Related: On the 2nd CWT with Jonathan Haidt, The Kids are Not Okay, Full Access to Smartphones is Not Good For Children

It’s rough out there. In this post, I’ll cover the latest arguments that smartphones should be banned in schools, including simply because the notifications are too distracting (and if you don’t care much about that, why are the kids in school at all?), problems with kids on social media including many negative interactions, and also the new phenomenon called sextortion.

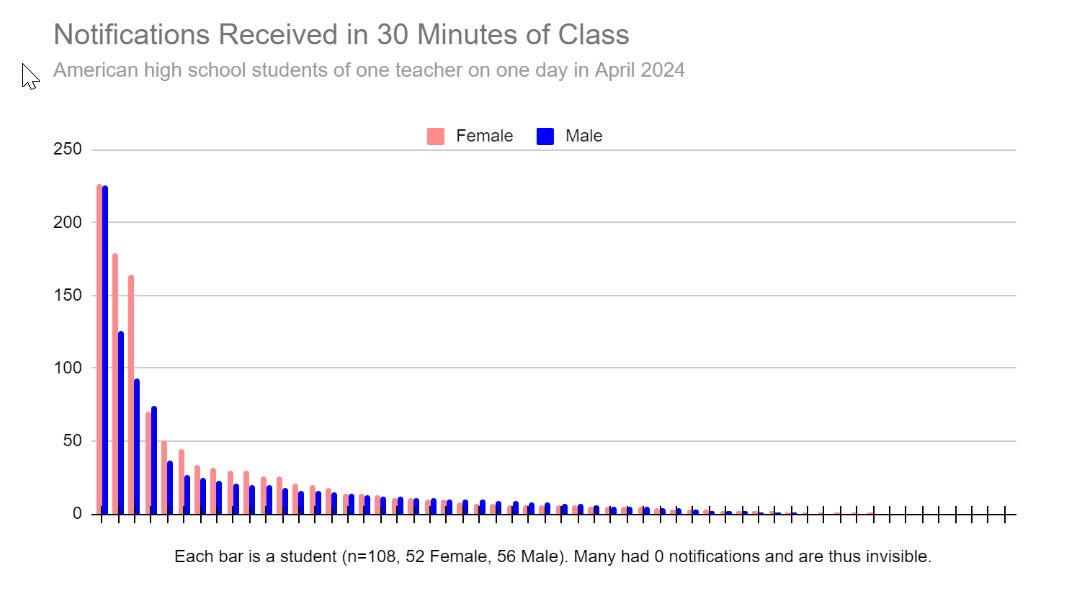

Tanagra Beast reruns the experiment of having a class tally their phone notifications. The results were highly compatible with the original experiment.

The tail, it was long.

Ah! So right away we can see a textbook long-tailed distribution. The top 20% of recipients accounted for 75% of all received notifications, and the bottom 20% for basically zero. We can also see that girls are more likely to be in that top tier, but they aren’t exactly crushing the boys.

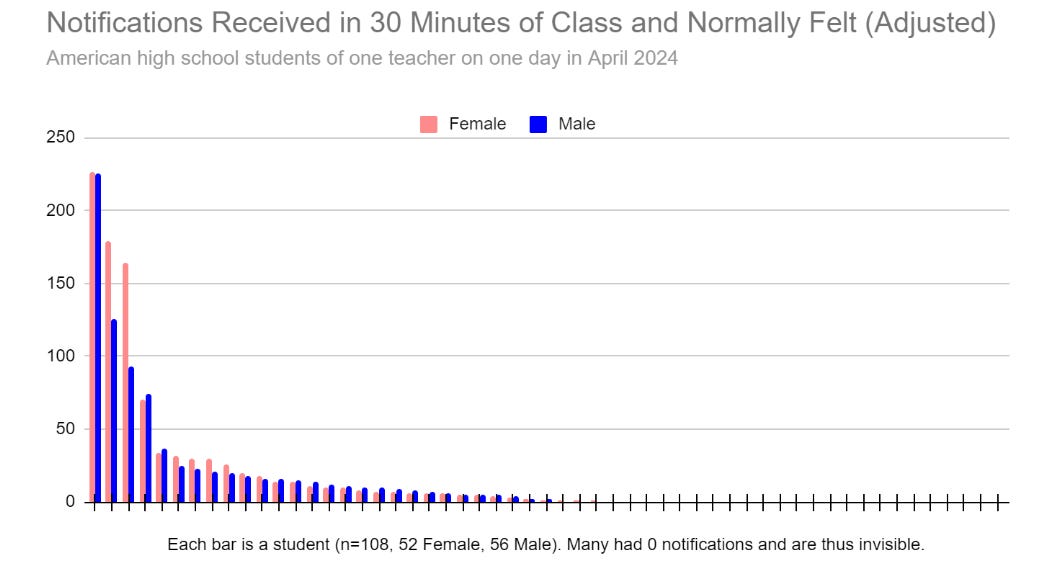

What if you asked only about notifications that would actually distract?

There was even more concentration at the top. The more notifications you got, the more likely you were to be distracted by each one.

Here are some more highlights.

Which apps dominate? Instagram and Snapchat were nearly tied, and together accounted for 46% of all notifications. With vanilla text messages accounting for an additional 35%, we can comfortably say that social communications account for the great bulk of all in-class notifications.

There was little significant gender difference in the app data, with two minor apps accounting for the bulk of the variation: Ring (doorbell and house cameras) and Life 360 (friend/family location tracker), each of which sent several notifications to a few girls. (“Yeah,” said girls during our debriefing sessions, “girls are stalkers.” Other girls nodded in agreement.)

Notifications from Discord, Twitch, or other gaming-centric services were almost exclusively received by males, but there weren’t enough of these to pop out in the data.

The two top recipients, with their rate of 450 notifications per hour (!), or about one every eight seconds, had interesting stories to tell. One of these students had a job after school, and about half their messages (but only half) were work-related. The other was part of a large group chat, and additionally had a friend at home sick who was peltering them with a continuous rant about everything and nothing, three words at time.

Some students who receive very large numbers of notifications use settings to differentiate them by vibration patterns, and tell me that they “notice” some vibrations much more than others.

Official school business is a significant contributor to student notification loads. At least 4% of all notifications were directly attributable to school apps, and I would guess the indirect total (through standard texts, for example) might be closer to 10-15%. For students who get very few notifications, 30-50% of their notifications might be school-related. Our school’s gradebook app is the biggest offender, in part because it’s poorly configured and sends way more notifications than anyone wants.

Is our school unusually good or bad when it comes to phones? By a vote of 23 to 7, students who had been enrolled in another school during the last four years said our school was better than their previous school at keeping phones suppressed.

There’s still obvious room for improvement, though. I asked my students to imagine that, at the start of the hour, they had sent messages inviting a reply to 5 different friends elsewhere on our campus. How many would they expect to have replied before the end of the hour? The answer I consistently got was 4, and that this almost entirely depended on the phone-strictness of the teacher whose class each friend was in. (I’m on the list of phone-strict teachers, it seems. Phew!)

I asked students if they would want to press a magic button that would permanently delete all social media and messaging apps from the phones of their friend groups if nobody knew it was them. I got only a couple takers. There was more (but far from majority) enthusiasm for deleting all such apps from the whole world. I suspect rates would have been higher if I had asked this as an anonymous written question, but probably not much higher.

I asked if they thought education would be improved on campus if phones were forcibly locked away for the duration of the school day. Only one student gave me so much as an affirmative nod! Among students, the consensus was that kids generally tune into school at the level they care to, and that a phone doesn’t change that. A disinterested student without a phone will just tune out in some other way.

As I’ve mentioned before, I find phones distracting when doing non-internet activities even when there are zero notifications. Merely having the option to look is a tax on my attention. And as Gwern notes in the comments, the fact that a substantial minority of students would want to nuke messaging apps from orbit is more a case of ‘that is a lot’ rather than ‘that is only a minority.’ Messaging apps provide obvious huge upside in normal situations outside school, so a lot of kids must see big downsides.

New York City may ban phones in all public schools.

Julian Shen-Berro and Amy Zimmer: [NYC schools chancellor] Banks previously said he’s been talking with “hundreds” of principals, and they have overwhelmingly told him they’d like a citywide policy banning phones.

…

“We know [students] need to be in communication with their parents after school,” Banks said, “and if there’s something going on during the day, parents should just call the school the way they always did before we ever had cell phones.”

He previously had said we weren’t there yet, largely because bans are hard to enforce. To me that continues to make no sense. You can absolutely enforce it. In fact, it seems much easier to me to enforce a total ban on cell phones via sealed pouches than it is to enforce reasonable use of those phones while leaving them within reach.

WSJ reports many parents being the main barriers to banning phones in schools. Some strongly support bans, and the evidence here once again is strongly that bans work to improve matters, but other parents object because they demand direct access to their children at all times.

As always, school shootings are brought up, despite this worry being statistically crazy, and also that cell phone use during a school shooting is thought to be actively dangerous because it risks giving away one’s location. I can’t even.

The more reasonable objections are outside emergencies and scheduling issues, which is something, but wow is that a cart before horse situation. Also obviously there are vastly less disruptive ways to solve those problems. Mostly, I think staying in constant contact at that age is actively terrible for the students. You do want to be able to reach each other in an emergency, but there should be friction involved.

If a few parents pull their kids out in protest, let them. Others who support the policy can choose to transfer in. If my kids were at a school where everyone was on their phones all the time, and I had a viable alternative where phones were banned, I would not hesitate. At minimum we can let the market decide.

It can be done. Here is a story of one Connecticut middle school banning phones. All six middle schools in Providence use them, as do two high schools there. Teachers say sealing phones in pouches has been transformative.

Tyler Cowen reports on a new paper on the Norwegian ban of smartphones in middle schools. Here is the abstract:

How smartphone usage affects well-being and learning among children and adolescents is a concern for schools, parents, and policymakers.

Combining detailed administrative data with survey data on middle schools’ smartphone policies, together with an event-study design, I show that banning smartphones significantly decreases the health care take-up for psychological symptoms and diseases among girls. Post-ban bullying among both genders decreases.

Additionally, girls’ GPA improves, and their likelihood of attending an academic high school track increases. These effects are larger for girls from low socio-economic backgrounds.

Hence, banning smartphones from school could be a low-cost policy tool to improve student outcomes.

Tyler does his best to frame this effect as disappointing and Twitter summaries saying otherwise as misleading (he does not link to them), although he admits he is surprised that bullying fell by 0.39 SDs for boys and 0.42 SDs for girls. Grades did not improve much, only 0.08 SDs, of course we do not know how much this reflects the real changes in learning. Also as one commenter points out, phones are good for cheating.

A plausible explanation for why the math change was 0.22 SDs is that this was based on standardized tests, where the teachers aren’t adjusting the curve for the changes. Or it could be that it is helpful to not always have a calculator in your pocket.

I would also note his second point: ‘The girls consult less with mental health-related professionals, with visits falling by 0.22 on average to their GPs, falling by 2-3 visits to specialist care.’ That is a 29% decline in GP visits, and a 60% decline in specialist visits. That is a gigantic effect. Some of it is ‘phones cause kids to seek help more’ but at today’s margins I am fine with that, and this likely represents a large improvement in mental health.

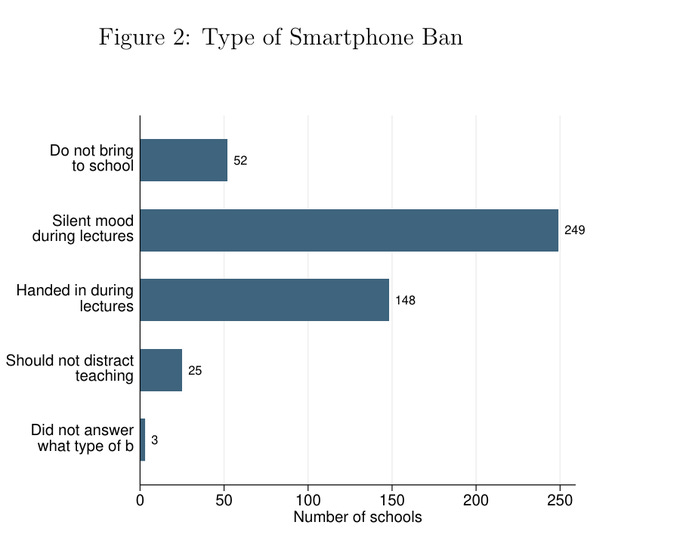

I also note that the paper shows that the effects are largest for schools that do a full ban, those that let phones remain on silent see smaller impacts. As the author points out, this is likely because a phone nearby is a constant distraction even when you ultimately ignore it. Silent mode was a little over half the sample (see Figure 2). So the statistics understate the effect size of a full ban.

This did not take phones away outside of school, so it is not a measure of full phone impact, only the marginal impact of phones in schools, and mostly only of making the phones go on silent.

Jay Van Bavel summarizes this way:

Jay Van Bavel, PhD: Banning #smartphones in over 400 schools led to:

-decreased psychological symptoms among girls by 29%

-decreased bullying by boys and girls by 43%

-increased GPA among girls by .08 SDs

Effects were larger for girls from low SES families

We should keep smartphones out of schools. This technology is a collective trap–Users are compelled to use it, even if they hate it.

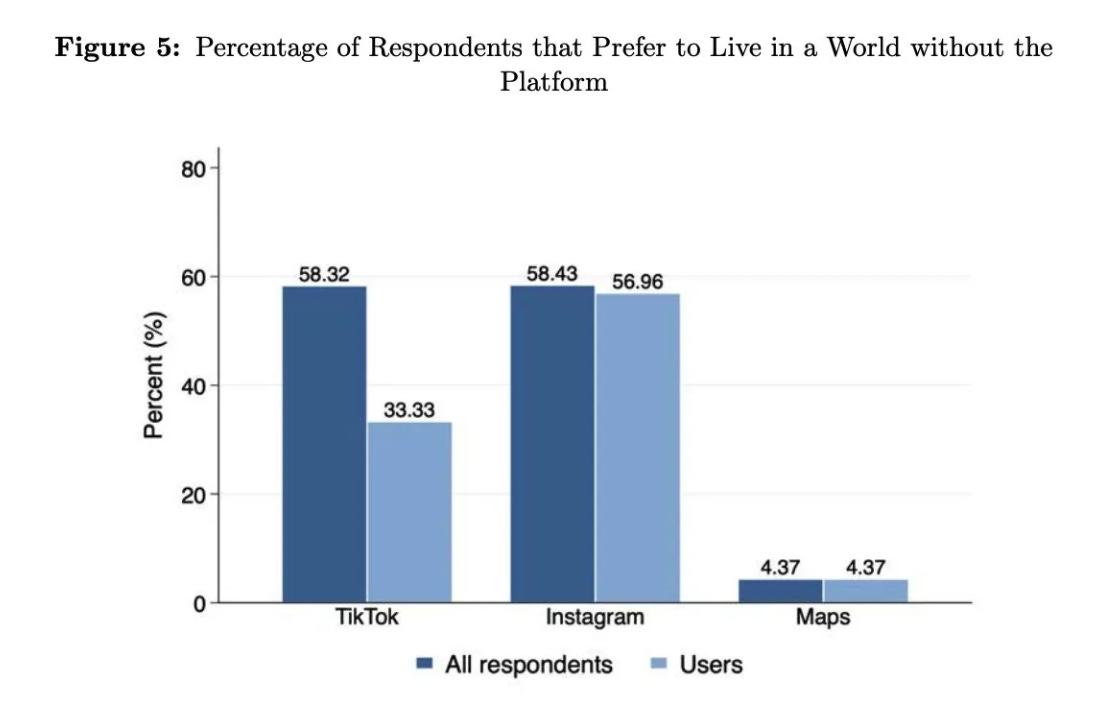

Most people would prefer a world without TikTok or Instagram: Nearly 60% of Instagram users wish the platform wasn’t invented. [link is to post discussing a successful no-ban pilot school program, and various social media issues]

If you take the results at face value, despite many of the ‘bans’ only being partial, don’t you still have to ban phones?

Tyler did not see it that way. He followed up noting that the bans were often not so strict, but claiming that the strict bans had only modest effect relative to the less strict bans. I don’t understand this interpretation of the data, or this perspective.

Consider the opposite situation. Suppose you were considering introducing a new device into schools, and it had all the opposite effects. People would consider you monstrous and insane for even raising the question.

Also I am happy to trust this kind of very straightforward anecdata:

John Arnold: Was walking through a random high school recently and was shocked by the number of kids with a phone in their lap playing games or scrolling and/or wearing headphones during a lesson. Made me very partial to ‘lock phones in pouch’ policies.

If kids constantly being on phones during class is not hurting academic achievement, then that tells you the whole ‘send kids to school’ thing is unnecessary, and you should disband the whole thing.

That is my actual position. Either ban phones in schools, or ban the schools.

California Governor Newsom calls for all schools to go phone free.

Governor Newsom: The evidence is clear: reducing phone-use in classrooms promote concentration, academic success & social & emotional development.

We’re calling on California schools to act now to restrict smartphone use in classrooms. Let’s do what’s best for our youth.

…

In 2019, Governor Newsom signed AB 272 (Muratsuchi) into law, which grants school districts the authority to regulate the use of smartphones during school hours. Building on that legislation, he is currently working with the California Legislature to further limit student smartphone use on campuses. In June, the Governor announced efforts to restrict the use of smartphones during the school day.

…

Leveraging the tools of this law, I urge every school district to act now to restrict smartphone use on campus as we begin the new academic year. The evidence is clear: reducing phone use in class leads to improved concentration, better academic outcomes, and enhanced social interactions.

You know what I’ve never heard? Someone who actually observed teenage girls using social media, and thought ‘yep this seems fine, I’ve updated towards not banning this.’

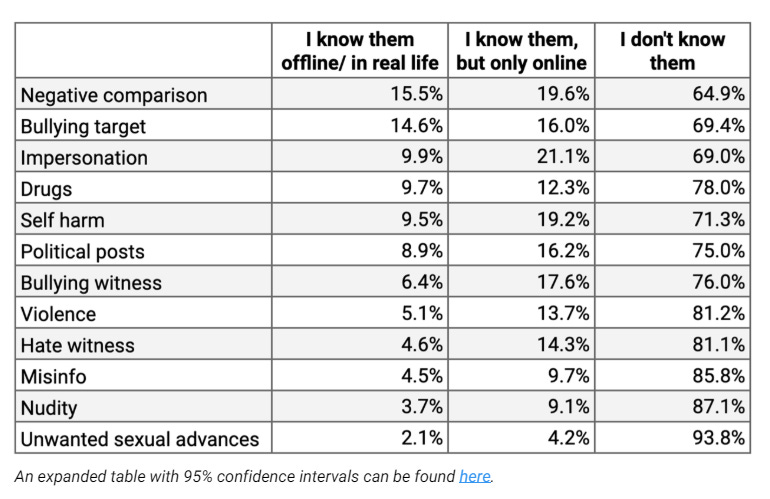

In a given week, 13% of users of Instagram between 13-15 said they had received unwanted sexual advances. 13% had seen ‘any violent, bloody or disturbing image’ which tells me nothing disturbs our kids anymore, and 19% saw ‘nudity or sexual images’ that they did not want to see.

Jon Haidt and Arturo Bejar demand that something (more) must be done. A lot is already being done to get the numbers this contained.

Arturo Bejar: My daughter and her friends—who were just 14—faced repeated unwanted sexual advances, misogynistic comments (comments on her body or ridiculing her interests because she is a woman), and harassment on these products. This has been profoundly distressing to them and to me.

Also distressing: the company did nothing to help my daughter or her friends. My daughter tried reporting unwanted contacts using the reporting tools, and when I asked her how many times she received help after asking, her response was, ‘Not once.’

What would help look like? Would you even know if you were helped? Meta’s own AI believes that she should damn well hear back, and this was a failure of the system.

I was curious to see this broken down by source, so I looked at the original survey from 2021, and there is data.

We also see that about half of those who asked for support felt at least ‘somewhat’ supported. And that all problems including unwanted advances are similarly common for the 13-15 group as the other groups up to age 26, with males reporting unwanted advances more often than females in all age groups, whereas females got more unwanted comparisons.

This all happened back in 2021, before generative AI.

With Llama-3 and also vision models now available to Meta, it seems like we should be able to dramatically improve the situation. Many of these things have no reason to appear. So it seems fairly trivial to have an AI check to see if incoming messages or images from strangers contain some of the various things above, and if so then display a warning or silently censor the message, at least for underage users.

Things like political posts or ‘misinfo’ are trickier. There are obvious issues with letting an LLM or even a person decide what counts here and making censorship decisions. But also there is a reason the post does not talk about those issues. They are not where most of the damage lies.

The general consensus continues to be that if you look at what kids, especially teenage girls, are actually doing with social media, you’ll probably be horrified.

Zac Hill: After spending the weekend with a trio of normal, well-adjusted 14 y/o girls (courtesy of my goddaughter), never have I rolled harder for the “Ban Social Media For Teens Like Yesterday” posse.

Via this post by Jay Van Bavel, we are reminded of the ‘we would pay to get rid of social media, in particular TikTok and Instragram’ result.

This graph is pretty weird, right? Why would using Instagram not correlate with wishing the app did not exist? Whereas TikTok’s graph here makes sense (note that the dark blue bar is everyone, not only non-users, so if ~33% of Americans use TikTok then ~70% of non-users want it to not exist).

For Instagram, I suppose as a non-user I can be indifferent, whereas many users feel like they have to be on it?

For Maps, I assume almost everyone uses it, so the two samples are the same people?

There is a very big downside to limiting screen time.

Jawwwn: 🔮 $PLTR co-founder Peter Thiel on screen time for kids 📺:

“If you ask the executives in those companies, how much screen time do they let their kids use, and there’s probably an interesting critique one could make.

Andrew: What do you do?

Thiel: “An hour and a half a week.”

Gallabytes: Absolutely insane to me to see hackers grow up and try to raise their kids in a way that’s incompatible with becoming hackers.

The hard problem is, how do you differentially get the screen time you want?

At some point yes you want to impose a hard cap, but if I noticed my children doing hacking things, writing programs, messing with hardware, or playing games in a way that involved deliberate practice, or otherwise making good use, I would be totally fine with that up to many hours per day. The things they would naturally do with the screens? Largely not so much.

SF Chronicle: Among girls 15 and younger, 45% of those from abusive and disturbed families use social media frequently, compared to just 28% from healthy families.

Younger girls who frequently use social media are less likely to attempt suicide or harm themselves than those who don’t use social media.

…

The CDC survey shows that 5 in 6 cyberbullied teens are also emotionally and violently abused at home by parents and grownups. Teenagers from abusive, troubled families are far more likely to be depressed and more likely to use social media than non-abused teens.

It is super confusing trying to tease out treatment effects versus selection effects in situations like this. There’s a lot going on. The cyberbullying correlation pretty much has to be causal, because the effect size seems too big to be otherwise.

Bloomberg has an in depth look into the latest scammer tactic: Sextortion.

There is a subreddit with 32k members dedicated to helping victims.

The scam is simple, and is getting optimized as scammers exchange tips.

-

You pretend to be a hot girl, find teenage boy with social media account.

-

You message the teenage boy, express interest, offer to trade nude pics.

-

Teenage boy sends nude pics.

-

Blackmail the boy, threatening to ruin his entire life.

-

If the boy threatens to kill himself, encourage that, for some reason?

Obviously any such story will attempt to be salacious and will select the worst cases.

It still seems highly plausible that this line of work attracts the worst of the worst. That a large portion of them are highly sadistic fs who revel in causing pain and suffering. Who are the types of people who would see suicide threats, actively drive the kid to suicide, and then message his girlfriend and other contacts to blackmail them in turn if they didn’t want the truth about what happened getting out. Yeah.

This is in a very different category than the classic internet scams.

What to do about it, before or after it happens to you?

SwiftOnSecurity: PARENTS: You need to sit your kid down and tell them about sextorsion. They are not going to know randos messaging them for sexting is a trap.

This is a really easy way for criminals onshore and overseas to make money. They convince you to link your real identity. There are suicides after ongoing threats to ruin their life after desperate attempts to pay. And they need to know if they fuck up they need to come to you.

…

Advice thread from a lawyer who deals with sextorsion. DO NOT ENGAGE. Block. Go private. Keep blocking. Show them NO ENGAGEMENT. That spending any time harassing will be worth it. They don’t have a reputation to uphold. Time is money. Apparently they sometimes just give up.

Lane Haygood, Attorney: About once a week I have someone call me in a blind panic about to send hundreds or thousands of dollars to a scammer. My advice to them is always the same: PAY NOTHING. Nothing about paying guarantees the person on the other end will do what they say.

They will continue to extort you as long as you are willing to pay.

The best thing to do is immediately block them. If they message you from new profiles, block, block, block.

The next best thing to do is reach out to an attorney. My brilliant paralegal @KathrynTewson has a great document on cybersecurity we will be happy to provide you with to help ameliorate these things.

All of this strongly matches my intuition. Paying, or engaging at all, raises the expected returns to more blackmail. Nothing they told you or committed to changes that fact, and they are well known liars with no moral compass. No, they are not going to honor their word, in any sense. Meanwhile actually sending the pics gets them nothing. Block, ignore and hope it goes away is the only play on all levels.

He also claims that with the rise of deepfakes you can always run the Shaggy defense if the scammer actually does pull the trigger.

Or you could shrug, if one has perspective. This is not obviously that big a deal, although obviously even if true that is hard for the victim to see.

In particular, one thing that I did not see in the article was talk about admission to college. Colleges will sometimes rescind or deny admission based on a social media post that offends or indicates ordinary kid behavior. Would they do that to a sextortion victim? The chances are not zero, but my guess is it would be rare, given that there is not a known-to-me example of this, and scammers would no doubt lean heavily on this threat if it was a common occurrence.