Enlarge / Scientists have observed wound care and selective amputation in Florida carpenter ants.

Florida carpenter ants (Camponotus floridanus) selectively treat the wounded limbs of their fellow ants, according to a new paper published in the journal Current Biology. Depending on the location of the injury, the ants either lick the wounds to clean them or chew off the affected limb to keep infection from spreading. The treatment is surprisingly effective, with survival rates of around 90–95 percent for amputee ants.

“When we’re talking about amputation behavior, this is literally the only case in which a sophisticated and systematic amputation of an individual by another member of its species occurs in the animal kingdom,” said co-author Erik Frank, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Würzburg in Germany. “The fact that the ants are able to diagnose a wound, see if it’s infected or sterile, and treat it accordingly over long periods of time by other individuals—the only medical system that can rival that would be the human one.”

Frank has been studying various species of ants for many years. Late last year, he co-authored a paper detailing how Matabele ants (Megaponera analis) south of the Sahara can tell if an injured comrade’s wound is infected or not, thanks to chemical changes in the hydrocarbon profile of the ant cuticle when a wound gets infected. These ants only eat termites, but termites have powerful jaws and use them to defend against predators, so there is a high risk of injury to hunting ants.

If an infected wound is identified, the ants then treat said wound with antibiotics produced by a special gland on the side of the thorax (the metapleural gland). Those secretions are made of some 112 components, half of which have antimicrobial properties. Frank et al.’s experiments showed that applying these secretions reduced the mortality rate of injured ants by 90 percent, and future research could lead to the discovery of new antibiotics suitable for treating humans. (This work was featured in an episode of a recent Netflix nature documentary, Life on Our Planet.)

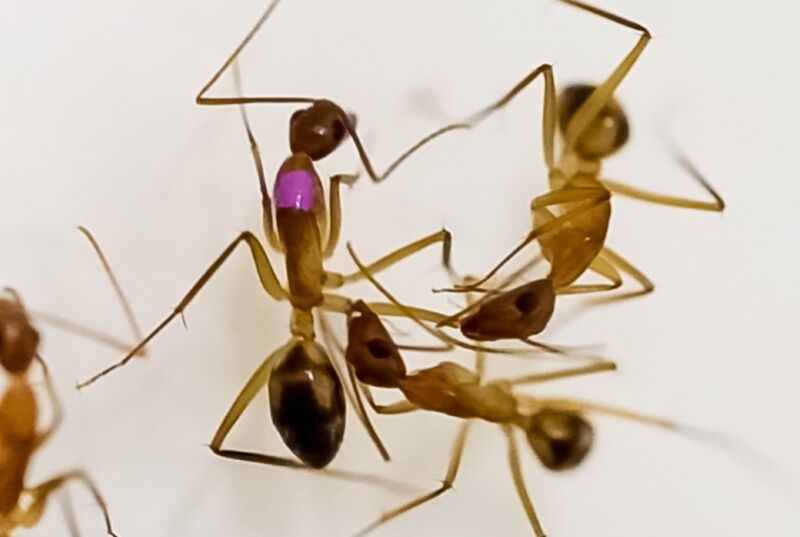

Amputation in Camponotus maculatus. Credit: Danny Buffat.

Those findings caused Frank to ponder if the Matabele ant is unique in its ability to detect and treat infected wounds, so he turned his attention to the Florida carpenter ant. These reddish-brown ants nest in rotting wood and can be fiercely territorial, defending their homes from rival ant colonies. That combat comes with a high risk of injury. Florida carpenter ants lack a metapleural gland, however, so Frank et al. wondered how this species treats injured comrades. They conducted a series of experiments to find out.

Frank et al. drew their subjects from colonies of lab-raised ants (produced by queens collected during 2017 fieldwork in Florida), and ants targeted for injury were color-tagged with acrylic paint two days before each experiment. Selective injuries to tiny (ankle-like) tibias and femurs (thighs) were made with sterile Dowel-scissors, and cultivated strains of P. aeruginosa were used to infect some of those wounds, while others were left uninfected as a control. The team captured the subsequent treatment behavior of the other ants on video and subsequently analyzed that footage. They also took CT scans of the ants’ legs to learn more about the anatomical structure.