Evolving views on food are challenging traditional diets — and not just for humans. Innovative dining options are also being added to the menus of our pets.

Startups have proposed numerous new ways to satiate their appetites. The UK’s Bella and Duke, for instance, caters to animals on raw diets, while Sweden’s Buddy Pet Foods serves natural dry food, and Portugal’s Barkyn personalises their grub.

If none of those excites their palates, our furry friends could try a more avant-garde delicacy: insects.

That’s what’s cooking in the kitchen of FlyFeed, an Estonia-based startup. The company has developed an automated farming system that turns fly larvae into animal feed.

“It’s challenging for humans, but a no-brainer for animals.

Arseniy Olkhovskiy, who founded FlyFeed in 2021, said the concept emerged from research into malnutrition. He concluded that insect farming can provide an affordable and sustainable solution to protein shortages. But he plans to feed animals before approaching humans.

“It’s challenging in human food right now, because people don’t really want to eat something connected to insects — but it’s a no-brainer in animal feed,” Olkhovskiy told TNW.

The 24-year-old rattles through a lengthy list of benefits of farming insects: they’re fed reprocessed waste that would otherwise rot in dumps; they grow up to 100 times faster than conventional animal food sources; they’re rich in high-quality nutrients; their production costs are minimal; and they require far fewer environmental resources than traditional agriculture.

Olkhovskiy promises they’re also highly palatable for pets. He says that his own cat is a fan of the flavours.

FlyFeed is not the first startup to turn insects into pet food. Ÿnsect in France has spent over a decade producing ingredients from mealworms, while Jiminy’s in the USA processes protein from crickets. FlyFeed uses another insect: black soldier flies.

This species has several attractions. The larvae can convert organic waste into edible protein for animal consumption and fertiliser. They’re also suitable for wet food, high in various nutrients, don’t transfer diseases, and have a fast growth rate.

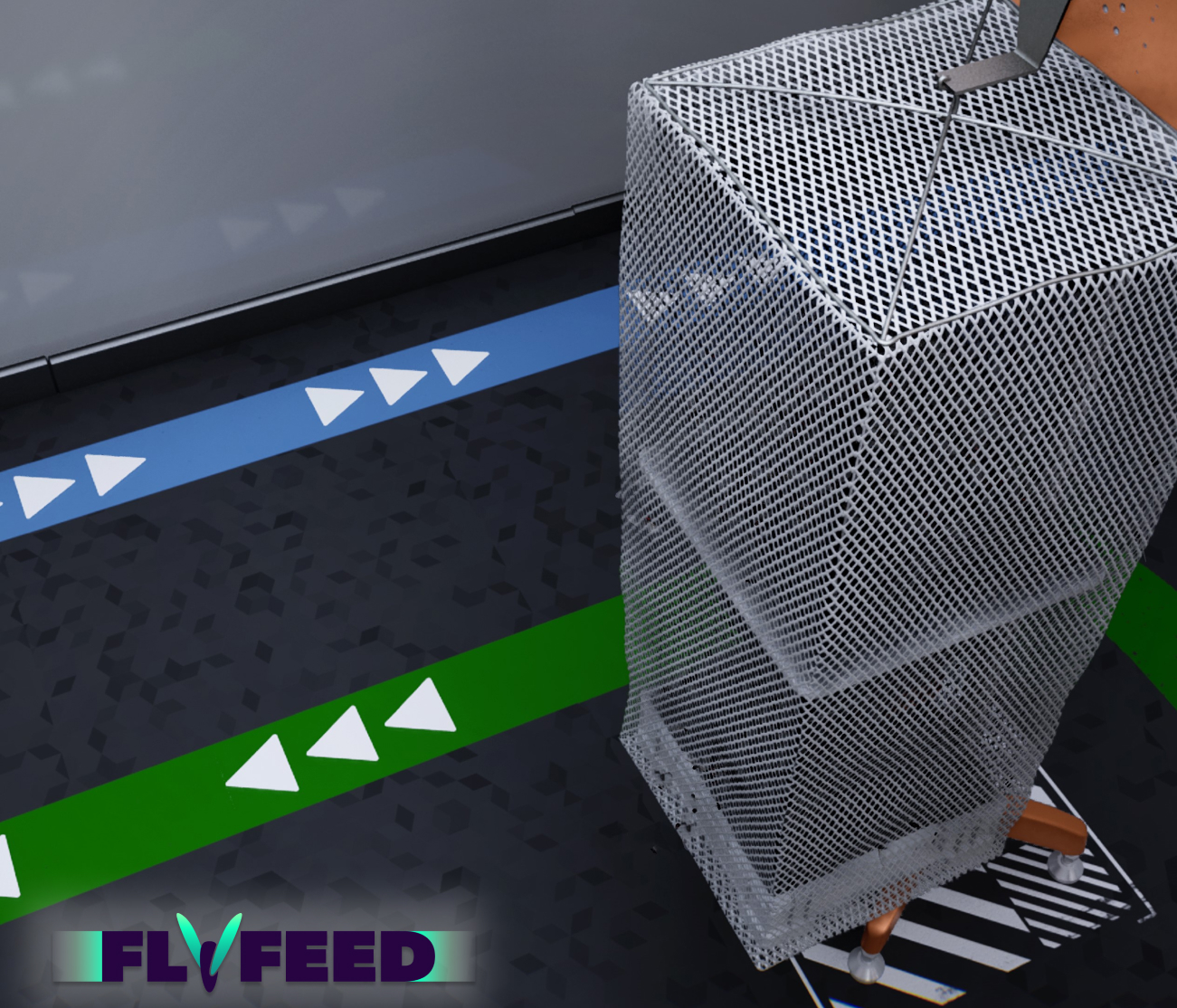

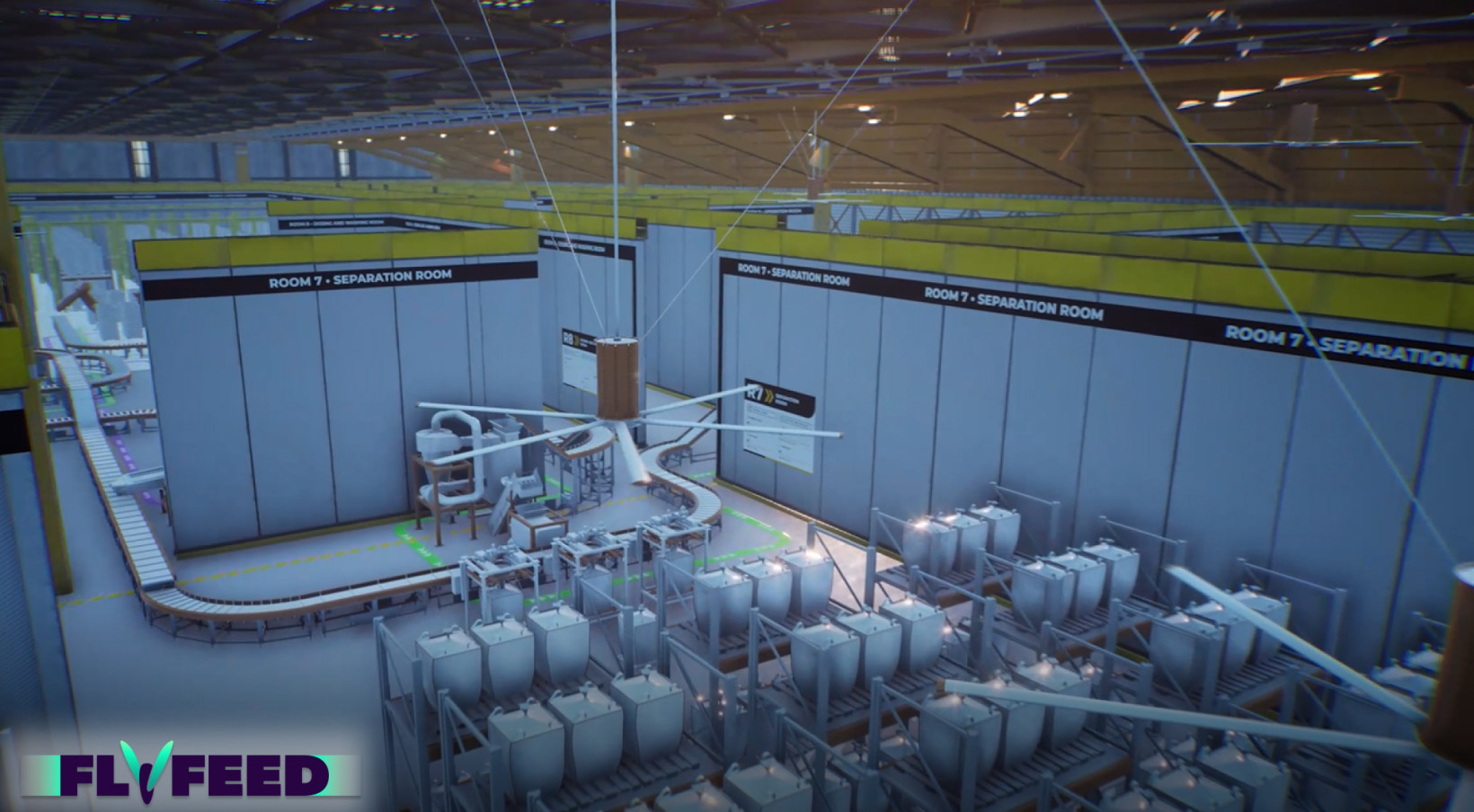

The insects will be reared on agricultural leftovers in vertically-stack crates, which reportedly require 100 times less space than soybean or livestock farming. The facility will also harness data-driven climate control to optimise conditions, and computer vision to monitor the larvae development.

Protein from the farm will be incorporated into comestibles. FlyFeed plans to deliver the first commercial batch of the product next year. Annually, the company aims to convert 40,000 tonnes of waste into 17,500 tonnes of insect products. The output will be split between proteins, fats, and fertilisers.

If all goes well, the early produce will provide a stepping stone to human consumption.

“First, we need to scale it,” said Olkhovskiy. “We need to make it cheaper, we need to make it of standardised quality, and we need to also bring it to markets where people actually need it.”

According to Olkhovskiy, other insect farming startups have struggled to market their food to humans. He’s chosen to instead focus on the operational and technological challenges. Once they’ve been overcome, Olkhovskiy plans to distribute the produce in countries where malnutrition is most critical. He expects to drive adoption through a low price point. While a kilo of protein from cheap chicken broilers goes for 4$, he says, a kilo of FlyFeed protein costs under 2$.

In Europe, however, the low prices are yet to create demand. According to a 2020 EU report, only 10% of Europeans are willing to swap meat for insects.

There are, however, signs that attitudes could change. A study published last December found people were more open to eating insects after learning about the environmental benefits.

Regulators are also starting to embrace the possibilities. In January, the EU approved the sale of house crickets and larvae for human consumption.

Still, it seems unlikely that we’ll all be eating flies in the near future. But perhaps our pets can convince us to give them a try.