Follow the crabs —

We’ve known about deep ocean vents for a while, but it’s still hard to find them.

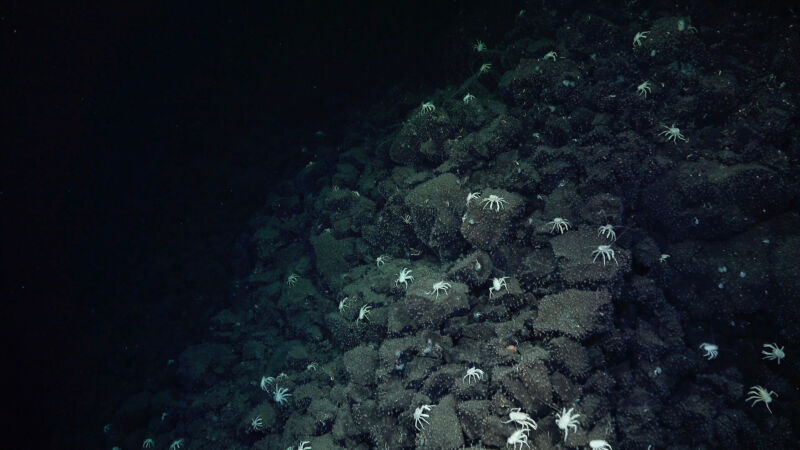

Enlarge / “Leading us like breadcrumbs…” A trail of squat lobsters helped researchers locate previously unknown hydrothermal vents. The hydrothermal vents create chemosynthetic ecosystems, so in areas that are mostly barren of life, the appearance of larger animals can be an indicator of vents nearby.

Spectacular scenery, from lush rainforests to towering mountain ranges, dots the surface of our planet. But some of Earth’s most iconic landmarks––ones that may harbor clues to the origin of life on Earth and possibly elsewhere––lay hidden at the bottom of the ocean. Scientists recently found one such treasure in Ecuadorian waters: a submerged mini Yellowstone called Sendero del Cangrejo.

This hazy alien realm simmers in the deep sea in an area called the Western Galápagos Spreading Center––an underwater mountain range where tectonic plates are slowly moving away from each other. Magma wells up from Earth’s mantle here to create new oceanic crust in a process that created the Galápagos Islands and smaller underwater features, like hydrothermal vents. These vents, which pump heated, mineral-rich water into the ocean in billowing plumes, may offer clues to the origin of life on Earth. Studying Earth’s hydrothermal vents could also offer a gateway to finding life, or at least its building blocks, on other worlds.

The newly discovered Sendero del Cangrejo contains a chain of hydrothermal vents that spans nearly two football fields. It hosts hot springs and geyser chimneys that support an array of creatures, from giant, spaghetti-like tube worms to alabaster Galatheid crabs.

The crabs, also known as squat lobsters, helped guide researchers to Sendero del Cangrejo. Ecuadorian observers chose the site’s name, which translates to “Trail of the Crabs,” in their honor.

“It did feel like the squat lobsters were leading us like breadcrumbs, like we were Hansel and Gretel, to the actual vent site,” said Hayley Drennon, a senior research assistant at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, who participated in the expedition.

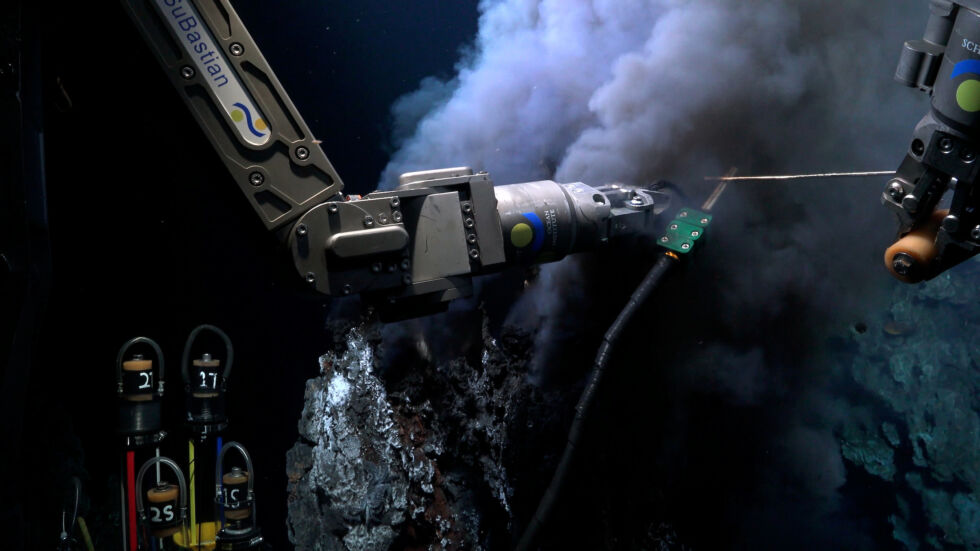

Enlarge / The Iguanas Vent Field, where the team did some sampling.

The joint American and Ecuadorian research team set sail aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s Falkor (too) research vessel in mid-August in search of new hydrothermal vents. They did some mapping and sampling on the way to their target location, about 300 miles off the west coast of the Galápagos.

The team used a ‘Tow-Yo’ technique to gather and transmit real-time data to the crew aboard the ship. “We lowered sensors attached to a long wire to the seafloor, and then towed the wire up and down like a yo-yo,” explained Roxanne Beinart, an associate professor at the University of Rhode Island and the expedition’s chief scientist. “This process allowed us to monitor changes in temperature, water clarity, and chemical composition to help pinpoint potential hydrothermal vent locations.”

When they reached a region that seemed promising, they deployed the remotely operated vehicle SuBastian for a better look. Less than 24 hours later, the team began seeing more and more Galatheid crabs, which they followed until they found the vents.

The crabs were particularly useful guides since the vent fluids there are clear, unlike “black smokers” that create easy-to-see plumes. SuBastian explored the area for about 43 hours straight in the robot’s longest dive to date.

But the true discovery process spanned decades. Researchers have known for nearly 20 years that the area was likely home to hydrothermal activity thanks to chemical signals measured in 2005. About a decade later, teams ventured out again and collected animal samples. Now, due to the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s recent expedition, scientists have the most comprehensive data set ever for this location. It includes chemical, geological, and biological data, along with the first high-temperature water samples.

“It’s not uncommon for an actual discovery like this to take decades,” said Jill McDermott, an associate professor at Lehigh University and the expedition’s co-chief scientist. “The ocean is a big place, and the locations are very remote, so it takes a lot of time and logistics to get out to them.” The team will continue their research onshore to help us understand how hydrothermal vents influence our planet.

Genesis from hell?

Sendero del Cangrejo may compare to a small-scale Yellowstone in some ways, but it’s no tourist destination. It’s pitch-black since sunlight can’t reach the deep ocean floor. The crushing weight of a mile of water presses down from overhead. And the vents are hot and toxic. Some of them clocked in at 290º C (550º F)—nearly hot enough to melt lead.

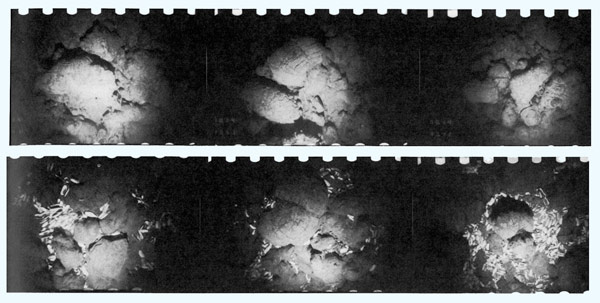

Before scientists discovered hydrothermal vents in 1977, they assumed such extreme conditions would preclude the possibility of life. Yet that trailblazing team saw multiple species thriving, including white clams that guided them to the vents the same way the Galatheid crabs led the modern researchers to Sendero del Cangrejo.

A series of seafloor photos shows the sudden appearance of live white clams that led scientists to find hydrothermal vents for the first time.

Before the 1977 find, no one knew life could survive in such a hostile place. Now, scientists know there are microbes called thermophiles that can only live in high temperatures (up to about 120º C, or 250º F).

Bacteria that surround hydrothermal vents don’t eat other organisms or create energy from sunlight like plants do. Instead, they produce energy using chemicals like methane or hydrogen sulfide that emanate from the vents. This process, called chemosynthesis, was first identified through the characterization of organisms discovered at these vents. Chemosynthetic bacteria are the backbone of hydrothermal vent ecosystems, serving as a nutrition source for higher organisms.

Some researchers suggest life on Earth may have originated near hydrothermal vents due to their unique chemical and energy-rich conditions. While the proposal remains unproven, the discovery of chemosynthesis opened our eyes to new places that could host life.

The possibility of chemosynthetic creatures diminishes the significance of so-called habitable zones around stars, which describe the orbital distances between which surface water can remain liquid on a planet or moon. The habitable zone in our own Solar System extends from about Venus’ orbit out nearly to Mars’.

NASA’s Europa Clipper mission is set to launch late next year to determine whether there are places below the surface of Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, that could support life. It’s a lot colder out there, well beyond our Solar System’s habitable zone, but scientists think Europa is internally heated. It experiences strong tidal forces from Jupiter’s gravity, which could create hydrothermal activity on the moon’s ocean floor.

Several other moons in our Solar System also host subsurface oceans and experience the same tidal heating that could potentially create habitable conditions. By exploring Earth’s hydrothermal vents, scientists could learn more about what to look for in similar environments elsewhere in our Solar System.

“The Ocean’s Multivitamin”

While hydrothermal vents are relatively new to science, they’re certainly not new to our planet. “Vents have been active since Earth’s oceans first formed,” McDermott said. “They’ve been present in our oceans for as long as we’ve had them, so about 3 billion years.”

During that time, they’ve likely transformed our planet’s chemistry and geology by cycling chemicals and minerals from Earth’s crust throughout the ocean.

“All living things on Earth need minerals and elements that they get from the crust,” said Peter Girguis, a professor at Harvard University, who participated in the expedition. “It’s no exaggeration to say that all life on earth is inextricably tied to the rocks upon which we live and the geological processes occurring deep inside the planet…it’s like the ocean’s multivitamin.”

But the full extent of the impact hydrothermal vents have on the planet remains unknown. In the nearly 50 years since hydrothermal vents were first discovered, scientists have uncovered hundreds more spread around the globe. Yet no one knows how many remain unidentified; there are likely thousands more vents hidden in the deep. Detailed studies, like those the expedition scientists are continuing onshore, could help us understand how hydrothermal activity influences the ocean.

Enlarge / ROV SuBastian takes water and chemical samples from a black smoker hydrothermal vent in the Iguanas Vent Field, Galapagos Islands.

The team’s immediate observations offer a good starting point for their continued scientific sleuthing.

“I actually expected to find denser animal populations in some places,” Beinart said.

McDermott thinks that could be linked to the composition of the vent fluids. “Several of the vents were clear—not very particle-rich,” she said. “They’re probably lower in minerals, but we’re not sure why.” Now, the team will measure different metal levels in water samples from the vent fluids to figure out why they’re low in minerals and whether that has influenced the animals the vents host.

Researchers are learning more about hydrothermal vents every day, but many mysteries remain, such as the eventual influence ocean acidification could have on vents. As they seek answers, they’re sure to find more questions and open up new avenues of scientific exploration.

Ashley writes about space as a contractor for NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center by day and freelances as an environmental writer. She holds a master’s degree in space studies from the University of North Dakota and is finishing a master’s in science writing through The Johns Hopkins University. She writes most of her articles with one of her toddlers on her lap.