Reading Lord of the Rings aloud: Yes, I sang all the songs

It’s not easy, but you really can sing in Elvish if you try!

Yes, it will take a while to read.

Like Frodo himself, I wasn’t sure we were going to make it all the way to the end of our quest. But this week, my family crossed an important life threshold: every member has now heard J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (LotR) read aloud—and sung aloud—in its entirety.

Five years ago, I read the series to my eldest daughter; this time, I read it for my wife and two younger children. It took a full year each time, reading 20–45 minutes before bed whenever we could manage it, to go “there and back again” with our heroes. The first half of The Two Towers, with its slow-talking Ents and a scattered Fellowship, nearly derailed us on both reads, but we rallied, pressing ahead even when iPad games and TV shows appeared more enticing. Reader, it was worth the push.

Gollum’s ultimate actions on the edge of the Crack of Doom, the final moments of Sauron and Saruman as impotent mists blown off into the east, Frodo’s woundedness and final ride to the Grey Havens—all of it remains powerful and left a suitable impression upon the new listeners.

Reading privately is terrific, of course, and faster—but performing a story aloud, at a set time and place, creates a ritual that binds the listeners together. It forces people to experience the story at the breath’s pace, not the eye’s. Besides, we take in information differently when listening.

An audiobook could provide this experience and might be suitable for private listening or for groups in which no one has a good reading voice, but reading performance is a skill that can generally be honed. I would encourage most people to try it. You will learn, if you pay close attention as you read, how to emphasize and inflect meaning through sound and cadence; you will learn how to adopt speech patterns and “do the voices” of the various characters; you will internalize the rhythms of good English sentences.

Even if you don’t measure up to the dulcet tones of your favorite audiobook narrator, you will improve measurably over a year, and (more importantly) you will create a unique experience for your group of listeners. Improving one’s reading voice pays dividends everywhere from the boardroom to the classroom to the pulpit. Perhaps it will even make your bar anecdotes more interesting.

Humans are fundamentally both storytellers and story listeners, and the simple ritual of gathering to tell and listen to stories is probably the oldest and most human activity that we participate in. Greg Benford referred to humanity as “dreaming vertebrates,” a description that elevates the creation of stories into an actual taxonomic descriptor. You don’t have to explain to a child how to listen to a story—if it’s good enough, the kid will sit staring at you with their mouth wide open as you tell it. Being enthralled by a story is as automatic as breathing because storytelling is as basic to humanity as breathing.

Yes, LotR is a fantasy with few female voices and too many beards, but its understanding of hope, despair, history, myth, geography, providence, community, and evil—much more subtle than Tolkien is sometimes given credit for—remains keen. And it’s an enthralling story. Even after reading it five times, twice aloud, I was struck again on this read-through by its power, which even its flaws cannot dim.

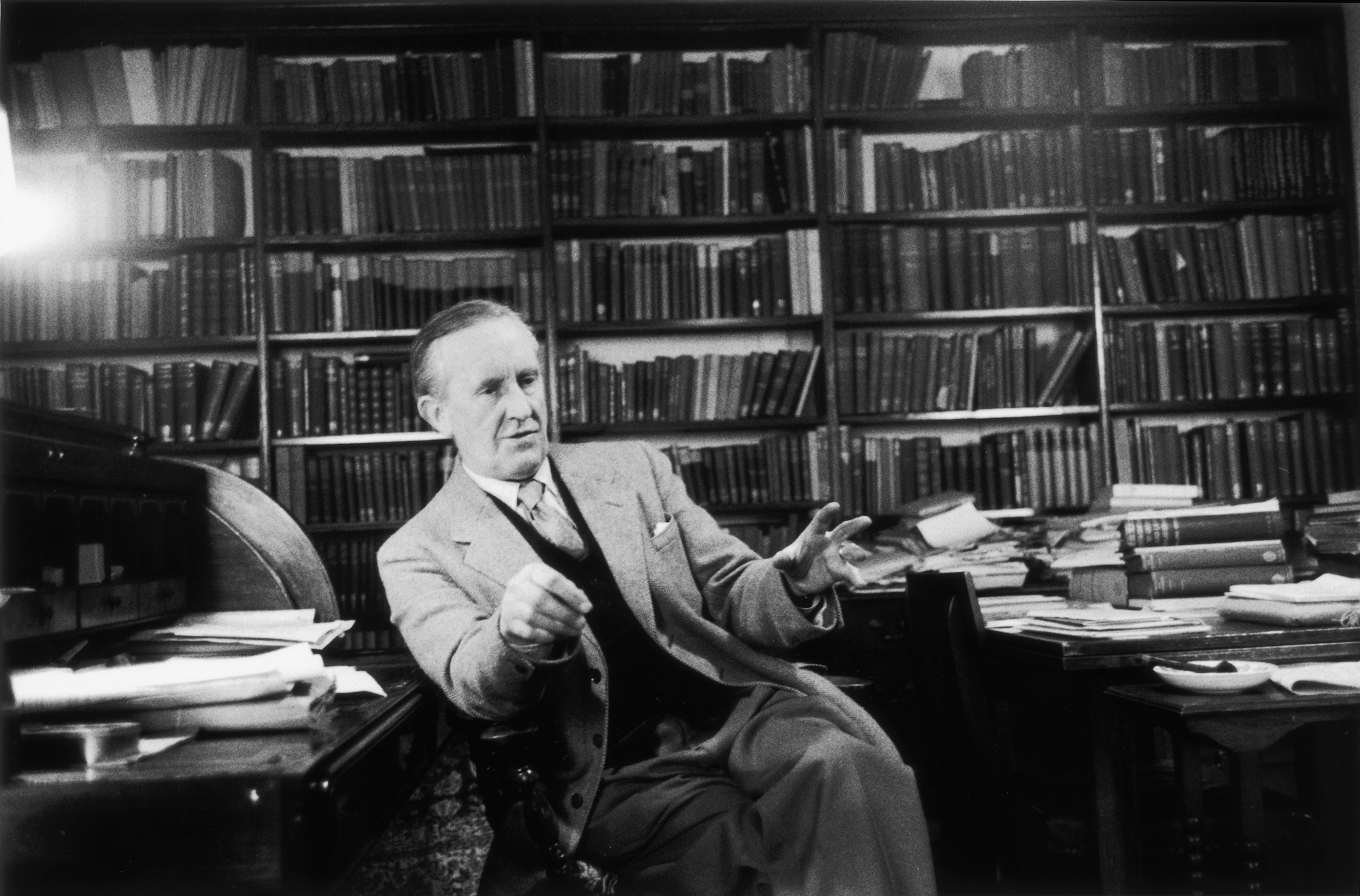

I spent years in English departments at the undergraduate and graduate levels, and the fact that I could take twentieth-century British lit classes without hearing the name “Tolkien” increasingly strikes me as a short-sighted and somewhat snobbish approach to an author who could be consciously old-fashioned but whose work remains vibrant and alive, not dead and dusty. Tolkien was a “strong” storyteller who bent tradition to his will and, in doing so, remade it, laying out new roads for the imagination to follow.

Given the amount of time that a full read-aloud takes, it’s possible this most recent effort may be my last with LotR. (Unless, perhaps, with grandchildren?) With that in mind, I wanted to jot down a few reflections on what I learned from doing it twice. First up is the key question: What are we supposed to do with all that poetry?

Songs and silences

Given the number of times characters in the story break into song, we might be justified in calling the saga Lord of the Rings: The Musical. From high to low, just about everyone but Sauron bursts into music. (And even Sauron is poet enough to inscribe some verses on the One Ring.)

Hobbits sing, of course, usually about homely things. Bilbo wrote the delightful road song that begins, “The road goes ever on and on,” which Frodo sings it when he leaves Bag End; Bilbo also wrote a “bed song” that the hobbits sing on a Shire road at twilight before a Black Rider comes upon them. In Bree, Frodo jumps upon a table and performs a “ridiculous song” that includes the lines, “The ostler has a tipsy cat / that plays a five-stringed fiddle.”

Hobbits sing also in moments of danger or distress. Sam, for instance, sitting alone in the orc stronghold of Cirith Ungol while looking for the probably dead Frodo, rather improbably bursts into a song about flowers and “merry finches.”

Dwarves sing. Gimli—not usually one for singing—provides the history of his ancestor Durin in a chant delivered within the crushing darkness of Moria.

No harp is wrung, no hammer falls:

The darkness dwells in Durin’s halls;

The shadow lies upon his tomb

In Moria, in Khazad-dûm.

After this, “having sung his song he would say no more.”

Elves sing, of course—it’s one of their defining traits. And so Legolas offers the company a song—in this case, about an Elvish beauty named Nimrodel and a king named Amroth—but after a time, he “faltered, and the song ceased.” Even songs that appear to be mere historical ballads are surprisingly emotional; they touch on deep feelings of place or tribe or loss, things difficult to put directly into prose.

“The great” also take diva turns in the spotlight, including Galadriel, who sings in untranslated Elvish when the Fellowship leaves her land. As a faithful reader, you will have to power through 17 lines as your children look on with astonishment while you try to pronounce:

Ai! laurië lantar lassi súrinen

yéni únótimë ve rámar aldaron!

Yéni ve lintë yuldar avánier

mi oromardi lisse-miruvóreva…

You might expect that Gandalf, of all characters, would be most likely to cock an eyebrow, blow a smoke ring, and staunchly refuse to perform “a little number” in public. And you’d be right… until the moment when even he bursts out into a song about Galadriel while in the court of Théoden. Wizards are not perhaps great poets, but there’s really no excuse for lines like “Galadriel! Galadriel! Clear is the water of your well.” We can’t be too hard on Gandalf, of course; coming back from the dead is a tough trip, and no one’s going to be at their best for quite a while.

Even the mysterious and nearly ageless entities of Middle Earth, such as Tom Bombadil and Treebeard the Ent, sing as much as they can. Treebeard likes to chant about “the willow-meads of Tasarinan” and the “elm-woods of Ossiriand.” If you let him, he’ll warble on about his walks in “Ambaróna, in Tauremorna, in Aldalómë” and the time he hung out in “Taur-na-neldor” and that one special winter in “Orod-na-Thôn.” Tough stuff for the reader to pronounce or understand!

In an easier (but somewhat daffier) vein, the spritely Tom Bombadil communicates largely in song. He regularly bursts out with lines like “Hey! Come derry dol! Hop along, my hearties! / Hobbits! Ponies all! We are fond of parties” and “Ho! Tom Bombadil, Tom Bombadillo!”

When people in LotR aren’t occupying their mouths with song, poetry is the order of the day.

You might get a three-page epic about Eärendil the mariner that is likely to try the patience of even the hardiest reader, especially with lines like “of silver was his habergeon / his scabbard of chalcedony.” After powering through all this material, you get as your reward—the big finish!—a thudding conclusion: “the Flammifer of Westernesse.” There is no way, reading this aloud, not to sound faintly ridiculous.

In recompense, though, you also get earthy verse that can be truly delightful, such as Sam’s lines about the oliphaunt: “Grey as a mouse / Big as a house, / Nose like a snake / I make the earth shake…” If I still had small children, I would absolutely buy the picture book version of this poem.

Reading LotR aloud forces one to reckon with all of this poetry; you can’t simply let your eye race across it or your attention wander. I was struck anew in this read-through by just how much verse is a part of this world. It belongs to almost every race (excepting perhaps the orcs?) and class, and it shows up in most chapters of the story. Simply flipping through the book and looking for the italicized verses is itself instructive. This material matters.

Tolkien loved writing verse, and a three-volume hardback set of his “collected poems” just appeared in September. But the sheer volume of all the poetic material in LotR poses a real challenge for anyone reading aloud. Does one simply read it all? Truncate parts? Skip some bits altogether? And when it comes to the songs, there’s the all-important question: Will you actually sing them?

“You’re not going to sing my many songs? What are you, a filthy orc?”

Perform the poetry, sing the songs

As the examples above indicate, the book’s many poetic sections are, to put it mildly, of varying quality. (In December 1937, a publisher’s reader called one of Tolkien’s long poems “very thin, if not downright bad.”) Still, I made the choice to read every word of every poem and to sing every word of every song, making up melodies on the fly.

This was not always “successful,” but it did mean that my children perked up with great glee whenever they sensed a song in the distance. There’s nothing quite like watching a parent struggle to perform lines in elvish to keep kids engaged in what might otherwise be off-putting, especially to those not deeply into the “lore” aspects of Middle-Earth. And coming up with melodies forced me as the reader to be especially creative—a good discipline of its own!

I thought it important to preserve the feel of all this poetic material, even when that feeling was confusion or boredom, to give my kids the true epic sense of the novel. Yes, my listeners continually forgot who Eärendil was or why Westernesse was so important, but even without full understanding, these elements hint at the deep background of this world. They are a significant part of its “feel” and lore.

The poetic material is also an important part of Tolkien’s vision of the good life. Some of it can feel contrived or self-consciously “epic,” but even these poems and songs create a world in which poetry, music, and song are not restricted to professionals; they have historically been part of the fabric of normal life, part of a lost world of fireplaces, courtly halls, churches, and taverns where amateur, public song and poetry used to flourish. In a world where poetry has retreated into the academy and where most song is recorded, Tolkien offers a different vision for how to use verse. (Songs build community, for instance, and are rarely sung in isolation but are offered to others in company.)

The poetic material can also be used as a teaching aid. It shows various older formal possibilities, and not all of these are simple rhymes. Tolkien was no modernist, of course, and there’s no vers libre on display here, but Tolkien loved (and translated) Anglo-Saxon poetry, which is based not on rhyme or even syllabic rhythm but on alliteration. Any particular line of poetry in this fashion will feature two to four alliterative positions that rely for their effect on the repetitive thump of the same sound.

If this is new to you, take a moment and actually read the following example aloud, giving subtle emphasis to the three “r” sounds in the first line, the three initial “d” sounds in the second, and the two “h” sounds in the third:

Arise now, arise, Riders of Théoden!

Dire deeds away, dark is it eastward.

Let horse be bridled, horn be sounded!

This kind of verse is used widely in Rohan. It can be quite thrilling to recite aloud, and it provides a great way to introduce young listeners to a different (and still powerful) poetic form. It also provides a nice segue, once LotR is over, to suggest a bit more Tolkien Anglo-Saxonism by reading his translations of Beowulf or Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

The road ahead

If there’s interest in this sort of thing, in future installments, I’d like to cover:

- The importance of using maps when reading aloud

- How to keep the many, many names (and their many, many variants!) clear in readers’ minds

- Doing (but not overdoing) character voices

- How much backstory to fill in for new readers (Westernesse? The Valar? Morgoth?)

- Making mementos to remind people of your long reading journey together

But for now, I’d love to hear your thoughts on reading aloud, handling long books like LotR (finding time and space, pacing oneself, etc), and vocal performance. Most importantly: Do you actually sing all the songs?

Reading Lord of the Rings aloud: Yes, I sang all the songs Read More »