff rates would cost the US economy over $910 billion at a global efficiency loss of $360 billion. Thus, on net, US trade partners gain $550 billion. Canada is the only other country that loses from a US go-it-alone trade war because of its exceptionally close trade relationship with the United States.

…

When everyone retaliates against the United States, the closest scenario here to a US-led go-it-alone global trade war, China actually gains $38.2 billion.

Noah Smith does remind us that no, imports do not reduce GDP. Accounting identities are not real life, and people (including Trump and his top economic advisor) are confusing the accounting identity for a real effect. Yes, some imports can reduce GDP, in particular imports of consumer goods that would have otherwise been bought and produced internally. But it is complicated, and many imports, especially of intermediate goods, are net positive for GDP.

In other campaign rhetoric news, I offer props to JD Vance for pointing out that car seat requirements act as a form of contraception.

The context of his comment was a hearing where people quite insanely proposed to ban lap infants on flights, which the FAA has to fight back against every few years by pointing out that flying is far safer than other transportation.

So such a ban would actively make us less safe by forcing people to drive.

If you want the right job, or a great job, that’s hard. If you want a job at all? That’s relatively easy, if you’re in reasonable health.

Jeremy: Only 4% of working age males “not in the labor force” say they have difficulty finding work. By far the largest reason for dropping out is physical disability and health problems.

A comment points out Jeremy is playing loose here: 4% is who listed this as the primary reason for being out of the labor force. A lot more did have difficulty.

Jeremy: Also, the prime-age employment rate is near all-time highs — some men aren’t in the LF, this is true, but women are employed at by far the highest rate ever. This suggests that the number of jobs isn’t the problem, but something (or things) are making men drop out (see above).

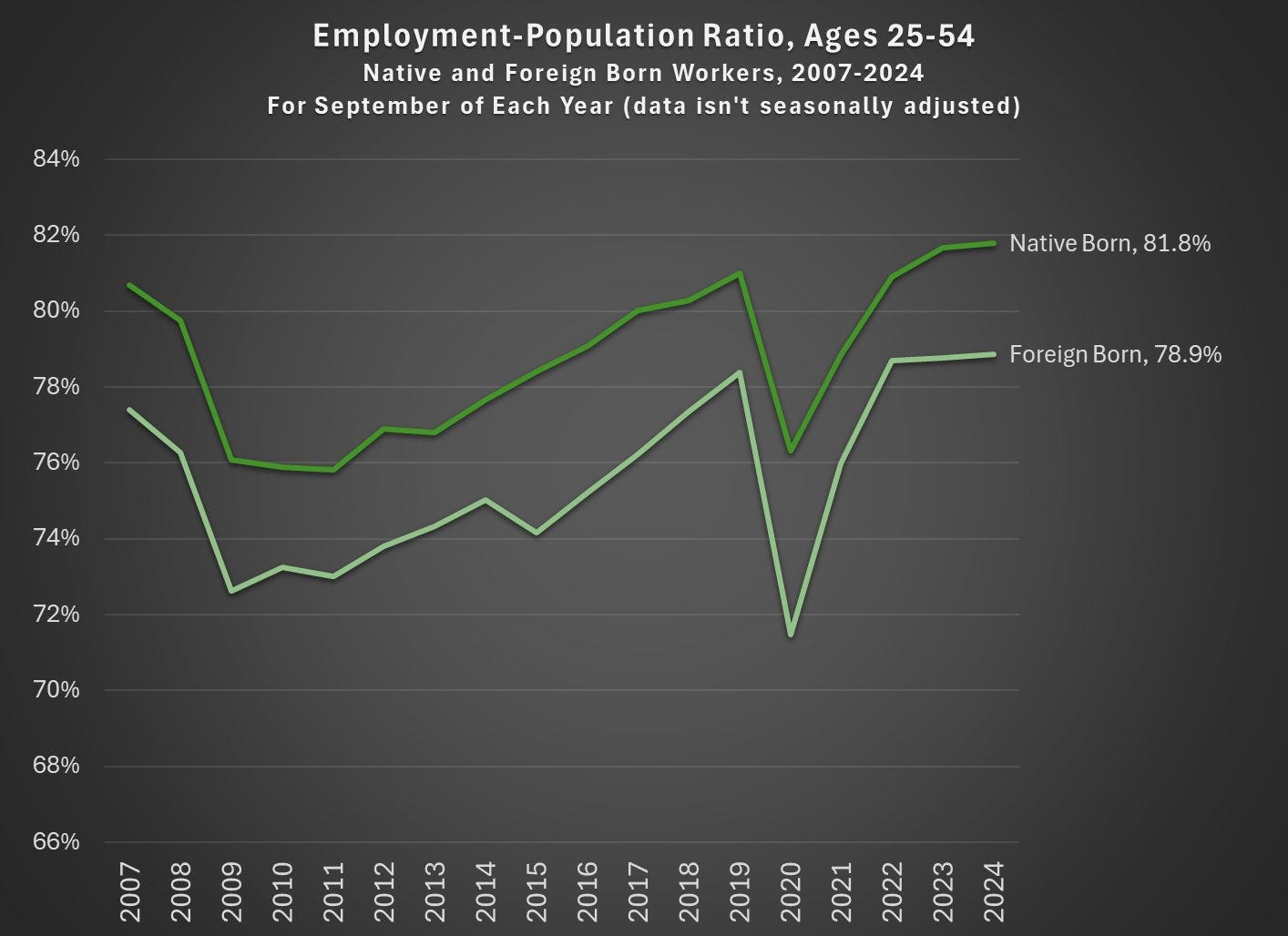

And the prime age employment rate is highest for native-born workers

Yes, a lot of those jobs are terrible. But that has always been true.

Kalshi will pay 4.05% on both cash and open positions, which will adjust with Fed rates. That’s a huge deal. The biggest barrier to long term prediction markets is the cost of capital, which is now dramatically lower.

Election prediction market update: As I write this, Polymarket continues to be the place to go for the deep markets, and they have Trump at 55% to win despite very little news. So we’ve finally broken out of the period where the market odds were strangely 50/50 for a long time, likely for psychological reasons driving traders. The change is also reflected in the popular vote market, with Trump up to 31% there, about 8% above his lows. Nate Silver’s predictions have narrowed, he has Harris at 51% to win, down from a high of 58%.

The move seems rather large given the polls and lack of other events. My interpretation is that the market is both modestly biased in favor of Trump for structural reasons (including that it’s a crypto market and Trump loves crypto) and that the market is taking a no-news-is-good-for-Trump approach.

I haven’t heard anyone think of it that way, but it makes sense to me. Consider the debate. Clearly the debate was good for Harris, including versus expectations. But also the debate was expected to be good for Harris, so before the debate the polls were underestimating Harris in that way. One could similarly say that Harris generally has more opportunity to improve and less chance of imploding or having health issues over the last two months, so her chances go down a little if Nothing Ever Happens.

As many have pointed out, there is little difference between 44% Harris at Polymarket, and 51% Harris at Silver Bulletin. Even if one of them wins decisively, it won’t mean that one of them is right and the other wrong. To conclude that you have to look at the details more carefully.

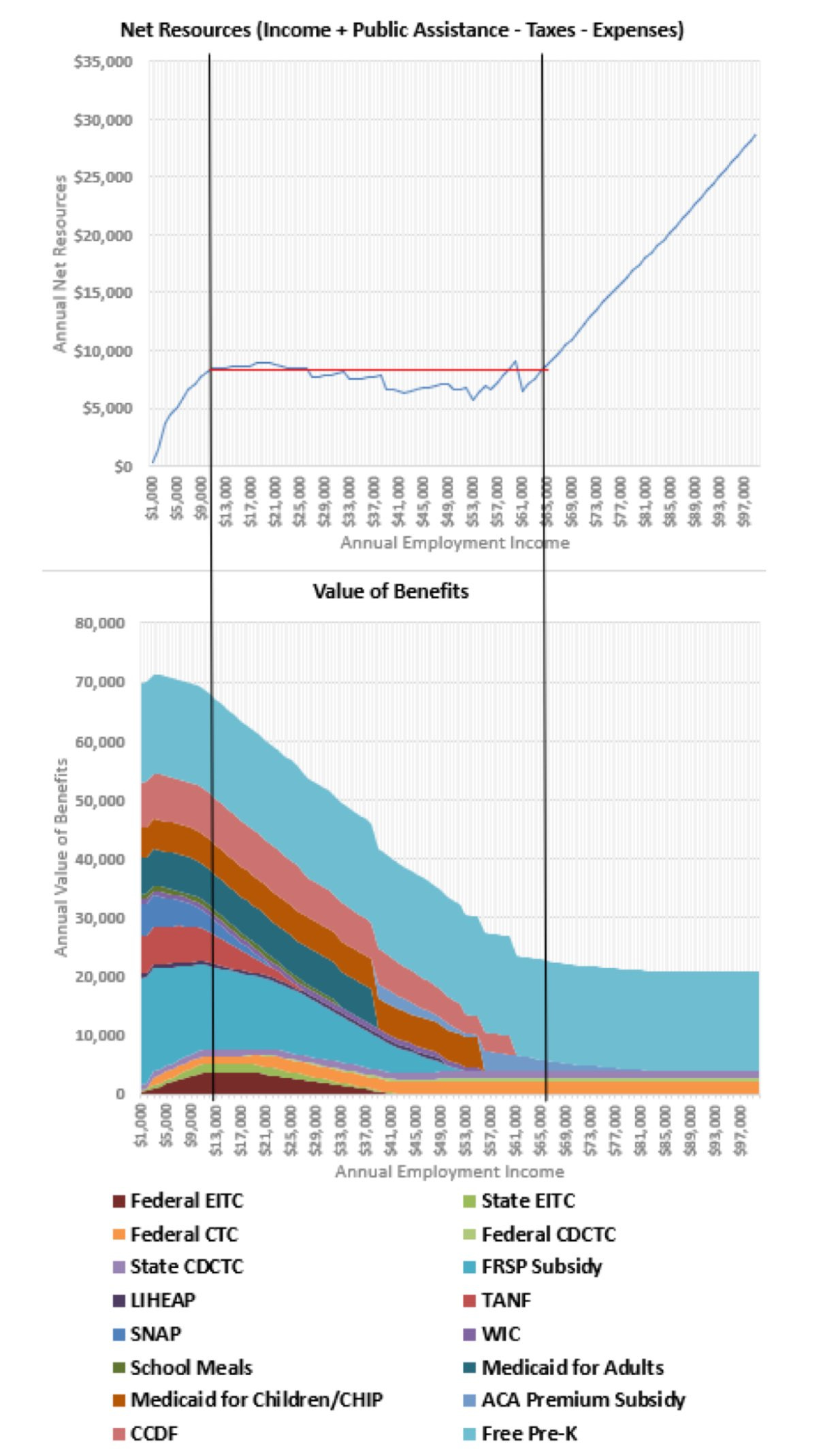

We’ve gone over this before but it bears repeating, and I like the way this got presented this time around. How bad are our marginal tax rates for those seeking to climb into the middle class, once you net out all forms of public assistance, taxes and expenses?

As bad as it gets.

Brad Wilcox: Truly astonishing indictment of our welfare policies fr @AtlantaFed. A single mother in DC can make no gains, financially, as her earnings rise from $11,000 to $65,000 because benefits like food stamps & Medicaid phase in/out as her income rises. Terrible for work/marriage.

Andrew Jobst: Talked to someone who lost their job in the GFC (highly educated, driven, professional credentials). Wanted to start her own business. Commented about how demoralizing it was to hustle all day to earn another dollar, only for her unemployment benefit to drop by a dollar.

Benefits are not ‘as good as cash’ so the problem probably is not quite as bad as ‘100% effective marginal tax rates from $10,000 in income up to $65,000’ but it could be remarkably close, especially in places with high additional state taxes.

Can you imagine what would happen if you took a world like this, and you stopped counting tips as taxable income, as proposed by both candidates?

Effectively, you’d have a ~100% tax rate on non-tip income, but 0% on tips (and Trump would add overtime). Until you could ‘escape’ well above the $65k threshold, basically everyone would be all but obligated to fight for only jobs where they could get paid in these tax-free ways, with other jobs being essentially unpaid except to get you to the $10k threshold.

Given these facts, what is remarkable is how little distortion we see. Why isn’t there vastly more underground economic activity? Why don’t more people stop trying to earn money, or shift between trying to earn the minimum and then waiting to try until they’re ready to earn the maximum, or structuring over time?

My presumption is that this is because the in-kind benefits and conditional benefits are worth a lot less than these charts value them at. Cash is still king. So while the effective rate is still quite high, we don’t actually see 100% marginal tax rates.

If you want more income, Tyler Cowen suggests perhaps you could work more hours? A new estimate says 20% of variance in lifetime earnings is in hours worked, although that seems if anything low, especially given as Tyler points out that working more improves your productivity and human capital.

Tyler Cowen: In the researchers’ model, 90% of the variation in earnings due to hard work comes from a simple desire to work harder. Note again this is an average, so it does not necessarily describe the conditions faced by, say, Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg.

In my experience, vastly more than 20% of my variance in income comes from the number of hours worked and how hard I was working generally. One could draw a distinction between hours worked versus working hard during those hours. I’d guess the bigger factor is how hard I work when I’m working, but the times I’ve succeeded and gotten big payoffs, it wouldn’t have happened at all if I hadn’t consistently worked hard for a lot of hours. The time I wasn’t able to deliver that effort, at Jane Street, it was exactly that failure (and what caused that failure) that largely led to things not working out.

Working hard also applies to influencers. In this job market paper from Kazimier Smith, he finds that the primary driver of success is lots of posting. Sponsored posts grow reach the same as regular posts, which is nice work if you can get it, although this results likely depends on influencers selecting good fits and not overdoing it, and on correlation, where if you are getting sponsorships it is a sign you would otherwise be growing.

The abstract also introduced the question of focus and audience capture. Influencers and other content creators have to worry that if they don’t give the people what they want, they’ll lose out, and I’ve found that writing on certain topics, especially gaming, creates permanent loss of readers. I’d love to see the proper version of that paper too.

Since we’ve now had some major storms, it’s time for another round of reminding everyone that laws against ‘price gouging’ are a lot of why it we so quickly run out of gas and other supplies in emergency situations. Why would you stock extra in case of emergency, if you only can sell for normal prices? Why would you bring in extra during an emergency, if you can only sell for normal prices?

Because presumably, what you value most lies elsewhere.

Dr. Insensitive Jerk: Our relatives in the Florida evacuation zone just told us I-75 is a parking lot, and no gasoline is available.

Do you know why no gasoline is available? Because of price-gouging laws.

Pointing this out provokes a predictable emotional response from adult children. “He should give me gas cheaply! He should store an infinite amount of gasoline so he can fill up all the hoarders, and still have gas left for me, and he should do it for the same price as last week!”

Now when Floridians need gasoline desperately, they can’t buy it at any price, because other Floridians said, “It’s cheap, so I might as well fill the tank.”

People outside Florida with tanker trucks full of gasoline might have considered helping, but instead they said, “I won’t risk it. If I charge enough to make it worth my while, I will be arrested and vilified in the press.”

But at least the Floridians won’t have to lie awake in their flooded houses worrying that somebody made a profit from rescuing them.

Alas, the Bloomberg editorial board will keep on writing correct takes like ‘Price Controls Are a Bipartisan Delusion’ (the post actually downplays the consequences in a few cases, if anything) and we will go on doing it.

I appreciate this attempted reframing, though I doubt it will get through to many:

Maxwell Tabarrok: High prices during emergencies aren’t gouging – they’re bounties for desperately needed goods. Like a sheriff offering a big reward to catch a dangerous criminal, these prices incentivize the entire economy to rush supplies where they’re most needed.

With two major hurricanes in the last couple of weeks, “price gouging” is in the news. In addition to it’s violent name, there are good intuitive reasons to dislike price gouging.

But imagine if you were the sheriff of Ashville, NC, and it was your job to get more gasoline and bring it into town.

You might offer a bounty of $10 a gallon, dead or alive.

That’s a lot more than the usual everyday bounty, but this is an emergency.

Prices aren’t just a transfer between buyer and seller.

They’re also also a signal and incentive to the whole world economy to get more high-priced goods to the high-paying area; they’re a bounty.

The last thing you’d want if you were the sheriff is a cap on the bounty price you’re allowed to set.

High prices on essential goods during an emergency are WANTED posters, sent out across the entire world economy imploring everyone to pitch in and catch the culprit.

The difficulty that many people may have in paying these higher prices is a serious tragedy, and one that can be alleviated through prompt government response e.g by sending relief funds and shipping in supplies. But setting prices lower doesn’t mean everyone can access scarce and expensive essential goods. In an emergency, there simply aren’t enough of them to go around.

Setting low prices might mean the few gallons of gas, bottles of water, or flights that are available are allocated to people who get to them first, or who can wait in line the longest, but it’s not clear that these allocations are more egalitarian.

These allocations leave the central problem unsolved: A criminal is on the loose and a hurricane has made it difficult to get these goods to where they’re needed.

When there’s an emergency and a criminal is on the loose, we want the sheriff to set the bounty high, and catch ‘em quick. High prices during other emergencies work the same way. Let the price-system sheriff do his work!

Scott Sumner points out that customers very much prefer ridesharing services that price gouge and have flexible pricing to taxis that have fixed prices, and very much appreciate being able to get a car on demand at all times. He makes the case that liking price gouging and liking the availability of rides during high demand are two sides of the same coin. The problem is (in addition to ‘there are lots of other differences so we have only weak evidence this is the preference’), people reliably treat those two sides very differently, and this is a common pattern – they’ll love the results, but not the method that gets those results, and pointing out the contradiction often won’t help you.

Chinese VC fundraising and VC-backed company formation has fallen off a cliff, after China decided they were going to do everything they could to make that happen.

Financial Times: Venture capital executives in China painted a bleak picture of the sector to the FT, with one saying: ‘The whole industry has just died before our eyes.’

Bill Gurley: Many in Washington are preoccupied with China. If this article is accurate, the #1 thing we could do to improve US competitiveness, would be to open the door much more broadly & quickly to skilled immigration. Give these amazing entrepreneurs a home on US soil.

It’s important to note these are private VC funds and VC-backed companies only. This is not the picture of all new enterprise in China. There are plenty of new companies.

According to FT, venture capital has died because the Chinese government intentionally killed it. They made clear that you will be closely monitored, your money is not your own and cannot be transferred offshore, your company is not your own, the authorities could actively go after the most successful founders like Jack Ma, that you are to reflect ‘Chinese values’ or else. Venture capital salaries are capped.

What is left of venture is often suing companies to get their money back, so the government doesn’t accuse them of not trying to get the money back on behalf of the government. New founders are required to put their house and car on the line.

The advocates of Venture Capital and the related startup ecosystem present it as the lifeblood of economic dynamism, innovation and technological progress. If they are correct about that, then this is a fatal blow.

Often we hear talk about ‘beating China,’ along with warnings of how we will ‘lose to China’ if we do some particular thing that might interfere with venture capital or the tech sector. Yet here we have China doing something ten or a hundred or a thousand times worse than any such proposals. Yet I don’t expect less worrying about China?

One perspective listing what 2% compounding annual economic growth feels like once you get to your 40s. It is remarkably similar to my experience – I look around and realize that the stuff I use and value most is vastly better and cheaper, life in many ways vastly better, things I used to spend lots of time on now at one’s fingertips for free or almost free.

A new paper asks why inflation is costly to workers.

We argue that workers must take costly actions (“conflict”) to have nominal wages catch up with inflation, meaning there are welfare costs even if real wages do not fall as inflation rises.

We study a menu-cost style model, where workers choose whether to engage in conflict with employers to secure a wage increase.

…

We conduct a survey showing that workers are willing to sacrifice 1.75% of their wages to avoid conflict. Calibrating the model to the survey data, the aggregate costs of inflation incorporating conflict more than double the costs of inflation via falling real wages alone.

Matt Bruenig rolls his eyes and suggests that a union could take care of that conflict for the workers.

Matt Bruenig: Also worth considering the degree to which “conflict costs” constitute another of the frictions that prevent job-switching (people don’t like upsetting their boss/colleagues), which again points towards collective bargaining as important and a limitation of anti-monopsony.

I got a job once that I left after 6 weeks because I got an unexpected offer that paid about $20k more per year and boy did I have to hear what a piece of shit I was from the person who hired me in the first job. It’s as if they had never even read the textbook.

Matt Yglesias: This resonates with me as I ask myself why I re-upped my Bloomberg column contract at the same nominal salary without even attempting to negotiate for a higher fee.

Except I have seen unions, and whatever else you think of unions they do not exactly minimize such conflicts, instead frequently leading to deadweight losses including strikes. And I have no doubt that inflation substantially increases the average costs of such conflicts.

The reason a worker would pay to avoid conflict with the boss is partly it is unpleasant, partly The Fear, and partly because it can result in anything from turning the work situation miserable up through a full ‘you’re fired,’ or in the union case a strike. At minimum, it risks burning a bunch of goodwill.

Also Matt should realize that when you take a new job after six weeks and quit, you have imposed rather substantial costs on your old employer. During those six weeks, you were probably a highly unproductive employee. They spent a lot of time hiring you, training you, getting you up to speed, and then you burned all that effort and left them in another lurch.

Of course they are going to be mad, although the bigger the gap in offers the less mad they should be. We’ve decided that the employee doesn’t strictly owe the employer anything here, it’s a risk the employer has to take, but at minimum they owe them the right to be pissed off – you screwed them, whether or not it was right to do that.

Another way to look at this is that the decline in real wages is a cost, which then often means other costs get imposed, including deadweight losses like switching jobs or threatening to do so, in order to fix it, but that as is often the case those new costs are a substantial portion of the original loss.

There are also the actual real losses. This is especially acute in situations that involve wages being sticky downwards, or someone is otherwise ‘above market’ or above their negotiating leverage. For example, when I joined [company], I was given a generous monthly salary. I stayed for years, but that number was never adjusted for inflation, because it was high and I needed my negotiating points for other things – I didn’t want to burn them on a COLA or anything.

Often salary negotiations happen at times of high worker leverage, when they have another offer or are being hired or had just proven their value or what not. Having to then renegotiate that periodically is at minimum a lot of stress.

As one commenter noted, sufficiently high inflation can actually be better here. If there’s 2% inflation a year, then you’re tempted to sit back and accept it. If it’s 7%, then you have a fairly straightforward argument you need an adjustment.

Vincent Geloso points out that federal any income tax data before 1943 is essentially worthless if you are looking at distributional effects. The IRS was known not to bother auditing, inspecting or challenging tax returns of less than $5k, which was 91% of them in 1921. It is a reasonable policy to focus auditing and checking on wealthier taxpayers.

But this policy was sufficiently known and reliable that it resulted in absolutely massive tax evasion, as in 95% of people earning under $2,000 a year flat out not bothering to file. Needless to say, at that point you might as well set the tax for such people to $0 and tell them they don’t need to file.

When considering insurance costs as a signal, how does one differentiate what is risky versus what are things only people who are bad risks would choose to do?

John Horton: If you listen, insurance companies are giving you solid, data-driven advice about stuff not to do or buy—don’t own a pit bull, don’t have a trampoline, don’t under-water cave dive, don’t own a “cyber” truck…

what’s kind of nuts is that when instead of just quoting you a higher price, they explicitly just will not cover it. To me, that suggests they think adverse selection is a problem. It’s not *justthat pit-bulls are natural toddler-eaters, they think you’re a reckless idiot and a higher price just increases the average idiocy of the customers, with predictable results

Gwern: Or they don’t have enough data.

The problem is, insurance companies only need correlates. So none of that is good advice about stuff you should do – unless you are planning to starting to transition to a woman because of lower insurance rates for women on many things…?

Robert Parham: Upon inspection, it seems like a externality issue. The cybertruck is so tough that any accident with it leaves the truck unscathed while totalling the other car. The Insurance company is liable for the totalled car, hence the decision.

Insurance is indeed pretty great for things like internalizing that your cybertruck would be very bad for any other car that got into an accident with it. The problem is that when you price out trampoline insurance, a lot of this is that people who tend to buy trampolines are reckless, so you don’t know how much you should avoid owning one.

I even wonder if ‘arbitrary’ price differentials would be good. If you charge less for insurance on houses that are painted orange than those painted green, and someone still wants to insure their green house, well, do they sound like responsible people?

As the tech job market continues to struggle, I’m seeing more threads like this asking if it’s time to reevaluate career and college plans based around being a software engineer. My answer continues to be no. Learning how to code and build things is still a high expectancy path.

Work from home allows workers to be paid for the 10 hours they actually work, without having to semi-waste the other 30. What is often valuable is the ability to suddenly work 60-80 hours a week when it matters, or that one meeting or day when you’re badly needed, and it’s fine to work 10 hours (or essentially 0 hours) most other weeks, and the payment is so you’re on standby.

Detty: The most surreal aspect of the WFH vs. in-office debate is how it’s widely acknowledged that hundreds of millions of people do very little all day every day and yet the economy continues to just churn & those who don’t have the magic piece of paper work very hard for very little.

Seth Largo: Lots of corporations and institutions are so wealthy that it makes sense to pay someone a full time salary for 10 hours of work per week, because those 10 hours really do help keep the machine running, and no one’s gonna do it for 10 hours of pay.

Lindy Manager: Also managers need people available who can activate for bursts when needed who have all the context and information to create or present something of sufficient quality on short notice for a client or executive.

Seth Largo: Don Draper knew this.

ib: Yep. A lot of corporate salaries are effectively retainers.

Always Adblock: Yes. And to keep their institutional knowledge. And to keep them away from competitors.

Had this section in reserve for a post that likely will never come together on its own, so figured this was a good time for it.

Paper concludes minimum wage increases drive increased homelessness due to disemployment effects and rental price increases, and dismisses migration as a potential cause. I mean, yes, obviously, on the main result.

A better question is, what does the minimum wage do to rental costs? The minimum wage does successfully cause some work to become higher paid. Most such workers will not be homeowners. It is entirely plausible that landlords could capture a large portion of these gains via higher rents for low-quality housing, perhaps all of it. In which case, what was the point?

Restaurants in Milan used to be forced to be distant from each other, then they stopped requiring that, resulting in agglomeration that caused diverging amenities in different neighborhoods, and increased product differentiation. Tyler Cowen notes ‘I am myself repeatedly surprised how much the mere location of a restaurant can predict its quality.’

I would think of this less as returns to agglomeration and more as it being costly to force restaurants to locate in uneconomical locations, and to effectively undersupply some areas, leading to lack of competition and variety there, while oversupplying others. By creating product differentiation in location, this reduces their incentive to otherwise differentiate or seek higher quality.

The U.S. college wage premium doubles over the life cycle, from 27 percent at age 25 to 60 percent at age 55. Using a panel survey of workers followed through age 60, I show that growth in the college wage premium is primarily explained by occupational sorting. Shortly after graduating, workers with college degrees shift into professional, nonroutine occupations with much greater returns to tenure.

Nearly 90 percent of life cycle wage growth occurs within rather than between jobs. To understand these patterns, I develop a model of human capital investment where workers differ in learning ability and jobs vary in complexity. Faster learners complete more education and sort into complex jobs with greater returns to investment. College acts as a gateway to professional occupations, which offer more opportunity for wage growth through on-the-job learning.

Tyler Cowen suggests this causes problems for the signaling model of education. I disagree, and see this result as overdetermined.

-

Path dependence. Those who go to college then enter professions and careers that allow for such wage growth, from a combination of skills development and social and reputational accumulation. Thus, whatever mix of signaling, correlation and education is causing these other paths, the paths are opened by college, and this has a predictable effect over time.

-

In particular: Gatekeeping. I don’t buy that future employers will no longer care if you went to college. Many high paying jobs will be difficult or impossible to get without a degree, and the degree helps justify paying someone more, since pay is largely about affirming social status. Gatekeeping thus keeps such people increasingly down over time as results compound, and also discourages investment. Why develop human capital that no one will pay for?

-

Correlational. If you go to college, this is a revealed preference for longer time horizons and longer term investment, including the capacity and capability to do it. It makes sense that such folks would continue to invest in human capital growth over time relative to others.

-

In particular: Signaling. Alas, those more willing to invest more time and resources in signaling likely get better compensated over time. Also college plausibly teaches you how to signal.

-

Catching up. If you take a job rather than go to college, you are going to start out with several years of practical experience, which gives you a temporary advantage that fades over time. College students first entering the workforce are famously out of touch and useless, lacking practical skills, and are coming from a sheltered academic world with unproductive norms. Over time, you get over it.

Tyler Cowen put the rooftops tag on this study from Andreas Ek (gated):

This paper estimates differences in human capital as country-of-origin specific labor productivity terms, in firm production functions, making it immune to wage discrimination concerns. After accounting for wage and experience, estimated human capital varies by a factor of around 3 between the 90th and 10th percentile. When I investigate which country-of-origin characteristics correlate most closely with human capital, cultural values are the only robust predictor. This relationship persists among children of migrants. Consistent with a plausible cultural mechanism, individuals whose origin place a high value on autonomy hold a comparative advantage in positions characterized by a low degree of routinization.

I don’t understand why we want to be shouting this from the rooftops. These types of correlations are the kind that very much do not imply causation, the whole thing is doubtless confounded to hell and back and depends on a bunch of free variables. Autonomy is one of those values that maps reasonably closely with ‘The West’ and so does the level of human capital.

The core claim is that if your culture values autonomy, then you are better suited to a less routine production activity and hold comparative advantage there. Which is a case where I am confused why we needed a study or mathematical model. How could that have been false? Less routine is not the same as more autonomous but the correlation is going to be very high. People with cultural value X hold comparative advantage in activities that embody X, paper at conference?

War Discourse and the Cross Section of Expected Stock Returns finds that the paper’s model of what war tail risks should be worth does not match the market’s past evaluation of what war tail risks should be worth, and decides it is the market that is wrong. I am highly open the market mispricing things like this, especially in response to media salience, but I’m even more open to the academics being wrong.

Paper claims that we are gaining 0.5% per year in terms of how much welfare we get from across a variety of categories from increased product specialization and variety. Households increasingly spend funds on specialized products that exactly fit their preferences, with the increased variety driving the divergence in consumption.

This is also evidence we are richer. Increased product variety requires people able to consume enough, and pay enough extra for quirky preferences, to justify greater product variety. This represents a real welfare gain. However, instead of making people feel less constrained and wealthier, it puts strain on budgets and competes with and potentially puts additional strain on raising families rather than making it cheaper to raise one.

I very much appreciate the product variety, but increasingly I think we need to consider three different measures of wealth:

-

The welfare value of the experience of the items in a typical consumption basket.

-

The combined welfare value including goods that remain unpriced.

-

The difficulty in purchasing the typical consumption basket, and what affordances that leaves for life goals especially retirement, marriage and children.

Or: The Iron Law of Wages proposes that real wages tend toward the minimum to sustain the life of the worker. So we can measure four things.

-

The minimum real wages required to sustain the life of the worker.

-

The welfare value of that minimum consumption basket.

-

The surplus available after that to the typical worker and what that buys them.

-

What else is available that is not priced.

When we either effectively mandate additional consumption, such as purchasing additional safety, health care, residence size, education or other product features, or our culture effectively demands such purchases, or the cheaper alternatives stop being available, what happens?

We do increase the welfare value of the minimum basket. We also raise the cost of that basket, which reduces everyone’s surplus.

What happens when things that people value, like community and friendship and the ability to raise children without being terrified of outside intervention, and opportunities to find a good life partner, are degraded?

Life gets worse without it showing up in the productivity statistics or in real wages.

The current crisis and confusion could be thought of as:

-

The value of the minimum consumption basket is going up a lot.

-

The cost of the minimum consumption basket is going up less than that.

-

Real wages are going up, but less than the cost of the basket, so the surplus available after purchasing the basket is also declining.

-

Key other goods and options are taken away, like those mentioned above.

-

Economists say ‘workers are better off,’ and in many ways they are.

-

People say ‘but I have little surplus and do not see how to meet my life goals and I have no hope and my life experience is getting worse.’

Paper explores the impact of the 2010 dissolution of personal income tax reciprocity between Minnesota and Wisconsin. This looks like it on average raised effective taxes on work across state lines by about 8% of remaining net income. This resulted in a decline in quantity of cross-border commuters between 3% and 5%, with the largest impact on low and young earners. My hunch is that the impact size is so low primarily because of inertia, switching costs and lack of understanding of the costs. Whereas jobs that don’t pay as well, and those of the young, are less sticky. It would be shocking if an 8% tax had this small an effect at equilibrium.

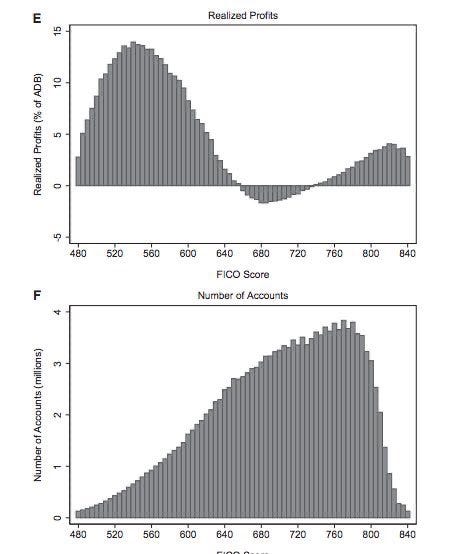

Paper estimates that the CARD Act, which limits credit card interest charges and fees, saved consumers $11.9 billion per year, lowering borrowing costs by 1.6% overall and by 5.3% for those with FICO below 660. What is odd is they also find no corresponding decrease in available credit, despite this making offering credit less profitable. There is no free lunch. A potential story is that credit cards adjusted their other costs and benefits, or the counterfactual here is not well established and there would have been growth in credit otherwise, or the good version is that the whole enterprise is so profitable and useful that the banks ate the reduced profits.

There’s also the strange graph below, which requires explaining. Patrick McKenzie points out that the part of the FICO curve where offering credit cards is unprofitable is still a good place to do business, because those in the unprofitable range are unlikely to stay there so long and their business will remain somewhat sticky as they move.

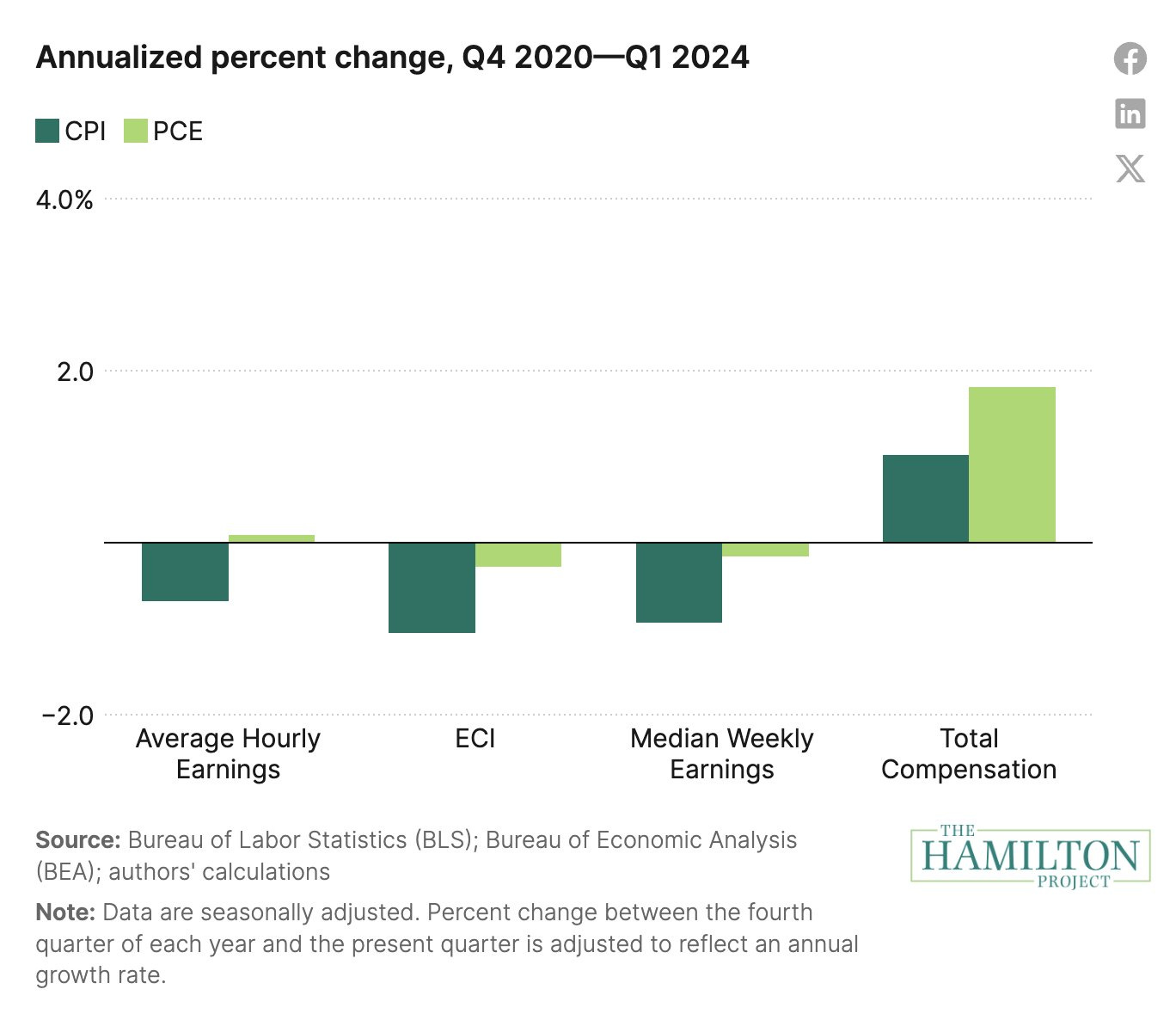

Has real median income gone up under Biden? This clart implies that it perhaps hasn’t, even if weird timing is involved, and that this explains a lot. Yes, pay has increased since 2019, and increased since 2022, but the question people often effectively ask is since the end of 2020.

‘Total compensation’ is cool but what people look at is the actual money.