There was enough governance related news this week to spin it out.

Anthropic, Google, OpenAI, Mistral, Aleph Alpha, Cohere and others commit to signing the EU AI Code of Practice. Google has now signed. Microsoft says it is likely to sign.

xAI signed the AI safety chapter of the code, but is refusing to sign the others, citing them as overreach especially as pertains to copyright.

The only company that said it would not sign at all is Meta.

This was the underreported story. All the important AI companies other than Meta have gotten behind the safety section of the EU AI Code of Practice. This represents a considerable strengthening of their commitments, and introduces an enforcement mechanism. Even Anthropic will be forced to step up parts of their game.

That leaves Meta as the rogue state defector that once again gives zero anythings about safety, as in whether we all die, and also safety in its more mundane forms. Lol, we are Meta, indeed. So the question is, what are we going to do about it?

xAI took a middle position. I see the safety chapter as by far the most important, so as long as xAI is signing that and taking it seriously, great. Refusing the other parts is a strange flex, and I don’t know exactly what their problem is since they didn’t explain. They simply called it ‘unworkable,’ which is odd when Google, OpenAI and Anthropic all declared they found it workable.

Then again, xAI finds a lot of things unworkable. Could be a skill issue.

This is a sleeper development that could end up being a big deal. When I say ‘against regulations’ I do not mean against AI regulations. I mean against all ‘regulations’ in general, no matter what, straight up.

From the folks who brought you ‘figure out who we technically have the ability to fire and then fire all of them, and if something breaks maybe hire them back, this is the Elon way, no seriously’ and also ‘whoops we misread something so we cancelled PEPFAR and a whole lot of people are going to die,’ Doge is proud to give you ‘if a regulation is not technically required by law it must be an unbridled bad thing we can therefore remove, I wonder why they put up this fence.’

Hannah Natanson, Jeff Stein, Dan Diamond and Rachel Siegel (WaPo): The tool, called the “DOGE AI Deregulation Decision Tool,” is supposed to analyze roughly 200,000 federal regulations to determine which can be eliminated because they are no longer required by law, according to a PowerPoint presentation obtained by The Post that is dated July 1 and outlines DOGE’s plans.

Roughly 100,000 of those rules would be deemed worthy of trimming, the PowerPoint estimates — mostly through the automated tool with some staff feedback. The PowerPoint also suggests the AI tool will save the United States trillions of dollars by reducing compliance requirements, slashing the federal budget and unlocking unspecified “external investment.”

The conflation here is absolute. There are two categories of regulations: The half ‘required by law,’ and the half ‘worthy of trimming.’ Think of the trillions you can save.

They then try to hedge and claim that’s not how it is going to work.

Asked about the AI-fueled deregulation, White House spokesman Harrison Fields wrote in an email that “all options are being explored” to achieve the president’s goal of deregulating government.

…

No decisions have been completed on using AI to slash regulations, a HUD spokesperson said.

…

The spokesperson continued: “The intent of the developments is not to replace the judgment, discretion and expertise of staff but be additive to the process.”

That would be nice. I’m far more ‘we would be better off with a lot less regulations’ than most. I think it’s great to have an AI tool that splits off the half we can consider cutting from the half we are stuck with. I still think that ‘cut everything that a judge wouldn’t outright reverse if you tried cutting it’ is not a good strategy.

I find the ‘no we will totally consider whether this is a good idea’ talk rather hollow, both because of track record and also they keep telling us what the plan is?

“The White House wants us higher on the leader board,” said one of the three people. “But you have to have staff and time to write the deregulatory notices, and we don’t. That’s a big reason for the holdup.”

…

That’s where the AI tool comes in, the PowerPoint proposes. The tool will save 93 percent of the human labor involved by reviewing up to 500,000 comments submitted by the public in response to proposed rule changes. By the end of the deregulation exercise, humans will have spent just a few hours to cancel each of the 100,000 regulations, the PowerPoint claims.

They then close by pointing out that the AI makes mistakes even on the technical level it is addressing. Well, yeah.

Also, welcome to the future of journalism:

China has its own AI Action Plan and is calling for international cooperation on AI. Wait, what do they mean by that? If you look in the press, that depends who you ask. All the news organizations will be like ‘the Chinese released an AI Action Plan’ and then not link to the actual plan, I had to have o3 dig it up.

Here’s o3’s translation of the actual text. This is almost all general gestures in the direction of capabilities, diffusion, infrastructure and calls for open models. It definitely is not an AI Action Plan in the sense that America offered an AI Action Plan, with had lots of specific actionable proposals. This is more of a general outline of a plan and statement of goals, at best. At least it doesn’t talk about or call for a ‘race’ but a call for everything to be open and accelerated is not obviously better.

-

Seize AI opportunities together. Governments, international organizations, businesses, research institutes, civil groups, and individuals should actively cooperate, accelerate digital‑infrastructure build‑out, explore frontier AI technologies, and spread AI applications worldwide, fully unlocking AI’s power to drive growth, achieve the UN‑2030 goals, and tackle global challenges.

-

Foster AI‑driven innovation. Uphold openness and sharing, encourage bold experimentation, build international S‑and‑T cooperation platforms, harmonize policy and regulation, and remove technical barriers to spur continuous breakthroughs and deep “AI +” applications.

-

Empower every sector. Deploy AI across manufacturing, consumer services, commerce, healthcare, education, agriculture, poverty reduction, autonomous driving, smart cities, and more; share infrastructure and best practices to supercharge the real economy.

-

Accelerate digital infrastructure. Expand clean‑energy grids, next‑gen networks, intelligent compute, and data centers; create interoperable AI infrastructure and unified compute‑power standards; support especially the Global South in accessing and applying AI.

-

Build a pluralistic open‑source ecosystem. Promote cross‑border open‑source communities and secure platforms, open technical resources and interfaces, improve compatibility, and let non‑sensitive tech flow freely.

-

Supply high‑quality data. Enable lawful, orderly, cross‑border data flows; co‑create top‑tier datasets while safeguarding privacy, boosting corpus diversity, and eliminating bias to protect cultural and ecosystem diversity.

-

Tackle energy and environmental impacts. Champion “sustainable AI,” set AI energy‑ and water‑efficiency standards, promote low‑power chips and efficient algorithms, and scale AI solutions for green transition, climate action, and biodiversity.

-

Forge standards and norms. Through ITU, ISO, IEC, and industry, speed up standards on safety, industry, and ethics; fight algorithmic bias and keep standards inclusive and interoperable.

-

Lead with public‑sector adoption. Governments should pioneer reliable AI in public services (health, education, transport), run regular safety audits, respect IP, enforce privacy, and explore lawful data‑trading mechanisms to upgrade governance.

-

Govern AI safety. Run timely risk assessments, create a widely accepted safety framework, adopt graded management, share threat intelligence, tighten data‑security across the pipeline, raise explainability and traceability, and prevent misuse.

-

Implement the Global Digital Compact. Use the UN as the main channel, aim to close the digital divide—especially for the Global South—and quickly launch an International AI Scientific Panel and a Global AI Governance Dialogue under UN auspices.

-

Boost global capacity‑building. Through joint labs, shared testing, training, industry matchmaking, and high‑quality datasets, help developing countries enhance AI innovation, application, and governance while improving public AI literacy, especially for women and children.

-

Create inclusive, multi‑stakeholder governance. Establish public‑interest platforms involving all actors; let AI firms share use‑case lessons; support think tanks and forums in sustaining global technical‑policy dialogue among researchers, developers, and regulators.

What does it have to say about safety or dealing with downsides? We have ‘forge standards and norms’ with a generic call for safety and ethics standards, which seems to mostly be about interoperability and ‘bias.’

Mainly we have ‘Govern AI safety,’ which is directionally nice to see I guess but essentially content free and shows no sign that the problems are being taken seriously on the levels we care about. Most concretely, in the ninth point, we have a call for regular safety audits of AI models. That all sounds like ‘the least you could do.’

Here’s one interpretation of the statement:

Brenda Goh (Reuters): China said on Saturday it wanted to create an organisation to foster global cooperation on artificial intelligence, positioning itself as an alternative to the U.S. as the two vie for influence over the transformative technology.

…

Li did not name the United States but appeared to refer to Washington’s efforts to stymie China’s advances in AI, warning that the technology risked becoming the “exclusive game” of a few countries and companies.

China wants AI to be openly shared and for all countries and companies to have equal rights to use it, Li said, adding that Beijing was willing to share its development experience and products with other countries, particularly the “Global South”. The Global South refers to developing, emerging or lower-income countries, mostly in the southern hemisphere.

…

The foreign ministry released online an action plan for global AI governance, inviting governments, international organisations, enterprises and research institutions to work together and promote international exchanges including through a cross-border open source community.

As in, we notice you are ahead in AI, and that’s not fair. You should do everything in the open so you let us catch up in all the ways you are ahead, so we can bury you using the ways in which you are behind. That’s not an unreasonable interpretation.

Here’s another.

The Guardian: Chinese premier Li Qiang has proposed establishing an organisation to foster global cooperation on artificial intelligence, calling on countries to coordinate on the development and security of the fast-evolving technology, days after the US unveiled plans to deregulate the industry.

…

Li warned Saturday that artificial intelligence development must be weighed against the security risks, saying global consensus was urgently needed.

…

“The risks and challenges brought by artificial intelligence have drawn widespread attention … How to find a balance between development and security urgently requires further consensus from the entire society,” the premier said.

Li said China would “actively promote” the development of open-source AI, adding Beijing was willing to share advances with other countries, particularly developing ones in the global south.

So that’s a call to keep security in mind, but every concrete reference is mundane and deals with misuse, and then they call for putting everything out into the open, with the main highlighted ‘risk’ to coordinate on being that America might get an advantage, and encouraging us to give it away via open models to ‘safeguard multilateralism.’

A third here, from the Japan Times, frames it as a call for an alliance to take aim at an American AI monopoly.

Director Michael Kratsios: China’s just-released AI Action Plan has a section that drives at a fundamental difference between our approaches to AI: whether the public or private sector should lead in AI innovation.

I like America’s odds of success.

He quotes point nine, which his translation has as ‘the public sector takes the lead in deploying applications.’ Whereas o3’s translation says ‘governments should pioneer reliable AI in public services (health, education, transport), run regular safety audits, respect IP, enforce privacy, and explore lawful data‑trading mechanisms to upgrade governance.’

Even in Michael’s preferred translation, this is saying government should aggressively deploy AI applications to improve government services. The American AI Action Plan, correctly, fully agrees with this. Nothing in the Chinese statement says to hold the private sector back. Quite the contrary.

The actual disagreement we have with point nine is the rest of it, where the Chinese think we should run regular safety audits, respect IP and enforce privacy. Those are not parts of the American AI Action Plan. Do you think we were right not to include those provisions, sir? If so, why?

Suppose in the future, we learned we were in a lot more danger than we think we are in now, and we did want to make a deal with China and others. Right now the two sides would be very far apart but circumstances could quickly change that.

Could we do it in a way that could be verified?

It wouldn’t be easy, but we do have tools.

This is the sort of thing we should absolutely be preparing to be able to do, whether or not we ultimately decide to do it.

Mauricio Baker: For the last year, my team produced the most technically detailed overview so far. Our RAND working paper finds: strong verification is possible—but we need ML and hardware research.

You can find the paper here and on arXiv. It includes a 5-page summary and a list of open challenges.

In the Cold War, the US and USSR used inspections and satellites to verify nuclear weapon limits. If future, powerful AI threatens to escape control or endanger national security, the US and China would both be better off with guardrails.

It’s a tough challenge:

– Verify narrow restrictions, like “no frontier AI training past some capability,” or “no mass-deploying if tests show unacceptable danger”

– Catch major state efforts to cheat

– Preserve confidentiality of models, data, and algorithms

– Keep overhead low

Still, reasons for optimism:

– No need to monitor all computers—frontier AI needs thousands of specialized AI chips.

– We can build redundant layers of verification. A cheater only needs to be caught once.

– We can draw from great work in cryptography and ML/hardware security.

One approach is to use existing chip security features like Confidential Computing, built to securely verify chip activities. But we’d need serious design vetting, teardowns, and maybe redesigns before the US could strongly trust Huawei’s chip security (or frankly, NVIDIA’s).

“Off-chip” mechanisms could be reliable sooner: network taps or analog sensors (vetted, limited use, tamper evident) retrofitted onto AI data centers. Then, mutually secured, airgapped clusters could check if claimed compute uses are reproducible and consistent with sensor data.

Add approaches “simple enough to work”: whistleblower programs, interviews of personnel, and intelligence activities. Whistleblower programs could involve regular in-person contact—carefully set up so employees can anonymously reveal violations, but not much more.

…

We could have an arsenal of tried-and-tested methods to confidentially verify a US-China AI treaty. But at the current pace, in three years, we’ll just have a few speculative options. We need ML and hardware researchers, new RFPs by funders, and AI company pilot programs.

Jeffrey Ladish: Love seeing this kind of in-depth work on AI treaty verification. A key fact is verification doesn’t have to be bullet proof to be useful. We can ratchet up increasingly robust technical solutions while using other forms of HUMINT and SIGINT to provide some level of assurance.

Remember, the AI race is a mixed-motive conflict, per Schelling. Both sides have an incentive to seek an advantage, but also have an incentive to avoid mutually awful outcomes. Like with nuclear war, everyone loses if any side loses control of superhuman AI.

This makes coordination easier, because even if both sides don’t like or trust each other, they have an incentive to cooperate to avoid extremely bad outcomes.

It may turn out that even with real efforts there are not good technical solutions. But I think it is far more likely that we don’t find the technical solutions due to lack of trying, rather than that the problem is so hard that it cannot be done.

The reaction to the AI Action Plan was almost universally positive, including here from Nvidia and AMD. My own review, focused on the concrete proposals within, also reflected this. It far exceeded my expectations on essentially all fronts, so much so that I would be actively happy to see most of its proposals implemented rather than nothing be done.

I and others focused on the concrete policy, and especially concrete policy relative to expectations and what was possible in context, for which it gets high praise.

But a document like this might have a lot of its impact due to the rhetoric instead, even if it lacks legal force, or cause people to endorse the approach as ideal in absolute terms rather than being the best that could be done at the time.

So, for example, the actual proposals for open models were almost reasonable, but if the takeaway is lots more rhetoric of ‘yay open models’ like it is in this WSJ editorial, where the central theme is very clearly ‘we must beat China, nothing else matters, this plan helps beat China, so the plan is good’ then that’s really bad.

Another important example: Nothing in the policy proposals here makes future international cooperation harder. The rhetoric? A completely different story.

The same WSJ article also noticed the same obvious contradictions with other Trump policies that I did – throttling renewable energy and high-skilled immigration and even visas are incompatible with our goals here, the focus on ‘woke AI’ could have been much worse but remains a distraction, also I would add, what is up with massive cuts to STEM research if we are taking this seriously? If we are serious about winning and worry that one false move would ‘forfeit the race’ then we need to act like it.

Of course, none of that is up to the people who were writing the AI Action Plan.

What the WSJ editorial board didn’t notice, or mention at all, is the possibility that there are other risks or downsides at play here, and it dismisses outright the possibility of any form of coordination or cooperation. That’s a very wrong, dangerous and harmful attitude, one it shares with many in or lobbying the government.

A worry I have on reflection, that I wasn’t focusing on at the time, is that officials and others might treat the endorsements of the good policy proposals here as an endorsement of the overall plan presented by the rhetoric, especially the rhetoric at the top of the plan, or of the plan’s sufficiency and that it is okay to ignore and not speak about what the plan ignores and does not speak about.

That rhetoric was alarmingly (but unsurprisingly) terrible, as it is the general administration plan of emphasizing whenever possible that we are in an ‘AI race’ that will likely go straight to AGI and superintelligence even if those words couldn’t themselves be used in the plan, where ‘winning’ is measured in the mostly irrelevant ‘market share.’

And indeed, the inability to mention AGI or superintelligence in the plan leads to such exactly the standard David Sacks lines that toxically center the situation on ‘winning the race’ by ‘exporting the American tech stack.’

I will keep repeating, if necessary until I am blue in the face, that this is effectively a call (the motivations for which I do not care to speculate) for sacrificing the future and get us all killed in order to maximize Nvidia’s market share.

There is no ‘tech stack’ in the meaningful sense of necessary integration. You can run any most any AI model on most any advanced chip, and switch on an hour’s notice.

It does not matter who built the chips. It matters who runs the chips and for whose benefit. Supply is constrained by manufacturing capacity, so every chip we sell is one less chip we have. The idea that failure to hand over large percentages of the top AI chips to various authoritarians, or even selling H20s directly to China as they currently plan to do, would ‘forfeit’ ‘the race’ is beyond absurd.

Indeed, both the rhetoric and actions discussed here do the exact opposite. It puts pressure on others especially China to push harder towards ‘the race’ including the part that counts, the one to AGI, and also the race for diffusion and AI’s benefits. And the chips we sell arm China and others to do this important racing.

There is later talk acknowledging that ‘we do not intend to ignore the risks of this revolutionary technological power.’ But Sacks frames this as entire about the risk that AI will be misused or stolen by malicious actors. Which is certainly a danger, but far from the primary thing to worry about.

That’s what happens when you are forced to pretend AGI, ASI, potential loss of control and all other existential risks do not exist as possibilities. The good news is that there are some steps in the actual concrete plan to start preparing for those problems, even if they are insufficient and it can’t be explained, but it’s a rough path trying to sustain even that level of responsibility under this kind of rhetorical oppression.

The vibes and rhetoric were accelerationist throughout, especially at the top, and completely ignored the risks and downsides of AI, and the dangers of embracing a rhetoric based on an ‘AI race’ that we ‘must win,’ and where that winning mostly means chip market share. Going down this path is quite likely to get us all killed.

I am happy to make the trade of allowing the rhetoric to be optimistic, and to present the Glorious Transhumanist Future as likely to be great even as we have no idea how to stay alive and in control while getting there, so long as we can still agree to take the actions we need to take in order to tackle that staying alive and in control bit – again, the actions are mostly the same even if you are highly optimistic that it will work out.

But if you dismiss the important dangers entirely, then your chances get much worse.

So I want to be very clear that I hate that rhetoric, I think it is no good, very bad rhetoric both in terms of what is present and what (often with good local reasons) is missing, while reiterating that the concrete particular policy proposals were as good as we could reasonably have hoped for on the margin, and the authors did as well as they could plausibly have done with people like Sacks acting as veto points.

That includes the actions on ‘preventing Woke AI,’ which have convinced even Sacks to frame this as preventing companies from intentionally building DEI into their models. That’s fine, I wouldn’t want that either.

Even outlets like Transformer weighed in positively, with them calling the plan ‘surprisingly okay’ and noting its ability to get consensus support, while ignoring the rhetoric. They correctly note the plan is very much not adequate. It was a missed opportunity to talk about or do something about various risks (although I understand why), and there was much that could have been done that wasn’t.

Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh: Crazy to reflect on the three global AI competitions going on right now:

– 1. US political leadership have made AI a prestige race, echoing the Space Race. It’s cool and important and strategic, and they’re going to Win.

– 2. For Chinese leadership AI is part of economic strength, soft power and influence. Technology is shared, developing economies will be built on Chinese fundamental tech, the Chinese economy and trade relations will grow. Weakening trust in a capricious US is an easy opportunity to take advantage of.

– 3. The AGI companies are racing something they think will out-think humans across the board, that they don’t yet know how to control, and think might literally kill everyone.

Scariest of all is that it’s not at all clear to decision-makers that these three things are happening in parallel. They think they’re playing the same game, but they’re not.

I would modify the US political leadership position. I think to a lot of them it’s literally about market share, primarily chip market share. I believe this because they keep saying, with great vigor, that it is literally about chip market share. But yes, they think this matters because of prestige, and because this is how you get power.

My guess is, mostly:

-

The AGI companies understand these are three distinct things.

-

They are using the confusions of political leadership for their own ends.

-

The Chinese understand there are two distinct things, but not three.

-

As in, they know what US leadership is doing, and they know what they are doing, and they know these are distinct things.

-

They do not feel the AGI and understand its implications.

-

The bulk of the American political class cannot differentiate between the US and Chinese strategies, or strategic positions, or chooses to pretend not to, cannot imagine things other than ordinary prestige, power and money, and cannot feel the AGI.

-

There are those within the power structure who do feel the AGI, to varying extents, and are trying to sculpt actions (including the action plan) accordingly with mixed success.

-

An increasing number of them, although still small, do feel the AGI to varying extents but have yet to cash that out into anything except ‘oh ’.

-

There is of course a fourth race or competition, which is to figure out how to build it without everyone dying.

The actions one would take in each of these competitions are often very similar, especially the first three and often the fourth as well, but sometimes are very different. What frustrates me most is when there is an action that is wise on all levels, yet we still don’t do it.

Also, on the ‘preventing Woke AI’ question, the way the plan and order are worded seems designed to make compliance easy and not onerous, but given other signs from the Trump administration lately, I think we have reason to worry…

Fact Post: Trump’s FCC Chair says he will put a “bias monitor” in place who will “report directly” to Trump as part of the deal for Sky Dance to acquire CBS.

Ari Drennen: The term that the Soviet Union used for this job was “apparatchik” btw.

I was willing to believe that firing Colbert was primarily a business decision. This is very different imagine the headline in reverse: “Harris’s FCC Chair says she will put a “bias monitor” in place who will “report directly” to Harris as part of the deal for Sky Dance to acquire CBS.”

Now imagine it is 2029, and the headline is ‘AOC appoints new bias monitor for CBS.’ Now imagine it was FOX. Yeah. Maybe don’t go down this road?

Director Krastios has now given us his view on the AI Action Plan. This is a chance to see how much it is viewed as terrible rhetoric versus its good policy details, and to what extent overall policy is going to be guided by good details versus terrible rhetoric.

Peter Wildeford offers his takeaway summary.

Peter Wildeford: Winning the Global AI Race

-

The administration’s core philosophy is a direct repudiation of the previous one, which Kratsios claims was a “fear-driven” policy “manically obsessed” with hypothetical risks that stifled innovation.

-

The plan is explicitly called an “Action Plan” to signal a focus on immediate execution and tangible results, not another government strategy document that just lists aspirational goals.

-

The global AI race requires America to show the world a viable, pro-innovation path for AI development that serves as an alternative to the EU’s precautionary, regulation-first model.

He leads with hyperbolic slander, which is par for the course, but yes concrete action plans are highly useful and the EU can go too far in its regulations.

There are kind of two ways to go with this.

-

You could label any attempt to do anything to ensure we don’t die as ‘fear-driven’ and ‘maniacally obsessed’ with ‘hypothetical’ risks that ‘stifle’ innovation, and thus you probably die.

-

You could label the EU and Biden Administration as ‘fear-driven’ and ‘manically obsessed’ with ‘hypothetical’ risks that ‘stifle’ innovation, contrasting that with your superior approach, and then having paid this homage do reasonable things.

The AI Action Plan as written was the second one. But you have to do that on purpose, because the default outcome is to shift to the first one.

Executing the ‘American Stack’ Export Strategy

-

The strategy is designed to prevent a scenario where the world runs on an adversary’s AI stack by proactively offering a superior, integrated American alternative.

-

The plan aims to make it simple for foreign governments to buy American by promoting a “turnkey solution”—combining chips, cloud, models, and applications—to reduce complexity for the buyer.

-

A key action is to reorient US development-finance institutions like the DFC and EXIM to prioritize financing for the export of the American AI stack, shifting their focus from traditional hard infrastructure.

The whole ‘export’ strategy is either nonsensical, or an attempt to control capital flow, because I heard a rumor that it is good to be the ones directing capital flow.

Once again, the ‘tech stack’ thing is not, as described here, what’s the word? Real.

The ‘adversary’ does not have a ‘tech stack’ to offer, they have open models people can run on the same chips. They don’t have meaningful chips to even run their own operations, let alone export. And the ‘tech’ does not ‘stack’ in a meaningful way.

Turnkey solutions and package marketing are real. I don’t see any reason for our government to be so utterly obsessed with them, or even involved at all. That’s called marketing and serving the customer. Capitalism solves this. Microsoft and Amazon and Google and OpenAI and Anthropic and so on can and do handle it.

Why do we suddenly think the government needs to be prioritizing financing this? Given that it includes chip exports, how is it different from ‘traditional hard infrastructure’? Why do we need financing for the rest of this illusory stack when it is actually software? Shouldn’t we still be focusing on ‘traditional hard infrastructure’ in the places we want it, and then whenever possible exporting the inference?

Refining National Security Controls

-

Kratsios argues the biggest issue with export controls is not the rules themselves but the lack of resources for enforcement, which is why the plan calls for giving the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) the tools it needs.

-

The strategy is to maintain strict controls on the most advanced chips and critical semiconductor-manufacturing components, while allowing sales of less-advanced chips under a strict licensing regime.

-

The administration is less concerned with physical smuggling of hardware and more focused on preventing PRC front companies from using legally exported hardware for large-scale, easily flaggable training runs.

-

Proposed safeguards against misuse are stringent “Know Your Customer” (KYC) requirements paired with active monitoring for the scale and scope of compute jobs.

It is great to see the emphasis on enforcement. It is great to hear that the export control rules are not the issue.

In which case, can we stop waving them, such as with H20 sales to China? Thank you. There is of course a level at which chips can be safely sold even directly to China, but the experts all agree the H20 is past that level.

The lack of concern about smuggling is a blind eye in the face of overwhelming evidence of widespread smuggling. I don’t much care if they are claiming to be concerned, I care about the actual enforcement, but we need enforcement. Yes, we should stop ‘easily flaggable’ PRC training runs and use KYC techniques, but this is saying we should look for our keys under the streetlight and then if we don’t find the keys assume we can start our car without them.

Championing ‘Light-Touch’ Domestic Regulation

-

The administration rejects the idea of a single, overarching AI law, arguing that expert agencies like the FDA and DOT should regulate AI within their specific domains.

-

The president’s position is that a “patchwork of regulations” across 50 states is unacceptable because the compliance burden disproportionately harms innovative startups.

-

While using executive levers to discourage state-level rules, the administration acknowledges that a durable solution requires an act of Congress to create a uniform federal standard.

Yes, a ‘uniform federal standard’ would be great, except they have no intention of even pretending to meaningfully pursue one. They want each federal agency to do its thing in its own domain, as in a ‘use case’ based AI regime which when done on its own is the EU approach and doomed to failure.

I do acknowledge the step down from ‘kill state attempts to touch anything AI’ (aka the insane moratorium) to ‘discourage’ state-level rules using ‘executive levers,’ at which point we are talking price. One worries the price will get rather extreme.

Addressing AI’s Economic Impact at Home

-

Kratsios highlights that the biggest immediate labor need is for roles like electricians to build data centers, prompting a plan to retrain Americans for high-paying infrastructure jobs.

-

The technology is seen as a major productivity tool that provides critical leverage for small businesses to scale and overcome hiring challenges.

-

The administration issued a specific executive order on K-12 AI education to ensure America’s students are prepared to wield these tools in their future careers.

Ahem, immigration, ahem, also these things rarely work, but okay, sure, fine.

Prioritizing Practical Infrastructure Over Hypothetical Risk

-

Kratsios asserts that chip supply is no longer a major constraint; the key barriers to the AI build-out are shortages of skilled labor and regulatory delays in permitting.

-

Success will be measured by reducing the time from permit application to “shovels in the ground” for new power plants and data centers.

-

The former AI Safety Institute is being repurposed to focus on the hard science of metrology—developing technical standards for measuring and evaluating models, rather than vague notions of “safety.”

It is not the only constraint, but it is simply false to say that chip supply is no longer a major constraint.

Defining success in infrastructure in this way would, if taken seriously, lead to large distortions in the usual obvious Goodhart’s Law ways. I am going to give the benefit of the doubt and presume this ‘success’ definition is local, confined to infrastructure.

If the only thing America’s former AISI can now do are formal measured technical standards, then that is at least a useful thing that it can hopefully do well, but yeah it basically rules out at the conceptual level the idea of actually addressing the most important safety issues, by dismissing them are ‘vague.’

This goes beyond ‘that which is measured is managed’ to an open plan of ‘that which is not measured is not managed, it isn’t even real.’ Guess how that turns out.

Defining the Legislative Agenda

-

While the executive branch has little power here, Kratsios identifies the use of copyrighted data in model training as a “quite controversial” area that Congress may need to address.

-

The administration would welcome legislation that provides statutory cover for the reformed, standards-focused mission of the Center for AI Standards and Innovation (CAISI).

-

Continued congressional action is needed for appropriations to fund critical AI-related R&D across agencies like the National Science Foundation.

TechCrunch: 20 national security experts urge Trump administration to restrict Nvidia H20 sales to China.

The letter says the H20 is a potent accelerator of China’s frontier AI capabilities and could be used to strengthen China’s military.

Americans for Responsible Innovation: The H20 and the AI models it supports will be deployed by China’s PLA. Under Beijing’s “Military-Civil Fusion” strategy, it’s a guarantee that H20 chips will be swiftly adapted for military purposes. This is not a question of trade. It is a question of national security.

It would be bad enough if this was about selling the existing stock of H20s, that Nvidia has taken a writedown on, even though it could easily sell them in the West instead. It is another thing entirely that Nvidia is using its capacity on TSMC machines to make more of them, choosing to create chips to sell directly to China instead of creating chips for us.

Ruby Scanlon: Nvidia placed orders for 300,000 H20 chipsets with contract manufacturer TSMC last week, two sources said, with one of them adding that strong Chinese demand had led the US firm to change its mind about just relying on its existing stockpile.

It sounds like we’re planning on feeding what would have been our AI chips to China. And then maybe you should start crying? Or better yet tell them they can’t do it?

I share Peter Wildeford’s bafflement here:

Peter Wildeford: “China is close to catching up to the US in AI so we should sell them Nvidia chips so they can catch up even faster.”

I never understand this argument from Nvidia.

The argument is also false, Nvidia is lying, but I don’t understand even if it were true.

There is only a 50% premium to buy Nvidia B200 systems within China, which suggests quite a lot of smuggling is going on.

Tao Burga: Nvidia still insists that there’s “no evidence of any AI chip diversion.” Laughable. All while lobbying against the data center chip location verification software that would provide the evidence. Tell me, where does the $1bn [in AI chips smuggled to China] go?

Rob Wiblin: Nvidia successfully campaigning to get its most powerful AI chips into China has such “the capitalists will sell us the rope with which we will hang them” energy.

Various people I follow keep emphasizing that China is smuggling really a lot of advanced AI chips, including B200s and such, and perhaps we should be trying to do something about it, because it seems rather important.

Chipmakers will always oppose any proposal to track chips or otherwise crack down on smuggling and call it ‘burdensome,’ where the ‘burden’ is ‘if you did this they would not be able to smuggle as many chips, and thus we would make less money.’

Reuters Business: Demand in China has begun surging for a business that, in theory, shouldn’t exist: the repair of advanced v artificial intelligence chipsets that the US has banned the export of to its trade and tech rival.

Peter Wildeford: Nvidia position: “datacenters from smuggled products is a losing proposition […] Datacenters require service and support, which we provide only to authorized NVIDIA products.”

Reality: Nvidia AI chip repair industry booms in China for banned products.

Scott Bessent Warns TSMC’s $40 billion Arizona fab that could meet 7% of American chip demand keeps getting delayed, and blames inspectors and red tape. There’s confusion here in the headline that he is warning it would ‘only’ meet 7% of demand, but 7% of demand would be amazing for one plant and the article’s text reflects this.

Bessent criticized regulatory hurdles slowing construction of the $40 billion facility. “Evidently, these chip design plants are moving so quickly, you’re constantly calling an audible and you’ve got someone saying, ‘Well, you said the pipe was going to be there, not there. We’re shutting you down,’” he explained.

It does also mean that if we want to meet 100% or more of demand we will need a lot more plants, but we knew that.

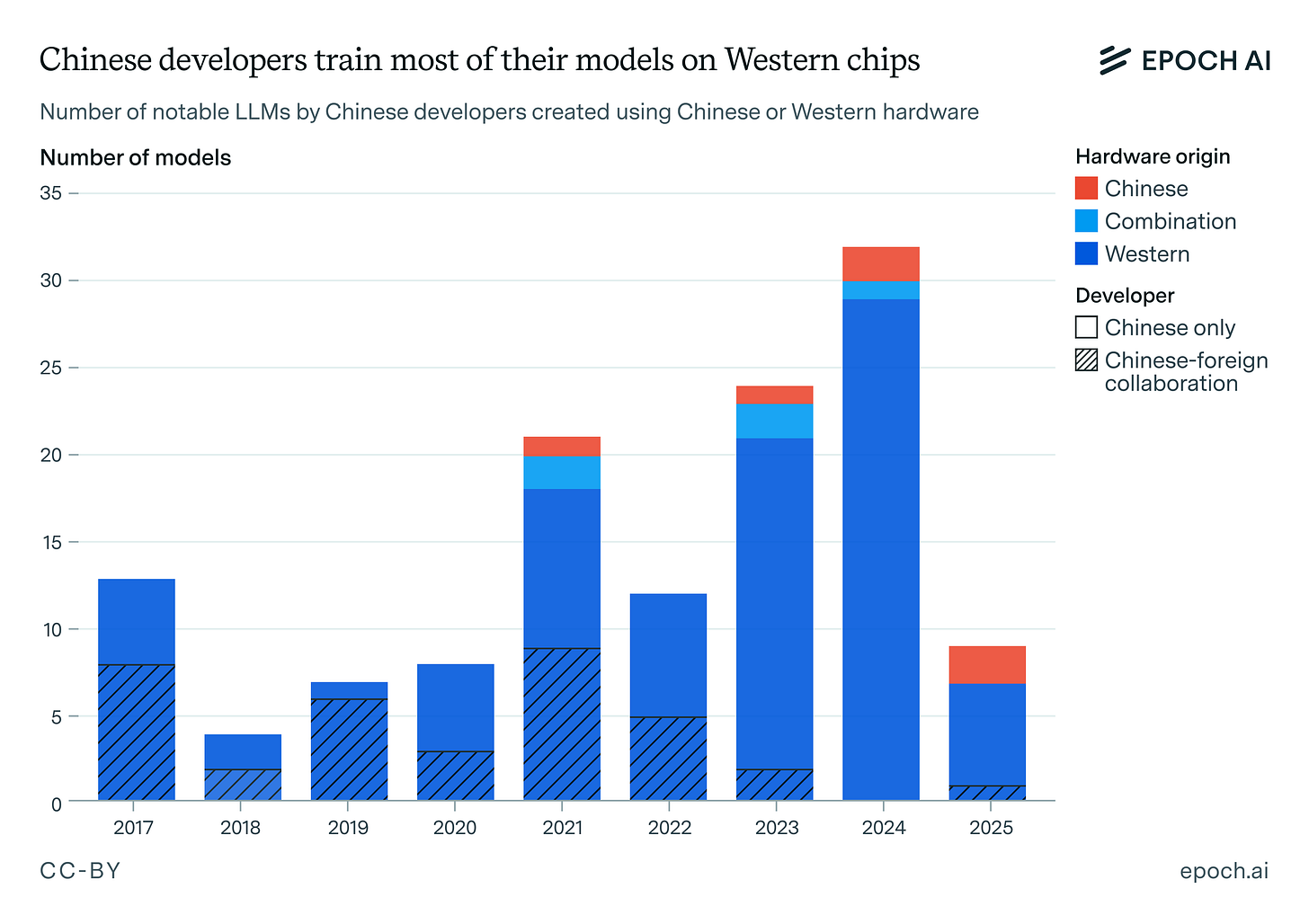

Epoch reports that Chinese hardware is behind American hardware, and is ‘closing the gap’ but faces major obstacles in chip manufacturing capability.

Epoch: Even if we exclude joint ventures with U.S., Australian, or U.K. institutions (where the developers can access foreign silicon), the clear majority of homegrown models relied on NVIDIA GPUs. In fact, it took until January 2024 for the first large language model to reportedly be trained entirely on Chinese hardware, arguably years after the first large language models.

…

Probably the most important reason for the dominance of Western hardware is that China has been unable to manufacture these AI chips in adequate volumes. Whereas Huawei reportedly manufactured 200,000 Ascend 910B chips in 2024, estimates suggest that roughly one million NVIDIA GPUs were legally delivered to China in the same year.

That’s right. For every top level Huawei chip manufactured, Nvidia sold five to China. No, China is not about to export a ‘full Chinese tech stack’ for free the moment we turn our backs. They’re offering downloads of r1 and Kimi K2, to be run on our chips, and they use all their own chips internally because they still have a huge shortage.

Put bluntly, we don’t see China leaping ahead on compute within the next few years. Not only would China need to overcome major obstacles in chip manufacturing and software ecosystems, they would also need to surpass foreign companies making massive investments into hardware R&D and chip fabrication.

Unless export controls erode or Beijing solves multiple technological challenges in record time, we think that China will remain at least one generation behind in hardware. This doesn’t prevent Chinese developers from training and running frontier AI models, but it does make it much more costly.

Overall, we think these costs are large enough to put China at a substantial disadvantage in AI scaling for at least the rest of the decade.

Beating China may or may not be your number one priority. We do know that taking export controls seriously is the number one priority for ‘beating China.’

Intel will cancel 14A and following nodes, essentially abandoning the technological frontier, if it cannot win a major external customer.