Natural disasters are a rising burden for the National Guard

New Pentagon data show climate impacts shaping reservists’ mission.

National Guard soldiers search for people stranded by flooding in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene on September 27, 2024, in Steinhatchee, Florida. Credit: Sean Rayford/Getty Images

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy, and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

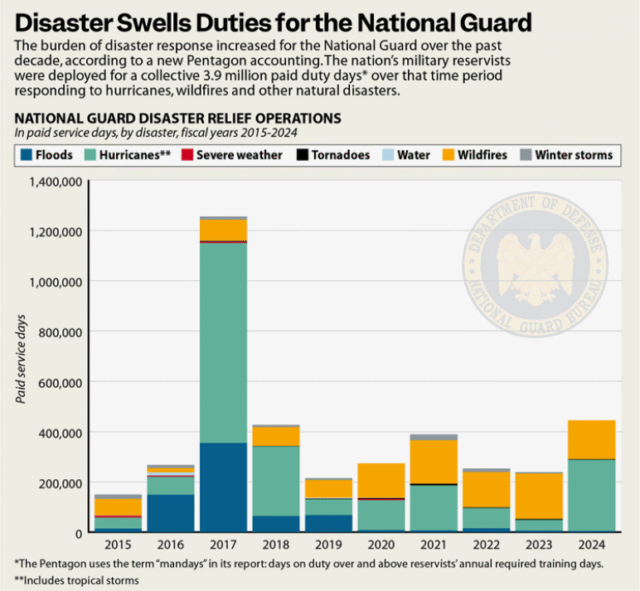

The National Guard logged more than 400,000 member service days per year over the past decade responding to hurricanes, wildfires, and other natural disasters, the Pentagon has revealed in a report to Congress.

The numbers mean that on any given day, 1,100 National Guard troops on average have been deployed on disaster response in the United States.

Congressional investigators believe this is the first public accounting by the Pentagon of the cumulative burden of natural disaster response on the nation’s military reservists.

The data reflect greater strain on the National Guard and show the potential stakes of the escalating conflict between states and President Donald Trump over use of the troops. Trump’s drive to deploy the National Guard in cities as an auxiliary law enforcement force—an effort curbed by a federal judge over the weekend—is playing out at a time when governors increasingly rely on reservists for disaster response.

In the legal battle over Trump’s efforts to deploy the National Guard in Portland, Oregon, that state’s attorney general, Dan Rayfield, argued in part that Democratic Gov. Tina Kotek needed to maintain control of the Guard in case they were needed to respond to wildfire—including a complex of fires now burning along the Rogue River in southwest Oregon.

The Trump administration, meanwhile, rejects the science showing that climate change is worsening natural disasters and has ceased Pentagon efforts to plan for such impacts or reduce its own carbon footprint.

The Department of Defense recently provided the natural disaster figures to four Democratic senators as part of a response to their query in March to Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth regarding planned cuts to the military’s climate programs. Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who led the query on behalf of herself and three other members of the Senate Committee on Armed Services, shared the response with Inside Climate News.

“The effects of climate change are destroying the military’s infrastructure—Secretary Hegseth should take that threat seriously,” Warren told ICN in an email. “This data shows just how costly this threat already is for the National Guard to respond to natural disasters. Failing to act will only make these costs skyrocket.”

Neither the Department of Defense nor the White House immediately responded to a request for comment.

Last week, Hegseth doubled down on his vow to erase climate change from the military’s agenda. “No more climate change worship,” Hegseth exhorted, before an audience of senior officials he summoned to Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia on October 1. “No more division, distraction, or gender delusions. No more debris,” he said. Departing from the prepared text released by the Pentagon, he added, “As I’ve said before, and will say again, we are done with that shit.”

But the data released by the Pentagon suggest that the impacts of climate change are shaping the military’s duties, even if the department ceases acknowledging the science or planning for a warming future. In 2024, National Guard paid duty days on disaster response—445,306—had nearly tripled compared to nine years earlier, with significant fluctuations in between. (The Pentagon provided the figures in terms of “mandays,” or paid duty days over and above reservists’ required annual training days.)

Demand for reservist deployment on disaster assistance over those years peaked at 1.25 million duty days in 2017, when Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria unleashed havoc in Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico.

The greatest deployment of National Guard members in response to wildfire over the past decade came in 2023, when wind-driven wildfires tore across Maui, leaving more than 100 people dead. Called into action by Gov. Josh Green, the Hawaii National Guard performed aerial water drops in CH-47 Chinook helicopters. On the ground, they helped escort fleeing residents, aided in search and recovery, distributed potable water, and performed other tasks.

Sen. Mazie Hirono of Hawaii, Sen. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut, and Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois joined Warren in seeking numbers on National Guard natural disaster deployment from the Pentagon.

It was not immediately possible to compare National Guard disaster deployment over the last decade to prior decades, since the Pentagon has not published a similar accounting for years prior to 2015.

But last year, a study by the Rand Corporation, a research firm, on stressors for the National Guard said that service leaders believed that natural disaster response missions were growing in scale and intensity.

“Seasons for these events are lasting longer, the extent of areas that are seeing these events is bigger, and the storms that occur are seemingly more intense and therefore more destructive,” noted the Rand study, produced for the Pentagon. “Because of the population density changes that have occurred, the devastation that can result and the population that can be affected are bigger as well.”

A history of the National Guard published by the Pentagon in 2001 describes the 1990s as a turning point for the service, marked by increasing domestic missions in part to “a nearly continuous string” of natural disasters.

One of those disasters was Hurricane Andrew, which ripped across southern Florida on August 23, 1992, causing more property damage than any storm in US history to that point. The crisis led to conflict between President George H.W. Bush’s administration and Florida’s Democratic governor, Lawton Chiles, over control of the National Guard and who should bear the blame for a lackluster initial response.

The National Guard, with 430,000 civilian soldiers, is a unique military branch that serves under both state and federal command. In Iraq and Afghanistan, for example, the president called on reservists to serve alongside the active-duty military. But state governors typically are commanders-in-chief for Guard units, calling on them in domestic crises, including natural disasters. The president only has limited legal authority to deploy the National Guard domestically, and such powers nearly always have been used in coordination with state governors.

But Trump has broken that norm and tested the boundaries of the law. In June, he deployed the National Guard for law and immigration enforcement in Los Angeles in defiance of Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom. (Trump also deployed the Guard in Washington, DC, where members already are under the president’s command.) Over the weekend, Trump’s plans to deploy the Guard in Portland, Oregon, were put on hold by US District Judge Karin J. Immergut, a Trump appointee. She issued a second, broader stay on Sunday to block Trump from an attempt to deploy California National Guard members to Oregon. Nevertheless, the White House moved forward with an effort to deploy the Guard to Chicago in defiance of Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker, a Democrat. In that case, Trump is calling on Guard members from a politically friendly state, Texas, and a federal judge has rejected a bid by both the city of Chicago and the state of Illinois to block the move.

The conflicts could escalate should a natural disaster occur in a state where Trump has called the Guard into service on law enforcement, one expert noted.

“At the end of the day, it’s a political problem,” said Mark Nevitt, a professor at Emory University School of Law and a Navy veteran who specializes in the national security implications of climate change. “If, God forbid, there’s a massive wildfire in Oregon and there’s 2,000 National Guard men and women who are federalized, the governor would have to go hat-in-hand to President Trump” to get permission to redeploy the service members for disaster response, he said.

“The state and the federal government, most times it works—they are aligned,” Nevitt said. “But you can imagine a world where the president essentially refuses to give up the National Guard because he feels as though the crime-fighting mission has primacy over whatever other mission the governor wants.”

That scenario may already be unfolding in Oregon. On September 27, the same day that Trump announced his intent to send the National Guard into Portland, Kotek was mobilizing state resources to fight the Moon Complex Fire on the Rogue River, which had tripled in size due to dry winds. That fire is now 20,000 acres and only 10 percent contained. Pointing to that fire, Oregon Attorney General Rayfield told the court the Guard should remain ready to respond if needed, noting the role reservists played in responding to major Oregon fires in 2017 and 2020.

“Wildfire response is one of the most significant functions the Oregon National Guard performs in the State,” Rayfield argued in a court filing Sunday.

Although Oregon won a temporary stay, the Trump administration is appealing that order. And given the increasing role of the National Guard in natural disaster response, according to the Pentagon’s figures, the legal battle will have implications far beyond Portland. It will determine whether governors like Kotek will be forced to negotiate with Trump for control of the National Guard amid a crisis that his administration is seeking to downplay.

Natural disasters are a rising burden for the National Guard Read More »