Microsoft lays out its path to useful quantum computing

Its platform needs error correction that works with different hardware.

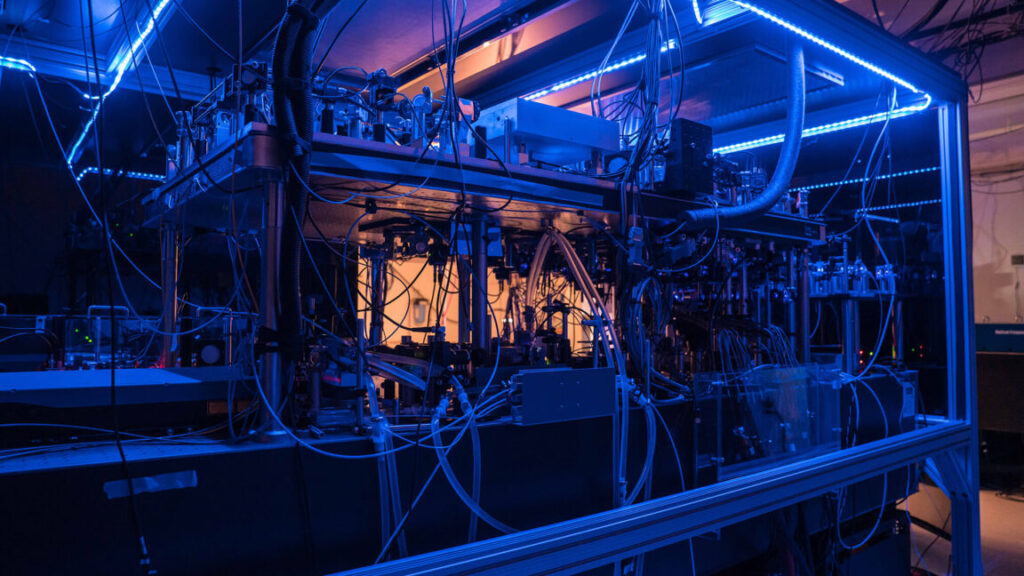

Some of the optical hardware needed to make Atom Computing’s machines work. Credit: Atom Computing

On Thursday, Microsoft’s Azure Quantum group announced that it has settled on a plan for getting error correction on quantum computers. While the company pursues its own hardware efforts, the Azure team is a platform provider that currently gives access to several distinct types of hardware qubits. So it has chosen a scheme that is suitable for several different quantum computing technologies (notably excluding its own). The company estimates that the system it has settled on can take hardware qubits with an error rate of about 1 in 1,000 and use them to build logical qubits where errors are instead 1 in 1 million.

While it’s describing the scheme in terms of mathematical proofs and simulations, it hasn’t shown that it works using actual hardware yet. But one of its partners, Atom Computing, is accompanying the announcement with a description of how its machine is capable of performing all the operations that will be needed.

Arbitrary connections

There are similarities and differences between what the company is talking about today and IBM’s recent update of its roadmap, which described another path to error-resistant quantum computing. In IBM’s case, it makes both the software stack that will perform the error correction and the hardware needed to implement it. It uses chip-based hardware, with the connections among qubits mediated by wiring that’s laid out when the chip is fabricated. Since error correction schemes require a very specific layout of connections among qubits, once IBM decides on a quantum error correction scheme, it can design chips with the wiring needed to implement that scheme.

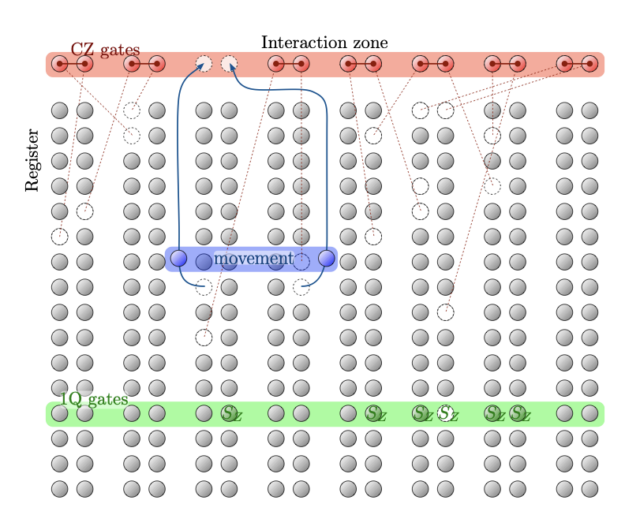

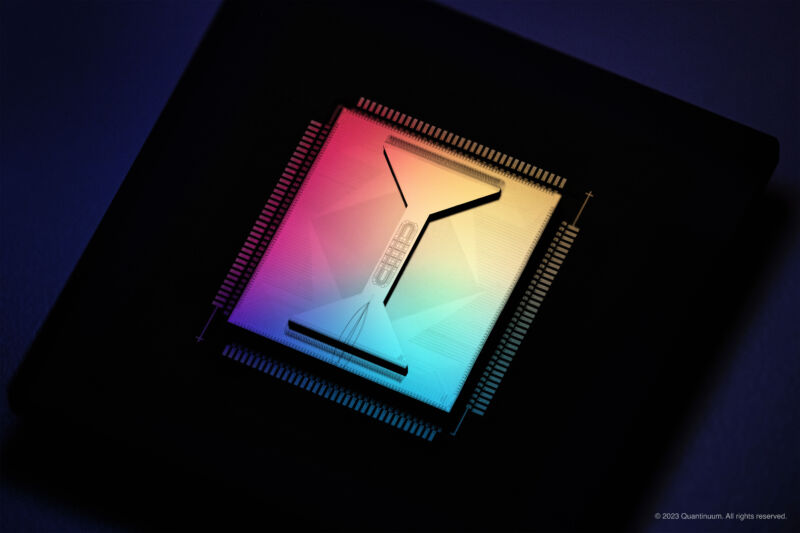

Microsoft’s Azure, in contrast, provides its users with access to hardware from several different quantum computing companies, each based on different technology. Some of them, like Rigetti and Microsoft’s own planned processor, are similar to IBM’s in that they have a fixed layout during manufacturing, and so can only handle codes that are compatible with their wiring layout. But others, such as those provided by Quantinuum and Atom Computing, store their qubits in atoms that can be moved around and connected in arbitrary ways. Those arbitrary connections allow very different types of error correction schemes to be considered.

It can be helpful to think of this using an analogy to geometry. A chip is like a plane, where it’s easiest to form the connections needed for error correction among neighboring qubits; longer connections are possible, but not as easy. Things like trapped ions and atoms provide a higher-dimensional system where far more complicated patterns of connections are possible. (Again, this is an analogy. IBM is using three-dimensional wiring in its processing chips, while Atom Computing stores all its atoms in a single plane.)

Microsoft’s announcement is focused on the sorts of processors that can form the more complicated, arbitrary connections. And, well, it’s taking full advantage of that, building an error correction system with connections that form a four-dimensional hypercube. “We really have focused on the four-dimensional codes due to their amenability to current and near term hardware designs,” Microsoft’s Krysta Svore told Ars.

The code not only describes the layout of the qubits and their connections, but also the purpose of each hardware qubit. Some of them are used to hang on to the value of the logical qubit(s) stored in a single block of code. Others are used for what are called “weak measurements.” These measurements tell us something about the state of the ones that are holding on to the data—not enough to know their values (a measurement that would end the entanglement), but enough to tell if something has changed. The details of the measurement allow corrections to be made that restore the original value.

Microsoft’s error correction system is described in a preprint that the company recently released. It includes a family of related geometries, each of which provides different degrees of error correction, based on how many simultaneous errors they can identify and fix. The descriptions are about what you’d expect for complicated math and geometry—”Given a lattice Λ with an HNF L, the code subspace of the 4D geometric code CΛ is spanned by the second homology H2(T4Λ,F2) of the 4-torus T4Λ—but the gist is that all of them convert collections of physical qubits into six logical qubits that can be error corrected.

The more hardware qubits you add to host those six logical qubits, the greater error protection each of them gets. That becomes important because some more sophisticated algorithms will need more than the one-in-a-million error protection that Svore said Microsoft’s favored version will provide. That favorite is what’s called the Hadamard version, which bundles 96 hardware qubits to form six logical qubits, and has a distance of eight (distance being a measure of how many simultaneous errors it can tolerate). You can compare that with IBM’s announcement, which used 144 hardware qubits to host 12 logical qubits at a distance of 12 (so, more hardware, but more logical qubits and greater error resistance).

The other good stuff

On its own, a description of the geometry is not especially exciting. But Microsoft argues that this family of error correction codes has a couple of significant advantages. “All of these codes in this family are what we call single shot,” Svore said. “And that means that, with a very low constant number of rounds of getting information about the noise, one can decode and correct the errors. This is not true of all codes.”

Limiting the number of measurements needed to detect errors is important. For starters, measurements themselves can create errors, so making fewer makes the system more robust. In addition, in things like neutral atom computers, the atoms have to be moved to specific locations where measurements take place, and the measurements heat them up so that they can’t be reused until cooled. So, limiting the measurements needed can be very important for the performance of the hardware.

The second advantage of this scheme, as described in the draft paper, is the fact that you can perform all the operations needed for quantum computing on the logical qubits these schemes host. Just like in regular computers, all the complicated calculations performed on a quantum computer are built up from a small number of simple logical operations. But not every possible logical operation works well with any given error correction scheme. So it can be non-trivial to show that an error correction scheme is compatible with enough of the small operations to enable universal quantum computation.

So, the paper describes how some logical operations can be performed relatively easily, while a few others require manipulations of the error correction scheme in order to work. (These manipulations have names like lattice surgery and magic state distillation, which are good signs that the field doesn’t take itself that seriously.)

So, in sum, Microsoft feels that it has identified an error correction scheme that is fairly compact, can be implemented efficiently on hardware that stores qubits in photons, atoms, or trapped ions, and enables universal computation. What it hasn’t done, however, is show that it actually works. And that’s because it simply doesn’t have the hardware right now. Azure is offering trapped ion machines from IonQ and Qantinuum, but these top out at 56 qubits—well below the 96 needed for their favored version of these 4D codes. The largest it has access to is a 100-qubit machine from a company called PASQAL, which barely fits the 96 qubits needed, leaving no room for error.

While it should be possible to test smaller versions of codes in the same family, the Azure team has already demonstrated its ability to work with error correction codes based on hypercubes, so it’s unclear whether there’s anything to gain from that approach.

More atoms

Instead, it appears to be waiting for another partner, Atom Computing, to field its next-generation machine, one it’s designing in partnership with Microsoft. “This first generation that we are building together between Atom Computing and Microsoft will include state-of-the-art quantum capabilities, will have 1,200 physical qubits,” Svore said “And then the next upgrade of that machine will have upwards of 10,000. And so you’re looking at then being able to go to upwards of a hundred logical qubits with deeper and more reliable computation available. “

So, today’s announcement was accompanied by an update on progress from Atom Computing, focusing on a process called “midcircuit measurement.” Normally, during quantum computing algorithms, you have to resist performing any measurements of the value of qubits until the entire calculation is complete. That’s because quantum calculations depend on things like entanglement and each qubit being in a superposition between its two values; measurements can cause all that to collapse, producing definitive values and ending entanglement.

Quantum error correction schemes, however, require that some of the hardware qubits undergo weak measurements multiple times while the computation is in progress. Those are quantum measurements taking place in the middle of a computation—midcircuit measurements, in other words. To show that its hardware will be up to the task that Microsoft expects of it, the company decided to demonstrate mid-circuit measurements on qubits implementing a simple error correction code.

The process reveals a couple of notable features that are distinct from doing this with neutral atoms. To begin with, the atoms being used for error correction have to be moved to a location—the measurement zone—where they can be measured without disturbing anything else. Then, the measurement typically heats up the atom slightly, meaning they have to be cooled back down afterward. Neither of these processes is perfect, and so sometimes an atom gets lost and needs to be replaced with one from a reservoir of spares. Finally, the atom’s value needs to be reset, and it has to be sent back to its place in the logical qubit.

Testing revealed that about 1 percent of the atoms get lost each cycle, but the system successfully replaces them. In fact, they set up a system where the entire collection of atoms is imaged during the measurement cycle, and any atom that goes missing is identified by an automated system and replaced.

Overall, without all these systems in place, the fidelity of a qubit is about 98 percent in this hardware. With error correction turned on, even this simple logical qubit saw its fidelity rise over 99.5 percent. All of which suggests their next computer should be up to some significant tests of Microsoft’s error correction scheme.

Waiting for the lasers

The key questions are when it will be released, and when its successor, which should be capable of performing some real calculations, will follow it? That’s something that’s a challenging question to ask because, more so than some other quantum computing technologies, neutral atom computing is dependent on something that’s not made by the people who build the computers: lasers. Everything about this system—holding atoms in place, moving them around, measuring, performing manipulations—is done with a laser. The lower the noise of the laser (in terms of things like frequency drift and energy fluctuations), the better performance it’ll have.

So, while Atom can explain its needs to its suppliers and work with them to get things done, it has less control over its fate than some other companies in this space.

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.

Microsoft lays out its path to useful quantum computing Read More »