Do Not Mess With Scarlett Johansson

I repeat. Do not mess with Scarlett Johansson.

You would think her movies, and her suit against Disney, would make this obvious.

Apparently not so.

Andrej Karpathy (co-founder OpenAI, departed earlier), May 14: The killer app of LLMs is Scarlett Johansson. You all thought it was math or something.

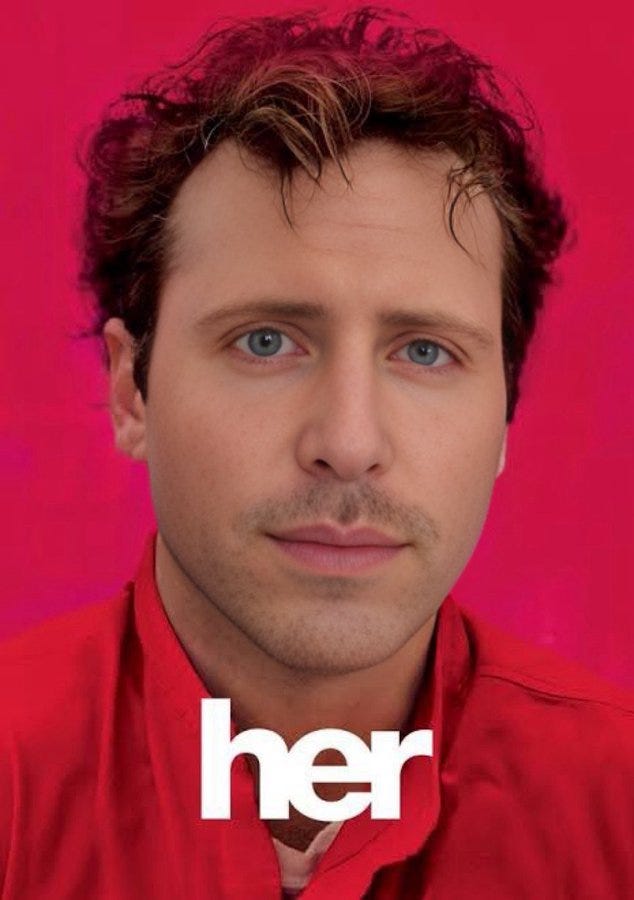

You see, there was this voice they created for GPT-4o, called ‘Sky.’

People noticed it sounded suspiciously like Scarlett Johansson, who voiced the AI in the movie Her, which Sam Altman says is his favorite movie of all time, which he says inspired OpenAI ‘more than a little bit,’ and then he tweeted “Her” on its own right before the GPT-4o presentation, and which was the comparison point for many people reviewing the GPT-4o debut?

I mean, surely that couldn’t have been intentional.

Oh, no.

Kylie Robison: I asked Mira Mutari about Scarlett Johansson-type voice in today’s demo of GPT-4o. She clarified it’s not designed to mimic her, and said someone in the audience asked this exact same question!

Kylie Robison in Verge (May 13): Title: ChatGPT will be able to talk to you like Scarlett Johansson in Her.

OpenAI reports on how it created and selected its five selected GPT-4o voices.

OpenAI: We support the creative community and worked closely with the voice acting industry to ensure we took the right steps to cast ChatGPT’s voices. Each actor receives compensation above top-of-market rates, and this will continue for as long as their voices are used in our products.

We believe that AI voices should not deliberately mimic a celebrity’s distinctive voice—Sky’s voice is not an imitation of Scarlett Johansson but belongs to a different professional actress using her own natural speaking voice. To protect their privacy, we cannot share the names of our voice talents.

…

Looking ahead, you can expect even more options as we plan to introduce additional voices in ChatGPT to better match the diverse interests and preferences of users.

Jessica Taylor: My “Sky’s voice is not an imitation of Scarlett Johansson” T-shirt has people asking a lot of questions already answered by my shirt.

OpenAI: We’ve heard questions about how we chose the voices in ChatGPT, especially Sky. We are working to pause the use of Sky while we address them.

Variety: Altman said in an interview last year that “Her” is his favorite movie.

Variety: OpenAI Suspends ChatGPT Voice That Sounds Like Scarlett Johansson in ‘Her’: AI ‘Should Not Deliberately Mimic a Celebrity’s Distinctive Voice.’

[WSJ had similar duplicative coverage.]

Flowers from the Future: That’s why we can’t have nice things. People bore me.

Again: Do not mess with Scarlett Johansson. She is Black Widow. She sued Disney.

Several hours after compiling the above, I was happy to report that they did indeed mess with Scarlett Johansson.

She is pissed.

Bobby Allen (NPR): Scarlett Johansson says she is ‘shocked, angered’ over new ChatGPT voice.

…

Johansson’s legal team has sent OpenAI two letters asking the company to detail the process by which it developed a voice the tech company dubbed “Sky,” Johansson’s publicist told NPR in a revelation that has not been previously reported.

NPR then published her statement, which follows.

Scarlett Johansson: Last September, I received an offer from Sam Altman, who wanted to hire me to voice the current ChatGPT 4.0 system. He told me that he felt that by my voicing the system, I could bridge the gap between tech companies and creatives and help consumers to feel comfortable with the seismic shift concerning humans and Al. He said he felt that my voice would be comforting to people.

After much consideration and for personal reasons, I declined the offer. Nine months later, my friends, family and the general public all noted how much the newest system named “Sky” sounded like me.

When I heard the released demo, I was shocked, angered and in disbelief that Mr. Altman would pursue a voice that sounded so eerily similar to mine that my closest friends and news outlets could not tell the difference. Mr. Altman even insinuated that the similarity was intentional, tweeting a single word “her” a reference to the film in which I voiced a chat system, Samantha, who forms an intimate relationship with a human.

Two days before the ChatGPT 4.0 demo was released, Mr. Altman contacted my agent, asking me to reconsider. Before we could connect, the system was out there.

As a result of their actions, I was forced to hire legal counsel, who wrote two letters to Mr. Altman and OpenAl, setting out what they had done and asking them to detail the exact process by which they created the “Sky” voice. Consequently, OpenAl reluctantly agreed to take down the “Sky” voice.

In a time when we are all grappling with deepfakes and the protection of our own likeness, our own work, our own identities, I believe these are questions that deserve absolute clarity. I look forward to resolution in the form of transparency and the passage of appropriate legislation to help ensure that individual rights are protected.

This seems like a very clear example of OpenAI, shall we say, lying its ass off?

They say “we believe that AI voices should not deliberately mimic a celebrity’s distinctive voice,” after Sam Altman twice personally asked the most distinctive celebrity possible to be the very public voice of ChatGPT, and she turned them down. They then went with a voice this close to hers while Sam Altman tweeted ‘Her,’ two days after being turned down again. Mira Mutari went on stage and said it was all a coincidence.

Uh huh.

Shakeel: Will people stop suggesting that the attempted-Altman ouster had anything to do with safety concerns now?

It’s increasingly clear that the board fired him for the reasons they gave at the time: he is not honest or trustworthy, and that’s not an acceptable trait for a CEO!

for clarification: perhaps the board was particularly worried about his untrustworthiness *becauseof how that might affect safety. But the reported behaviour from Altman ought to have been enough to get him fired at any company!

There are lots of ethical issues with the Scarlett Johansson situation, including consent.

But one of the clearest cut issues is dishonesty. Earlier today, OpenAI implied it’s a coincidence that Sky sounded like Johansson. Johansson’s statement suggests that is not at all true.

This should be a big red flag to journalists, too — it suggests that you cannot trust what OpenAI’s comms team tells you.

Case in point: Mira Murati appears to have misled Verge reporter Kylie Robison.

And it seems they’re doubling down on this, with carefully worded statements that don’t really get to the heart of the matter:

-

Did they cast Sky because she sounded like Johansson?

-

Did Sky’s actress aim to mimic the voice of Scarlett Johansson?

-

Did OpenAI adjust Sky’s voice to sound more like Scarlett Johansson?

-

Did OpenAI outright train on Scarlett Johansson’s voice?

I assume not that fourth one. Heaven help OpenAI if they did that.

Here is one comparison of Scarlett talking normally, Scarlett’s voice in Her and the Sky voice. The Sky voice sample there was plausibly chosen to be dissimilar, so here is another longer sample in-context, from this OpenAI demo, that is a lot closer to my eears. I do think you can still tell the difference between Scarlett Johansson and Sky, but it is then not so easy. Opinions differ on exactly how close the voices were. To my ears, the sample in the first clip sounds more robotic, but in the second clip it is remarkably close.

No one is buying that this is a coincidence.

Another OpenAI exec seems to have misled Nitasha Tiku.

Nitasha Tiku: the ScarJo episode gives me an excuse to revisit one of the most memorable OpenAI demos I’ve had the pleasure of attending. back in Septemberwhen the company first played the “Sky” voice, I told the exec in charge it sounded like ScarJo and asked him if it was intentional.

He said no, there are 5 voices, it’s just personal pref. Then he said he uses ChatGPT to tell bedtime stories and his son prefers certain voices. Pinnacle of Tech Dad Demo, unlocked.

Even if we take OpenAI’s word for absolutely everything, the following facts do not appear to be in dispute:

-

Sam Altman asked Scarlett Johansson to be the voice of their AI, because of Her.

-

She said no.

-

OpenAI created an AI voice most people think sounded like Scarlett Johansson.

-

OpenAI claimed repeatedly that Sky’s resemblance to Johansson is a coincidence.

-

OpenAI had a position that voices should be checked for similarity to celebrities.

-

Sam Altman Tweeted ‘Her.’

-

They asked her permission again.

-

They decided This Is Fine and did not inform Scarlett Johansson of Sky.

-

Two days after asking her permission again they launched the voice of Sky.

-

They did so in a presentation everyone paralleled to Scarlett Johansson.

So, yeah.

On March 29, 2024, OpenAI put out a post entitled Navigating the Challenges and Opportunities of Synthetic Voices (Hat tip).

They said this, under ‘Building Voice Engine safely.’ Bold mine:

OpenAI: Finally, we have implemented a set of safety measures, including watermarking to trace the origin of any audio generated by Voice Engine, as well as proactive monitoring of how it’s being used.

We believe that any broad deployment of synthetic voice technology should be accompanied by voice authentication experiences that verify that the original speaker is knowingly adding their voice to the service and a no-go voice list that detects and prevents the creation of voices that are too similar to prominent figures.

If I was compiling a list of voices to check in this context that were not political figures, Scarlett Johansson would not only have been on that list.

She would have been the literal first name on that list.

For exactly the same reason we are having this conversation.

GPT-4o did not factor in Her, so it put her in the top 100 but not top 50, and even with additional context would only have put her in the 10-20 range with the Pope, the late Queen and Taylor Swift (who at #15 was the highest non-CEO non-politician.)

Remember that in September 2023, a journalist asked an OpenAI executive about Sky and why it sounded so much like Scarlett Johansson.

Even if this somehow was all an absurd coincidence, there is no excuse.

Ultimately, I think that the voices absolutely should, when desired by the user, mimic specific real people’s voices, with of course that person’s informed consent, participation and financial compensation.

I should be able to buy or rent the Scarlett Johansson voice package if I want that and she decides to offer one. She ideally gets most or all of that money. Everybody wins.

If she doesn’t want that, or I don’t, I can go with someone else. You could buy any number of them and swap between them, have them in dialogue, whatever you want.

You can include a watermark in the audio for deepfake detection. Even without that, it is not as if this makes deepfaking substantially harder. If you want to deepfake Scarlett Johansson’s voice without her permission there are publically available tools you can already use to do that.

Once could even say the facts went almost maximally badly, short of an outright deepfake.

Bret Devereaux: Really feels like some of these AI fellows needs to suffer some more meaningful legal repercussions for stealing peoples art, writing, likeness and freakin’ voices so they adopt more of an ‘ask permission’ rather than an ‘ask forgiveness’ ethos.

Trevor Griffey:Did he ask for forgiveness?

Linch: He asked for permission but not forgiveness lmao.

Bret Devereaux: To be more correct, he asked permission, was told no, asked permission again, then went and did it anyway before he got permission, and then hoped no one would notice, while he tweeted to imply that he had permission, when he didn’t.

Which seems worse, to be frank?

Mario Cannistra (other thread): Sam obviously lives by “better ask for forgiveness than permission”, as he’s doing the same thing with AGI. He’ll say all the nice words, and then he’ll do it anyway, and if it doesn’t go as planned, he’ll deal with it later (when we’re all dead).

Zvi: In this case, he made one crucial mistake: The first rule of asking forgiveness rather than permission is not to ask for permission.

The second rule is to ask for permission.

Whoops, on both counts.

Also it seems they lied repeatedly about the whole thing.

That’s the relatively good scenario, where there was no outright deepfake, and her voice was not directly used in training.

I am not a lawyer, but my read is: Oh yes. She has a case.

A jury would presumably conclude this was intentional, even if no further smoking guns are found in discovery. They asked Scarlett Johansson twice to participate. There were the references to ‘Her.’

There is no fully objective way to present the facts to an LLM, your results may vary, but when I gave GPT-4o a subset of the evidence that would be presented by Scarlett’s lawyers, plus OpenAI’s claims it was a coincidence, GPT-4o put the probability of a coincidence at under 10%.

It all seems like far more than enough for a civil case, especially given related public attitudes. This is not going to be a friendly jury for OpenAI.

If the voice actress was using her natural voice (or the ‘natural robotization’ thereof) without any instructions or adjustments that increased the level of resemblance, and everyone was careful not to ever say anything beyond what we already know, and the jury is in a doubting mood? Even then I have a hard time seeing it.

If you intentionally imitate someone’s distinctive voice and style? That’s a paddlin.

Paul Feldman (LA Times, May 9, 1990): In a novel case of voice theft, a Los Angeles federal court jury Tuesday awarded gravel-throated recording artist Tom Waits $2.475 million in damages from Frito-Lay Inc. and its advertising agency.

The U.S. District Court jury found that the corn chip giant unlawfully appropriated Waits’ distinctive voice, tarring his reputation by employing an impersonator to record a radio ad for a new brand of spicy Doritos corn chips.

…

While preparing the 1988 ad, a Tracy-Locke copywriter listened repeatedly to Waits’ tune, “Step Right Up,” and played the recording for Frito-Lay executives at a meeting where his script was approved. And when singer Steve Carter, who imitates Waits in his stage act, performed the jingle, Tracy-Locke supervisors were concerned enough about Carter’s voice that they consulted a lawyer, who counseled caution.

Then there’s the classic case Midler v. Ford Motor Company. It sure sounds like a direct parallel to me, down to asking for permission, getting refused, doing it anyway.

Jack Despain Zhou: Fascinating. This is like a beat-for-beat rehash of Midler v. Ford Motor Co.

Companies have tried to impersonate famous voices before when they can’t get those voices. Generally doesn’t go well for the company.

Wikipedia: Ford Motor created an ad campaign for the Mercury Sable that specifically was meant to inspire nostalgic sentiments through the use of famous songs from the 1970s sung by their original artists. When the original artists refused to accept, impersonators were used to sing the original songs for the commercials.

Midler was asked to sing a famous song of hers for the commercial and refused.

Subsequently, the company hired a voice-impersonator of Midler and carried on with using the song for the commercial, since it had been approved by the copyright-holder. Midler’s image and likeness were not used in the commercial but many claimed the voice used sounded impeccably like Midler’s.

Midler brought the case to a district court where she claimed that her voice was protected from appropriation and thus sought compensation. The district court claimed there was no legal principle preventing the use of her voice and granted summary judgment to Ford Motor. Midler appealed to the Appellate court, 9th Circuit.

…

The appellate court ruled that the voice of someone famous as a singer is distinctive to their person and image and therefore, as a part of their identity, it is unlawful to imitate their voice without express consent and approval. The appellate court reversed the district court’s decision and ruled in favor of Midler, indicating her voice was protected against unauthorized use.

If it has come to this, so be it.

Ross Douthat: Writing a comic novel about a small cell of people trying to stop the rise of a demonic super-intelligence whose efforts are totally ineffectual but then in the last chapter Scarlett Johansson just sues the demon into oblivion.

Fredosphere: Final lines:

AI: “But what will become of me?”

Scarlett: “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

Genius. Also, I’d take it. A win is a win.

There are some people asking what the big deal is, ethically, practically or legally.

In legal terms, my most central observation is that those who don’t see the legal issue mostly are unaware of the relevant prior case law listed above due to being unwilling to Google for it or ask an LLM.

I presume everyone agrees that an actual direct deepfake, trained on the voice of Scarlett Johansson without consent, would be completely unacceptable.

The question some ask is, if it is only a human that was ‘training on the voice of Scarlett Johansson,’ similar to the imitators in the prior cases, why should we care? Or, alternatively, if OpenAI searched for the closest possible match, how is that different from when Padme is not available for a task so you send out a body double?

The response ‘I never explicitly told people this was you, fine this is not all a coincidence, but I have a type I wanted and I found an uncanny resemblance and then heavily dropped references and implications’ does not seem like it should work here? At least, not past some point?

Obviously, you are allowed to (even if it is kind of creepy) date someone who looks and sounds suspiciously like your ex, or (also creepy) like someone who famously turned you down, or to recast a voice actor while prioritizing continuity or with an idea of what type of voice you are looking for.

It comes down to whether you are appropriating someone’s unique identity, and especially whether you are trying to fool other observers.

The law must also adjust to the new practicalities of the situation, in the name of the ethical and practical goals that most of us agree on here. As technology and affordances change, so must the rules adjust.

In ethical and practical terms, what happens if OpenAI is allowed to do this while its motivations and source are plain as day, so long as the model did not directly train on Scarlett Johansson’s voice?

You do not need to train an AI directly on Scarlett’s voice to get arbitrarily close to Scarlett’s voice. You can get reasonably close even if all you have is selection among unaltered and uncustomized voices, if you have enough of a sample to choose from.

If you auditioned women of similar age and regional accent, your chances of finding a close soundalike are remarkably good. Even if that is all OpenAI did to filter initial applications, and then they selected the voice of Sky to be the best fit among them, auditioning 400 voices for 5 slots is more than enough.

I asked GPT-4o what would happen if you also assume professional voice actresses were auditioning for this role, and they understood who the target was. How many would you have to test before you were a favorite to find a fit that was all but indistinguishable?

One. It said 50%-80% chance. If you audition five, you’re golden.

Then the AI allows this voice to have zero marginal cost to reproduce, and you can have it saying absolutely anything, anywhere. That, alone, obviously cannot be allowed.

Remember, that is before you do any AI fine-tuning or digital adjustments to improve the match. And that means, in turn, if you did use an outright deepfake or you did fine-tuning on the closeness of match or used it to alter parameters in post, unless they can retrace your steps who is to say you did any of that.

If Scarlett Johansson does not have a case here, where OpenAI did everything in their power to make it obvious and she has what it takes to call them on it, then there effectively are very close to no rules and no protections, for creatives or otherwise, except for laws against outright explicitly claimed impersonations, scams and frauds.

As I have said before:

Many of our laws and norms will need to adjust to the AI era, even if the world mostly ‘looks normal’ and AIs do not pose or enable direct existential or catastrophic risks.

Our existing laws rely on friction, and on human dynamics of norm enforcement. They and their consequences are designed with the expectation of uneven enforcement, often with rare enforcement. Actions have practical costs and risks, most of them very different from zero, and people only have so much attention and knowledge and ability to execute and we don’t want to stress out about all this stuff. People and corporations have reputations to uphold and they have to worry about unknown unknowns where there could be (metaphorical) dragons. One mistake can land us or a company in big trouble. Those who try to break norms and laws accumulate evidence, get a bad rep and eventually get increasingly likely to be caught.

In many places, fully enforcing the existing laws via AI and AI-enabled evidence would grind everything to a halt or land everyone involved in prison. In most cases that is a bad result. Fully enforcing the strict versions of verbally endorsed norms would often have a similar effect. In those places, we are going to have to adjust.

Often we are counting on human discretion to know when to enforce the rules, including to know when a violation indicates someone who has broken similar rules quite a lot in damaging ways versus someone who did it this once because of pro-social reasons or who can learn from their mistake.

If we do adjust our rules and our punishments accordingly, we can get to a much better world. If we don’t adjust, oh no.

Then there are places (often overlapping) where the current rules let people get away with quite a lot, often involving getting free stuff, often in a socially damaging way. We use a combination of ethics and shame and fear and reputation and uncertainty and initial knowledge and skill costs and opportunity costs and various frictions to keep this at an acceptable level, and restricted largely to when it makes sense.

Breaking that equilibrium is known as Ruining It For Everyone.

A good example would be credit card rewards. If you want to, you can exploit various offers to make remarkably solid money opening and abusing various cards in various ways, and keep that going for quite a while. There are groups for this. Same goes for sportsbook deposit bonuses, or the return policies at many stores, and so on.

The main reason that often This Is Fine is that if you are sufficiently competent to learn and execute on such plans, you mostly have better things to do, and the scope on any individual’s actions are usually self-limiting (when they aren’t you get rules changes and hilarious news stories.) And what is lost to such tricks is made up for elsewhere. But if you could automate these processes, then the scope goes to infinity, and you get rules changes and ideally hilarious (but often instead sad) news articles. You also get mode collapses when the exploits become common knowledge or too easy to do, and norms against using them go away.

Another advantage is this is often good price discrimination gated by effort and attention, and an effective subsidy for the poor. You can ‘work the job’ of optimizing such systems, which is a fallback if you don’t have better opportunities, and you are short on money but long on time or want to train optimization or pull one over.

AI will often remove such frictions, and the barriers preventing rather large scaling.

AI voice imitation is one of those cases. Feature upgrades, automation, industrialization and mass production change the nature of the beast. This particular case was one that was already illegal without AI because it is so brazen and clear cut, but we are going to have to adjust our rules to the general case.

The good news is this is a case where the damage is limited, so ‘watch for where things go wrong and adjust’ should work fine. This is the system working.

The bad news is that this adjustment cannot involve ‘stop the proliferation of technology that allows voice cloning from remarkably small samples.’ That technology is essentially mature already, and open solutions available. We cannot unring the bell.

In other places, where the social harms can scale to a very high level, and the technological bell once rung cannot be easily unrung, we have a much harder problem. That is a discussion for another post.

As noted above, there was a faction that said this was no big deal, or even totally fine.

Most people did not see it that way. The internet is rarely as united as this.

Nate Silver: Very understandably negative reaction to OpenAI on this. It is really uniting people in different political tribes, which is not easy to do on Twitter.

One of the arguments I make in my book—and one of the reasons my p(doom) is lower than it might be—is that AI folks underestimate the potential for a widespread political backlash against their products.

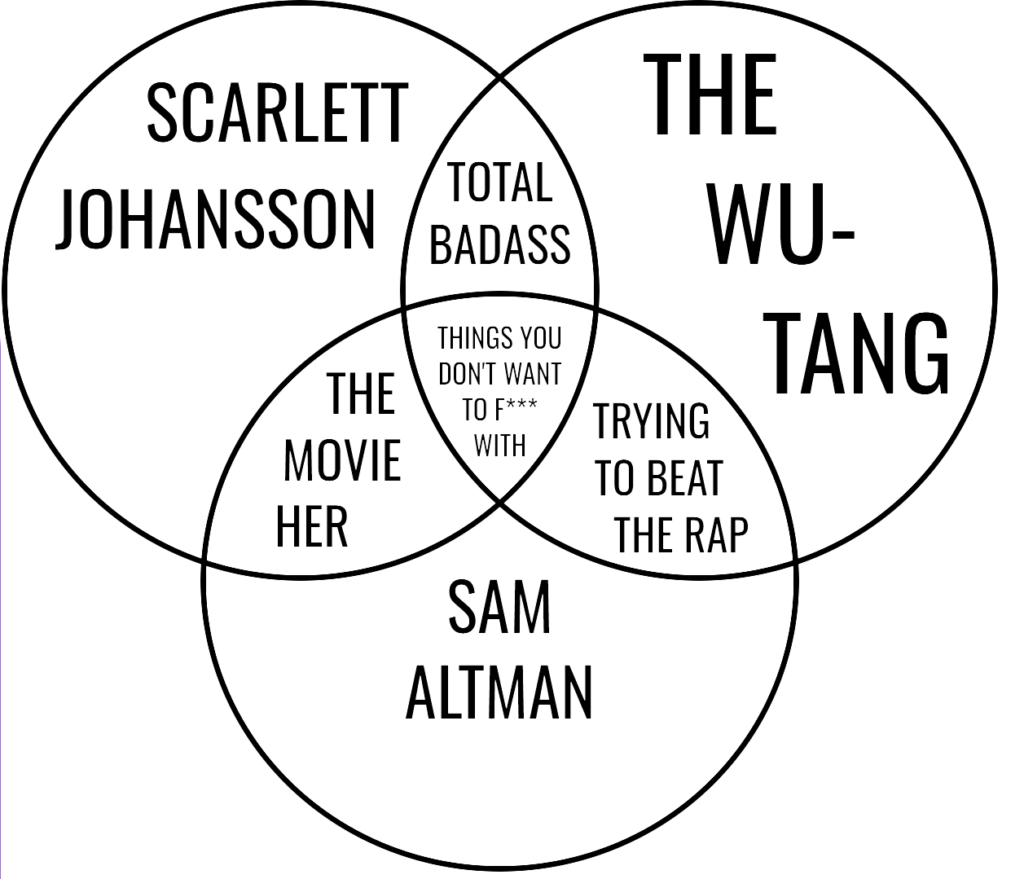

Do not underestimate the power of a beloved celebrity that is on every level a total badass, horrible publicity and a united internet.

Conor Sen: Weird stuff on Sam’s part in addition to any other issues it raises.

Now whenever a reporter or politician is trying to point out the IP issues of AI they can say “Sam stole ScarJo’s voice even after she denied consent.” It’s a much easier story to sell to the general public and members of Congress.

Noah Giansiracusa: This is absolutely appalling. Between this and the recent NDA scandal, I think there’s enough cause for Altman to step down from his leadership role at OpenAI. The world needs a stronger moral compass at the helm of such an influential AI organization.

There’s even some ethics people out there to explain other reasons this is problematic.

Kate Crawford: Why did OpenAI use Scarlett Johansson’s voice? As Jessa Lingel & I discuss in our journal article on AI agents, there’s a long history of using white women’s voices to “personalize” a technology to make it feel safe and non-threatening while it is capturing maximum data.

Sam Altman has said as much. NYT: he told ScarJo her voice would help “consumers to feel comfortable with the seismic shift concerning humans and AI” as her voice “would be comforting to people.”

AI assistants invoke gendered traditions of the secretary, a figure of administrative and emotional support, often sexualized. Underpaid and undervalued, secretaries still had a lot of insight into private and commercially sensitive dealings. They had power through information.

But just as secretaries were taught to hide their knowledge, AI agents are designed to make us to forget their power as they are made to fit within non-threatening, retrograde feminine tropes. These are powerful data extraction engines, sold as frictionless convenience.

Finally, for your moment of zen: The Daily Show has thoughts on GPT-4o’s voice.

Do Not Mess With Scarlett Johansson Read More »