Would a universal basic income (UBI) work? What would it do?

Many people agree July’s RCT on giving people a guaranteed income, and its paper from Eva Vivalt, Elizabeth Rhodes, Alexander W. Bartik, David E. Broockman and Sarah Miller was, despite whatever flaws it might have, the best data we have so far on the potential impact of UBI. There are many key differences from how UBI would look if applied for real, but this is the best data we have.

This study was primarily funded by Sam Altman, so whatever else he may be up to, good job there. I do note that my model of ‘Altman several years ago’ is more positive than mine of Altman now, and past actions like this are a lot of the reason I give him so much benefit of the doubt.

They do not agree on what conclusions we should draw. This is not a simple ‘UBI is great’ or ‘UBI it does nothing.’

I see essentially four responses.

-

The first group says this shows UBI doesn’t work. That’s going too far. I think the paper greatly reduces the plausibility of the best scenarios, but I don’t think it rules UBI out as a strategy, especially if it is a substitute for other transfers.

-

The second group says this was a disappointing result for UBI. That UBI could still make sense as a form of progressive redistribution, but likely at a cost of less productivity so long as people impacted are still productive. I agree.

-

The third group did its best to spin this into a positive result. There was a lot of spin here, and use of anecdotes, and arguments as soldiers. Often these people were being very clear they were true believers and advocates, that want UBI now, and were seeking the bright side. Respect? There were some bright spots that they pointed out, and no one study over three years should make you give up, but this was what it was and I wish people wouldn’t spin like that.

-

The fourth group was some mix of ‘if brute force (aka money) doesn’t solve your problem you’re not using enough’ and also ‘but work is bad, actually, and leisure is good.’ That if we aren’t getting people not to work then the system is not functioning, or that $1k/month wasn’t enough to get the good effects, or both. I am willing to take a bold ‘people working more is mostly good’ stance, for the moment, although AI could change that. And while I do think that a more permanent or larger support amount would do some interesting things, I wouldn’t expect to suddenly see polarity reverse.

I am so dedicated to actually reading this paper that it cost me $5. Free academia now.

Core design was that there were 1,000 low-income individuals randomized into getting $1k/month for 3 years, or $36k total. A control group of 2,000 others got $50/month, or $1800 total. Average household income in the study before transfers was $29,900.

They then studied what happened.

Before looking at the results, what are the key differences between this and UBI?

Like all studies of UBI, this can only be done for a limited population, and it only lasts a limited amount of time.

If you tell me I am getting $1,000/month for life, then that makes me radically richer, and also radically safer. In extremis you can plan to live off that, or it can be a full fallback. Which is a large part of the point, and a lot of the danger as well.

If instead you give me that money for only three years, then I am slightly less than $36k richer. Which is nice, but impacts my long term prospects much less. It is still a good test of the ‘give people money’ hypothesis but less good at testing UBI.

The temporary form, and also the limited scope, means that it won’t cause a cultural shift and changing of norms. Those changes might be good or bad, and they could overshadow other impacts.

Does this move towards a cultural norm of taking big risks, learning new things and investing, or investing in niche value production that doesn’t monetize as well? Or does it become acceptable to lounge around playing video games? Do people use it to have more kids, or do people think ‘if I don’t have kids I never have to work’? And so on. The long term and short term effects could be very different.

Also key is that you don’t see the impact of the cost on inflation or the budget. If you gave out a UBI you would have to pay for it somehow, either printing money or collecting taxes or borrowing. Here you get to measure the upside without the downside. Alternatively, we also aren’t replacing the rest of the welfare state.

John Arnold: Fundamental problem with so-called UBI pilots and why @Arnold_Ventures has never funded one is they don’t actually test that. They test LFBI (Lucky Few Basic Income), a program that is not inflationary. Pilots can’t evaluate the general equilibrium effects when everyone gets $.

Ernie Tedeschi: Good point. They also can’t test (unless they’re considerably well-funded and credible) how people change their long-run behavior because they trust that a UBI program will be stable, reliable, and persistent over their entire lives.

John Arnold: Agree. My hunch is that it would need to be at least 5 years in duration, maybe much longer, to get a good sense as to behavior change. Knowing that you will get $1k/month for 3 years is different than believing you will get it for life.

And in this study, the people getting the money improve their relative status, not only their absolute position.

We can still learn a lot. I would treat this as a very good test of ‘give people money.’ It seems less strong as strictly a test of UBI, since many of the long term or equilibrium effects won’t happen.

This was a very good and well-executed study, including great response rates (96%+).

Here are the findings that stood out to me, some but not all from the abstract:

For every one dollar received, total household income excluding the transfers fell by ‘at least 21 cents,’ and total individual income fell by at least 12 cents or $1,500/year.

The fall in transfer income of $4,100/year matters a lot if you’re Giving People Money privately. That wipes out a third of gains. For government it is presumably a wash.

There was a 2% decrease in labor force participation and 1.4 hour/week reduction in labor hours, and a similar amount by partners, a 4%-5% overall decline in income. Later they say there was a 2.2 hour/week decline per household, a 4.6% decrease versus the mean. Those are different but the implications seem similar.

There was no improvement in workplace amenities, despite them trying hard to measure that. This suggests such amenities are not so highly valued by workers.

More time was spent on leisure, and to a lesser degree on transportation and finances.

No impact on quality of employment, ruling out even small improvements. Employment rate at baseline was 58%, with 17% having a second job.

20% had college degrees, 92% had finished high school or a GED or a post-secondary program by the endline, versus 92.8% for the treatment group, which is something, they say this was concentrated in the young and on GEDs.

Unemployment lasted 8.8 months in the treatment group versus 7.7 for controls. This is a sensible adjustment, if it is coming from a sensible base. There were ~0.3 additional months of unemployment per year for the treatment group. Section 5.3 says they were more likely to apply for and search for jobs, but they did so for fewer distinct jobs. As we all know essentially everyone underinvests in such searches, and fails to apply to enough distinct jobs while searching. Even I was guilty of this.

No significant effects on investments in human capital, except younger participants may pursue more formal education.

Those seem like sensible adjustments. You have more money, so you work a little less. Once you get reasonably on in years, pursuing more education becomes a hard sell.

Especially disappointing: “While treated participants exhibited more entrepreneurial orientation and intentions, this did not translate into significantly more entrepreneurial activity. The point estimate is positive, but small, and it is possible that very few people have the inclination to become entrepreneurs in general.”

Also bad news: “We find a significant increase in the likelihood that a respondent has a self-reported disability (an increase of 4.0 percentage points on a base of 31 percentage points in the control group) and in the likelihood they report a health problem or disability that limits the work they can do (an increase of 4.0 percentage points on a base of 28 percentage points in the control group) (Table 11).”

This is a remarkably high number, and it is some mix of way too many health problems and way too many incentives to claim to have them.

“Participants appear to spend approximately the full amount of the transfers each month, on average.” This is a mistake if they are not growing their permanent income, and implies they have social or cultural restrictions preventing them from saving. By the end they are at most a few thousand dollars wealthier than the control group.

This rules out a short term apocalypse. If you don’t count ‘clawbacks’ from the government, the transfer was mostly effective. That’s not bad, depending on how you pay for it. It depends what you were hoping to find, I suppose?

Also note that this study started during Covid. That could make the results not too representative of what would have happened at another time.

Transfers clawed back about a third of the money. Reducing hours worked did more of that, and high effective marginal tax rates in this zone doubtless contributed to that. What did we get for the money?

Before looking at the reactions of others, I would say not enough. There was an entire array of variables that changed very little. The group was given roughly an extra year’s income, and ended up in the same place as before. Study author Eva Vivalt agrees it is surprising that more things did not change.

The study did not make a real attempt to capture total consumer welfare, to see how much those who got money were happier and better off during the three year period. Certainly one can favor more redistribution on that basis. But you have to fund that somehow, and that seems unable to on its own justify the transfers, which must somehow be paid for. They did see declines in stress and food insecurity in year one, but they faded by year two, potentially in part because the end of the study loomed.

Here is a fun exercise: John Horton asked GPT-4o to complete the UBI experiment abstract and fill in the part that gives the results. Its predictions were for much better results in several areas. Claude gave a similar answer. In particular, both LLMs thought employment quality and stability and entrepreneurial activity would improve. This seems like confirmation that the result was bad news.

Eva Vivalt, lead author of this excellent study, has a good thread here going over many of the results. He is clearly struggling to find positive outcomes.

Eva Vivalt: But, it’s not all bad news.

One bright spot was entrepreneurship.

We see significant increases in what we pre-specified as “precursors” to entrepreneurial activity: entrepreneurial orientation and intention.

We find null effects for whether or not a participant started or helped to start a business, but entrepreneurship is not for everyone (hence pre-specifying that we’d also consider entrepreneurial orientation and intention, as they represent more common intermediate outcomes).

As noted above, you see the problem. What good are precursors without the thing they precurse? We see little if any impact on the actual amount of entrepreneurship.

Yes, there was more entrepreneurship in the ‘black and female’ category, but if the overall numbers aren’t up it is hard to find a positive overall read on the situation – is it actively negative for non-black males? Seems unlikely. If this is the good news, then there is little good news.

David Broockman, another author, also has a good thread on the study.

Everyone agrees this was a great and important paper and study, even when they view the results as highly negative for UBI. This is excellent work and excellent science. I would have loved to do this for 30 years instead of 3, but you do what you can.

Alex Tabarrok: Important thread on important paper.

tl/dr;

“You have to squint to find *anypositive effects other than people do more leisure when you give $”.

Kevin Bryan: Massive OpenResearch basic income papers are out (@smilleralert @dbroockman @evavivalt @AlexBartik @elizabethrds).

Very much worth reading – my view is that it is an incredible RCT and an incredible disappointment. RCT was USD11400/yr for 3 years, 1k treatment, 2k control.

The study was crazy, by the way. Very low attrition, time diaries, *blood draws to measure health*(?!) My favorite: they got Illinois to pass a law that this RCT income wasn’t taxable & didn’t change other-benefit eligibility. That is, it was a net post-tax increase in income!

Disappointment 1: Even though these are low-income people (avg household income 30k, so RCT is almost 40% increase in income!), treatment work hours fell 5% relative to control, and treatment household income only 6200, not 11600 higher than control.

…

What about other endpoints? Better job? No – and can rule out even small effects on job quality. More human capital training? No. Better *health*? No. And that’s even though experts the team surveyed thought there would be huge positive benefits!

…

You have to squint to find *anypositive effects other than “people do more leisure when you give $”. Treatment groups say they are more likely to consider entrepreneurship in the future. Some young folks in treatment report more education (though this doesn’t survive MHT).

This is *by farthe largest, low-income, developed country universal basic income trial, and by far the most rigorous. My posterior on how valuable UBI is compared to, say, expanded EITC and spending on early childhood has gone *waydown.

…

Final note: massive up to authors & funders. 50 million $ and years of hard work on a topic authors care deeply about, & instead of p hacking or pretending things went well, they were rigorous & honest about null results. Journalists: this is very rare and should be highlighted!

I do think this study scores a big one for Give Parents Money rather than Give People Money. The money seems to have a much bigger impact on children and families, while also raising fertility.

Ruxandra Teslo: This fits into my paradigm that culture beats policy more often than not, even when policy is very strong. Many people won’t like the results of this study. Change ain’t easy and is seldom executed via government mandates.

I agree change is not easy, but also a lot of the reason government mandates usually don’t work is that they are rarely well-designed or implemented. If we wanted a particular result (like entrepreneurship or education or fertility) then this was never going to be an efficient way to get at those. It still could plausibly have worked better than what we found.

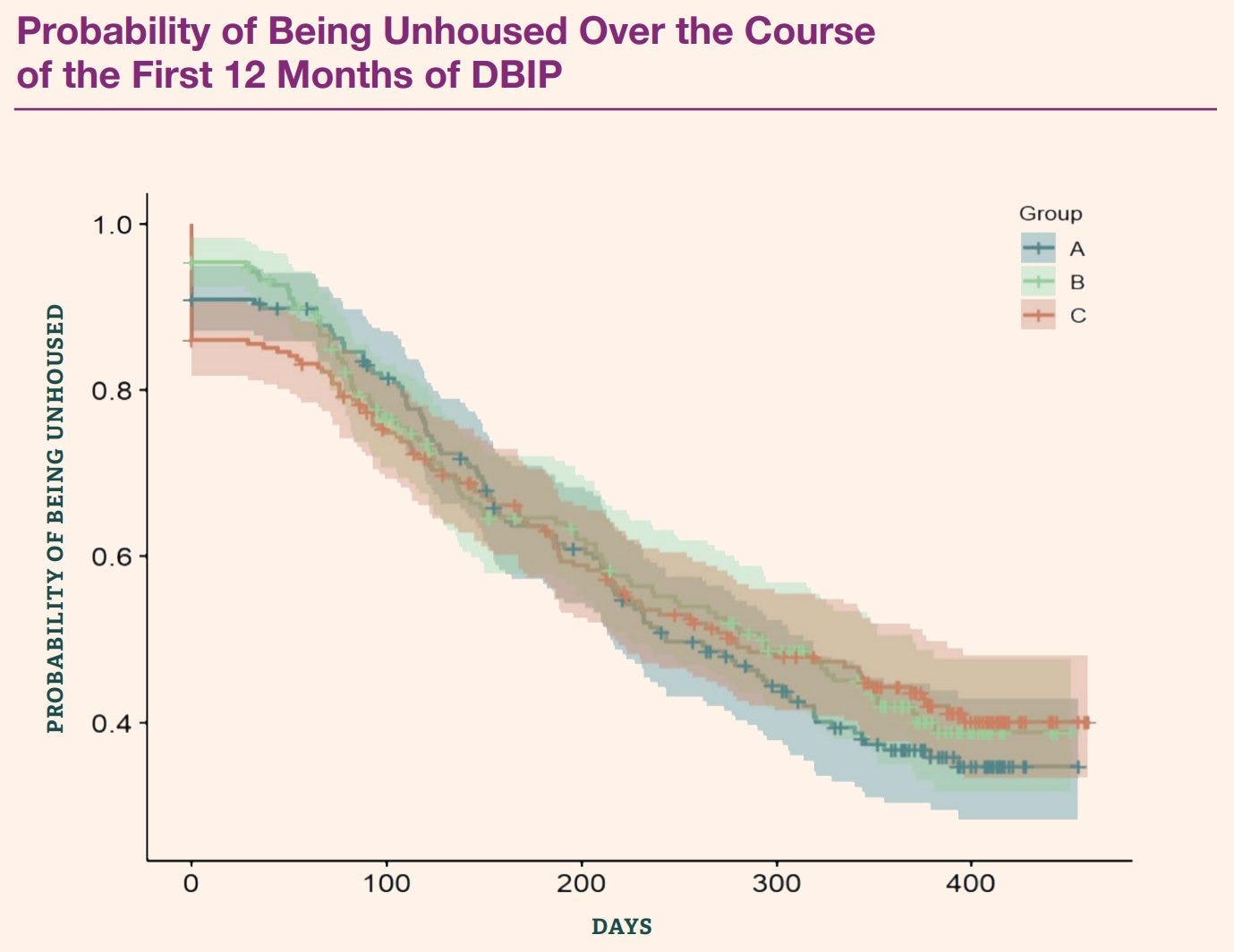

Maxwell Tabarrok talks about this study as well as three others. He summarizes this study’s result as a 20 percent decline in work and not much else happening besides more leisure. He also covers the Denver UBI trial (also $1k/month), which was exclusively in the homeless, and showed that the money didn’t even do much for actual homelessness there – people found housing often but you see almost the same results in the control group. This one still seems strange to me, and clearly surprised basically everyone – it essentially says that either you’re able to get off the streets anyway, or the money wasn’t enough.

Scott Santens is a strong advocate for UBI. He attempts to make the bull case. He says that declines in hours worked were not found in previous studies, and puts the relative decline in hours worked in the context of people in other countries (like in Europe) working far less, and that the group worked a lot more at the end of the study (in 2023 after Covid) than at the start (in 2020 during Covid, which he makes clear is the cause here).

He also notes that the disemployment effects were concentrated on single parents, and that various groups had no effect. That does make sense here, and he notes it mirrors prior results, but as always if you buy the division it means the effect is much larger in the impacted (here single parent) group. Given that the pilot was for ages 21-40 and the upper half of that age group did not see an impact, the hopeful case is that the 40+ group also would see little or no impact.

He tries to explain the decline in work we do see as a shift to education. I didn’t see enough actual increase in education to fully explain it, though? Perhaps I am not seeing how that math works out.

Another note was that most labor decrease was in the relatively high income group, not the low income group. I take his explanations to suggest that this group was effectively facing very high marginal tax rates. Indeed, this is the area where people plausibly face effective marginal tax rates approaching 100% when accounting for benefits. If you attempt to boost the income of someone caught in that trap, it makes sense they would respond by cutting back hours – one could investigate the details to see to what extent that was the pattern.

He repeats the ‘women and blacks started more businesses’ angle, but again are we then to believe that non-black males started fewer? On job search, he notes the increased length of job search in time but not the decreased intensity of the searches. On job quality he admits the results are disappointing but cites the anecdotes as telling a different story. I think that’s a clear case of spin or fooling oneself, of course you can find some stories that went well where the change was plausibly causal. Probably some people did long term plays, others slacked off or focused on family.

People were more likely to move especially to new neighborhoods, which I hadn’t noticed earlier, but I’m not convinced that is net good here. That seems plausibly like a frequently poor investment, unless it is moving to opportunity. I worry it’s moving to nicer places without a long term plan to also earn more.

I do think the big decreases in alcohol and drug use are a clear positive result. We have a 40%+ decrease in problematic drinking, an 81%+ decrease in non-prescribed painkillers. That’s great, but also we know the overall health numbers, and also overall hours worked, and so on. This should decompose into other benefits, so if this is real and you don’t see those benefits, it’s being counteracted elsewhere.

There’s talk about how ‘cash can be anything’ and citing all the things people spent their cash on. Well, yes, and I do buy the ‘better cash than in kind benefits’ argument.

I appreciated the detailed analysis and willingness to note details that were unsupportive, and not trying to disguise his advocacy. This was the right way to make a case like this. I did come out of it modestly more hopeful than I came in, as he found some good info I had overlooked, and he made good points on how this study differed from his proposed realistic scenario. But I found most of it to be a (honest) stretch.

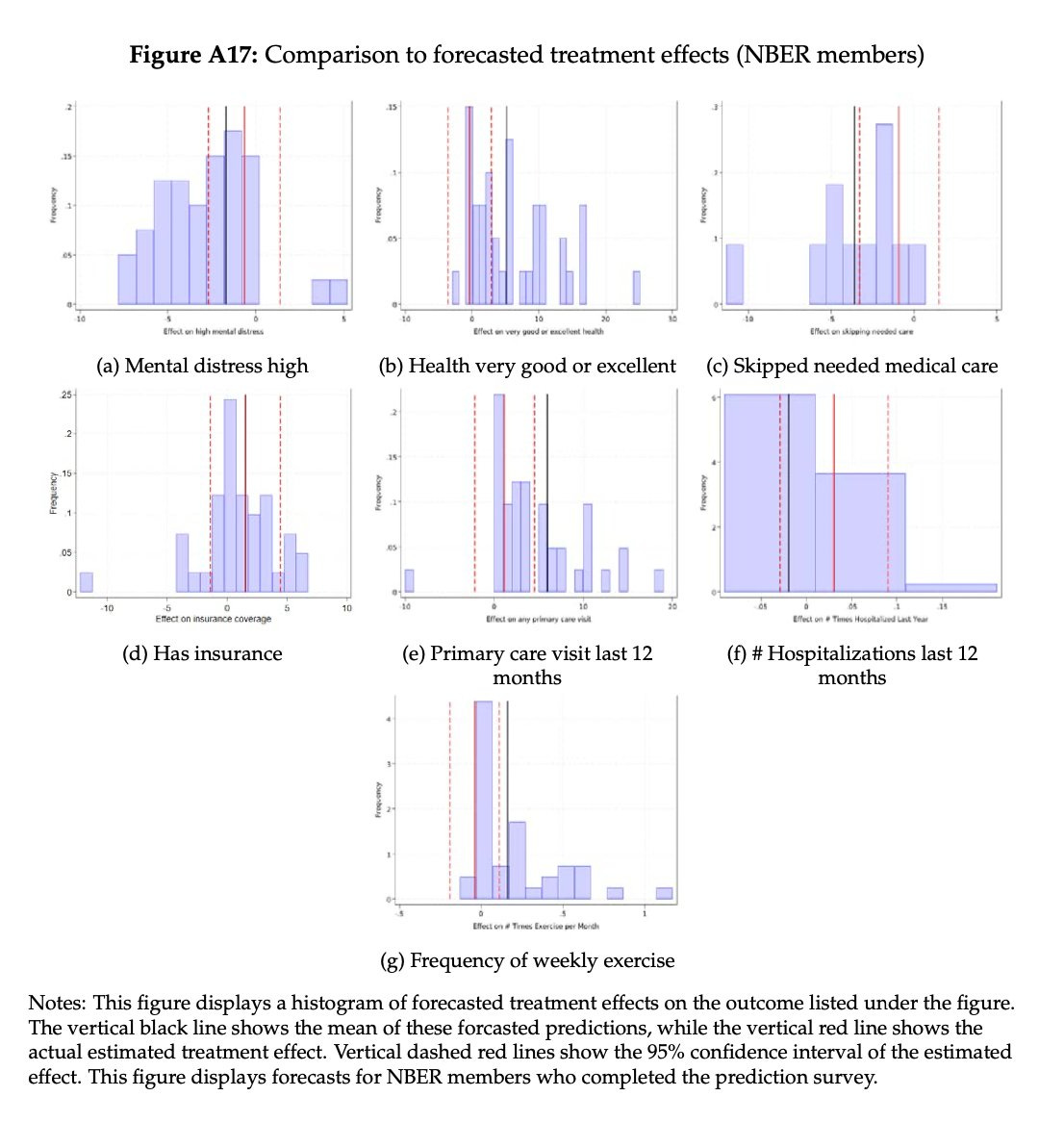

Another cool note is that the authors collected ex ante forecasts of what the researchers would find.

Eva Vivalt: So I can say that experts were reasonably accurate for labor supply (the magnitude of what we saw at endline is higher but it’s within the confidence intervals) but inaccurate for other employment outcomes, e.g., they were overoptimistic about education and the wage rate.

Key differences:

-

Prediction was increase in hourly wage, actual effect was -$0.23/hr at endline.

-

Prediction was searching for work less, result was looking more by the endline.

-

Prediction was more secondary education (2.5%-4.5%) versus no found effect.

This confirms the study results were disappointing.

Rob Wiblin asks, is it so bad or surprising that the money mostly went to consumption? The answer is, it’s not stunning, but the effects were worse than expected in many areas, and we were hoping to get other positive effects and less negative effects along with the consumption.

The decrease in work is no surprise – the issue is what we got in exchange.

Noah Smith: Another disappointing result for basic income. Unlike some earlier, smaller studies, this big RCT finds a significant disemployment effect. Even just $1000 per month causes some people to stop working, or to work less.

Alex Howlett: This is not disappointing. It’s exactly what we should expect. If Universal Basic Income doesn’t cause people to work less, then we haven’t set the amount high enough.

Well, yes, and I do think Noah Smith was jumping to conclusions there. We should indeed expect people to work less when given money. Along with ‘giving people money costs money’ that is the key downside of redistribution and progressive taxation.

If you say ‘people working is bad and we should want them to do less of that’ then I am going to disagree. Yes, if the amount of production could be held constant while people worked less, that would be great, we should do that. But we should presume that the jobs in question are productive.

The deal is, we spend money and we reduce the amount of production and work. In exchange, the people who get the benefits, well, benefit. They are better off. This is some combination of them being better off for themselves, them getting to invest and become more productive and beneficial for society (including having more children and investing more in those children), and buying their support for a stable and prosperous civilization.

You want to spend less, impact quantity of working hours less, and get more other benefits. Instead, we found more impact on work (although not a catastrophic amount), and little other benefits. And that’s terrible.

In extremis, you can have scenarios where Giving People Money leads to investment, and that investment increases productivity or frees up time and human capital, such that you end up with more production, or even with more time spent on work. This is especially true if everyone involved is highly liquidity or solvency constrained and has very good investment opportunities. In third world villages this is plausibly the case. In a result that should surprise no one, giving $36k to lower income Americans is now known not to be able to do that.

There is a fun argument in the comments between Noah Smith and Matt Darling, involving whether previous studies predicted there would be an employment effect. Noah’s position is that previous studies showed no effect. I notice that ‘sufficiently large cash transfers will cause people to work less’ is so obvious an implication that it never occured to me it could be otherwise unless this enabled lots of new investment.

John Arnold: Consensus among academics is that results of the OpenResearch UBI study were between mixed and disappointing. Yet most articles in the popular press (Forbes, Bloomberg, Vox, NPR, Quartz) characterize the results in a positive tone and ignore or bury the null/negative results.

Other outlets that have written extensively about UBI (NYT, WaPo) have ignored the story. Would they have covered it had the results been more positive? Coincidentally, a smaller, narrower UBI study was also released today that did have positive results (27% reduction in ER visits). WaPo covered that one.

This is a prime example of how much bias creeps into if and how a study is reported.

I will give a shout out to @WIRED’s coverage of the study, which I found to be an accurate and balanced description of the findings.

The NPR write-up focused on Sam Altman’s funding of the study, and on heartwarming anecdotes about individuals. It was indeed quite bad, attempting to put a positive spin on things.

The Bloomberg write-up from Sarah Holder and Shirin Ghaffary is entitled ‘Sam Altman-Backed Group Completes Largest US Study on Basic Income’ and it says up top ‘it found increased flexibility and autonomy for recipients.’ That the big takeaway is that the dollars provided ‘flexibility.’ This article too is clearly desperate to put on a positive spin on the results.

The Vox writeup from Oshan Jarow is entitled ‘AI isn’t a good argument for basic income,’ and repeatedly emphasizes the UBI is good but linking it to AI endangers the UBI project. Which is a weird angle. Then Oshan says that it shows benefits that have nothing to do with AI. What benefits? Well, the bad news is people worked a bit less, but the good news is this gave ‘the freedom to choose more leisure time’? And ‘interviews with participants paint a much brighter picture than the numbers’?

This felt very much like an ‘arguments as soldiers’ advocacy piece. Oshan Jarow clearly came in thinking UBI was definitely amazingly great and the question is how to get it to happen and what arguments are best to help with that. The actual study results were inconveniences to be spun. If you have the best study ever on UBI and you say ‘ignore the numbers and listen to the anecdotes’ then you are not winning.

(I couldn’t easily find the Quartz coverage).

Again, that does not mean UBI is a bad idea. I don’t think this study showed that. These still seem like rather blatant attempts to spin the results here into something they are not.

Here’s a data point you can read either way:

Scott Santens: Personally, I think one of the more interesting findings from @sama’s unconditional basic income pilot is how spending on others (like friends and family and charities) increased by 25%. It’s encouraging to see how much more giving we are when we have greater ability to give.

It is good that spending on others increased 25%, but income over those three years increased by more than that, and they did not end the period substantially wealthier. So in percentage of income terms, spending did not go up. But in terms of percentage of reported spending, it did. As Lyman Stone notes there, there isn’t enough reported spending and reduced earning to account for the money, yet reported wealth did not seem to increase much (or debt decrease much).

Colin Fraser explains the debt as ‘they bought cars’ and such, quoting the paper, but I don’t think the magnitude there is high enough to explain this.

Ramez Naam: Yesterday, results from OpenAI’s basic income study came out, with disappointing results. $1,000 / month for 3 months had little impact on people’s lives.

My response to this: Let’s focus on *lowering the cost of livingfor people, particularly at the bottom of the income.

How? By taking three of the most expensive things in America [Housing, Healthcare, and Eduction] and removing restrictions on supply, while introducing price competition.

Ease housing permitting. Force price clarity & consistency in medicine. Embrace competition in education.

Ramez makes excellent suggestions, that would be excellent with or without UBI. I would also note that we limit the ability to access lower-quality (or simply lower-quantity in many cases like housing) goods, including goods that would have been fine or even excellent in the not-too-distant past, raising the cost of living. We could absolutely make someone’s $30k/year go a lot farther than it does today, and we should do that no matter how much cash we give them on top of it.

A key question for UBI is whether it should be a substitute for the existing social safety net, or whether it is proposed in addition to the current social safety net. Is this an additional redistributive transfer, or are we having our transfers take a different form?

Among others, Arnold Kling notes that our current redistributive system effectively imposes very high marginal tax rates on the poor, as earning more causes them to lose their benefits. He notes that if we replaced the current system with UBI, especially a UBI that was not adequate to live on by itself but was still substantial (e.g. he suggests $5k/year for a family of four) then that would instead incentivize more work.

I continue to see a strong argument for doing less of our existing mess of conditional transfers, often confusing in-kind transfers that lose a lot of the value, and instead spending that money on UBI (and adjusting tax rates accordingly, so that above a threshold the effects cancel out). Then you would decide whether that was too little or too much UBI, as a distinct discussion.

What this study does is look at the effects of more UBI spending on its own, which is different. I do think this made me more likely to support transfers that target families with young children, including the child tax credit, as money better spent than giving UBI to all adults. That could also be considered as a UBI given to children via parents.

Josh Schwartz: I am being pushed off my position supporting UBI by the results of scientific study. It is a blow to the ego but I feel like if I don’t model the ability to respond to evidence, I can’t credibly teach that skill!

Peter Meijer: I was initially open to some form of UBI as a means of streamlining an administratively-bloated welfare system to increase benefits at lower cost to taxpayers, but several high quality studies have thoroughly undermined any argument for UBI.

Post from Eliezer Yudkowsky explaining why you are only as rich as your access to the least available vital resource. Having lots of Nice Things and needs met does not matter if one is missing, here air to breathe.

The pattern does seem to be that something ends up being scarce and expensive and considered vital, and that we require more and more things in ways that ensure people have to worry about not making ends meet.

Robin Hanson: “What would it be like for people to not be poor? I reply: You wouldn’t see people working 60-hour weeks, at jobs where they have to smile and bear it when their bosses abuse them.”

I doubt this. Status competition might induce many to do this, no matter how rich everyone is.

That is, it just might not be possible for everyone to be rich in status, and people may put in great efforts to increase their status, regardless of how rich they are in other ways.

Perhaps you’d say, it would look like no one working at those jobs in order to get the money. People would doubtless still do such work in the ‘rockstar’ style professions, the high stakes status competitions and places where everyone wants in on the action. But you would still have the option to opt out. Most people value status, but most people do not value status enough to work horrible 60-hour weeks purely for status.

We are looking into UBI in case conditions change. But then conditions will change.

James Miller: You can’t extrapolate from how UBI works when given to poor people today with how it would work in the future on people who today are middle class but in the future have been made unemployable by AI and robotics.

Sharmake Farah: What I’d say given the UBI results is that it only really makes sense for people who are essentially unemployable, as they spend it on leisure.

Which does suggest that it’s useful for it’s original purpose, but not for the other purposes it got added into.

Quite so. If this type of future does indeed come to pass, where large groups of people become ZMP (zero marginal product) workers without jobs, then everything is different.

If we give UBI to the poor now, we want to help their lives be better now and to consume more and also we want them to invest in becoming more productive.

In a world where those people cannot gainfully work, then work is a cost, not a benefit. UBI would hit very differently. A study like this tells us little about that world.

I strongly believe we should continue to study schemes to Give People Money in various ways, especially over long periods of time, and seeing what happens to people when their resources and incentives change. We will learn a lot. Thanks again for past-Altman for funding this study, and for all those involved for making it happen.