A Croatian energy company has discovered an underwater lake of superheated water that could supply the country’s far north with clean geothermal electricity.

The find was the result of a two-year study by state-run power company Bukotermal that sought to find suitable sites for the exploitation of the energy source, generated by heat from the Earth’s core.

The research verified the presence of a geothermal water source at Lunjkovec – Kutnjak field, located in the Varazdin County, close to the border with Hungary. The underground lake, located at a depth of 2.4 kilometres, has an average temperature of 142.03 degrees Celsius.

Varazdin County confirmed on Tuesday that the site meets all the requirements for the construction of a 16MW geothermal power plant. That’s enough energy to supply tens of thousands of homes.

To date, over €2.5mn has been invested in the project. However, according to Alen Pozgaj, CEO of Bukotermal, the total cost to build the plant would be around €50mn.

The news comes just days after the Croatian Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development awarded five licences for the exploration of geothermal waters to firms from Croatia, the United Kingdom, and Turkey.

The tender was issued by the Croatian Hydrocarbon Agency, has a value of over €40mn, and concerns five areas in the region’s north and northeast that already have existing wells, a legacy from retired oil and gas operations. Tapping these wells means companies don’t have to drill new ones, cutting the risk and costs for investors, said the Ministry.

Croatia has been ramping up efforts to exploit its extensive geothermal resources in recent years as it looks to wean itself off imported fossil fuels. The Balkan state, as well as its neighbours Hungary and Slovenia, sits on a geologically active area known as the Pannonian region. In this area, the water is boiling a little more than a mile down and gets hotter the deeper a well is drilled.

“Based on an extensive database, we know that the Pannonian area has perfect conditions for development of geothermal business, with geothermal gradient 60% higher than the European average,” Marijan Krpan, the head of the Croatian Hydrocarbon Agency’s (CHA) managing board, told Reuters.

In the EU, Italy is by far the largest electricity producer from geothermal energy with some 915MW capacity, followed by Germany (38MW) and Portugal (30MW). While Croatia’s installed capacity is much lower, but the government has committed hot water pools have the potential to supply one-third of the country with clean electricity if harnessed.

There are already projects underway in the country that pump hot water from under the ground to heat entire towns, and farmers are using the technology to warm their greenhouses. The country’s first geothermal power plant was put into operation in 2019.

The Velika Ciglena power plant has 10MW of installed capacity, which corresponds to the average consumption of 29,000 Croatian households. That’s equivalent to about the electricity generated by about 94 football fields of solar panels, on a plot of land that is less than a tenth that size.

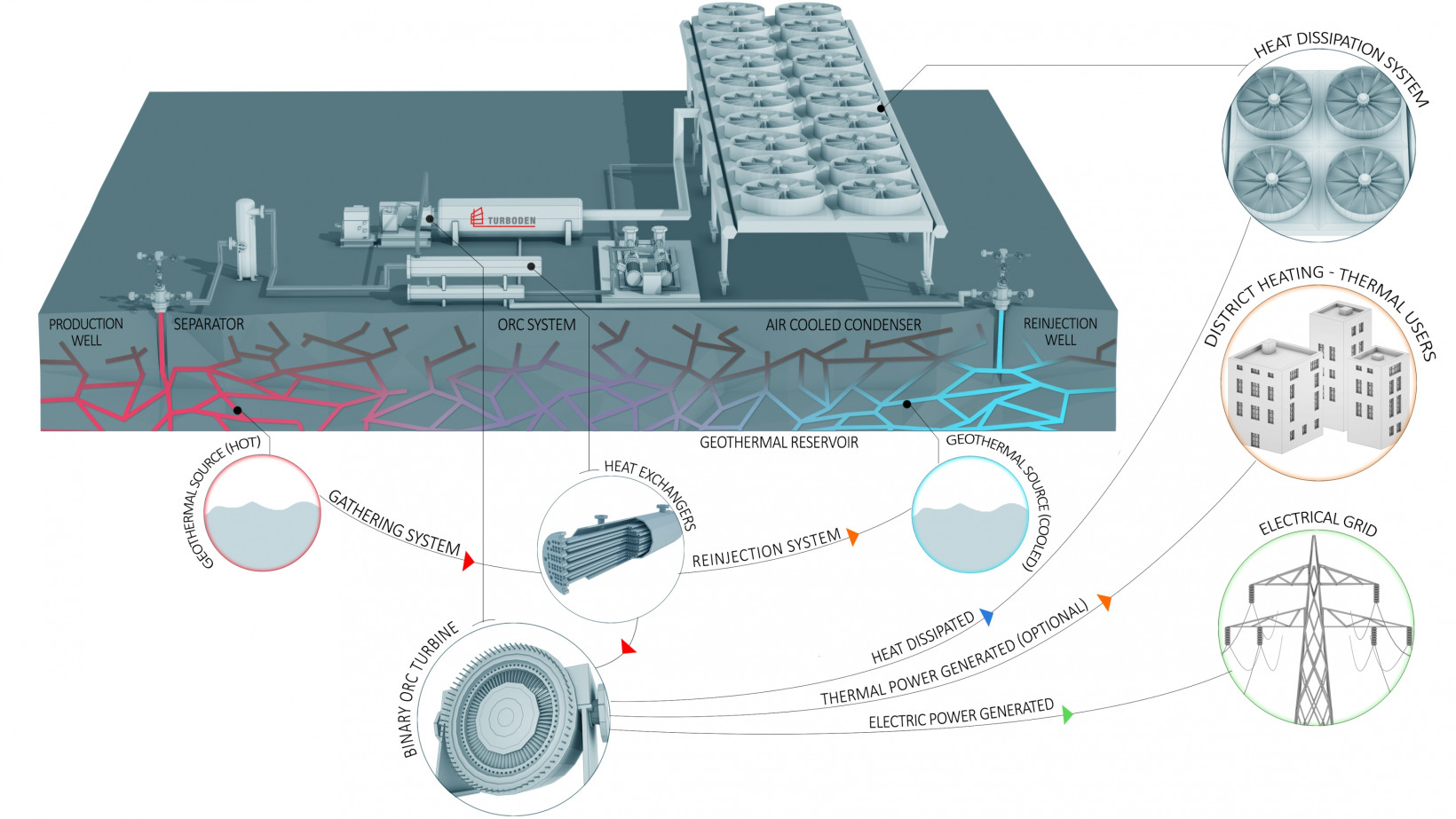

The facility’s core technology was produced by Italy’s Truboden. The plant pumps hot water that has been heated by the energy of the earth’s core to the surface through a pipeline drilled two kilometres into the ground. The heat is used to make steam that spins turbines, generating electricity. Then the cooled water is pumped back down into the ground.

For backers of the technology, geothermal energy presents a source of 24/7 power that is more consistent than wind and solar, and less vulnerable to weather extremes — like hydropower dams that are sometimes forced to shut off entirely during periods of drought.

But there is wide variability from site to site, drilling wells is expensive, and often it’s impossible to know in advance whether a drill hole will yield good enough water. That can scare off investors. Using existing wells previously used for oil and gas exploration is one solution to cost-cutting, which is exactly the approach Croatia is currently taking.

For now, Bukotermal has a six-month timeframe to propose how it will exploit the newly discovered geothermal pool. The company plans to construct one or more geothermal power plants and heat utilisation facilities at the site, with construction expected to start within two years time.