161 years ago, a New Zealand sheep farmer predicted AI doom

The text anticipated several modern AI safety concerns, including the possibility of machine consciousness, self-replication, and humans losing control of their technological creations. These themes later appeared in works like Isaac Asimov’s The Evitable Conflict, Frank Herbert’s Dune novels (Butler possibly served as the inspiration for the term “Butlerian Jihad“), and the Matrix films.

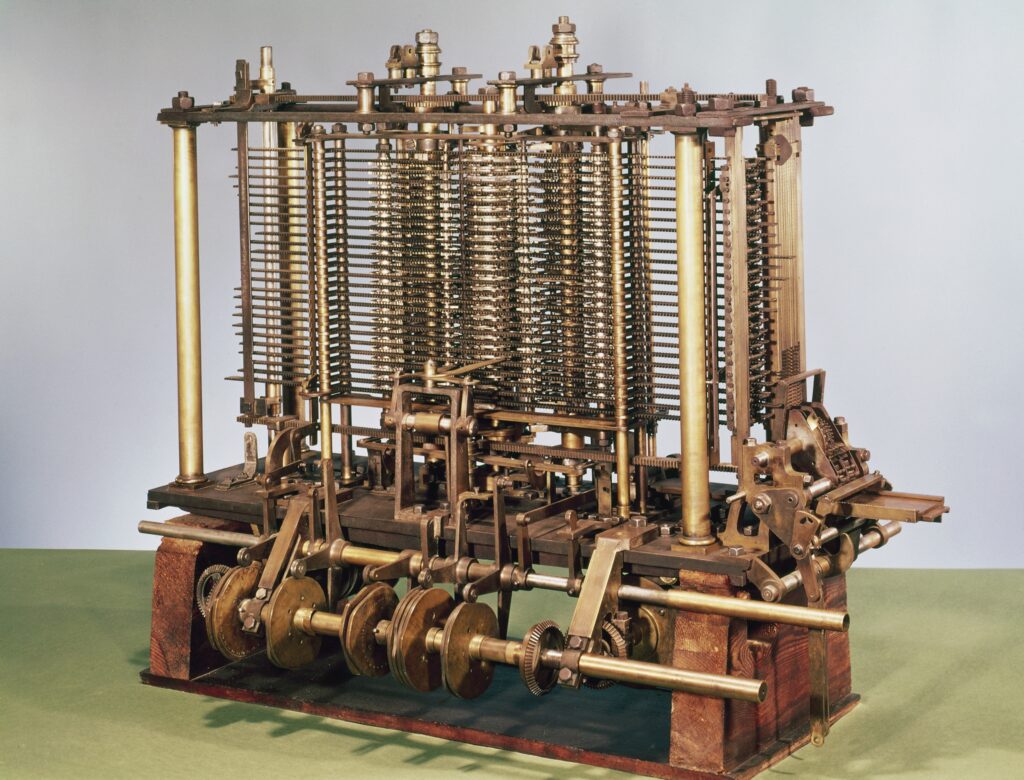

A model of Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, a calculating machine invented in 1837 but never built during Babbage’s lifetime. Credit: DE AGOSTINI PICTURE LIBRARY via Getty Images

Butler’s letter dug deep into the taxonomy of machine evolution, discussing mechanical “genera and sub-genera” and pointing to examples like how watches had evolved from “cumbrous clocks of the thirteenth century”—suggesting that, like some early vertebrates, mechanical species might get smaller as they became more sophisticated. He expanded these ideas in his 1872 novel Erewhon, which depicted a society that had banned most mechanical inventions. In his fictional society, citizens destroyed all machines invented within the previous 300 years.

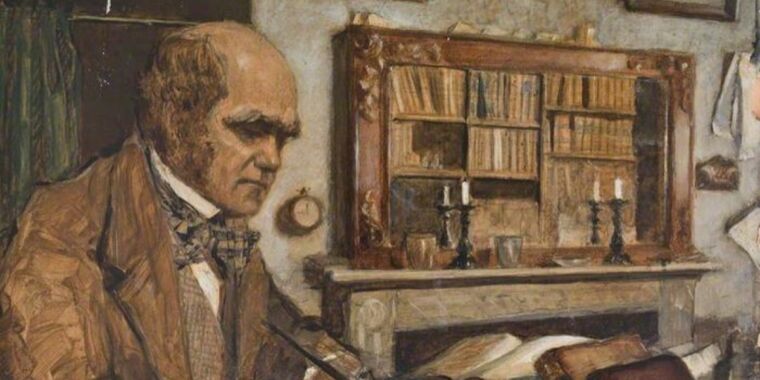

Butler’s concerns about machine evolution received mixed reactions, according to Butler in the preface to the second edition of Erewhon. Some reviewers, he said, interpreted his work as an attempt to satirize Darwin’s evolutionary theory, though Butler denied this. In a letter to Darwin in 1865, Butler expressed his deep appreciation for The Origin of Species, writing that it “thoroughly fascinated” him and explained that he had defended Darwin’s theory against critics in New Zealand’s press.

What makes Butler’s vision particularly remarkable is that he was writing in a vastly different technological context when computing devices barely existed. While Charles Babbage had proposed his theoretical Analytical Engine in 1837—a mechanical computer using gears and levers that was never built in his lifetime—the most advanced calculating devices of 1863 were little more than mechanical calculators and slide rules.

Butler extrapolated from the simple machines of the Industrial Revolution, where mechanical automation was transforming manufacturing, but nothing resembling modern computers existed. The first working program-controlled computer wouldn’t appear for another 70 years, making his predictions of machine intelligence strikingly prescient.

Some things never change

The debate Butler started continues today. Two years ago, the world grappled with what one might call the “great AI takeover scare of 2023.” OpenAI’s GPT-4 had just been released, and researchers evaluated its “power-seeking behavior,” echoing concerns about potential self-replication and autonomous decision-making.

161 years ago, a New Zealand sheep farmer predicted AI doom Read More »