Nvidia announces “moonshot” to create embodied human-level AI in robot form

Here come the robots —

As companies race to pair AI with general-purpose humanoid robots, Nvidia’s GR00T emerges.

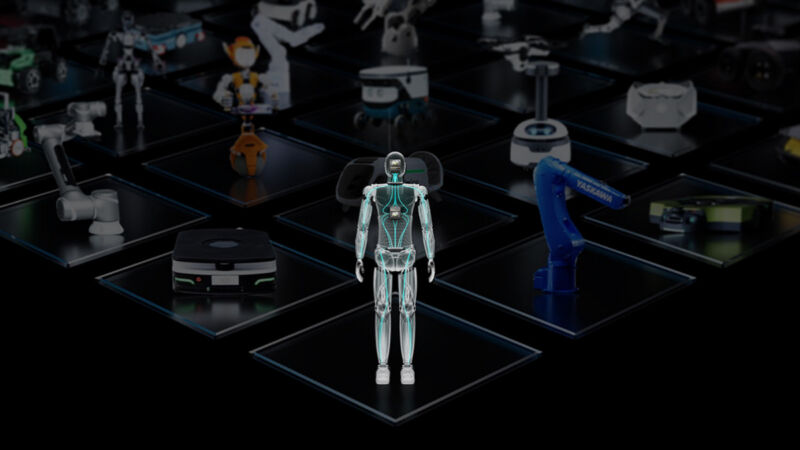

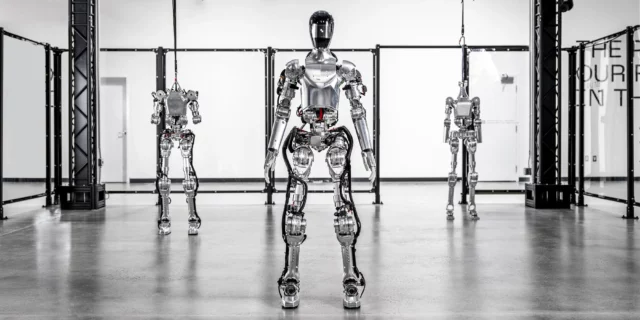

Enlarge / An illustration of a humanoid robot created by Nvidia.

Nvidia

In sci-fi films, the rise of humanlike artificial intelligence often comes hand in hand with a physical platform, such as an android or robot. While the most advanced AI language models so far seem mostly like disembodied voices echoing from an anonymous data center, they might not remain that way for long. Some companies like Google, Figure, Microsoft, Tesla, Boston Dynamics, and others are working toward giving AI models a body. This is called “embodiment,” and AI chipmaker Nvidia wants to accelerate the process.

“Building foundation models for general humanoid robots is one of the most exciting problems to solve in AI today,” said Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang in a statement. Huang spent a portion of Nvidia’s annual GTC conference keynote on Monday going over Nvidia’s robotics efforts. “The next generation of robotics will likely be humanoid robotics,” Huang said. “We now have the necessary technology to imagine generalized human robotics.”

To that end, Nvidia announced Project GR00T, a general-purpose foundation model for humanoid robots. As a type of AI model itself, Nvidia hopes GR00T (which stands for “Generalist Robot 00 Technology” but sounds a lot like a famous Marvel character) will serve as an AI mind for robots, enabling them to learn skills and solve various tasks on the fly. In a tweet, Nvidia researcher Linxi “Jim” Fan called the project “our moonshot to solve embodied AGI in the physical world.”

AGI, or artificial general intelligence, is a poorly defined term that usually refers to hypothetical human-level AI (or beyond) that can learn any task a human could without specialized training. Given a capable enough humanoid body driven by AGI, one could imagine fully autonomous robotic assistants or workers. Of course, some experts think that true AGI is long way off, so it’s possible that Nvidia’s goal is more aspirational than realistic. But that’s also what makes Nvidia’s plan a moonshot.

NVIDIA Robotics: A Journey From AVs to Humanoids.

“The GR00T model will enable a robot to understand multimodal instructions, such as language, video, and demonstration, and perform a variety of useful tasks,” wrote Fan on X. “We are collaborating with many leading humanoid companies around the world, so that GR00T may transfer across embodiments and help the ecosystem thrive.” We reached out to Nvidia researchers, including Fan, for comment but did not hear back by press time.

Nvidia is designing GR00T to understand natural language and emulate human movements, potentially allowing robots to learn coordination, dexterity, and other skills necessary for navigating and interacting with the real world like a person. And as it turns out, Nvidia says that making robots shaped like humans might be the key to creating functional robot assistants.

The humanoid key

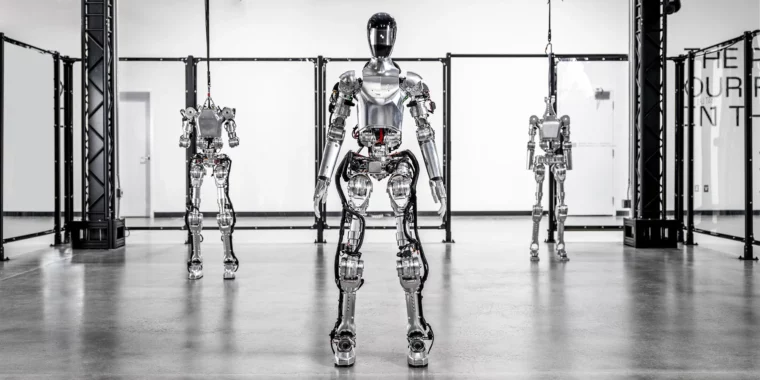

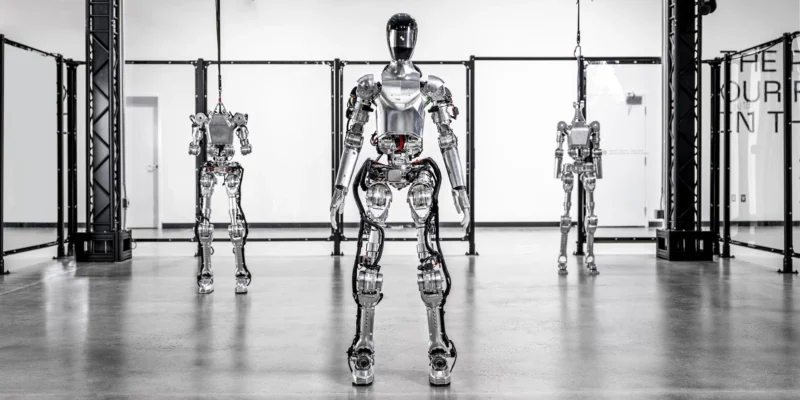

Enlarge / Robotics startup figure, an Nvidia partner, recently showed off its humanoid “Figure 01” robot.

Figure

So far, we’ve seen plenty of robotics platforms that aren’t human-shaped, including robot vacuum cleaners, autonomous weed pullers, industrial units used in automobile manufacturing, and even research arms that can fold laundry. So why focus on imitating the human form? “In a way, human robotics is likely easier,” said Huang in his GTC keynote. “And the reason for that is because we have a lot more imitation training data that we can provide robots, because we are constructed in a very similar way.”

That means that researchers can feed samples of training data captured from human movement into AI models that control robot movement, teaching them how to better move and balance themselves. Also, humanoid robots are particularly convenient because they can fit anywhere a person can, and we’ve designed a world of physical objects and interfaces (such as tools, furniture, stairs, and appliances) to be used or manipulated by the human form.

Along with GR00T, Nvidia also debuted a new computer platform called Jetson Thor, based on NVIDIA’s Thor system-on-a-chip (SoC), as part of the new Blackwell GPU architecture, which it hopes will power this new generation of humanoid robots. The SoC reportedly includes a transformer engine capable of 800 teraflops of 8-bit floating point AI computation for running models like GR00T.

Nvidia announces “moonshot” to create embodied human-level AI in robot form Read More »